(Un)Deserving Refugees: The Migration Discourse in Hungary, 2015 and 2022

-

Author(s):Surányi, RáchelBognár, ÉvaPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. , No. online first, 2025, pp. 1-19DOI: 10.54667/ceemr.2025.23Received:

14 March 2024

Accepted:29 July 2025

Published:28 October 2025

Views: 962

The Hungarian government took an anti-immigrant and anti-refugee stance in 2015 and claims to have stuck to it ever since. However, in 2022, when many Ukrainians (including ethnic Hungarians) passed through Hungary after Russia started its invasion of Ukraine, the same government welcomed them. In this paper we illustrate how the Hungarian government’s approach shifted, without explicitly changing their main narrative but adding a new one to it: the aspect of deservingness. We also wanted to see the differences between the pro-government and the non-pro-government mediums. To illustrate this shift and the differences between the 2 platforms, we used qualitative methods: we analysed pro- and non-pro-government media during the 2015 and 2022 refugee crises and conducted expert interviews.

Introduction

In 2015, when the first influx of refugees reached Europe, the Hungarian government started its anti-immigration and anti-refugee propaganda by pressing the moral panic button or MPB (Sik and Gerő 2020). In 2022, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the same government welcomed the refugees arriving (or passing through) from the neighbouring country. It is important to stress that the ‘refugee hypocrisy’ (Traub 2022) is not a Hungarian-specific phenomenon. Europe had a different approach to the refugees in 2015 than to Ukrainian refugees in 2022; however, here we focus on Hungary, where the political environment (a modified version of informational autocracy – see Sik and Krekó 2025) enforces the constant use of migrants as scapegoats by pressing the MPB.

In this paper we illustrate how the Hungarian government’s approach shifted without explicitly changing their main narrative but by adding a new aspect to it. In other words, how did the narrative move from refugees and ‘undeserving/illegal/economic migrants’ to ’deserving refugees’? We focus on 2 periods of refugee influx in Hungary – 2015 and 2022 – and present the narratives through 2 case studies. We deviate from the routine of analysing migration narratives in Hungary from the securitisation aspect and examine them from a deservingness point of view.

The fact that the government is still continuously using the slogan ‘No migration! No gender! No war!’ shows the relevance of this paper at the domestic level. The anti-immigration stance is not unique to Hungary: there is a tendency in some European countries for mainstream parties to adopt the radical right-wing anti-immigration agenda.2

Research question and methodology

Our main research question is the following: What were the main migration narratives of the government and what were the differences in their presentation between the pro-government and the non-pro-government mediums and over time? We argue that, despite the Hungarian government’s claim that it has not changed its main narrative about refugees, it has added a new aspect to it: ‘deservingness’, based mainly on the cultural and civilisational similarity of this population with the Hungarian people.

In order to substantiate our argument and answer our research question, we used a qualitative methodology, namely media (content) analysis. Since 2010, the Hungarian government has significantly restructured the media landscape: it exercises control through various mechanisms, such as regulation, takeovers, state advertising, etc. (see more in Kovács, Polyák and Urbán 2021). Through these means, the Hungarian government exerts significant influence on public discourse, including agenda-setting, information flow and narrative-framing. This influence is particularly evident in the shaping of the media coverage of migration (Messing and Bernáth 2016). For this reason, we believe that analysing media discourse is a good way to form our analysis: the media shapes public opinion and reflects on what the government does.

We chose 2 specific periods/events which we believe best illustrate this shift in communication about immigrants. For 2015, we conducted a media analysis of the National Consultation on Immigration and Terrorism (NCIT) and, for the 2022 refugee crisis, we conducted a media analysis of the first week after the Russian invasion. For both periods we analysed some of the most read non-pro-government and pro-government mediums at that time. In 2015, we included 125 articles from 3 different outlets: a pro-government outlet (Magyar Idok), a non-pro-government centrist outlet but which was more critical of the government, with one of the largest readerships at the time (Index) and a non-pro-government liberal outlet (444). The study period is between the first mention of the national consultation (6 February 2015) and the end of the consultation (end of July 2015).

In 2022, the database consisted of 124 articles from 3 different online newspapers: Magyar Nemzet as the pro-government media and the main channel of the government, 24.hu as a non-pro-government centrist media – a left-wing portal with the aim to present an objective picture about migration in Hungary – and HVG.hu, the non-pro-government progressive media which regularly publishes political essays criticising the government. The articles were carefully selected on the basis of their heterogeneity and relevance to the topic. In both cases only those articles were chosen in which the selected topic covered a substantial part of the entire text. In the first case, the key phrase was ‘national consultation’ while, in the second case, the keyword was ‘refugee’ or ‘immigrant’ and the content had to relate to Ukrainians fleeing to Hungary.3 In both cases the articles were analysed manually with coding technique.

To complete the research, we conducted interviews with experts from different fields: activists, journalists, representatives of Hungarian and international NGOs, public officials and informal organisations. The interviews were only used for additional reference (for more on the methodology, see Bognár, Kerényi, Sik, Surányi and Szabolcsi 2023).

Reflections on the limitations

Since our paper is based on 2 different work packages within an EU project, there are some differences within the methodology. Regarding the 2 periods, we had to choose different case studies (as for every consortium partner) within the ‘refugee crisis’, therefore the keywords had to differ in the 2 periods. For the second phase, the Ukrainian refugee inflow seemed like an obvious choice since we were in the midst of the crisis. However, because both projects aimed at analysing the media narratives and the consortium agreed to our idea of analysing them in this way, we believe that it serves as a good basis for analysis – even if the focus (and the keywords) were different. Regarding the differences between the mediums, we could not choose the same because the Hungarian media landscape has changed. Regarding the pro-government mediums, one of them (Magyar Idők) was no longer available in 2022, and Index’s ownership had changed, which made us exclude them from the analysis. However, the strategy for both periods remained the same and, because we took into account the readership and the significance of the news outlets, we believe that they represent the 2 ‘sides’ perfectly.

The structure of this paper is as follows: first, we present the background theories that we apply in our analysis and make a detour into the Hungarian context. Then we present the data for 2015 by focusing on the NCIT, before analysing the data from the first week immediately after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Finally, we present our conclusions.

