In the Pursuit of Justice: (Ab)Use of the European Arrest Warrant in the Polish Criminal Justice System

-

Author(s):Klaus, WitoldWłodarczyk-Madejska, JustynaWzorek, DominikPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2021, pp. 95-117DOI: 10.17467/ceemr.2021.02Received:

17 February 2020

Accepted:8 April 2021

Published:7 May 2021

Views: 17116

Poland is the leading country in pursuing its own citizens under the European Arrest Warrant (EAW), with the number of EAWs issued between 2005 and 2013 representing one third of the warrants issued by all EU countries (although some serious inconsistencies between Polish and Eurostat statistical data can be observed). The data show that Poland overuses this instrument by issuing EAWs in minor cases, sometimes even for petty crimes. However, even though this phenomenon is so widespread, it has attracted very little academic interest thus far. This paper fills that gap. The authors scrutinise the topic against its legal, theoretical and statistical backdrop. Based on their findings, a theoretical perspective is drawn up to consider what the term ‘justice’ actually means and which activities of the criminal justice system could be called ‘just’ and which go beyond this term. The main question to answer is: Should every crime be pursued (even a petty one) and every person face punishment – even after years have passed and a successful and law-abiding life has been building in another country? Or should some restrictions be introduced to the law to prevent the abuse of justice?

Introduction

The attitude of societies and states to crime and punishment changes over time and space. Definitions of what constitutes a crime and what punishments should be handed out for particular crimes are constantly redefined. Even the concept of punishment and what should be considered as such evolves (Black 2011). The attitudes change along with changes in developing societies and political systems. For centuries, banishment was the most acute and severe punishment – excluding the offender from the society. If such an individual fled a particular country, nobody would be normally go looking for them or demand extradition from the country to which they went. It was not until the eighteenth century that international cooperation with regards to fighting crime began to emerge, initially concentrating on prosecuting political and religious ‘criminals’. The rules for transferring ‘common criminals’ between countries were formulated at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when extradition was no longer treated as an instrument with which to exercise political power but rather as a tool of the justice system. At first, international law provisions regulating extradition focused mainly on the perpetrators of the most serious crimes – i.e. war crimes or crimes against humanity (Wierzbicki 1992). Only after international institutions developed and tighter international cooperation was established in the second half of the twentieth century were the foundations for cooperation between countries on criminal cases laid down, with the mutual surrender of wanted criminals as one of its elements.

The trend is by no means one way only. In the twentieth century, we saw cases motivated by opposite intentions – not only were escaped criminals not pursued by governments of the countries from which they had fled but, in several instances, their ‘export’ to other countries was actively supported by some governments. Such occurrences took place in 1980 in Cuba, where Fidel Castro’s regime released several thousand serious criminals from prison and allowed them to leave the country (together with over 100,000 dissidents). The communist government in Poland took a leaf out of Castro’s book and, between 1982 and 1988, allowed several hundred offenders (released from prison for this specific reason) to go abroad, accompanying several thousand opposition activists forced to emigrate – often also released from prison or internment in order to facilitate the departure (Stola 2012: 315–319).

The most developed international cooperation and an attempt at harmonising criminal justice systems is evident in the European Union (Szwarc-Kuczer 2011). One of the first acts of judicial cooperation between EU member states was the Council Framework Decision of 13 June 2002 on the European arrest warrant and the surrender procedures between member states (2002/584/JHA – hereinafter referred to as the Framework Decision). The aim of the Decision was the continuation of the development of judicial cooperation between EU member states with respect to criminal law. In order to promote it, the Decision introduced innovative solutions – namely the European Arrest Warrant (EAW), which replaced the existing regulations on extradition based on other international law provisions.

Compared to the traditional model of extradition, the important feature introduced by the EAW is the stripping-of-surrender procedure of its political element – i.e. the possibility of politicians interfering in decisions pertaining to the prosecution or surrender of a given person. It is the result of transferring this competence exclusively to courts. The procedure itself was also simplified to a great extent. However, surrender under the EAW is conditional since the issuing country does not abdicate its jurisdiction over the surrendered individual, as is the case with classic extradition (cf. West, C-192/12 PPU).

The Framework Decision allows for independent decisions by member states on how it will be implemented – decisions only limited by the obligation to realise the goal of the Decision. The practice of applying the EAW has demonstrated, however, that some countries, including Poland, use the EAW contrary to the assumptions of the system, requesting the extradition of not only ‘serious criminals’ but also of fairly minor offenders (Böse 2015: 143), frequently many years after the trial. Poland is the leading country in pursuing its own citizens under the EAW and, between 2005 and 2013, issued one third of all issued warrants in the EU (although some serious inconsistencies between Polish and Eurostat statistical data can be observed). The data show that Poland overuses this instrument by issuing EAW in minor cases, sometimes even for petty crimes, yet in spite of the phenomenon being so widespread, it has attracted little academic interest – until now.

The aim of this paper is to consider what the term ‘justice’ means and which activities of the criminal justice system could be called ‘just’ and which go beyond this term (especially in a frame of the EAW system). The main question to answer is: Should every crime be pursued (even a petty one) and every person face punishment – even after years have passed and a successful and law-abiding life has been built in another country? Maybe some restrictions should be introduced to the law to prevent the abuse of justice. Another question we raise is whether EU regulations and domestic law should allow juridical authorities to decide not to transfer a person in the case of minor offences. Is the surrender of a person wanted for minor offences in contravention with the original intention behind the establishment of the EAW and does it violate the idea of justice?

In this paper we attempt to answer these questions. We start with the presentation of legal provisions on the EU level and our understanding of them, using mostly the literature and explanations provided by the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) in its judgments. Here we focus our attention on the most important elements of the EAW procedure: principles of mutual trust and mutual recognition, followed by problems of potential infringement of fundamental rights and checks of proportionality in the procedure of issuing and executing an EAW. Then we briefly explain Poland’s implementation of the Framework Decision. The most important element for us is the practical application of these provisions, though, especially in Poland. We discuss it against the backdrop of other member states using statistical data – from Eurostat and the Polish Ministry of Justice. They are complemented by the main findings from empirical research that has been conducted in Poland so far in that area. This allows us to see a real person and sometimes the real harm behind laws and numbers and to further problematise them. The topic on which we mainly focus in the next chapter is the examination of the effectiveness of the EAW procedure vis-à-vis the protection of human rights. This is followed by a theoretical investigation into the sense of membership, justice and punishment. We present this in the reverse order to that usually presented in academic papers because, in our opinion, the theoretical reflection towards the end of this analysis brings even more in-depth understanding and discussion of the practical application of the EAW.

The legal framework of the EAW and its fundamental principles

The aim of establishing the Framework Decision 2002/584/JHA was to streamline procedures to do with persons who try to escape responsibility for crimes committed by fleeing to another EU member state. The Decision accounts for two such cases:

- the surrender of persons who have been ordered to serve a custodial sentence but who failed to do so, having fled from justice to the territory of another member state and

- the surrender of persons suspected of having committed an offence, who are being prosecuted for offences which are punishable by a custodial sentence for a minimum period of 12 months.

