Shaping Migration Discourse: A Text Analysis of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Speeches

-

Author(s):Rakovics, ZsófiaBoda, ZsuzsannaPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. , No. online first, 2025, pp. 1-16DOI: 10.54667/ceemr.2025.22Received:

14 March 2024

Accepted:25 July 2025

Published:31 October 2025

Views: 774

Migration policies have been a highly contested issue in Hungary, with political actors playing a pivotal role in shaping public opinion. This study examines the discourse on migration in the 1,421 English-language speeches of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán from January 2014 to December 2023. The research aims to enhance the understanding of migration-related rhetoric in political communication by employing natural language processing and quantitative text analysis techniques. Grounded in a theoretical framework of political discourse and migration narratives, the study explores shifts in the relative frequency and temporal patterns of key migration-related terms. Specifically, it analyses the usage of the terms ‘refugee’, ‘immigrant’, ‘migrant’, ‘migration’ and ‘immigration’, comparing their prevalence in speeches delivered within Hungary and on the international stage. The findings reveal significant shifts in Orbán’s migration rhetoric – notably, a decline in the use of the words refugee and immigrant in favour of migrant (which was not commonly used before). These results provide empirical evidence of discursive changes over time, contributing to a broader understanding of how political leaders strategically adapt their language to influence public perception. By contextualising these linguistic trends within Hungary’s sociopolitical landscape and in relation to previous research on political communication, this study offers valuable insights into the evolving role of migration discourse in political rhetoric. The findings also serve as a methodological contribution to the study of political speech analysis through computational text analytics.

Introduction

Many factors play a role in shaping the public opinion of the Hungarian population, including the values represented by the country’s politicians and government, which reach people through different communication channels and in different forms. The study of migration is a particularly good example with which to illustrate this. The research aims to contribute to the exploration of the way in which migration is discussed by analysing the speeches of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in English, available online, between January 2014 and December 2023.

Migration is constantly shaping our world, social interactions and political processes and, with the emergence of modern states, there is a growing political need in some countries and, to some extent, to limit migration and strengthen border protection. A wave of refugees on an unprecedented scale reached Hungary’s borders in 2015, challenging the country and Europe as a whole. The government’s decisions at the time included building a southern border fence and launching a National Consultation1 and Referendum on resettlement quotas and migrants (also known as the Quota Referendum2). It was during this period that Viktor Orbán’s narrative changed and his communication on refugees became a tool of his political strategy. This type of communication – centred around National Consultations, politicised information campaigns and the strategic use of the moral panic button or MPB – not only reshaped the media landscape and contributed to the rise of xenophobic attitudes among the Hungarian population but also significantly strained Hungary’s relationship with European institutions (Gerő and Sik 2020; Sik 2016a). The government’s persistent anti-Brussels rhetoric, framed as a defence of national sovereignty against external interference, fostered a hostile narrative that positioned the European Union as an adversarial force. This antagonistic stance not only deepened domestic polarisation by reinforcing in-group/out-group divisions but also challenged the normative and institutional foundations of Hungary’s EU membership (Gerő and Sik 2020; Sik 2016a).

Mapping and researching the messages in these speeches is particularly important not only for the reasons mentioned above but also because it defines the narrative of a country’s government, which can also influence the political attitudes of the population (Barna and Koltai 2019; Sik, Simonovits and Szeitl 2016). The consciously planned and thoroughly built narrative changed drastically for the second time when Ukrainian refugees arrived in Hungary due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. A differentiation between ‘real’ refugees and migrants was made by the Hungarian Prime Minister to counterpoint the previous, dominantly negative narrative on immigrants. Melegh’s article (2024) provides empirical evidence that the term ‘refugee’, which had previously been used less frequently, became more prevalent in articles by Hungarian media outlets during the Ukrainian crisis. The term ‘Ukraine’ was also added to these articles to facilitate understanding of the war-related events. The Prime Minister altered the discourse and demonstrated a capacity for agile adaptation in response to the prevailing circumstances.

The study examines the evolution of migration-related terms over time. Using basic descriptive tools associated with natural language processing and quantitative text analytics, the analysis provides an account of the migration-relevant aspects of Orbán’s speeches available online. We cover the social context of the issue of immigration and previous analyses of political communication related to it. We also describe how we conducted quantitative text analysis based on the theoretical framework. Further, we point out the changes in the relative frequency and temporal dynamics of words of particular relevance to migration. The keywords identified for the research include ‘refugee’, ‘immigrant’, ‘migrant’, ‘migration’ and ‘immigration’.3 Note that the Hungarian word for ‘migrant’ (‘migráns’) is a foreign-sounding loanword, unlike the more native-sounding ‘immigrant’ (‘bevándorló’) or refugee (‘menekült’). This lexical distinction has contributed to the stigmatisation of the term ‘migrant’ in public discourse, making it easier for governmental narratives to associate the term with threat, disorder or illegitimacy. In this context, Sik’s concept of the ‘moral panic button’ (Sik 2016a, b) is also highly relevant: it refers to a deliberate communication strategy that activates collective fear and anxiety by presenting migration as an existential threat. This mechanism plays a central role in Hungary’s political communication, enabling the government to mobilise support, suppress dissent and consolidate control by appealing to emotional rather than rational responses.

We believe that the results of the analysis can be used to identify at what point Viktor Orbán’s political communication changed, when the use of the words ‘refugee’ and ‘immigrant’ became less prominent and when the term ‘migrant’ became dominant in speeches. We also reflect on previous research findings relevant to the Hungarian case, as the results of the current research fit nicely with these.