Migration narratives and deservingness

Migration became a hot topic in Hungary after 2015 but, unlike in many other European countries, where the topic soon died down, the Hungarian government has kept it on the agenda ever since. Recognising its success as a fear-mongering issue and, despite the fact that Hungary does not have a significant number of migrants and/or refugees, it has remained a crucial issue because it became part of the political propaganda (Benczes and Ságvári 2022; Bernát and Tóth 2022; Bognár, Sik and Surányi 2022; Reményi, Glied and Pap 2023).

There is an extensive literature on the deservingness of refugees and migrants which discusses how politics create hierarchies between and within groups of mobile populations (Anderson 2013; Holmes and Castañeda 2016; Ratzman and Sahraoui 2021). Deservingness has 3 distinct dimensions. The first is related to security, the second is economic and the third is cultural assimilability. Refugees – to be considered as deserving – must be economically useful, culturally assimilable and not pose a security threat to the country (Brekke, Paasche, Espegren and Sandvik 2021; Mourad and Norman 2020).

In order to be seen as deserving (…) refugees have to demonstrate that they are at risk in their countries of origin or first countries of refuge, yet willing and able to ‘overcome’ their vulnerability to become law-abiding, self-sufficient and culturally malleable future members of their host societies (Welfens 2023: 1104).

However, Welfens (2023) argues – applying the concept of ‘promising victimhood’ – that there is a tension between these 3 dimensions of assimilability and vulnerability. In her study, she focuses on how social markers (gender, age and race) influence the assessment of vulnerability and assimilability. We also use her arguments in this study to illustrate how the official perceptions of refugees are gendered, racialised and age-differentiated and which groups are considered ‘deserving’ or ‘undeserving’.

The Hungarian context

Since coming to power (in 2010), the Fidesz government has substantially restructured the media (see Sik and Krekó 2025) and has been using its hegemony not only to run almost continuous national billboard, TV and radio campaigns from public resources on various topics but also to launch smear-campaigns (even charade assassinations) against critics of the government (including politicians, journalists, members of civil society activists (Magyar Jeti 2023). Through these means, the Hungarian government has a dominant position from which to influence public discourse: on agenda setting, content of the discourse, information flow and language. Therefore, we believe that, by analysing the media discourses, we will receive an answer to our research questions. As a political analyst, Zoltán Lakner pointed out in a podcast (Klubrádió 2024) that even the non-pro-government media is expressing everything through the PM’s lens – such as saying ‘an ally of Orbán said…’ instead of using the person’s name.

There are 2 important migration-related features in Hungary: first that Hungary has only a small migrant population (who reside here permanently) and who are mostly ethnic Hungarians from neighbouring countries; and second, that xenophobia has been relatively high in Hungary since the 1990s (Surányi and Sik 2025) as part of a general intolerant value system that also includes prejudice against the Roma and the Jews as well (Bognár et al. 2022).

Although Hungary has never been a destination country, about 180,000 asylum-seekers passed through the country during the summer of 2015. Although they did not intend to stay, due to their unexpected arrival and large number, they were considered a threat to Hungary and therefore a fence was built along the Serbian–Hungarian border in September 2015 (Bernát, Fekete, Sik and Tóth 2019). In recent years, Hungary has been closed to asylum-seekers but human trafficking is still widespread and other types of migrant (guest workers, informal migrant workers and students) are also present.

At the beginning of 2015, the government launched a broad anti-immigration campaign, linking terrorism and immigration and changing Hungary’s asylum system through legal means – such as amending both the Asylum Act and the law (and its implementing regulation) on the entry and residence of third-country nationals, more than 30 times (Tóth 2020: 4) The modifications not only led to instability in the regulation related to immigration but also significantly changed Hungary’s asylum system.

In 2022, after Russia began its invasion of Ukraine, the existing legislation was a major obstacle, as it did not provide a way to enter Hungary as an asylum-seeker. Therefore, the Hungarian government amended the legislation to include temporary protection for people fleeing Ukraine and introduced new services for dual citizens (see Hungarian Helsinki Committee 2022).

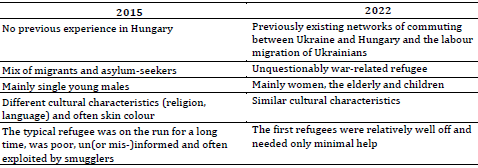

Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of the 2 refugee crises as perceived by the Hungarian population and the government. The perception does not necessarily reflect the reality but it is very close to it and provides a good basis for the following analysis.

Table 1. Hungarians’ perceptions of the migrants/refugees and migration processes in 2015 and 2022

Source: Gerő, Pokornyi, Sik and Surányi (2023: 7).

‘Illegal migrants’ in 2015 versus ‘real refugees’ in 2022

We have chosen 2 case studies to illustrate the differences in narratives. First, we examine the online media during NCIT in 2015, the first pressing of the MPB. Then we analyse the online media focusing on the refugee flow from Ukraine in 2022.

‘If you come to Hungary, you cannot take our jobs’ – NCIT

The ‘history’ of the MPB includes 9 push polls – labelled as ‘national consultations’ – to legitimise its policies and undermine criticism of the regime (Sik and Krekó 2025). Thus, the Orbán regime belongs to the group of authoritarian leaders who implement a variety of ‘innovations’ in order to prevent their loss of power, maintain the illusion of democratic legitimacy and control social conflicts and changes (Curato and Fossati 2020; He and Wagenaar 2018). In this section, we focus on the NCIT in 2015. We illustrate how its framing and propaganda techniques were designed to become the main fear- and crisis-mongering technique of the MPB (for the exact questions, see the Annex).

The use of the terms ‘migrant’ versus ‘refugee’ has become highly politicised: the former is used for people who choose to leave their home country for economic or other personal reasons, while ‘refugee’ is used for people who are forced to flee. While we agree with Crawley and Skleparis (2018), who argue that this is a simplistic approach and that the reasons why people left in 2015 were far more complex, it is still meaningful to analyse the use of these 2 terms in the media. Therefore, prior to the qualitative analysis of the narratives, we provide an overview of the word frequencies of the NCIT-related articles in the media in order to better understand the context.4 The most salient negative terms in these articles were as follows:5 fear (38 per cent), illegal (36 per cent), terror (22 per cent), bad (21 per cent), war (17 per cent), problem (16 per cent) and crisis (15 per cent). The more salient positive terms were: solution (26 per cent), unequivocal (16 per cent), proper (11 per cent) and help (10 per cent).