In order for the surrender of the above persons to take place, the rule of double criminality must be obeyed – i.e. the act for which the person was sentenced or is suspected of having committed must be criminalised both in the issuing and the executing member state (Löber 2017: 42). The rule does not apply to offences listed in Art. 2 Para. 2 of the Decision (such as, for instance, the trafficking in human beings, narcotics or weapons and murder, rape, corruption, money laundering etc.). The reason behind the move was the desire to tighten cooperation vis-à-vis prosecuting international crime, including terrorism and particularly serious crimes. Abandoning the verification of the double criminality of the act in these cases significantly speeds up the transferring procedure (Löber 2017: 39–41).

Principles of mutual recognition and mutual trust

For member states to be able to cooperate within the EAW framework, it is crucial that they follow two principles: the principle of mutual recognition (of judgements) and mutual trust (Hofmański, Górski, Sakowicz and Szumiło-Kulczycka 2008: 27; Królak, Dzialuk and Michalczuk 2006: 400). The consequence of their adoption is the assumption that member states are in principle obliged to execute EAWs issued by other member states. The rules are closely linked – mutual trust is a condition for mutual recognition.

The rule of mutual trust requires that individual member states not only accept others’ legal orders but also the validity of judgements issued by domestic courts (Hofmański et al. 2008: 27; Klimek 2015: 19). It presumes that the authorities of one member state would trust that the decision made by the judicial authority of another member state is legal (Aranyosi and Căldăraru, C-404/V5 and C-659/15, para. 79; Lanigan, C-237/15 PPU, para. 36). Hence, the refusal to execute an EAW is technically only possible within the boundaries set by the provision of the Framework Decision (Klimek 2015: 69; Schallmoser 2014: 159) while the CJEU deemed the remaining exceptions as unacceptable as a matter of principle (albeit with several caveats, as discussed below) (Aranyosi and Căldăraru, para. 80; Lanigan, para. 36). The implementation of the Framework Decision in various member states has revealed, however, that unconditional compliance with the principle of mutual recognition engenders considerable challenges, especially when it concerns the protection of fundamental rights (Böse 2015: 136).

To guarantee an appropriate level of protection of fundamental rights, the Framework Decision requires that an EAW be issued by a judicial authority. However, ‘implementation of the principle of mutual recognition means that each national judicial authority should ipso facto recognise requests for the surrender of a person made by the judicial authority of another member state with a minimum of formalities’.1 This raises the question of which institution should be recognised as a ‘judicial authority’. Initially that term encompassed every authority in the system of a member state that had the competence to issue an EAW – i.e. it applied not only to courts but also to prosecution services. The problem is that, in some countries, the prosecution services are treated as a part of the Executive. This leads to complications when the competence of issuing EAWs is exercised by an authority that does not have the hallmarks of independence and impartiality (Thomas 2013: 586). Recently, the CJEU have stated that, because issuing an EAW undermines the right to liberty of a person, it requires effective juridical protection on at least one of two levels: the issuing of the EAW or its execution (Bob-Dogi, C-241/15, para. 56). This means that the issuing judicial authority must be capable of exercising its responsibilities objectively. In some cases, as with the German Prosecution Services, the prosecution, being a part of the Executive, is specified as an ‘external’, non-juridical power in criminal procedure. The problem here lies in the perceived potential influence of politicians on that authority and their ability to issue instructions with the effect of limiting the impartiality and independence of the public prosecutor’s office (OG and PL, joint cases C-508/18 and C-82/19 PPU, para. 76). In this case, the Prosecution Service is, as the CJEU stated, not able to exercise its responsibility objectively. So, it cannot be treated as a ‘juridical authority’ and, as a consequence, cannot have competence to issue an EAW, because of the lack of an appropriate level of human rights protection.

To sum up, mutual recognition requires not only respect for material fundamental rights but also that proceedings should guarantee the effective control of its compliance with human rights. In one of its recent judgements, the CJEU further specified that ‘the public prosecutor of a member state who, although he or she participates in the administration of justice, may receive in exercising his or her decision-making power an instruction in a specific case from the executive, does not constitute an “executing judicial authority” within the meaning of those provisions’ (Openbaar Ministerie, C-510/19, para. 70; see also OG and PL, joint cases C-508/18 and C-82/19 PPU, para. 90).

The principle of mutual recognition allows for judgements made in one member state to be accepted in the legal order of another. Hence, the authority that issues the warrant is obliged to indicate an existing judgement, which will be enforced once the person has been surrendered as a result of the EAW (e.g. a conviction or a pre-trial detention order). Then the judicial authority in charge of executing the EAW undertakes to trust that the judgment was issued lawfully and issues a decision to implement the EAW and eventually surrender the person to the member state that is seeking the extradition. As the CJEU stated, both principles – mutual trust and mutual recognition – are the foundations for an area without internal borders created as the European area of freedom, security, and justice (ML, C-220/18 PPU, para. 49; LM, C-216/18 para. 36).

The rule of mutual trust relies on the assumption that every member state’s law (both in statute and in practice) guarantees an equivalent and equally effective protection of the fundamental rights of accused and convicted persons, which will be manifested, among other things, in the possibility to appeal against the decision of the court by questioning the legality of the legal proceedings behind the decision to issue the EAW (Böse 2015: 136; Melloni, C-399/11, para. 63 and 50; Dorobantu, C-128/18, para. 79; Marguery 2016: 945; Mitsilegas 2016: 24). Moreover, the principle of mutual trust prohibits the verification of compliance with the EU law for every judicial decision issued by member states that shall be executed by another. Such procedure could only be accepted in very exceptional cases (Rizcallah 2019: 38).

The scope of the rule of mutual trust is broad and covers, at one end of the spectrum, the vertical relations between the state and the citizen and, at the other, the functioning of legal systems, the organisation of the country’s authorities and the implementation of the rule of law, as well as trust in the efficiency of the implementation of the specific legal measures to which an individual is entitled and which ensure effective legal protection (Statkiewicz 2014: 36–37). In other words, trust should refer to the appropriate axiological and legal law-making process, as well as its execution in every EU state (Hofmański et al. 2008: 27; Marguery 2016: 946–947). What this means is that trust includes not only the fact that their law meets the formal standards of upholding the rule of law in a democratic country but also that its legislators will respect the basic principles guiding the observance of fundamental rights.

Moreover, EU states trust one another that their law is exercised in an appropriate manner and ensures an equal level of respect for and protection of fundamental rights (LM C-216/18 PPU para. 35; Hofmański et al. 2008: 27). Thus, the guarantor of judicial cooperation with regard to criminal cases is predicated on the assumption that every member state guarantees respect for individual rights, in accordance with standards adopted at the EU level, as well as trust that all member states abide by EU legislation and ensure its effective execution (Aranyosi and Căldăraru, para. 78). The trust is not only limited to issues pertaining strictly to cooperation when executing decisions issued by other countries – it also assumes that the EAW will not be abused by member states in order to realise goals for which the instrument was not intended and which would be in contravention of EU legislation and the principle of subsidiarity outlined in Art. 5 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

Protection of fundamental rights

An important problem that came to light when implementing the EAW in individual member states was the issue of ensuring the fundamental rights and freedoms of individuals. Traditionally, it has been recognised that the lack of a guarantee of respect for the rights of a prosecuted person is an obstacle to extradition. However, the content of the Framework Decision does not imply the need to examine this prerequisite under the EAW, as any control of the level of protection of fundamental rights would call into question the mutual trust of the member states (Hofmański et al. 2008: 160–164; Marguery 2016: 949).2 However, the question arises as to whether the suspicion of a violation of fundamental rights could (or perhaps should) justify the non-execution of the EAW and when such control should be carried out / exerted.