Theoretical overview: Governmental and prime-ministerial narrative on immigration

In the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis, the 2010 parliamentary elections witnessed the victory of the Fidesz–KDNP party coalition, which secured a two-thirds majority. The nomenclature ‘Fidesz’ is an abbreviation for ‘Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance’. The political party known as Fidesz was established in 1988 under the name ‘Alliance of Young Democrats’. The Hungarian abbreviation KDNP signifies the Christian Democratic People’s Party. In 2010, the KDNP joined Fidesz in the Hungarian parliament, thereby becoming a constituent of the ruling party coalition. Since that time, the 2 parties have maintained their position in power. In this study, the term ‘Fidesz’ is preferred in place of ‘Fidesz–KDNP’ because Fidesz, with its leader, Viktor Orbán, plays a more significant role in shaping the political public sphere in Hungary than the KDNP. It is Fidesz and the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán who make decisions and, as the KDNP does not have a dominant political profile or agenda, the party does not participate in the national elections individually.

As a result of winning the national elections in 2010, the party coalition began governing without any significant opposition, transforming the country’s economic and social landscape. During his premiership, Viktor Orbán began to build his policies on ‘Hungarian values’, based on ‘millennial cultural dominance’ (Tölgyessy 2014: 643).4 The political transformation started a process of turning social groups and members of different generations against each other while, at the same time, the relationship between Europe and Hungary was weakening (Glied and Pap 2017). In order to counteract this, the former voiced themes and principles that the people of the country could be expected to agree with, including fear-mongering generated by immigration (Bocskor 2018).

As Endre Sik summarises in his studies (Sik 2016a, b), the 2015 National Consultation on Immigration and the way in which the result was announced5 was a moral panic button – a regular, even gradually reinforced message based on real or created threats. These messages appeared again and again on various media platforms, sometimes moving away from the issue of migration towards George Soros6 and Brussels. The success of these billboards was not only based on the fear of terrorism but also economic aspects (‘If you come to Hungary, don’t take away the jobs of Hungarians!’) and possible cultural effects (‘If you come to Hungary, you must respect our culture!’7). The main narrative that emerged from the referendum was blaming Brussels – and the liberal European elite – for their inability to defend their own borders.8 The other main narrative focused on threats, highlighting terrorism and violence9 (Glied and Pap 2017). Despite the government’s efforts and Billboard Campaign,10 the October 2016 referendum on the quota was invalid, as fewer than 50 per cent of voters participated. Nevertheless, Fidesz considered the event a political success, as 98 per cent of those who participated in the referendum voted against the quota.

The arrival of a significant wave of migrants at the southern border in 2015 was a Europe-wide challenge. From the beginning, the governing party prioritised communication about the problem, building an anti-immigrant narrative that culminated in the referendum on the resettlement quota in October 2016 (Glied and Pap 2017). In an interview with the Prime Minister in the summer of 2015, Viktor Orbán said that, if Western Europe could not protect the continent, Hungary would protect its own borders with a fence.11 With the current location of the Schengen southern border in Hungary, the Prime Minister painted the country as the guardian of the southern border of the whole of Europe, emphasising its historical identity as the bastion of Europe (Glied and Pap 2017: 140). The Prime Minister thus did not only physically create a fence separating Hungarian society from migrants; he also distinguished Hungarian national independence from European solidarity, as well as illiberal democracy from the functioning of European states – and religious tolerance from liberalism (Sata 2020: 72).

By the autumn of 2015, the government’s communication had taken a new direction and the focus had shifted to the impossibility of coexistence and the difficulties and dangers of a multicultural Europe, a message that was strongly underpinned by the terrorist attack in Paris in November 2015 (Glied and Pap 2017: 141). As argued by Kiss (2016: 45), the ‘controversial anti-immigration campaign, which consisted of two main elements: the National Consultation on Immigration and Terrorism and a connected Billboard Campaign (…) crucially shaped the perception of migration and asylum issues in Hungary’. According to Kiss (2016), this campaign not only framed migration as a security threat but also served as a central tool in constructing a politicised and emotionally charged public discourse. Through state-sponsored messaging and selective media representation, it contributed to the stigmatisation of asylum-seekers and reinforced a binary moral framework that positioned the government as the protector of national identity against an external, culturally incompatible threat (Kiss 2016).

The role of the governing party’s communication may have been significant in the fact that previously neutral words such as ‘migrant’ were attached to negative connotations and became hostile terms (Barna and Koltai 2019: 52). The result of such conscious communication was that refugees became confused with immigrants, illegal immigration with legal immigration, and migration with terrorism (Glied and Pap 2017: 144). In recent years, several studies have examined how Viktor Orbán’s speeches are followed up in the pro-government press, as well as the changing image of migrants and anti-immigration discourse in different media (Benczes and Ságvári 2022; Bernáth and Messing 2015; Bocskor 2018; Glied and Pap 2017). A constant element in these pieces of writing is how the word ‘refugee’, which expresses solidarity, is replaced by the term ‘migrant’, which was previously absent from the Hungarian language: a foreign word which, in itself, means foreigner (Benczes and Ságvári 2022). Benczes and Ságvári have also dealt with the differences in the meaning of the words ‘immigrant’, ‘migrant’ and ‘refugee’ – according to their hypothesis, ‘migrant’, the new term, has more diverse representations in the media than the other 2 words under study – a phenomenon we will also deal with in the research through the speeches. It is possible and worthwhile to draw parallels between the communication of the governing party media and the speeches of Viktor Orbán, since ‘an important characteristic of the Hungarian news media is that it is almost exclusively political discourse that determines both its language and its characteristic settings’ (Bernáth and Messing 2015: 7).