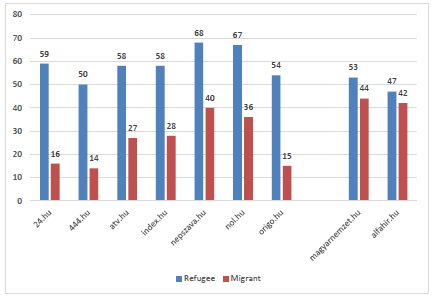

Regarding the 2 labels, we assumed that, while the pro-government media would use the label ‘migrant’ more often, the non-pro-government media would more frequently use the label ‘refugee’ – i.e. while the MPB would use the term with negative connotations to increase the level of threat, non-pro-government media outlets would not use such a labelling technique. Figure 1 shows that there is, indeed, a significant difference between the non-pro-government media (the first 7) and the pro-government (the last 2) media, although the labelling technique meant increasing the use of the term ‘migrant’ but not avoiding the term ‘refugee’ (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The trend of the MPB-determined labels by media outlets (%, 2015)

Source: Gerő et al. (2023).

The main narratives in 2015

The NCIT focused on the government’s anti-immigration and anti-refugee propaganda and policies. Two main opposing narratives were found in the articles with 1 or 2 side-narratives on each ‘side’. In the following section we highlight those aspects of the findings that relate to the immigrants/refugees and omit those details that relate to the technical and descriptive dimensions of the national consultation.

In the pro-government media outlet, the dominant migration narrative obviously supported the government’s view that migration was an inherently bad thing, as Orbán – deliberately using the term ‘economic migration’, referring to the fact that he does not consider people as asylum-seekers, i.e. people who deserve solidarity – said: ‘Economic migration is detrimental to Europe: one cannot think of it as something useful, because it only causes harm and danger to Europeans, so migration must be stopped, this is the Hungarian point of view’ (Dull and Miklósi 2015; see Figure 2).

Figure 2. National consultation billboard: ‘If you come to Hungary, you have to respect our culture’

Source: Kovács (2015).

In this narrative, the NCIT has been disguised as a public opinion survey on which an information campaign was built. The aim of these 2 actions was to legitimise the government’s anti-migrant actions – the government, though, had started acting before the results of the NCIT were available (Tóth 2022).

This narrative was supported by 2 sub-narratives. First, the government was using the method of fear-mongering: many articles in relation to the NCIT stated that migrants were flooding towards Hungary based on the fact that – as elsewhere in Europe – significantly more of them were actually arriving compared to the previous years. Or, as they put it, many illegal immigrants were being caught at the borders. Fear-mongering was one of the reasons why the word ‘illegal’ appeared so often, especially in the pro-government media. Fear-mongering was often achieved by using a vocabulary reminiscent of the way natural disasters and wars are described. For example: ‘Migrants continue to flood’ Hungary (Magyar Idők, 2015). People speaking for the government often used language like ‘invasion of immigrants’ or ‘we are witnessing the “mass migration of the modern times”’ (Herczeg 2015).

The use of this language by the pro-government media implies that they see migrants as a faceless mass. This is also due to the fact – as one expert pointed out in the interview – that, in 2015, Hungarian journalists hardly knew anything about what was happening abroad, especially in the MENA region and Africa in 2015. Therefore, there are only a few articles in which they write about the reasons why the Hungarian public is distanced from the events. Furthermore, Van Dijk (1997) argues that the use of these negative terms may contribute to the reproduction of racism in the country.

Since, according to the government, ‘there is a need to respond to the influx of economic migrants’, the second sub-narrative was the patriotic narrative. Its main message centred on the right to defend Hungary as opposed to accepting the European asylum policies imposed on the country. These articles questioned whose responsibility it was to defend Europe’s borders against the ‘enemy’ and/or to help migrants to stay in their countries of origin – allowing the government to position itself as generous and kind-hearted. As Orbán said: ‘It is not enough to defend Europe’s borders: we need to have a policy that helps those who flee to stay where they were born’ (Index 2015a). The solution to the paradox that Orbán’s constant criticism of the European Union (how it encroaches on Hungarian sovereignty) does not prevent him from expecting a common EU policy is that, in Orbán’s vocabulary, ‘real politics’ means selecting issues that are in his interest as ‘real EU policy’. To sum up the government’s point of view:

We consider it a fundamental value that Hungary is culturally, attitudinally, civilisationally and traditionally homogenous and we would prefer not to sacrifice this. But we also do not aim to contest the right of countries to accept refugees, countries who have by now gotten used to this and wish to solve their problems in this way. Hungary has a Christian government. There is mercy in our hearts, which is why we have always welcomed the persecuted and will continue to do so. But the people arriving in Hungary today are not like this, they are economic migrants (Index 2015a).

This quote clearly states that these people are not refugees but economic migrants – therefore undeserving – and that there would be cultural conflicts with accepting them nor do we want to increase civilisational tensions in Hungary. Although solidarity is mentioned – stemming from the Christian nature of the state – it is likely to be more than a ‘fig leaf’. As Orbán pointed out: ‘Brussels wants them to stay and let others keep coming. We want them to stop coming and those who are already here to go home’. He said that he wanted to control who could enter the country and that he would not agree to a common European immigration/refugee policy, because ‘It is the most elementary right of a country to decide who may cross its borders. “The only reason why we cannot send them home and have to let them in, is that EU regulations force us to do so”. The issue of immigration must therefore be returned to the jurisdiction of the member states or the EU regulations have to be changed’ (Losonczi and Bákonyi 2015). Finally, the government’s view was that the left-wing opposition supports immigration and aims to damage the country, i.e., they are against national interests.