Analysing the CJEU’s case law, Jan Löber considered that the judicial authorities executing the EAW were not able to examine the premises that go beyond what is explicitly stated in the content of the Framework Decision and cannot refuse the execution of the EAW (Löber 2017: 155–156; see also Schallmoser 2014: 136). However, it seems that, in the light of recent CJEU judgments, this approach has lost its relevance. The Court referred to this issue in the joined cases of Aranyosi and Căldăraru. The proceeding’s main goal was to check whether it was permissible to execute an EAW and surrender a person when there were serious doubts about the prison conditions in the member state issuing the EAW, which may lead to violations of the rights and freedoms of the surrendered person. The CJEU pointed out that, although mutual trust between member states is one of the main principles of the Framework Decision, it is the duty of the state executing the EAW to examine whether the existing grounds that might justify the suspension of the warrant are real, specific and based on verified data (Aranyosi and Căldăraru, para. 94) as well as objective, reliable, specific and properly updated evidence (ibidem, para. 104). In principle, however, these circumstances may only lead to the EAW being postponed, not abandoned (ibidem, para. 98).

In other words, although the provisions of the Framework Decision do not explicitly provide for a refusal to enforce an EAW due to a violation of fundamental rights (although they were included as grounds for the refusal to surrender in recitals 10 and 13 of the Decision’s preamble), in specific cases the CJEU allowed the refusal to execute a warrant in the event of a real and immediate danger of violation of fundamental rights, in particular the possibility of violating the freedom from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (para. 104 in fine). As fundamental and absolute human rights, they can in no way be overruled (Marguery 2016: 953). Thus, the CJEU paved the way to extending the catalogue of reasons for refusing to execute an EAW by other, exceptional situations not explicitly defined in the content of the Framework Decision. However, they must result from the principles of EU law. The reason why the CJEU allowed this exception may also be the fact that the offences behind the issuing of the EAW in both cases were fairly trivial (Ouwerkerk 2018: 106) while the possible violation concerned such a fundamental right as the protection from inhuman treatment in detention. The literature also acknowledges that, in failing to provide for the possibility of refusing to execute the EAW in the event of a threat of violation of individual rights, the European legislator has, in fact, outsourced the protection of fundamental rights from the European to the national level (Schallmoser 2014: 149).

To conclude, the judicial authority in charge of the application of this measure should weigh up whether the use of the EAW is justified, not only normatively but also axiologically, also taking into account the reasons for the Framework Decision and the general principles underlying EU law, such as the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. Therefore, subsequent judgments confirming this jurisprudence of the CJEU are not difficult to imagine – for example, in cases where the offence in question is relatively insignificant, many years have passed since the conviction and the offender is well integrated into another EU member state. Under such circumstances it would be worth considering whether the surrender under the EAW does not violate the offender’s right to privacy and respect for their family life (Schallmoser 2014).3

Checks of proportionality and the level of seriousness of the offences

The proportionality check is the most often understood as an additional rationale that should be verified when issuing an EAW. It is used to determine whether the circumstances of the case justify compliance with the threshold conditions for issuing the warrant and should ensure that this instrument will not be abused by member states. The purpose of the check is therefore to build trust among member states’ competent authorities and to contribute to a more efficient functioning of the EAW (EC 2017: 15).

According to the European Commission (EC), the elements verified as part of the check should include the likelihood of an actual deprivation of liberty after the surrender to the issuing member State and the interests of victims of the crime (EC 2017: 14–15). Libor Klimek (2015) states that, among the circumstances that should be considered by the state issuing the EAW, the seriousness of the offence should also be taken into account and should be analysed against the consequences that the execution of the EAW will have on the person subjected to it. The judicial authority should also consider the possibility of using measures with less interference in the rights and freedoms and less negative impact on the surrendered person (Klimek 2015: 134). The EC’s recommendations treat proportionality much in the same way. It noticed the problem of abuse of EAW in the cases of petty crimes – which admittedly fall within the scope of the application of the EAW specified by Art. 2, para. 1 of the Framework Decision – but their weight, the length of the custodial sentence or what remained of it, as well as the possibility of using alternative measures should be considered by the judicial authority before issuing the EAW (EC 2011: 7–8). However, these recommendations are not binding. Thus, the use of the proportionality check is only recommended and not strictly required by the Framework Decision’s standards (Carrera, Guild and Hernanz 2013: 18). John Thomas (2013: 587)underlined that issuing an EAW in minor cases or with respect to offences committed many years ago could lead to questioning of the very idea of mutual recognition and mutual trust principles, which are fundamental to judicial cooperation in criminal matters, especially in EAW cases.

The above considerations pertain to the EAW at its issuing stage, not during its execution. However, it seems that, in some cases, the proportionality check should indeed also be performed while the EAW is being executed. The executing authority should, in particular, take into account the seriousness of the offence (the type of act and the circumstances in which it was being committed) and relate it to the standards guaranteed by EU law for the protection of the rights and freedoms of the individual (Ouwerkerk 2018: 108). This was precisely the case for German courts which refused to execute warrants issued against persons prosecuted for acts which, in Germany, were punished with a fine only (Böse 2015: 143–144). The Advocate General, Eleanor Sharpston, in her opinion in case Radu (C-396/11), underlined that detention under provisions of Article 5(1) of the Convention cannot be arbitrary and must be carried out in good faith. In other words, it must fulfil the proportionality test (AG 2012 Opinion in Radu, para. 62).

The use of EAWs to prosecute petty offences exposes member states to high costs on the one hand (economic argument) while, on the other, obliterating the original idea behind the establishment of the EAW – i.e. the prosecution of highly dangerous crimes, especially terrorism (axiological argument). There is also a problem of whether the use of EAWs for less-serious offences is proportionate in relation to the scale of interference in the individual’s fundamental rights (pro-liberty argument) (Carrera, Guild and Hernanz 2013: 16; Schallmoser 2014: 137). This problem is particularly evident in the case of prosecution in order to execute short custodial sentences when, instead, it would be desirable to use other measures provided for by EU law (EC 2017: 15). In any case, accounting for the seriousness of the act when assessing the violation of individual rights has already been sanctioned by CJEU case law (Ouwerkerk 2018: 109). This problem has also been seen and then solved in a more recent EU instrument of international cooperation in criminal justice processes – the European Investigation Order or EIO.4 The EU legislator expressis verbis stated that an EIO should not be used in minor cases as it would be inadequate. The issuing authority is obliged to assess at the moment of issuing the order if the evidence is necessary and proportionate (para. 11 of the EIO directive’s preamble).