However, it is not only Hungarian researchers who have examined political discourses on migrants: for example, Sata (2020) found that Hungary stands out among countries for its extreme anti-immigration communication, despite not being a primary destination for the majority of immigrants but, rather, a sending country. Sata’s research analysed the speeches of Viktor Orbán from 2010 (when Fidesz came to power for the second time). The results show that, between 2010 and 2014, the main theme of the speeches was the economy, typically focusing on the country’s borders. Already by then, however, Christianity had emerged as a cardinal element of Hungarian identity, which Viktor Orbán’s speeches suggest is under threat from political and intellectual trends originating in Western Europe (Sata 2020: 62). This latter author draws attention to the differences in meaning already discussed in the literature that has been presented. In his experience, there were 5 times as many mentions of the words ‘migrant’ and ‘immigrant’ as of ‘refugee’. Due to this shift, immigrants are not portrayed as fallen and in need of help but as having come to the country for the expected economic benefits. Mention of the words ‘threat’, ‘protection’ and ‘security’ also increased several times in the period under review compared to previous years (2010–2014). Sata found that, since the change of government in 2010, the focus of the speeches has involved a consciously constructed crisis, to which parallels may be drawn with the moral panics and crisis communication discussed earlier (Gerő and Sik 2020). Another international collaboration (Korkut and Fazekas 2023) examined Hungary’s response to the Ukrainian refugee crisis through 2 key lenses: first, they considered how the country’s ties with Russia have influenced its stance on Ukraine, shaped in part by domestic political interests. Second, they contrasted Hungary’s handling of Ukrainian refugees with its earlier approach to migrants from the Middle East, highlighting shifts in its migration policies. Their study (Korkut and Fazekas 2023) also explored how political leadership and broader governance dynamics have influenced Hungary’s reception strategies and migration discourse. These international sources help to situate the current study within a broader scholarly context.

Research questions

The main research questions for the study are presented below based on the Introduction and Theoretical overview sections. To answer these questions, an analysis of the frequency of keywords related to the topic was carried out, complemented by a deeper interpretation of the texts, looking at the subtle differences in meaning. The study addresses the research question: How has the frequency of keywords relevant to migration changed in Viktor Orbán’s speeches in the examined 10-year period between 2014 and 2024? In other words: What dynamics can be observed in the use of words related to the topic? The analysis related to this question was conducted along the lines of the literature discussed in the Theoretical overview section, involving an examination of whether the anti-migrant narrative strengthened over time (Sata 2020) and whether the central messages were developed and reinforced by the government’s Billboard Campaign (Gerő and Sik 2020; Sik 2016a).

The hypothesis is that the frequency of the words under study has changed significantly over the period of analysis and that the messages that can be detected in government communication also appeared in the speeches. Based on the literature we reviewed, we hypothesised that the use of the term ‘migrant’ would predominate in the portrayal of immigrants compared to the more neutral terms ‘immigrant’ and ‘refugee’ and also that the deliberate shifts in the political narrative (for example, building up George Soros as an enemy, talking about Muslims as a threat and mentioning terrorism) could be detected in the frequency of the use of the corresponding keywords.

Methodological overview

Corpus and database

The analysis was conducted on the corpus of speeches of Viktor Orbán in English (either those delivered in English or official English translations), which is publicly available online. The corpus contains texts collected from the https://miniszterelnok.hu/en/ website and its archive(s). It includes speeches from January 2014 to December 2023 – a total of 1,421 individual texts. The database containing the text corpus also contains metadata – variables that record the circumstances under which the speech was given (for example, when, where and under what title Viktor Orbán gave the speech) – which data are also publicly available on the linked websites. Table 1 shows the distribution of the analysed speeches by year.

Table 1. Number and proportion (%) of prime-ministerial speeches by year

Methods applied

This section describes the methodological framework of the research. As discussed in the Corpus and database and Research questions sections, the analysis was conducted on the corpus of publicly available online speeches of Viktor Orbán. In the quantitative data analysis, we relied on pre-processing routines used in natural language processing and on quantitative text analysis methods based on word frequency and the use of bag-of-word models. The focus of the analysis was keywords relevant to the topic; the words ‘migration’, ‘immigration’, ‘migrant’, ‘immigrant’ and ‘refugee’ were awarded a prominent role in the analysis. We follow the methodological framework of a prior analysis in Hungarian (Boda and Rakovics 2022) but examine a more recent, 10-year period (2014–2024) of the English-language speeches of the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. In so doing, we contribute to the previous analysis by Boda and Rakovics and disseminate the results of a similar methodological approach for an updated period in the English language.

This section provides a methodological overview of the text analytical tools and text mining used for research, from the steps preceding the analysis to the procedures that were used. One of the key steps in text-mining analysis is the process of pre-processing texts, one of the aims of which is to establish the effectiveness of the analysis (Tikk 2007). One of the basic text-processing steps is tokenisation, whereby a document is broken down into a set of text units, called tokens, which are textual instances of a character sequence. The other basic pre-processing step is lemmatisation, which is used to find the normalised or dictionary form of words. Part-of-speech recognition is also a procedure commonly used to understand the grammatical role of each word in a sentence. An important tool in text preparation is the compilation of stop words – which do not carry information of value for analysis – such as conjunctions and fillers (Tikk 2007). The pre-processed text corpus was produced after, among other things, implementing the above procedures and contained already cleaned texts.

The toolbox of text quantitative analytics is rich, with a variety of approaches and methods to suit the research questions. One of the simplest approaches is based on the bag of words model, whereby the frequency of words in a corpus is examined without recording information on their position and order within the text (Tikk 2007). This type of approach can be useful in a research project that examines which words are prominent in the texts under study and how often they appear in them. We chose this approach, focusing the analysis on keywords related to the topic of migration. Based on theoretical considerations, we looked for words and phrases that typically occur when discussing the topic. By examining the observed frequencies of occurrence for each period we can, in a sense, trace the temporal dynamics of the appearance of words – and this is what we examined in the analysis.

To standardise and better compare word frequencies, the length of utterances was also taken into account in the analysis and relative frequencies were calculated by dividing the observed frequencies by the number of words. Differences in the frequencies of word use were also analysed using statistical tests. In principle, we relied on established quantitative data analysis procedures. When examining the average word frequency of different types of speech, independent sample t-tests were used to inspect the frequency of a selected keyword in 2 different types of speech. When studying the typical occurrence of the highlighted word pairs, paired sample t-tests were employed to analyse differences in meanings. Results were generally presented using bar and line graphs. Data pre-processing was performed in R and text analysis in SPSS.