The third – security – aspect of deservingness also appeared in several cases: the government communicated the risk posed by migrants to the wellbeing of the local population. This was pushed by one of the ‘questions’ in the NCIT (No. 5, see Annex), as well as by sentences on the government’s billboards and television spots such as ‘If you come to Hungary, you cannot take our jobs’. This issue touches upon the conflict of the migrants, on the one hand, being economically fit to be accepted in the country but, on the other, not to be in competition (for employment) with their co-nationals. Then there is the terrorist variant of the demonisation process. The whole NCIT was based on the assumption that migration and terrorism are inherently intertwined.

There is a correlation between immigration and terrorism. Those who arrive in Europe split from their cultural community, and we can see the consequences of this in Western Europe. They can form an unusual subculture that has the potential of becoming a deviant, fertile soil for criminality (Bence Tuzson, cf. Joób and Dull 2015).

Not surprisingly, these people are portrayed as ‘terrorists’ who pose a ‘security threat’ to the country – they are not ‘deserving’. As was sarcastically put in an article published in a non-pro-government newspaper: ‘Economic migrants are frauds. Arsonists. Thieves. Brutes. Spreaders of disease. Terrorists. And the communists like them. Get them out of Hungary’ (Dull 2015).

The terrorist framing – among others – was also found in the Slovak case by Kissová (2018) who also explored the deservingness in the political discourse regarding refugees in 2015. Furthermore, she argues that the 4 V4 countries behaved in a very similar way, so this is not a regional issue but, rather, concerns the whole CEE region. However, as we argue, the case of Hungary – with its MPB techniques and the whole context – stands out as a form of informational autocracy (Sik and Krekó 2025), which is not the case in Slovakia, Poland and the Czech Republic.

In contrast to the pro-government approach, non-pro-government media outlets took a socially sensitive approach towards refugees/migrants: refugees should not be seen as threats but should be helped. These media outlets mainly treated asylum-seekers as genuine refugees and not as ‘economic migrants’. Their counter-narrative was that the NCIT was ‘a political communication tool aimed at mobilising pro-government sympathisers and diverting attention from the country’s real (social) problems’:

Fidesz and PM Viktor Orbán have begun the divisive billboard campaign about immigration to distract from the issues of unemployment and education. ‘It is not migrants and migration that interests Viktor Orbán but the decreasing popularity of Fidesz’ (Index 2015b).

The opposition voiced that Orbán was trying to gain power through his anti-migrant policies, which he used to divert the attention from the country’s problems such as education, health care etc.

The representation of refugees in 2015

While there was no difference between pro- and non-pro-government media in terms of not giving a voice to refugees themselves, our analysis was inconclusive regarding the visualisation of migrants, as the photos were not available in the pro-government medium (Magyar Idők). However, other research showed that the pro-government media reinforced the anti-refugee stance of the government in their visualisation: they ‘alienated viewers from refugees by illustrating news reports with images dominated by faceless crowds, aggressive youths or people being arrested and by avoiding images which portrayed children or human moments’ (Bernáth and Messing 2015: 59). In contrast, non-government illustrations tended to focus on individuals (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. A typical illustration of refugees in 2015 in the non-government media

Source: dsz (2015).

The ‘real refugees’ of 2022

Contrary to previous findings from 2015, the articles did not differ significantly between pro-government and non-pro-government media outlets. Almost all articles focused on the help that Hungary or the Hungarians have offered to the refugees. The 2 most often occurring narratives were that (1) the Hungarian state welcomes and helps refugees by uniting its diverse political forces and (2) that Hungarians (the civil society) help the refugees in every possible way.

Regarding the first narrative, the main message was that Hungary is preparing to receive refugees and that the state is coordinating assistance to make their arrival as smooth as possible. This includes ensuring free health care (the government to provide medical and hospital care for Ukrainian refugees arriving in Hungary – Spirk 2022), extending the opening hours at the border crossings (Magyar Nemzet 2022a), offering a solidarity ticket ensuring free transportation for refugees on the Hungarian national railway (Magyar Nemzet 2022b) and mobilising the Hungarian Defence Forces (HVG 2022a) – thus changing the legal system. One interviewee working in an NGO summarised it as follows: ‘You think of something which should be done [as a helper] and tomorrow it is already a government resolution. That was the way the spring went’. For example, on 24 February there was an article stating that the Hungarian legal system needed to be changed in order to be able to accept refugees (Farkas 2022a) and, on 25 February, there was a government communiqué stating that permanent asylum should be granted to Ukrainians coming from Ukraine (Farkas 2022b). This change in the law also allowed for the entry of third-country nationals who had legal status in Ukraine. This narrative expressed the willingness of the government to help – because these people deserve solidarity. However, it is important to emphasise that not everyone was satisfied with the level of state assistance (see, for example, Doros 2022; Rényi 2022).

Regarding the second narrative, we found only small but significant differences between pro- and non-pro-government media. While the narratives of the Magyar Nemzet emphasised the leading role of Fidesz in coordinating the Hungarian help (via the Bridge for Sub-Carpathia or the state-governed NGO Ökumenikus Segélyszervezet), the non-pro-government media highlighted the key role of the Hungarian people and NGOs in providing aid (see more on this issue in Tóth and Bernát 2024). However, this difference was almost insignificant in the database.

About a quarter of the articles (N=34) were dedicated to initiatives of some prominent individuals – such as politicians (Gabay 2022) and artists (Magyar Nemzet 2022c), organisations (such as the ELTE University; see 24.hu 2022) or the University of Theatre and Film Arts (Magyar Nemzet 2022d) etc.) and companies – e.g. Airbnb (HVG 2022b), Wizz Air (HVG 2022c) – that offered help during the crisis.

As mentioned above, narratives about NGOs and civil society helping Ukrainian refugees became a hot topic from the first day of the war for 2 reasons. This was the case, firstly, since most of the asylum system was dismantled after 2015 and thus there was no institutional background to address the needs of the large number of refugees. This required the help of civil society – both formal organisations and informal networks. According to several studies, 7 per cent of the Hungarian population volunteered and, overall, 40 per cent of the population helped in some way, mostly with donations (Surányi and Sik 2025; Zakariás, Feischmidt, Gerő, Morauszki, Neumann, Zentai and Zsigmond 2023).