Implementation of the EAW in Polish law

For many years, Polish courts have resorted to the EAW to seek offenders in profoundly trivial cases. Teresa Gardocka (2011: 33, 40) believes that, from a legal point of view, using the EAW in every case was not a mistake by the courts, since the original Polish regulations of the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC) imposed on them the obligation to use this measure whenever possible. In addition, a large number of cases that could potentially be subject to EAW provisions resulted from the fact that, in practice in Poland, it is relatively easy to receive a custodial sentence of four months – the minimum threshold at which an EAW may be requested (House of Commons 2013: 8).

The status quo was additionally due to the principle of legalism adopted in Poland, which demands that almost every offence should be prosecuted by public authorities (police or prosecutor). This also applies to the obligation to use the EAW in pre-trial proceedings (although not in executive proceedings in the case of the execution of a custodial sentence). Naturally, such a solution was uneconomical and unreasonable, especially when considering the mere cost of police convoys shouldered by the issuing state in order to bring in such individuals (Gardocka 2011: 38). In the light of these facts and taking into account the costs, the above provisions5 were amended in 2013, limiting the obligation to use the EAW for minor offences (Janicz 2018; Świecki 2019).

Current Polish regulations on the issuing of the EAW emphasise two elements. First, the use of the EAW is not mandatory but optional – the court may or may not issue a warrant (Art. 607a CPC). In addition, this warrant can only be issued if it is in the interest of justice (Art. 607b CPC). At the stage of assessing the interest of justice, the court should consider the following criteria: the seriousness of the offence, the possibility of detaining the suspect and the probable penalty that may be imposed on the person, ensuring effective protection of society and regard for the interests of the victims of the crime. Finally, the court should assess whether the use of the EAW is justified in a given case (Świecki 2019) and whether other measures provided for by the European law (EC 2017: 15–16) can be applied. In some cases, it seems more advisable to request that the offender serve a custodial sentence in the country where they currently reside, and their prospects of social rehabilitation are greater (EC 2017: 16–17). In other words, it should be assumed that the above provisions are to implement the principle of proportionality set out in the Framework Decision (Janicz 2018).

Polish regulations also provide for an obligatory refusal to execute an EAW if it could lead to a violation of human rights and freedoms (Article 607p § 1 point 5 CPC). While, until recently, this solution may have raised some doubts as to its compliance with EU law, the more recent CJEU case law, as already mentioned, recognises the unique possibility of refusing to implement an EAW on such grounds, although it should be interpreted narrowly and in accordance with the current case law of both domestic courts and the CJEU (Świecki 2019).

Practice of the EAW by Polish authorities

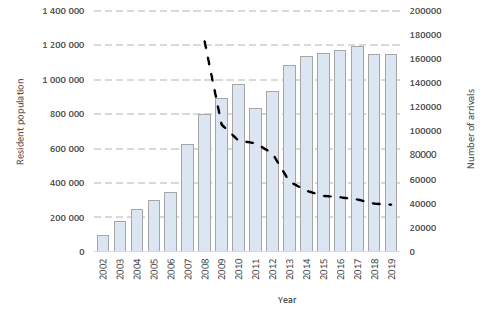

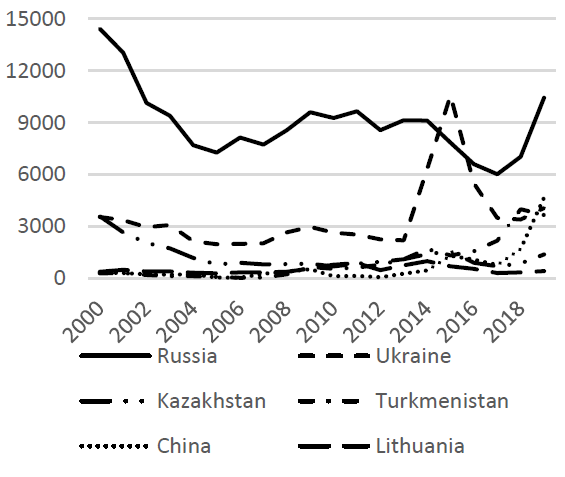

According to European statistical data, Poland was the leader with respect to the number of EAWs issued between the years 2005 and 2013. During this period, all member states of the European Union issued a total of 99,841 warrants, with varied activity by individual countries in this regard. The number of EAWs issued in different years also fluctuated considerably between 7,100 and 15,200. The analysis of statistical data reveals two trends – a twofold increase in EAWs issued by EU member states between 2005 and 2009 and a systematic decline after 2010. Over the period 2005–2013, over half of all EAWs were issued by three countries only – Poland, Germany and France (cf. Figure 1). However, while the number of warrants issued by France and Germany stood at 10,000 and 14,500, respectively, Poland issued 31,000 warrants, which constituted 31 per cent of all the EAWs issued in that period in the EU. In other countries, the number of warrants issued was far below the 10,000 threshold (EC 2019; EP 2014).

Analysis of the practice of using EAWs in subsequent years allows a certain change to be observed. For example, in 2017, EU member states issued a total of 17,491 warrants. Although, as in previous years, these warrants were the most often issued by Poland and Germany, the share of both countries was similar – it stood at 13.9 and 14.9 per cent, respectively. This means that the significant disparities between them, still visible in the years 2005–2013, had levelled out. Moreover, Germany overtook Poland in the number of EAWs issued (EC 2019).6

Figure 1. EAWs issued by EU member states between 2005–2013 (in thousands)

Source: Own calculations based on the data (EP 2014).

The practice of countries executing EAWs varies. Statistical data show that, by far, the issuing of a warrant does not always end with the successful surrender of the requested person. In the years 2005–2013, the EAW across the entire EU was only effective in 26.3 per cent of cases (cf. Figure 2). However, these numbers increased significantly, to reach 38 per cent by 2017. In the case of Poland, these indicators reached the values of 21 and 56 per cent respectively. Against the background of all countries in the years 2005–2013, Germany achieved the highest effectiveness – 39 per cent (which, in 2017, reached 47 per cent). The territorial proximity of the member states to which German authorities primarily issued EAWs may have played a part in this phenomenon – more than half of them were directed to neighbouring countries. It can be assumed that common national borders also facilitate cooperation with regard to the implementation of EAWs (Carrera, Guild and Hernanz 2013: 14). It is also worth noting that France – the third country in terms of the number of EAWs issued in the years 2005–2013 – achieved an effectiveness similar to that of Poland, i.e. 26 per cent. High EAW implementation was visible in the countries that issued the least number of warrants in 2005–2013 – such as Ireland (60 per cent efficiency), Finland (50 per cent), Denmark (50 per cent) and Luxembourg (50 per cent).

Figure 2. Efficiency of EAWs issued by EU member states between 2005–2013 (per cent)

Source: Own calculations based on the data (EP 2014).