Examining the weighted word frequencies of keywords is relevant when trying to explore the empirical patterns observed in the prime ministerial speeches but may have limitations. It is considered a somewhat quantitative approach that could be complemented with qualitative analysis in order to gain a deeper understanding of the matter. We deliberately applied quantitative text analysis and targeted quantitative investigations because the previous research analysing Viktor Orbán’s speeches from the perspective of migration focused more on the qualitative aspects of the topic. Therefore, the current analysis could be considered a valuable contribution, complementing the pre-existing methodological framework in the study of the topic of migration in the speeches of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Results

We first analysed the relative frequency of general keywords relevant to migration, such as ‘migration’, ‘immigration’, ‘migrant’, ‘immigrant’ and ‘refugee’, in the speeches of Viktor Orbán between January 2014 and December 2023. We then analysed the words that fall under the broader framework of the topic. The extended theme identified several keywords that were among those used in the National Consultations launched by the government and in the Billboard Campaigns, such as ‘Brussels’, ‘Soros’, ‘Hungary’, ‘Hungarian’, ‘homeland’, ‘faith’, ‘religion’, ‘religious’, ‘Catholic’, ‘Muslim’, ‘culture’ and ‘tradition’. The following words, which appear in the speeches and have a negative connotation in relation to immigrants were also included: ‘enemy’, ‘adversary’, ‘rival’, ‘violence’, ‘violent’, ‘threat’, ‘attack’, ‘terrorist’, ‘terrorism’, ‘danger’, and ‘dangerous’ (see Note 3 for a full list of the words that were analysed).

We examined the dynamics of the use of related terms in all online speeches available for a given period and the differences in average word frequencies, thus studying and interpreting the differences in political communication. The quantitative data analysis related to the research question is summarised in the following subsection.

Examining the word frequency of keywords

Differences in the use of the terms ‘migration’ and ‘immigration’ were tested using a paired sample t-test to see if there was a statistical difference in relative word frequencies across all the speeches in the given period. A significant (p < 0.001) difference (0.1 percentage points) was found when analysing the relative frequencies of the 2 keywords, with the word ‘migration’ (mean = 0.16 per cent, standard deviation = 0.37, maximum = 3.4 per cent) scoring higher than that of ‘immigration’ (mean = 0.06 per cent, standard deviation = 0.18, maximum = 2.0 per cent). The result is well-aligned with what has been reported in the theoretical literature, with Prime Minister Viktor Orbán preferring the use of the term ‘migration’ over ‘immigration’ in his speeches.

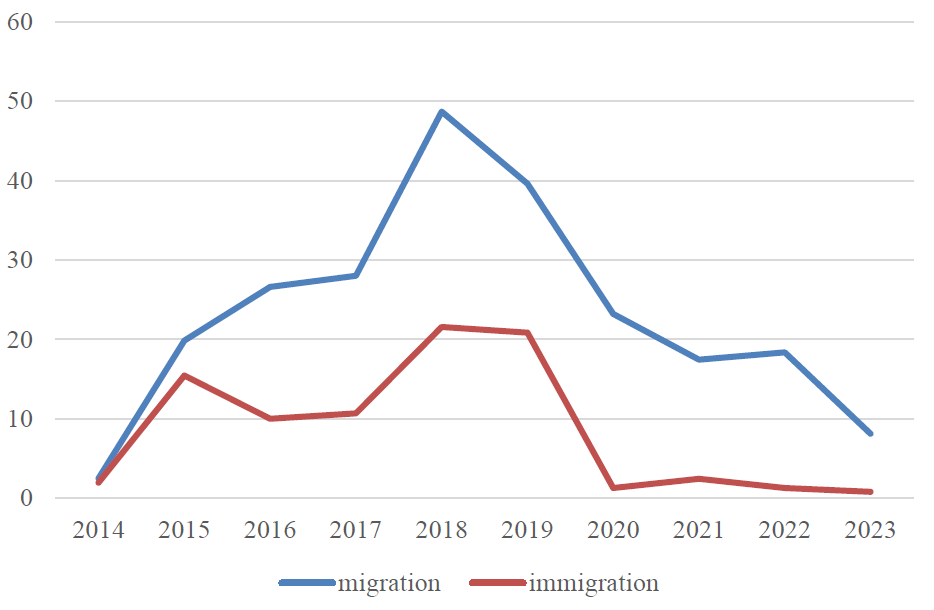

Plotting the results over time (Figure 1), while the weighted annual occurrence of ‘immigration’ and ‘migration’ were similar in 2015, following that date the weighted annual frequency of ‘migration’ became more dominant.

Figure 1. Weighted annual occurrence of the words ‘migration’ and ‘immigration’

The weighted annual frequencies started rising in 2016 and, thereafter, the term ‘migration’ was used more frequently than ever before in Viktor Orbán’s speeches – in 2017–2018 (27 and 28 times, respectively) – and reached its peak in 2018 (49). The trend then broke, with the weighted annual occurrence of ‘migration’ being 40 in 2019 and 23, 17, 18 and 1, in 2020–2023 respectively.

For the pairing ‘refugee’ and ‘migrant’, the t-test significance value (p < 0.001) showed a statistical difference (0.08 percentage points) in the mean relative word frequencies; the average occurrence of ‘migrant’ was 0.12 per cent (standard deviation = 0.26, maximum = 3.29), while that of ‘refugee’ was 0.04 per cent (standard deviation = 0.24, maximum = 6.25). For the pair ‘immigrant’ and ‘migrant’, the test was also significant (p < 0.001), with the observed difference (0.08 percentage points) in favour of the latter; the mean of the relative prevalence of the term ‘immigrant’ was 0.04 per cent (standard deviation = 0.15, maximum = 2.12) and, of the term ‘migrant’, 0.12 per cent (as detailed before). There was no significant difference when comparing the relative frequencies of the terms ‘refugee’ and ‘immigrant’ together.