Secondly, civil society plays a controversial role in public discourse: since 2014, NGOs are often identified in government discourse as ‘liberal political activists’, allies of George Soros or the so-called ‘Soros army’ (see Kopper, Susánszky, Tóth and Gerő 2017; Majtényi, Kopper and Susánszky 2019). The mushrooming of reactivated (dormant since the 2015 refugee crisis) and new civic initiatives to support asylum-seekers (Tóth and Bernát 2022) led to the temporary alliance of NGOs and the government in the MPB framing: the two arch-enemies. Given the lack of institutional resources, the government found itself forced to rely on NGOs (Tóth and Bernát 2022).

The third most common narrative was that the refugees, in 2015, were undeserving ‘illegal immigrants’, whereas those fleeing from Ukraine were deserving ‘real refugees’. This narrative appeared mostly in the pro-government medium but these narratives were reinforced by the non-pro-government mediums (though without expressing agreement with – and sometimes even criticising – them).

This narrative had several themes. First, they tried to frame it in terms of age and gender. In contrast to the 2015 crisis, when it was mainly young men who crossed into Hungary (who, according to the MPB narrative, should have stayed in their country to fight), this time it was mainly (elderly) women and children who, in the eyes of many, were more deserving (although this goes against the economic aspect of deservingness as they are less likely to contribute to the economic growth of the country – Welfens 2023). The following extract from an article published in a pro-government newspaper is a good (if sarcastic) summary of all these arguments:

Looking at the painful photos of the crisis in Ukraine, one can see what a real flood of refugees looks like. It’s a revealing sight: women fleeing, small children, elderly men – but no head of household. How could there be? He stayed at home to fight, to resist. And how interesting, every refugee has papers, ID cards… even if in many places they are not asked for them. Let’s remember these pictures! Real refugees…

This crowd is not made up of men in their 20s smoking cigarettes and using mobile phones, most of whom, when asked, claim to be 18 years old (because they somehow ‘lost’ their documents while fleeing...). There are no young men with Soros bank cards and hundreds of Euros in their pockets... (Pilhál 2022).

In short, ‘real refugees’ have to be poor and have legal documents – this makes them more deserving. Pilhál (2022) continues with the basic MPB frame: ‘A refugee is only a refugee until the first safe country, after that he is a tourist. And anyone who tries to enter the third country illegally, without papers and by force is a terrorist’. Hungary welcomes ‘real refugees’ from Ukraine because they come from a neighbouring country and at the border they ‘behave well’:

(…) the most fundamental human right is the right to safe and peaceful living conditions and this right of the Ukrainian people has been seriously violated, with many of them having to leave their homes. (...) All border crossings are open, all Ukrainian citizens and those who have been legally present on the territory of Ukraine are allowed to enter… and that Hungary, as the first safe country, was doing its duty to help them. The minister (…) refused to draw any parallels between refugees from Ukraine and illegal migrants. Illegal migrants often behave aggressively and want to cross the green border but refugees from Ukraine come to the border crossing points and wait in a disciplined and patient manner (Magyar Nemzet 2022e).

This is exactly what one of our interviewees expressed in a sarcastic way:

This is how a refugee should look (…) the man stays home, defending the house, and the child and the women come with blue eyes cried out, blondies and politely standing in queue at the border and very grateful for the help distributed to them. And we do everything we can to help etc.

In 2015, however, a pro-government politician described it as follows: ‘Illegal migrants were streaming across our southern borders... only men of working or military age, as they say, men in a closed formation, in mass groups, which obviously does not show the picture of those fleeing war, but of those going to war, to any right-thinking person’.

This is related to knowledge of the cause of the crisis: while, in 2015, Hungarians were not fully aware of the reasons why so many people from Africa and Asia were on their way to Europe, by 2022 Europe had been closely following the crisis that has been unfolding since 2014 and which culminated in February 2022. Therefore, the likelihood of knowing why Ukrainians were fleeing was much higher and since most governments were pro-Ukraine, it was easier to sympathise with them.

A pro-government expert used the same argument in the interview when explaining why the government did not change its narrative between 2015 and 2022: now refugees arrive in Hungary as their first safe country, compared to migrants in 2015 who came mostly through Serbia, which the government considers to be a safe country. This argument, however, does not contradict the government’s unspoken claim of deservingness: while the migrants in 2015 were undeserving because of their cultural and civilisational deviation from the homogeneous Hungarian society, in 2022 they were deserving because of the civilisational similarity and the clarity of the reason for their flight (fleeing from war).

A fourth, albeit marginal, narrative was that the Carpathian Roma did not get enough help. Discrimination against Roma refugees (Bokros and Galicza 2022) posited that they were ‘the least likely to receive better accommodation and care’ (Tóth and Bernát 2024: 284). However, this issue was only mentioned in the non-pro-government media. In the pro-government media there was one article about the Roma, which also said how much help they received.

The fifth, also marginal, narrative was that Hungary wanted to stay out of the war because it stood for peace. This was one of the main government narratives about the war and it appeared as early as the first week. One non-pro-governmental interviewee illustrated lucidly the misuse of a historical narrative of Hungary (defending Europe as the ‘last bastion’ of the Ottoman Empire): whereas, in 2015, Hungary was ‘the last bastion of Europe defending Christianity’, in 2022 it was ‘the last bastion of peace’.

The representation of refugees in 2022

Despite the generally similar narratives, the representation of refugees in the pro-and non-pro-government media differed significantly. While there were several articles in the latter that quoted the refugees, we found only one article in the pro-government medium that gave them a voice.

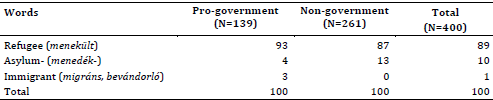

The framing of the crisis can also be captured by the labelling technique: compared to the 2015 refugee crisis, where those arriving were often referred to as (illegal) migrants, in 2022 it was almost unanimously agreed that these were people fleeing from war and were deserving refugees, therefore, the term ‘migrant’ almost never occurred (Table 2).

Table 2. The proportion of the 3 main labels in the pro- (48 articles) and non-government media (76 articles) – % of all mentions

Looking at the photos, we identified 2 types. If the photo illustrated the refugees (Figure 4), there was no difference between the pro- and non-pro-government media. However, when the photo illustrated something else, in the pro-government media it was usually a politician, in the non-pro-government media, it was either related to the war (soldiers) or a screenshot of a Facebook post (an announcement they wanted to share).