Since the data at the EU level are incomplete, those collected by the Polish Ministry of Justice for the years 2006–2018 were also analysed (MoJ 2019). Based on the results, at least two hypotheses can be proposed. First, the change in the number of EAWs issued in Poland is in line with the European trend. The number had been increasing until 2009, after which it was followed by a decrease in the years 2010–2014 and a further and current stabilisation at the level of 2,000 to 2,500 warrants per year (see Figure 3). Secondly, the number of requests for an EAW from prosecutors decreased significantly. This may have resulted from changes in Polish law introduced in 2010 regarding the authority permitted to submit a request for a warrant. The prosecutor’s request is only necessary at the pre-trial phase while, during a trial and in post-trial phases only, the court may issue a warrant ex officio or at the request of another court (Perkowska and Jurgielewicz 2014: 86). The changes in the regulations were the result of the mounting criticism that Poland faced from other EU countries, as well as the tightening cooperation between lawyers from various countries on the functioning of the EAW (HFHR 2018: 17, Jacyna 2018: 37–38). In addition, the system for collecting statistical data on the EAW had changed (Gardocka 2011: 13).

As for the member states to which Poland directed warrants, it comes as little surprise that these were primarily countries where Poles migrate the most (Gardocka 2011: 14). The data from Statistics Poland (CSO) shows that since Poland’s accession to the EU over a million of Poles (and over 2 million since 2018) stay in other EU countries for more than three months during a year (of whom over 80 per cent live abroad for at least a year) (CSO 2018). The UK and Germany are the most popular migration destinations (Okólski and Salt 2014; Garapich, Grabowska, and Jaźwińska 2018) – in 2017, 793,000 Poles lived in the former, and 703,000 in the latter. The Netherlands (120,000), Ireland (112,000) and Italy (92,000) (CSO 2018) occupied the next positions on the list. These countries were the most frequent recipients of EAWs issued by Poland in the years

2004–2017. More than half of all warrants issued were sent to the United Kingdom7 (31.6 per cent) and Germany (24.6 per cent), followed by the Netherlands, Ireland and Italy (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. EAWs issued by Poland to EU member states between 2006 and 2018

Source: Own calculations based on data (MoJ 2019).

Figure 4. Member states which received EAWs from Poland between 2004 and 2017

Source: Own calculations based on data (MoJ 2019).

As mentioned, the success rate of EAWs was measured by the number of people who were surrendered to Poland. For warrants issued by Polish courts in the years 2004 to 2017, this figure stood at 66.5 per cent, although there were significant differences between countries (e.g. 79.6 per cent for the UK, 67.1 for Germany and 56.8 for the Netherlands). Additionally, the analysis of statistical data shows that the percentage of executed warrants increased from year to year – from just a few per cent to over 90 per cent. This increase in effectiveness translated into the number of people who were incarcerated in Polish prisons as a result of EAWs issued against them (1,692 such individuals in November 2019). Their number is steadily growing – if we compare just the years 2018 and 2019, the population recorded an increase of 217 people (CZSW 2018, 2019).

Although the EAW execution rate was highest for the UK, Poland also received the most refusals from British courts, mainly due to the fact that the number of warrants addressed to the UK was the highest. The reasons for refusals were varied and included violation of the principle of proportionality, an insufficient procedure for the protection of the health of the offender and poor-quality opinions from court experts in criminal proceedings (HFHR 2018: 33). It is also worth recalling that, in March 2018, the reason for the refusal to surrender a requested person to Poland, as indicated by the Irish High Court, was the court’s concerns regarding the independence of the Polish judiciary.8 In the opinion of the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (HFHR), poor conditions in Polish prisons – such as overcrowding, a lack of access to adequate medical care or the treatment of prisoners with disabilities – may in the future be a reason for refusal by other member states to surrender following warrants issued by Poland (HFHR 2018: 36–49). The effectiveness of the EAW should also be evaluated taking into account the time that passes between the issue of the EAW and the surrender of the person – which takes 11 months on average (HFHR 2018: 29).

Worthy of a reminder, too, is the fact that Poland receives EAWs from other EU states. Between 2004 and 2017, there were 3,680 such warrants (i.e. nearly five times fewer than Poland issued to other countries). In 2,709 cases (or 73.6 per cent), the Polish courts accepted the warrant and agreed to transfer the requested person. During this period, most EAWs came from Germany (2,125 – more than half), followed by Austria (203), Italy (138) and the UK (124) (HFHR 2018:18–19).

Effectiveness versus human rights

As a legal instrument, the EAW is rarely a subject of empirical research, especially in criminology. Only two studies have been carried out thus far in Poland. The first, in 2011, by the Institute of Justice, included an examination of court files in which Polish judicial authorities issued EAWs – 198 cases from 2008 and 105 from 2011 were covered (Gardocka 2011). The second study was conducted by the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights and covered 42 court cases in which the EAW was issued in the period 2012–2016. The results and conclusions of both of these studies are convergent.

People requested by Poland via the EAW are mainly men with Polish citizenship (93 per cent of offenders) who committed crimes against property (Gardocka 2011: 30; HFHR 2018: 23). The offenders are sought primarily at the stage of post-trial proceedings – in approximately 70 per cent of cases the EAW is issued to execute a custodial sentence (Gardocka 2011: 25; HFHR 2018: 24).

A significant problem is that the EAW allows countries to seek transfers related to old offences – in some cases they were related to acts committed back in the 1990s (in the most extreme case in 1993). Hence, the average time between committing a crime and surrender under the EAW was extremely long, amounting to some nine years (and, in one of the examined cases, 19 years). A certain justification for this considerably long period spanning the act and the execution of the EAW may be the long waiting time for the judgment issued in Poland to become final. In cases examined by the HFHR, the average time from a person committing the act to the issue of the judgment by the court of first instance was 97 months – i.e. approximately eight years (a maximum of 267 months) (HFHR 2018: 26–29). On the other hand, as the statistics of the Ministry of Justice show, the average duration of criminal court proceedings is 7.7 months for regional courts and 3.3 months for district courts (MoJ 2017: 23–24).9

All things considered, the average time between issuing the warrant and surrendering the offender to Poland was only 11 months, which shows a quite high efficiency in prosecuting offenders using the EAW (HFHR 2018: 26–29). This may be the result of the practice of law enforcement agents in countries of residence that target citizens from CEE countries. This is the case for the Netherlands, for example, where Poles, Bulgarians and Romanians are subject to much more extensive surveillance by law enforcement agents – because of prejudice and the biased belief of the law enforcement that they are more heavily involved in criminal activities, representatives of CEE nationalities are significantly more often stopped and searched by police officers. The practice could be dubbed as both national and class/economic profiling at the same time, as the targeted individuals from CEE are considerably poorer than nationals of the ‘old’ EU countries (Brouwer, van der Woude and van der Leun 2018). Hence, there may be a much higher probability that persons with EAWs issued against them will be quickly identified abroad.