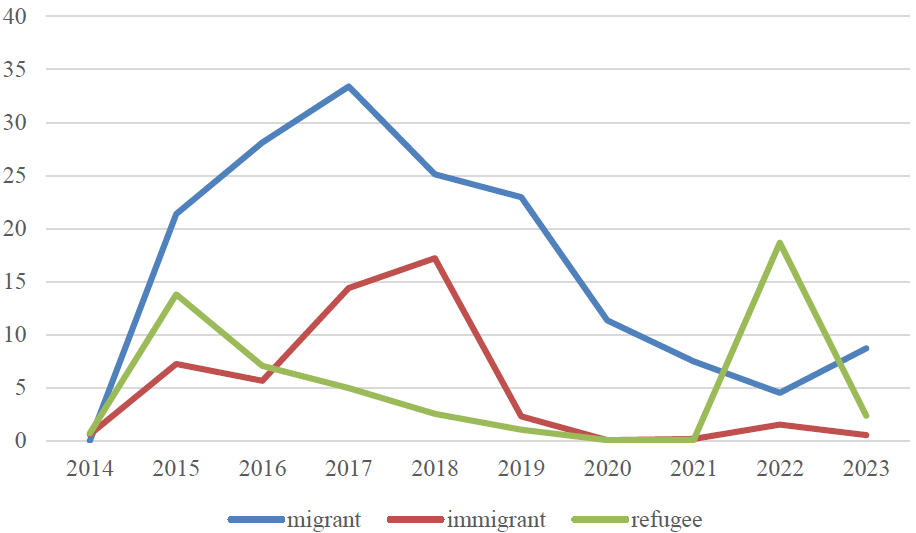

The results were plotted over time for the keywords ‘refugee’, ‘immigrant’ and ‘migrant’ and the same trend as above can be observed. By 2015, the use of the former 2 had significantly diminished, and the term ‘migrant’ had come to the fore. The weighted annual occurrences of these keywords by year are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Weighted annual occurrence of the words ‘migrant’, ‘immigrant’ and ‘refugee’

As expected, the weighted annual frequency of these words started to increase after 2014 – when the wave of refugees started – and the use of the term ‘refugee’ in 2015 was quite frequent (14 occurrences), before ‘migrant’ and ‘immigrant’ became more dominant. The term ‘refugee’ peaked in 2022 at the time of the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, when thousands of refugees arrived in Hungary from the neighbouring country. The phrase ‘migrant’ appeared in the speeches from 2015 onwards; the weighted occurrence was 21 and 28 in 2015 and 2016 respectively. The word ‘migrant’ had a maximum value of 33 in 2017, following which a decline was observed until 2022 (the values were 25, 23, 11, 7 and 5), and in 2023, ‘migrant’ again became more used and the annual weighted frequency increased to 9. The use of the word ‘immigrant’ reached its peak between 2017 and 2018 (14 and 17, respectively) and was then used less frequently.

These results fit nicely with those found in previous research and the literature cited in the Theoretical overview section reports a similar trend. All this clearly shows that, from 2016 onwards, Viktor Orbán favoured the use of the term ‘migrant’ in his speeches, except for the year 2022 – the Russian invasion of Ukraine – when ‘refugee’ was more dominant. In line with the results of previous research, we see the outcome of conscious strategic communication; the deliberate marginalisation of the empathetic words ‘refugee’ and the more neutral ‘immigrant’ and an increase in the use of the term ‘migrant’, in line with political strategy and evoking a preconditioned emotional charge. We also analysed the frequency and temporal dynamics of the words ‘Brussels’, ‘Soros’, ‘migration’ and ‘migrant’, which appear in National Consultations and Billboard Campaigns (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Weighted annual occurrence of the words ‘Brussels’, ‘Soros’, ‘migration’ and ‘migrant’

The term ‘Brussels’ is used in several of Viktor Orbán’s speeches to refer to the European Union in general; the weighted annual frequency of the word was 10 and 9 in 2014 and 2015 respectively. The local maximum occurred in 2016 with 32 mentions, then a decrease was observed: 29, 19, 21, 13 and 9 between 2017 and 2021. In 2022 – the year of the elections – use of the term ‘Brussels’ reached its maximum within the examined 10-year period with 36 mentions and, in 2023, 20. Reference to George Soros first appeared in 2016, then peaked in 2017 with a weighted occurrence of 14 while, in 2018, the observed value was 12. The year 2019 witnessed a local minimum (4) and from then onwards, the values were as follows: 9, 4, 1 and 1 between 2020 and 2023 respectively. Studying the series of ‘Brussels’ and ‘Soros’ together with ‘migrant’ and ‘migration’ revealed that the terms ‘Soros’ and ‘migrant’ co-occurred, especially between 2016 and 2018. Note that this was the period of the ‘Stop-Soros’ Billboard Campaign. Examining the co-occurrence of ‘Brussels’ and ‘migration’ shows periods of synchronisation – for example, between 2015 and 2017, 2019 and 2021 and 2022 and 2023.

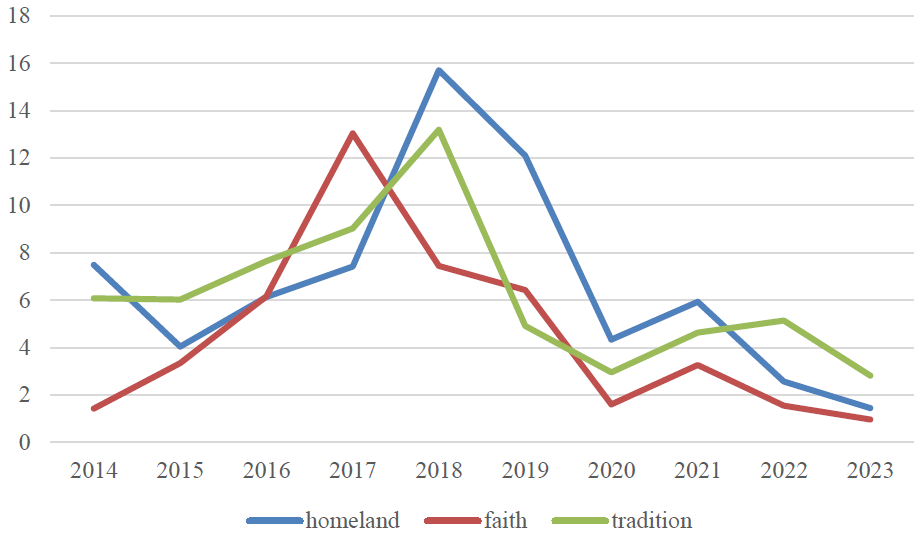

The words ‘homeland’, ‘faith’ and ‘tradition’ were among those typically used in the political campaigns of the Orbán government (the National Consultations and the Billboard Campaigns), so we studied them as well. Figure 4 shows the weighted annual frequency of these words.