Figure 4. A typical illustration of refugees in 2022

Source: Papp (2022).

Conclusion

In this paper we present the qualitative analysis of 2 case studies – the national consultation in 2015 and the Ukrainian refugee crisis in 2022 – of how the Hungarian pro-government and non-pro-government media approached the selected issues. Our aim was to illustrate the changes (if any) in the narratives. Since our understanding is that Hungary is an informational autocracy where the government presses the moral panic button whenever it deems it necessary, our analysis looks at both the pro-government channels (the mouthpieces of the government) and the non-pro-government channels (where these narratives should not be dominant).

From these content analyses we learnt that, while, in 2015, the refugees were perceived as illegal immigrants, mostly Muslims (i.e. potential terrorists) coming from outside Europe, who do not deserve our help, in 2022 the main understanding was that they were (European) people (asylum-seekers/refugees) who were fleeing war and therefore deserved the temporary help provided. While, in the first case, there was a sharp contrast between ‘them’ and ‘us’ (Hungarians or Europeans), in the second case, both Ukrainians and Hungarians were part of ‘us’, therefore they deserved our help.

In 2015, we consistently found only the pro-government narrative in the pro-government media. There was a clear division/opposition between pro-government and non-pro-government media: the focus of the former was to show that the refugees crossing into Hungary were illegal immigrants who did not deserve help. Other narratives appeared in the non-governmental media under the theme of solidarity.

In 2022, all those who arrived were treated as victims of war and therefore could be trivially considered as ‘real refugees’ in contrast to the ‘mix of masses’ during the refugee crisis of 2015. This difference was reinforced by comparing the social indicators (age, gender, culture, religion etc.) of the 2 populations: the former were mostly single young males with Muslim/Arab backgrounds and the latter mostly women and children – often families with Ukrainian backgrounds.

These differences explain why, in 2022, both pro-government and non-pro-government media shared the same main narratives. The only narrative difference was related to the role of the state versus that of civil society: the pro-government media emphasised the leading role of Fidesz in coordinating the Hungarian help; the non-pro-government media highlighted the key role of the Hungarian people and NGOs in providing it. The portrayal of the refugees was also similar in all mediums but, in the non-pro-government media, the refugees were given more voice than in the pro-government media.

The Hungarian government has tried to posit that they did not change their main narrative between 2015 and 2022: it will only accept people in the country for whom this is the first safe country. This claim is only valid if we accept that Serbia can be considered as a safe country, which was not necessarily the position of the international organisations.6 In 2022, however, the Hungarian government added another narrative to their still dominant anti-migrant MPB one: the differentiation between deserving and undeserving refugees, which was largely based on several aspects such as social, cultural and economic indicators.

Notes

- In this paper we use the results of an earlier project funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Innovation and Research Programme under Grant Agreement No. 101004564 (Bridges). Therefore, parts of this paper were taken from other sources with the permission of the authors: Márton Gerő, Endre Sik, Zsanett Pokornyi and Péter Kerényi.

- See Vohra (2023).

- Excluding those where they wrote about Ukrainian refugees fleeing to Romania and Poland or where they wrote about other border crossings, not connected to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- The following paragraphs refer to the database with articles containing the term ‘national consultation’ (N=831) from which we selected the articles for qualitative analysis.

- The ratio refers to those articles in which the given term is mentioned at least once.

- https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/world_report_download/wr2016_web... https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur70/1579/2015/en/.

Funding

This research was funded by the project ‘BRIDGES: Assessing the Production and Impact of Migration Narratives’ (Grant Agreement No. 101004564): https://www.bridges-migration.eu/.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reprted by the authors.

ORCID IDs

Ráchel Surányi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2665-0250

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2665-0250

References

24.hu (2022). Az ELTE segítséget nyújt az ukrajnai menekülteknek. 24.hu, 25 February. https://24.hu/tudomany/2022/02/25/ukran-orosz-haboru-konfliktus-ukrajna-... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Anderson B. (2013). Us and Them? The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Benczes R., Ságvári B. (2022). Migrants Are Not Welcome: Metaphorical Framing of Fled People in Hungarian Online Media, 2015–2018. Journal of Language and Politics 21(3): 413–434.

Bernát A., Fekete Z., Sik E., Tóth J. (2019). Borders and the Mobility of Migrants in Hungary. CEASEVAL Working Papers No. 29. https://www.cidob.org/en/publications/borders-and-mobility-migrants-hungary (accessed 20 August 2025).

Bernát A., Tóth J. (2022). Menekültválság 2022-ben: Az Ukrajna elleni orosz agresszió menekültjeinek magyarországi fogad(tat)ása, in: T. Kolosi, I. Szelényi, I.G. Tóth (eds) Társadalmi Riport 2022, pp. 347–367. Budapest: Tárki.

Bernáth G., Messing V. (2015). Wiped out. The Government’s Antiimmigration Campaign and Opportunities to Raise an Independent Voice. http://www.mediakutato.hu/cikk/2015_04_tel/01_menekultek_moralis_panik.pdf

Bognár É., Sik E., Surányi R. (2022). The Operation of the Moral Panic Button, in: É. Gedő, É. Szénási (eds) Populism and Migration, pp. 105–125. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Bognár É., Kerényi P., Sik E., Surányi R., Szabolcsi Z. (2023). Migration Narratives in Media and Social Media. Bridges Working Paper. https://www.bridges-migration.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/WORKING-PAPE... (accessed 20 August 2025).

Bokros D., Galicza D. (2022). ‘Nagyon gyorsan felmérik azt, hogy ők senkinek nem kellenek’ – riport az Ukrajnából menekült roma családokról. hvg.hu, 30 April. https://hvg.hu/itthon/20220430_Nagyon_gyorsan_felmerik_azt_hogy_ok_senki... (accessed 20 August 2025).

Brekke J.P., Paasche E., Espegren A., Sandvik K.B. (2021). Selection Criteria in Refugee Resettlement. Balancing Vulnerability and Future Integration in Eight Resettlement Countries. Institutt for Samfunnsforskning. https://samfunnsforskning.brage.unit.no/samfunnsforskning-xmlui/handle/1... (accessed 20 August 2025).