The long time that passes between a crime having taken place and the execution of an EAW raises many problems. During this period, people’s lives change, often significantly. As a result, the reasons for punishment applied to a given person should be reconsidered, as they could have already been largely achieved. Important life decisions are also made as time passes, such as those related to travelling abroad and settling down in another country. Mobility and moving to other places often lead to people learning too late or even never learning at all about the next stages of the criminal proceedings that are being conducted against them – they no longer have an address in Poland and their families do not always notify them about letters from court. This causes serious problems, including convictions in absentia, when the accused persons cannot defend their case in court (Fair Trials 2018: 16; InAbsentiEAW, n.d.). It is also noteworthy that Polish regulations do not anticipate or allow for correspondence with a person residing abroad. Thus, a person who lives permanently in another EU country will not receive court letters to their foreign home address, unless they appoint a representative in Poland to whom can be delivered letters from the court, a fact about which most people do not know, while some may have trouble finding such a trustworthy individual. The lack of a Polish address does not, however, stop the judicial machine, which continues to grind, exercising the legal presumption of delivery of correspondence (HFHR 2018: 25–26). Therefore, for some people, their arrest on the basis of an EAW for the purpose of serving a sentence may come as a big surprise.

After emigrating abroad, many people lose touch with or sever ties with Poland – if they ever had them in the first place, that is. The latter situation occurred in one of the cases examined by the HFHR, when the offender was sent to Poland from France 19 years after committing a crime, under the EAW request. During his entire life he had spent only a few years in Poland where, as a teenager, he committed several burglaries. For most of his life, however, he lived in France, alongside his entire family and friends (HFHR 2018: 27). A similar picture emerges from Agnieszka Martynowicz’s (2018) research with Poles imprisoned in Northern Ireland. The people she surveyed, who were to be sent back as part of the EAW, emphasised their relationship with Northern Ireland, not Poland, a relationship which had been years in the making. For them and their families, it was the UK that had become the new homeland. One respondent declared, for instance, that he had not been to Poland for nine years. Hence, sending such people to Poland within the EAW causes them to break family ties. Another crucial problem pointed out by those at risk of extradition under the EAW was the threat to the general well-being of their family caused by their imprisonment and the consequent loss of a livelihood. This obviously resulted in a significant deterioration in the finances of the said family, including its impact on the children. In such circumstances many of the respondents focused all their efforts on trying to convince the British court to refuse the implementation of the EAW due to their (and their families’) long and stable relationship with the new state (the UK, of which Northern Ireland is a part) and settling in the new community. Uprooting them from this environment in such an abrupt manner constituted, in their opinion, a violation of their right to a private and family life (Martynowicz 2018: 281–282).

The above problems become even more pronounced when we realise which category of people are requested by Poland through the EAW and the crimes of which they are accused of or sentenced for. It will transpire that we are not dealing with serious criminals but mainly with people who committed minor offences. In 80 per cent of the cases examined by the HFHR, the criminal court imposed a sentence not exceeding two years, including cases where the sentence was accompanied by the conditional suspension of its execution (HFHR 2018: 23). Teresa Gardocka’s earlier research shows similar conclusions – 80 per cent of the cases in which the EAW was issued concerned crimes against property (such as theft and fraud10), the non-payment of child support, crimes against transportation safety, crimes against documents (most probably forging or altering documents) or crimes related to drugs – mainly the possession of a small amount of drugs often by people addicted to them (Gardocka 2011: 23-24, 28). EAWs were also used to prosecute people who, for example, stole a crate of beer and, although they admittedly used violence to commit the crime, it was only pushing a store employee in order to get hold of the crate. Other offences were that the accused stole 850 PLN (190 euros) from an open apartment, broke into a car with the intention to take the things from inside but failed to do so, as there was nothing to take, used a fake car registration certificate, smoked marijuana, rode a bicycle under the influence of alcohol or stole 10 pens worth 700 PLN (155 euros) or a mobile phone (Gardocka 2011: 34–39; HFHR 2018: 28–32). Such examples could be multiplied ad infinitum. It is clear that the huge costs associated with implementing the EAW, such as the transport of people or the translation of documents, may not always be proportionate to the ‘interests of justice’ which they are supposed to serve (Perkowska and Jurgielewicz 2014).

The most serious offenders constitute only a small percentage of all those requested under the EAW. Unfortunately, this is not only specific to Poland but applies to many countries (Fair Trials 2018: 10–11). In 2012 and 2013, warrants issued in all the European Union countries covered only 25 rapes, 24 murders and 11 kidnappings (EP 2014). In 2017, out of nearly 18,000 warrants in total, only 241 were issued to perpetrators of terrorist offences (EC 2019). In Poland in 2008, only five warrants concerned serious crimes against a person, including a murder. In 2011, these numbers changed very slightly to include seven crimes against a person and four killings (Gardocka 2011: 24, 28). These data raise the question of whether the goal set for the EAW as a legal instrument has been achieved. Should provisions developed almost two decades ago not be modified in view of these findings?

The EAW and the sense of membership, justice and just punishment

Having discussed both the legal background and the Polish practice of applying the EAW, this section will focus on the more fundamental issue of the goals of the criminal justice system in general (at both national and EU levels).

Thinking about the EU as a community and trying to embed the criminal justice system into it as a common instrument, we should start from the standpoint that ‘community is realised by shared obligations and duties’ (Lemke 2014: 73). This should also encompass common and shared responsibility for individuals who break the law – regardless of whether it happened in the country of origin or in the country of residence. Community is understood here on at least two levels. The first is the European level which, within the EU, creates a community of states and their societies. It assumes therefore the obligation and duty of states (governments) to help and support each other, which could lead to a country taking over the responsibility for prosecuting and punishing an individual who commits a crime. This arrangement works both ways – it enables the surrender of a person who committed a crime and is trying to flee from justice to the country which then requests their presence before the court of justice or that they serve their time in prison (here the EAW serves as a perfect tool). However, it should also work the other way around – to ensure that justice is delivered with the guarantee, nevertheless, that the procedure is right and just and should be performed in the country of residence. Especially in the case of a person who was convicted and should serve some time in prison. Transferring them to the country of origin could be unjust if they have spent a significant amount of time in the country of current residence, have built their life there (including family ties) and developed connections with the local community.11

Here we come to the second meaning of the term ‘community’ – realised on a more local level – as a relationship between members of a certain group who live on the same territory and as obligations towards those members by their government irrespective of whether they have formal citizenship of the country or not. They are thus de facto citizens (Thym 2014) who hold ‘social membership’ – to use the term coined by Joseph Carens (2013). This membership works both ways – individuals/members should benefit the community but, at the same time, should be entitled to the protection of that community, even if they committed a crime, as these ties are for better or for worse and the community cannot excuse itself from its obligations toward a member.

Nonetheless, the question of when an individual becomes a member and under what circumstances still stands. According to Carens (2013: 104, 165), the only condition should be the length of residence and no other factors should be taken into account in this matter. The length that Carens considers appropriate is five years of residence in a particular country. In the jurisprudence of the EctHR, the bar was set higher, however. In the judgement of Üner v. the Netherlands, the Court indicated that a person’s mere presence in the country is not enough and the applicant should prove ‘the solidity of [his/her] social, cultural and family ties with the host country’ (EctHR 2006, para. 58). Only meeting these criteria (though not yet specifically defined in the ECtHR’s jurisprudence) allows a person not to be deported from the country of residence, even if they committed a serious crime (like manslaughter in the case of Üner).