Figure 4. Weighted annual occurrence of the words ‘homeland’, ‘faith’ and ‘tradition’

The annual weighted frequency of the term ‘homeland’ dropped from the value observed in 2014 (7) to 2015–2016 (4 and 6, respectively) but then, in 2017–2019, it was more frequent (7, 16 and 12) in the prime ministerial speeches, while between 2021 and 2023 it declined. The word ‘faith’ reached its peak in 2017 when the maximum of the weighted occurrence was 13; before and after that year, the values ranged between 1 and 7, with a slightly different dynamic: the years 2016, 2018 and 2019 saw higher weighted frequencies (6, 7 and 6 respectively), while 2014, 2015 and 2020–2023 saw lower ones. Use of the word ‘tradition’ increased between 2014 and 2018 (6, 6, 8, 9 and 13, respectively) and then dropped between 2019 and 2020 (5, 3), stagnating at around 4–5. Although ‘migration’ is not represented in this illustration, the peaks of the examined keywords ‘homeland’, ‘faith’ and ‘tradition’ were synchronised with the weighted annual occurrence of ‘migration’.

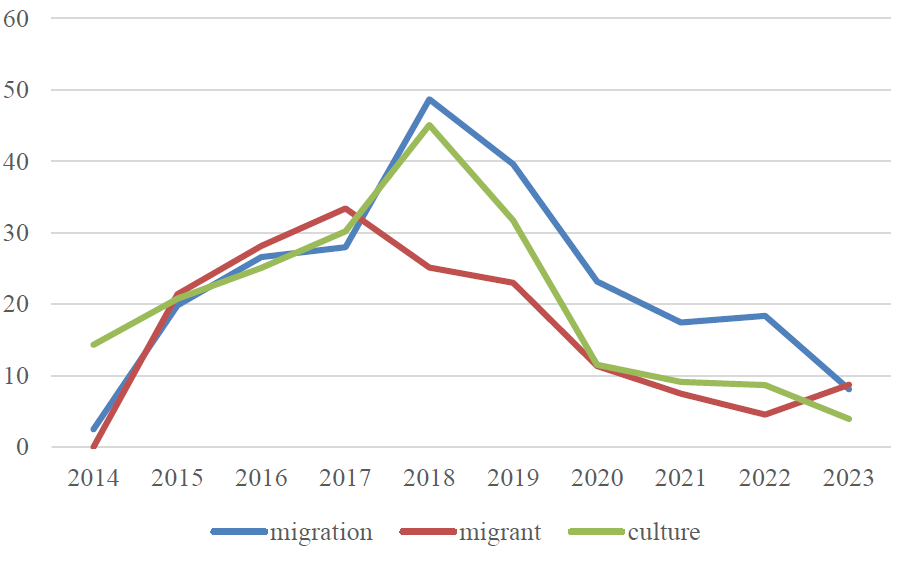

Figure 5. Weighted annual occurrence of the words ‘migration’, ‘migrant’ and ‘culture’

The following was true for the term ‘culture’ as well, which condensed a complex message. Therefore, Figure 5 demonstrates the co-occurrence of ‘migration’, ‘migrant’ and ‘culture’. The latter keyword was an integrated part of the billboard and political communication campaigns.

The word ‘culture’ was already associated with a relatively high weighted annual occurrence in 2014 (14) and then increased constantly until 2018 (21, 25, 30, then 45 mentions), respectively. The absolute maximum within the examined period was observed in 2018. Following that, the weighted annual frequency declined to 32 in 2019 and then to 11 in 2020. The values stagnated at 9 for 2021 and 2022. The latest observed weighted occurrence was 4 in 2023.

Figure 6. Weighted annual occurrence of the words ‘Hungary’, ‘Hungarian’, ‘migration’ and ‘migrant’

The terms ‘Hungary’ and ‘Hungarian’ were among those the most frequently used within the prime ministerial speeches. The study of the weighted annual occurrences of those was therefore essential. Figure 6 shows the results over time while also showcasing the temporal change in the use of the terms ‘migration’ and ‘migrant’.

Usage of the keywords ‘Hungary’ and ‘Hungarian’ were well-aligned; the increase started in 2014, the weighted annual frequencies were 208, 2022, 330, 378 and 368 for ‘Hungarian’ and 170, 190, 215, 287 and 333 for ‘Hungary’ between 2014 and 2018, respectively. Use of the word ‘Hungarian’ peaked in 2017 and of ‘Hungary’ in 2018. Viktor Orbán used these terms less frequently in the following year (2019), as the weighted annual occurrence for ‘Hungarian’ was 287 and for ‘Hungary’ 261. The decline started in 2018 and ended in 2021: the observed measures were 100 for ‘Hungarian’ and 93 for ‘Hungary’. The weighted annual occurrence of the word ‘Hungarian’ was almost always higher than for ‘Hungary’, with one exception: 2022, the year of a critical national election, which proved surprisingly successful for Viktor Orbán’s government. In 2022, the calculated measures were 163 and 137 in favour of ‘Hungary’. Year 2023 was observed to be similar to 2021, considering the computations of weighted annual occurrences. Although the volume of the keyword pairs ‘Hungary’ –‘Hungarian’ and ‘migration’–‘migrant’ was not comparable, over time we observed synchronicity in changes in the weighted annual frequencies.