Crawley H., Skleparis D. (2018). Refugees, Migrants, Neither, Both: Categorical Fetishism and the Politics of Bounding in Europe’s ‘Migration Crisis’. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44(1): 48–64.

Curato N., Fossati D. (2020). Authoritarian Innovations: Crafting Support for a Less Democratic Southeast Asia. Democratization 27(6): 1006–1020.

Doros J. (2022). Menekültválság: fáradnak a civilek és az önkéntesek, de az állam még mindig nem találja a helyét a rendszerben. Népszava, 9 March. https://nepszava.hu/3149316_ukrajna-haboru-menekultek-civilek (accessed 2 September 2025).

dsz (2015). Az Együtt népszavazásra viszi Orbán kérdéseit. Index, 28 May. https://index.hu/belfold/2015/05/28/az_egyutt_nepszavazasra_viszi_orban_... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Dull S. (2015). Gyűlölethadjáratot indított a Fidesz a menekültek ellen. Index, 20 February. https://index.hu/belfold/2015/02/20/gyulolethadjaratot_inditott_a_fidesz... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Dull S., Miklósi G. (2015). Miért jó Orbánnak a kíméletlen harc a bevándorlókkal? Index, 16 June. https://index.hu/belfold/2015/06/16/miert_jo_orbannak_a_kimeletlen_harc_... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Farkas G. (2022a). Helsinki Bizottság: a háború miatt új menekültügyi szabályozás kell. 24.hu, 24 February. https://24.hu/belfold/2022/02/24/ukrajna-haboru-menekultek-helsinki-bizo... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Farkas G. (2022b). Rendkívüli kormánydöntések az orosz-ukrán háború miatt. 24.hu, 25 February. https://24.hu/belfold/2022/02/25/orosz-ukran-haboru-rendkivuli-kormany-r... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Gabay D. (2022). A XVI. kerület fogadja a kárpátaljai menekülteket. Magyar Nemzet, 25 February. https://magyarnemzet.hu/belfold/2022/02/a-xvi-kerulet-fogadja-a-karpatal... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Gerő M., Pokornyi Z., Sik E., Surányi R. (2023). The Impact of Narratives on Policy-Making at the National Level. BRIDGES Working Paper 22. https://www.bridges-migration.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/BRIDGES-Work... (accessed 20 August 2025).

He B., Wagenaar H. (2018). Authoritarian Deliberation Revisited. Japanese Journal of Political Science 19(4): 622–629.

Herczeg M. (2015). Ez lett a nagy, 1 milliárd forintos, bevándorlók ellen hergelő nemzeti konzultáció eredménye. 444.hu, 27 July. https://444.hu/2015/07/27/ez-lett-a-nagy-milliardos-bevandorlok-ellen-he... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Holmes S.M., Castañeda H. (2016). Representing the ‘European Refugee Crisis’ in Germany and Beyond: Deservingness and Difference, Life and Death. American Ethnologist 43(1): 12–24.

Hungarian Helsinki Committee (2022). Tájékoztató az Ukrajnából menekülők jogi helyzetéről. https://helsinki.hu/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Tajekoztato-az-Ukrajnabol... (accessed 2 September 2025).

HVG (2022a). Egyre több magyar katona vonul a keleti országrészbe. hvg.hu, 28 February. https://hvg.hu/itthon/20220224_Egyre_tobb_magyar_katona_megy_a_keleti_or... (accessed 2 September 2025).

HVG (2022b). Százezer ukrajnai menekültnek nyújt ingyen szállást az Airbnb. hvg.hu, 28 February. https://hvg.hu/ingatlan/20220228_ukrajna_menekultelk_ingyen_szallas_airbnb (accessed 2 September 2025).

HVG (2022c). Százezer ingyenes repülőjeggyel segíti az Ukrajnából menekülőket a Wizz Air. hvg.hu, 2 March. https://hvg.hu/kkv/20220302_ukran_menekultek_ingyenes_repulojegy_wizz_air (accessed 2 September 2025).

Index (2015a). Orbán: Európa határait meg kell védeni. Index, 24 April. https://index.hu/belfold/2015/04/24/orban_mindenki_lephet_egyet_elore/ (accessed 2 September 2025).

Index (2015b). Feljelent a Fidesz a plakátrongálások miatt. Index, 7 June. https://index.hu/belfold/2015/06/07/feljelent_a_fidesz_a_plakatrongalaso... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Joób S., Dull Sz. (2015). Tényleg kórokozókat terjesztenek a munkahelyeinket veszélyeztető, dolgozni nem akaró terrorista menekültek? Index, 11 June. https://Index.hu/belfold/2015/06/11/menekultek_bevandorlas_menekultugy_m... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Kissová L. (2018). The Production of (Un)Deserving and (Un)Acceptable: Shifting Representations of Migrants within Political Discourse in Slovakia. East European Politics and Societies 32(04): 743–766.

Klubrádió (2024). Reggeli Személy. Klubrádió, 25 January. https://www.klubradio.hu/archivum/reggeli-gyorsreggeli-szemely-2024-janu... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Kopper Á., Susánszky P., Tóth G., Gerő M. (2017). Creating Suspicion and Vigilance: Using Enemy Images for Hindering Mobilization. Intersections. East European Journal of Society and Politics 3(3): 108–125.

Kovács A. (2015). Ezért mehettek neki Orbánék a bevándorlóknak. Origo, 11 June. https://www.origo.hu/itthon/2015/06/orban-viktor-bevandorlo-menekult-kam... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Kovács I., Polyák G., Urbán Á. (2021). Media Landscape after a Long Storm. https://mertek.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/MertekFuzetek25.pdf (accessed 21 January 2025).

Losonczi K., Bákonyi Á. (2015). Érvek és ellenérvek. Magyar Idők, 29 May. https://www.magyaridok.hu/belfold/ervek-es-ellenervek-481615/ (accessed 2 September 2025).

Magyar Idők (2015). A baloldal azért nem szereti a magyarokat, mert magyarok. Magyar Idők, 27 July. https://www.magyaridok.hu/belfold/a-baloldal-azert-nem-szereti-a-magyaro... (accessed 21 August 2025).