On the other hand, we could find theories that take the opposite approach. The very idea of exclusion from the community is a pivotal element of Günter Jakobs’ theory of ‘enemy criminal law’ (Díez 2008) or ‘enemy penology’ (Krasmann 2007), as the German term Feindstrafrecht is translated into English. For Jakobs, any person who has committed a crime, especially a serious one, or if the person is a persistent offender, then he or she is no longer a member of the community. By breaking the law, they have broken the Rousseauian idea of social contract and therefore, as with non-members, no rights or protection apply to that individual. In other words, the community no longer has any obligations towards that person. In addition, the community has the right to protect itself from such an individual and therefore can apply procedures and take actions that would be unacceptable if the accused were still considered as a member. The essence of Jakobs’ theory is to create a legal outcast, a banned man [sic], who can be sacrificed (Agamben 1998) in the name of security and the protection of the community. One form of such protection is expulsion.

In his theory, Jakobs writes about citizens who can be deprived of their rights. However, when we think of immigrants, we generally refer to non-members (disregarding briefly Carens’ humanitarian idea of social membership) – non-citizens who never had any rights in the first place, so do not need to be stripped of them (Stumpf 2006; Weber and McCulloch 2018). In this context, it is worth mentioning that, when we discuss the EAW, we are mostly talking about EU nationals. They hold ‘European citizenship’ so their rights and general position in other member states are much higher compared to if they were merely a ‘regular immigrant’. So, on a scale created by Tomas Hammar, these individuals are somewhere between the denizen and the citizen (Hammar 2003). This is yet another argument for increasing the level of protection against their forced removal under any circumstances from the country of residence (even using the EAW as an instrument), which should be reflected in the law.

The other no less important question when assessing the practical implementation of the EAW is how it serves as an instrument intended to deliver justice. Justice is a very broad concept that is difficult to define and has different meanings for almost everyone. In his influential book, A Theory of Justice, John Rawls (2005) proposed to understand justice as fairness. He built his theory on the concept of social contract. According to him, justice is embedded in the idea of equality among members and assumes mutual obligations and duties between all members. This theory is very idealistic (or even utopian) and assumes that, in an ideal society of equality and fairness, the reasons behind crimes will disappear, rendering the punishment obsolete. Because ‘[c]riminality does not surface in a well ordered regime’, Rawls wagers that citizens governed by relatively just institutions will acquire a ‘corresponding sense of justice’ (Honig 1993: 110). Yet he accepts some forms of punishment for criminal behaviour in exceptional cases, where immoral individuals break the rules of the ideal community. David Miller (1991) shares a similar understanding of justice. In his theory, justice is built on three pillars: needs, equality and just deserts. The latter term means that individuals should be rewarded based only on their own activities and what they deserve and that this reward should be suited to them (Miller 1991). Even though the author focuses on rewards only, this concept could be applied to punishment accordingly. The idea of proportionality is contained here, although it is not mentioned explicitly. So, against this backdrop, built especially on the combination of the principles of proportionality and equality, we can try to understand what ‘just punishment’ means.

In the very sense of punishment is embedded the idea of pain (Walzer 1983: 269). This pain differs and depends on:

- the type of punishment; while the biggest academic furore is attributed to a description of the most severe form of punishment and pain that is caused, i.e. by imprisonment (see Crewe 2009; Sykes 1958), non-custodial punishments also bring pain, yet of different nature (Durnescu 2011)and

- the personal perception of a perpetrator who was punished: their individual life experiences, moral values or understanding of what the punishment is and what its purpose is (van Ginneken and Hayes 2017).

To deliver justice (or just punishment) to an individual, a judge should take all of these aspects into consideration and measure the appropriate proportion of pain needed to ensure that he or she got what they deserved. The grounds for that measurement are mostly based on the seriousness of the crime committed and the personal characteristics of the perpetrator. It is in line with the sense of justice discussed above. Not only should the judge count the direct effects of punishment and the direct pain it causes but should consider the oblique pains as well, those indirectly ‘intended pains arising from either the general consequences of conviction or punishment, or the specific known circumstances of the penal subject’ (Hayes 2018: 251).

This rule should be applied not only to the sentencing process during the trial but also to every intervention that is undertaken by the criminal justice system towards a convicted individual, including issuing EAWs and surrendering the person subject of this request. In this sense and in our opinion every judicial authority should check whether any action taken within the frame of an EAW puts an unjust amount of pain on an individual. If it does, it should be stopped or mitigated by other solutions. Otherwise, the fundamental rights of the person would be under threat. The consequences, to that person, of his or her surrender to the EAW should be therefore understood as a form of specific oblique pains that need to be investigated by the judge (especially the one deciding on the transfer to the country that issued a warrant) based on the individual characteristic of the transferee, the crimes they committed and their level of integration in the country of residence.

Nevertheless, the idea of justice presumes that it is delivered not only to the individual guilty of wrongdoing but also to the society. This means that members of the community should not be left under the impression that someone managed to flee from justice without facing any consequences or that the consequences were inappropriate or too lenient. Another quite important element of justice is deterring others from breaking the rules (Walzer 1983: 269) while, at the same time, preventing a perpetrator from continuing their criminal activities (Zimring and Hawkins 1973). Taking into consideration both these aspects and the problems presented above on the additional and severe pain of transferring a person under the EAW, a reformed system should be proposed which would allow at least some people requested by the EAW to serve their sentences in the country of residence.

Conclusions

In this paper we are not calling for the abolishment of the whole system of EAWs. Rather, in our opinion, several amendments should be introduced to reform it. The main focus should be put on an increase of the individualisation of this process. At both stages – especially where an EAW is issued by one member state but executed by another (which usually implies an agreement to transfer a particular person to the issuing country) – the character of the crime committed and of the person to be transferred should be taken into consideration. The former mostly by the judicial authority issuing the warrant and the latter by the one that executes it. We are perfectly aware that the very idea of EAWs is rooted in the automation of this process in order to speed up and simplify it as far as possible. However, in practice we see that this mechanism is too simplistic and leads to violations of human rights. From this aspect alone it should be corrected.12

Our idea of introducing an element of individualisation, especially at the issuing stage, derives from the notion of membership. This is why we argue that, in the process of assessing an individual, the time they spent in the country of residence must be considered, especially their ties with the country and its society. If the person is well integrated and has developed social connections, they should be treated as a member of this society (Carens 2013); this is why they should not be expelled to another country (incorrectly and misleadingly called the ‘home’ country – which, for a number of people, is not home anymore) in order to serve their time in prison there. The imprisonment of this person should be possible in the country of residence (which has de facto become the home country). The possibility of the executing judiciary authority being able to change the sentence should also be introduced. Even if only in exceptional cases, this should be possible when a long period of time has passed between the date of committing the crime and the date when a person was arrested under the EAW. These new instruments could serve to mitigate the pain of punishment, which should be proportionate to the crime committed (Hayes 2018).

In a situation where a person is pursued by an EAW and facing criminal charges, they could be transferred for a limited period of time in order to complete the criminal process but, afterwards, they should be entitled to claim the right to serve the sentence in the country of residence. The other possibility in this case is to use other legal instruments of mutual cooperation in the criminal justice system between member states to prosecute or to sentence a person (EC 2017: 15–16).