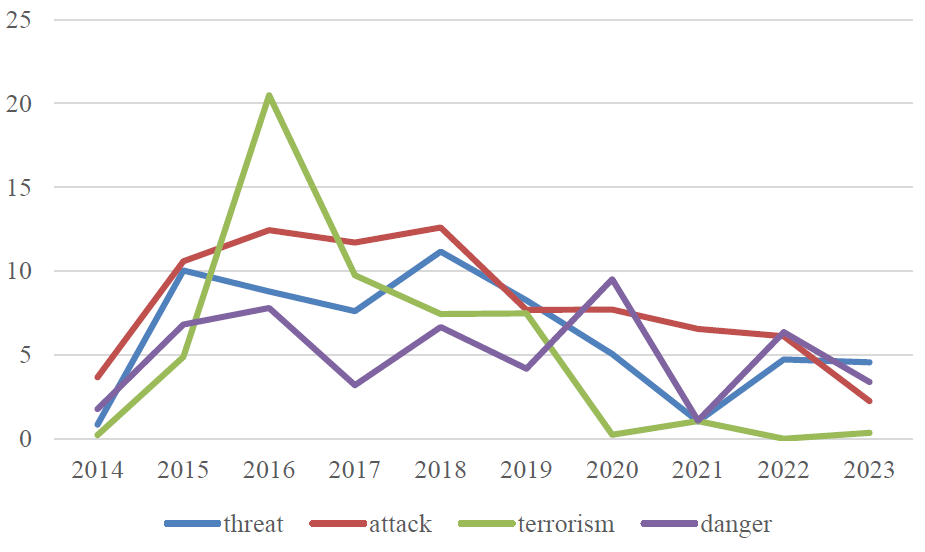

Several other keywords were associated with the topic of migration in the Prime Minister’s speeches. The study of the weighted annual frequencies of words like ‘threat’, ‘attack’, ‘terrorism’, ‘terrorist’, ‘danger’, ‘dangerous’, ‘violence’ and ‘violent’ may also contribute to the understanding of the political communication strategies of Viktor Orbán. Therefore, we also examined some of them and completed our analysis with the results. In Figure 7, the weighted annual frequency of selected terms (‘threat’, ‘attack’, ‘terrorism’, ‘danger’) is displayed.

Figure 7. Weighted annual occurrence of the words ‘threat’, ‘attack’, ‘terrorism’ and ‘danger’

In the examined 10-year period, the word ‘threat’ appeared first in 2014, although the weighted annual frequency was low (1 in 2015); it then increased to 10, then slightly decreased to 9 and 8 in 2016–2017. In 2018, it reached its maximum, 11 and then declined until 2021 (between 2019 and 2021, 8, 5 and 1, respectively). In 2022 and 2023, the annual weighted frequency stagnated at 5. The verb ‘attack’ started with a relatively low weighted occurrence in 2014, then rose to 11, 12, 12 and 13 between 2015 and 2018. From 2019 to 2023 it declined (8, 8, 7, 6 and 2). The word ‘terrorism’ appeared for the first time in 2015 when its weighted frequency was 5; by 2016, its use had increased drastically to 20. Following that peak in 2016, it dropped to 10, 7 and 7 between 2017 and 2019, after which it was used significantly less.

Discussion and conclusions

We analysed the speeches made by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán from the beginning of 2014 to the end of 2023 (a total of 1,421 individual speeches) that were available online at miniszterelnok.hu/en and its archive page(s).

To build the theoretical framework, we examined the development of immigration and xenophobia in Hungary (see, for example, Barna and Koltai 2019; Sik 2016a), the evolution of immigration policy under the Orbán government and previous analyses of the communications of the Prime Minister and the governing party on the issue of immigration (see Benczes and Ságvári 2022; Glied and Pap 2017; Sata 2020). Based on the theoretical framework defined for the research, we conducted a quantitative analysis using descriptive text analytical tools after applying pre-established pre-processing steps for natural language processing. The analysis was based on words that have featured prominently in previous research on migration, as well as in government policy communications and the migration narrative associated with Billboard Campaigns.

The research question addressed how the occurrence of keywords relevant to migration changed in Viktor Orbán’s speeches during the 10-year period between 2014 and 2024. In other words, what dynamics were observed in the use of words related to the topic? We used statistical tools to compare the relative frequencies of keywords. We also computed weighted annual occurrences of key terms to compare them over time in order to investigate possible differences in political communication strategies.

The results of the analysis confirm the conclusions of previous studies summarised in the Theoretical overview. In 2015, Viktor Orbán used the term ‘immigration’ relatively often in his speeches but, from then on, the use of the term ‘migration’ started to increase and, in the following years, exceeded the former and reached its maximum in 2018, along with ‘immigration’, which was less dominant in terms of usage but still peaked that year. A similar trend was observed from an examination of the words ‘refugee’, ‘immigrant’ and ‘migrant’: use of the term ‘migrant’ gained strength after 2015 and, while the mentions of the other 2 terms decreased, ‘migrant’ continued to be more frequently used than the other 2 combined. Other researchers have also found that the use of the word ‘migrant’ in political communication is a conscious choice intended to alienate the group and develop negative connotations (Benczes and Ságvári 2022). The mention of ‘Brussels’ and ‘Soros’ also spectacularly increased in speeches after 2015, which suggests that Viktor Orbán’s speeches were a traceable expression of the government’s communications, which were critical of Brussels and George Soros. Analysis of key terms like ‘threat’, ‘attack’, ‘terrorism’ and ‘danger’ confirmed the hypothesis –supported by the literature we have presented – that, over time, the negative image of immigrants in Viktor Orbán’s speeches became reinforced in line with the government’s anti-migrant narrative. It can also be argued that he included in his speeches the same themes and keywords that were raised in the government’s Billboard Campaigns.

This work contributes to previous research that has analysed Viktor Orbán’s speeches from the perspective of migration – much of it more qualitatively focused – and complements it with a quantitative text analysis of all Orbán’s English-language speeches delivered between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2023 that are available online. While grounded in existing analyses focused on Hungary, this study makes a distinct contribution through its use of a large, original dataset of Viktor Orbán’s English-language speeches and the application of quantitative text analysis. To our knowledge, this is the first study to apply this methodology in this context, thereby offering fresh insights into the international dimension of Hungarian political communication.