Magyar Jeti (2023). Valótlanul: fekete kampányok az Orbán-rendszerben. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ego4aQLZKlQ (accessed 21 August 2025).

Magyar Nemzet (2022a). Hosszabbított nyitvatartással üzemel két magyar-ukrán határátkelőhely. Magyar Nemzet, 24 February. https://magyarnemzet.hu/kulfold/2022/02/hosszabbitott-nyitvatartassal-uz... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Magyar Nemzet (2022b). Ingyen utazhatnak az ukránok a MÁV belföldi járatain. Magyar Nemzet, 28 February. https://magyarnemzet.hu/gazdasag/2022/02/ingyen-utazhatnak-az-ukranok-a-... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Magyar Nemzet (2022c). Sebestyén Márta is segít a háborús menekülteknek. Magyar Nemzet, 2 March. https://magyarnemzet.hu/kultura/2022/03/sebestyen-marta-is-segit-a-habor... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Magyar Nemzet (2022d). A Színház- és Filmművészeti Egyetem is segíti a háborús menekülteket. Magyar Nemzet, 27 February. https://magyarnemzet.hu/kultura/2022/02/a-szinhaz-es-filmmuveszeti-egyet... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Magyar Nemzet (2022e). Szijjártó: Az Ukrajnából menekülők és az illegális migránsok között nem lehet párhuzamot vonni. Magyar Nemzet, 2 March. https://magyarnemzet.hu/kulfold/2022/03/szijjarto-az-ukrajnabol-menekulo... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Majtényi B., Kopper Á., Susánszky P. (2019). Constitutional Othering, Ambiguity and Subjective Risks of Mobilization in Hungary: Examples from the Migration Crisis. Democratization 26(2): 173–189.

Messing V., Bernáth G. (2016) Infiltration of Political Meaning: The Coverage of the Refugee ‘Crisis’ in the Austrian and Hungarian Media in Early Autumn 2015. https://cmds.ceu.edu/sites/cmcs.ceu.hu/files/attachment/article/1041/inf... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Mourad L., Norman K.P. (2020). Transforming Refugees into Migrants: Institutional Change and the Politics of International Protection. European Journal of International Relations 26(3): 687–713.

Papp A. (2022). Két nap alatt 1600 menekült érkezett Záhonyba. 24.hu, 25 February. https://24.hu/belfold/2022/02/25/zahony-menekult-ukrajnai-haboru-magyaro... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Pilhál G. (2022). Igazi menekültek. Magyar Nemzet, 28 February. https://magyarnemzet.hu/tollhegyen/2022/02/igazi-menekultek (accessed 2 September 2025).

Ratzman N., Sahraoui N. (2021). State of the Art. Conceptualising the Role of Deservingness in Migrants’ Access to Social Services. Social Policy and Society 20(3): 440–451.

Reményi P., Glied V., Pap N. (2023). Good and Bad Migrants in Hungary. The Populist Story and the Reality in Hungarian Migration Policy. Social Policy Issues 59(4): 323–344.

Rényi P.D. (2022). Most üt vissza, hogy 2015 után a kormány szétverte a menekült-ellátórendszert. 444.hu, 22 March. https://444.hu/2022/03/22/most-ut-vissza-hogy-2015-utan-a-kormany-szetve... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Sik E., Gerő M. (2020). The Moral Panic Button: Construction and Consequences, in: E.M. Gozdziak, I. Main, B. Suter (eds) Europe and the Refugee Response, pp. 39–58. London: Routledge.

Sik E., Krekó P. (2025). Hungary as an Ideological Informational Autocracy (IA) and the Moral Panic Button (MPB) as its Basic Institution. Central and Eastern European Migration Review.

Spirk J. (2022). Emmi: Biztosítják az ukrajnai menekültek egészségügyi ellátását. 24.hu, 2 March. https://24.hu/belfold/2022/03/02/emmi-ukrajnai-menekultek-egeszsegugyi-e... (accessed 20 August 2025).

Surányi R., Sik E. (2025). Similar but… The Trend of Xenophobia in Hungary and Poland. Central and Eastern European Migration Review.

Tóth J. (2020). Szerkesztői előszó. Korszakhatáron, avagy búcsú a menedékjogtól. Állam-és jogtudomány 60(4): 3–10.

Tóth J. (2022). On the Edge on an Epoch, or a Farewell to Asylum Law and Procedure, in: É. Gedő, É. Szénási (eds) Populism and Migration, pp. 175–193. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Tóth J., Bernát A. (2022). Menekültválság 2022-ben: az Ukrajna elleni orosz agresszió menekültjeinek magyarországi fogadása, in: T. Kolosi, I.G. Szelényi (eds) Társadalmi Riport 2022, pp. 347–367. Budapest: Tárki.

Tóth J., Bernát A. (2024). Solidarity Driven by Utilitarianism: How Hungarian Migration Policy Transformed and Exploited Virtues of Solidarity, in: F. Fauri, D. Mantovani (eds) Past and Present Migration Challenges: What European and American History Can Teach Us, pp. 271–295. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Traub J. (2022). The Moral Realism of Europe’s Refugee Hypocrisy. Foreign Policy, 21 March. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/21/ukraine-refugees-europe-hyporcrisy-... (accessed 2 September 2025).

Van Dijk T. (1997). What Is Political Discourse Analysis, in: J. Blommaert, C. Bulcaen (eds) Political Linguistics, pp. 11–52. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Vohra A. (2023). The Far Right Is Winning Europe’s Immigration Debate. Foreign Policy, 1 November. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/11/01/the-far-right-is-winning-europes-im...(accessed 2 September 2025).

Welfens N. (2023). ‘Promising Victimhood’: Contrasting Deservingness Requirements in Refugee Resettlement. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49(5): 1103–1124.

Zakariás I., Feischmidt M., Gerő M., Morauszki A., Neumann E., Zentai V., Zsigmond C. (2023). Szolidaritás az ukrajnai menekültekkel Magyarországon: gyakorlatok és attitűdök egy lakossági felmérés alapján. Regio 31(2): 101–150.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.