Notes

- Note that National Consultations in Hungary are government-initiated survey questionnaires sent by mail to all Hungarian citizens with a registered address. These surveys typically ask for opinions on politically sensitive topics – such as immigration, EU relations or economic policy – and are framed in a way that reflects the government’s stance. While presented as tools for public input, they are widely criticised for being biased, leading and used more as instruments of political mobilisation and legitimisation than genuine democratic consultation.

- The Quota Referendum in Hungary, held on 2 October 2016, was a national vote organised by the Hungarian government to oppose the European Union’s plan to redistribute asylum-seekers among member states through mandatory quotas.

- Full list of keywords selected and used for the analysis: adversary; attack; Brussels; Catholic; culture; danger; dangerous; enemy; faith; homeland; Hungarian; Hungary; immigrant; immigration; migrant; migration; Muslim; refugee; religion; religious; rival; Soros; terrorism; terrorist; threat; tradition; violence; violent.

- The phrase ‘millennial cultural dominance’ as used by Tölgyessy (2014: 643) refers to the long-standing, historically rooted influence of a particular cultural or ideological framework that has shaped a society – specifically Hungary – for many centuries (i.e., over a ‘millennium’).

- ‘The people have decided: the country must be defended’ – Viktor Orbán’s speech before the agenda in Parliament on 21 September 2015.

- ‘Don’t let Soros have the last laugh’ – government Billboard Campaign, 2017.

- Quotes from the government Billboard Campaign.

- ‘Let’s send a message to Brussels so they understand’ – billboards in 2016.

- Billboards starting with ‘Did you know?’. For example, ‘Did you know? Since the beginning of the immigration crisis, the number of incidences of harassment against women in Europe has skyrocketed’; ‘Did you know? More than 300 people have died in terrorist attacks in Europe since the beginning of the immigration crisis’.

- Billboard Campaigns in Hungary refer to large-scale, state-funded public messaging efforts primarily conducted through posters and billboards placed across the country. These campaigns have been a central communication tool of the Orbán government – especially since the 2015 migration crisis – and are typically tied to politically charged themes.

- ‘If we don’t protect our borders, tens of millions of people will come to Europe again and again’, the Prime Minister said on Kossuth Radio’s 180 Minutes programme on Friday. The Prime Minister said that there is a serious difference of opinion between the EU and Hungary, because most EU leaders believe that everyone should be allowed in but, if we let everyone in, Europe will be finished’ (https://hirado.hu/2015/09/04/hallgassa-itt-eloben-a-miniszterelnoki-inte..., accessed 4 September 2025).

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID ID

Zsófia Rakovics  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9903-9348

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9903-9348

References

Barna I., Koltai J. (2019). Attitude Changes Towards Immigrants in the Turbulent Years of the ‘Migrant Crisis’ and Anti-Immigrant Campaign in Hungary. Intersections – East European Journal of Society and Politics 5(1): 48–70.

Benczes R., Ságvári B. (2022). Migrants Are Not Welcome. Metaphorical Framing of Fled People in Hungarian Online Media, 2015–2018. Journal of Language and Politics 21(3): 413–434.

Bernáth G., Messing V. (2015). Bedarálva. A menekültekkel kapcsolatos kormányzati kampány és a tőle független megszólalás terepei. Médiakutató 16(4): 7–17.

Bocskor Á. (2018). Anti-Immigration Discourses in Hungary During the ‘Crisis’ Year: The Orbán Government’s ‘National Consultation’ Campaign of 2015. Sociology 52(3): 551–568.

Boda Z., Rakovics Z. (2022). Orbán Viktor 2010 és 2020 közötti beszédeinek elemzése. Szociológiai Szemle 32(4): 46–69.

Gerő M., Sik E. (2020). The Moral Panic Button 1: Construction and consequences, in: E.M. Goździak, I. Main, B. Suter (eds) Europe and the Refugee Response, pp. 39–58. London: Routledge.

Glied V., Pap N. (2017). The ‘Christian Fortress of Hungary’ – The Anatomy of the Migration Crisis in Hungary, in: B. Góralczyk (ed.) Yearbook of Polish European Studies, pp. 133–150. Warsaw: Centre for European Regional and Local Studies, University of Warsaw.

Kiss E. (2016). ‘The Hungarians Have Decided: They Do Not Want Illegal Migrants’. Media Representation of the Hungarian Governmental Anti-Immigration Campaign. Acta Humana–Emberi Jogi Közlemények 4(6): 45–77.

Korkut U., Fazekas R. (2023). The Ruptures and Continuities in Hungary’s Reception Policy: The Ukrainian Refugee Crisis. Central and Eastern European Migration Review 12(1): 13–29.

Melegh A. (2024). The Consolidation of Polarization. Hungarian Discourses on Migration. Corvinus Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 15(3): 75–104.

Sata R. (2020). Fencing in the Boundaries of the Community: Migration, Nationalism and Populism in Hungary, in: R. Sata, J. Roose, I.P. Karolewski (eds) Migration and Border-Making. Reshaping Policies and Identities, pp. 52–76. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Sik E. (2016a). Egy hungarikum: a morálispánik-gomb. Mozgó Világ 42(10): 67–80.

Sik E. (2016b). The Socio-Demographic Basis of Xenophobia in Contemporary Hungary, in: B. Simonovits (ed.) The Social Aspects of the 2015 Migration Crisis in Hungary, pp. 41–48. Budapest: Tárki Social Research Institute.

Sik E., Simonovits B., Szeitl B. (2016). Az idegenellenesség alakulása és a bevándorlással kapcsolatos félelmek Magyarországon és a visegrádi országokban. REGIO 24(2): 81–108.

Tikk D. (2007). Szövegbányászat. Budapest: Typotex Kiadó, 20–58.

Tölgyessy P. (2014). Válság idején teremtett mozdíthatatlanság, in: T. Kolosi, I.G. Tóth (eds) Társadalmi Riport 2014, pp. 636–653. Budapest: Tárki.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.