The new system should seek a balance between the two faces of justice and two of its values. On the one hand, it should protect and prohibit practices of escaping justice by fleeing to another country. At the same time, nevertheless, it should not bring additional and unjust pain to people who have successfully rebuilt their lives in a new country and have lived crime-free for several years. Not only is the question of unfair pain pertinent here but also that of the purpose of the punishment (which perhaps has already been achieved); both questions should be asked and answered by the judicial authorities.

Funding

Research presented in this article is part of the project ‘Experiences of Poles Deported from the UK in the Context of the Criminal Justice System’s Involvement’, financed by the National Science Centre, Poland, under Grant No. UMO-2018/30/M/HS5/00816.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the Authors.

ORCID IDs

Witold Klaus  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2306-1140

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2306-1140

Justyna Włodarczyk-Madejska  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0734-6293

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0734-6293

Dominik Wzorek  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5274-2784

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5274-2784

Notes

1 Explanatory Memorandum on the Council Framework Decision on the European arrest warrant and the surrender procedures between the member states (Official Journal 332 E, 27/11/2001 P. 0305–0319).

2 Nevertheless some legislation (including Polish) provides for the possibility of refusing to surrender a person because of the fear that their rights and freedoms will be disregarded in the country issuing the EAW. The countries concluded that the replacement of traditional extradition with the new European institution must not lead to a lowering of the level of protection of individual rights (Hofmański et al. 2008: 78–80).

3 The question remains, what should a member state do with a person who cannot be surrendered under the EAW? Should it carry out the sentence imposed on them according to the member state’s penitentiary system or should it judge the suspect independently? The CJEU will probably have to answer these questions soon (Marguery 2016: 956).

4 Directive 2014/41/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 regarding the European Investigation Order in criminal matters.

5 Act of 27 September 2013 amending the act – Code of Criminal Procedure and some other acts (Journal of Laws, item 1247, as amended). The regulations came into force on 1 July 2015.

6 These data sum up the numbers provided in the responses that were received by the EC from each member state. However, it should be mentioned that these countries were not obliged to send the data, hence they were sometimes presented in a selective manner – e.g. only for particular years. Therefore, its analysis should be approached with some reservations. Legislative changes may also have been introduced in individual countries which may have affected data recording. The data on the number of warrants issued in preparatory proceedings were established for 18 countries. At this stage there were definitely fewer warrants issued (2,960) of which France issued nearly a quarter (EC 2019).

7 After the Brexit has been finally completed no new warrants are sent to the UK and those issued previously and not yet implemented are suspended – as it was predicted by some academics (Bárd 2018; Światłowski and Nita-Światłowska 2017).

8 Minister for Justice and Equality v Celmer, [2018] IEHC 119. Online: http://www.courts.ie/Judgments.nsf/0/578DD3A9A33247A38025824F0057E747 (accessed: 5 May 2021).

9 This is the period from the date of registration of the case by the court (so exclude the prosecuting stage of the criminal proceeding) to the date of issue of the judgment by the court of the first instance (so not a final judgment as it is still open to appeal). There were shorter (up to three months) and longer proceedings (even over eight years) but the average length was calculated for all criminal cases. To compare, the disposition time (which is a measure of the time needed to resolve a case) for all criminal cases in Poland in 2016 was 95 days (CEPEJ 2018: 19; Klimczak 2020: 229).

10 For example, theft and fraud in 2012/2013 accounted for almost half of all arrests in the UK under the EAW (EP 2014).

11 See also the understanding of the principle of European solidarity presented by the Advocate General Eleonor Sharpston (although in a slightly different case on sharing responsibility for the relocation of asylum-seekers). She stated ‘[s]olidarity is the lifeblood of the European project. Through their participation in that project and their citizenship of European Union, member states and their nationals have obligations as well as benefits, duties as well as rights’ (AG 2019, para. 253).

12 Bearing in mind, however, that it should not reflect traditional extradition processes which, due to their length, are also very painful for people subjected to them (Światłowski and Nita-Światłowska 2017).

References

Agamben G. (1998). Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bárd P. (2018). The Effect of Brexit on European Arrest Warrants. CEPS Papers in Liberty and Security in Europe No. 2. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies.

Black D. (2011). Moral Time. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Böse M. (2015). Human Rights Violations and Mutual Trust: Recent Case Law on the European Arrest Warrant, in: S. Ruggeri (ed.), Human Rights in European Criminal Law, pp. 135–145. Cham, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London: Springer International.

Brouwer J., van der Woude M., van der Leun J. (2018). (Cr)Immigrant Framing in Border Areas: Decision-Making Processes of Dutch Border Police Officers. Policing and Society 28(4): 448–463.

Carens J. (2013). The Ethics of Immigration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carrera S., Guild E., Hernanz N. (2013). Europe’s Most Wanted? Recalibrating Trust in the European Arrest Warrant System. CEPS Papers in Liberty and Security in Europe No. 55. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies.

CEPEJ (2018). Revised Saturn Guidelines for Judicial Time Management (3rd revision). As adopted at the 31th plenary meeting of the CEPEJ Strasbourg, 3 and 4 December 2018. Strasbourg: European Commission for The Efficiency of Justice. Online: https://rm.coe.int/cepej-2018-20-e-cepej-saturn-guidelines-time-management-3rd-revision/16808ff3ee (accessed: 5 May 2021).

Crewe B. (2009). The Prisoner Society: Power, Adaptation and Social Life in an English Prison. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Díez C. G. J. (2008). Enemy Combatants Versus Enemy Criminal Law: An Introduction to the European Debate Regarding Enemy Criminal Law and Its Relevance to the Anglo-American Discussion on the Legal Status of Unlawful Enemy Combatants. New Criminal Law Review: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal 11(4): 529–562.

Durnescu I. (2011). Pains of Probation: Effective Practice and Human Rights. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 55(4): 530–545.

CSO (2018). Informacja o Rozmiarach i Kierunkach Czasowej Emigracji z Polski w Latach 2004–2017. Warsaw: Central Statistical Office. Online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/migracje-zagraniczne-ludn... (accessed: 5 May 2021).

CZSW (2018). Statistical Information from the General Directorate of Prison Service; Letters No BIS.0334.90.2018.AZ of 21.09.2018. Centralny Zarząd Służby Więziennej.

CZSW (2019). Statistical Information from the General Directorate of Prison Service; Letters No BIS.0334.85.2019.AZ of 20.11.2019. Centralny Zarząd Służby Więziennej.

EC (2011). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the Implementation since 2007 of the Council Framework Decision of 13 June 2002 on the European Arrest Warrant and the Surrender Procedures between Member States (COM(2011) 175 Final). Brussels: European Commission. Online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0175&from=PL (accessed: 5 May 2021).

EC (2017). Commission Notice – Handbook on How to Issue and Execute a European Arrest Warrant. Brussels: European Commission. Online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017XC1006(02)&from=PL (accessed: 5 May 2021).

EC (2019). Replies to Questionnaire on Quantitative Information on the Practical Operation of the European Arrest Warrant – Year 2017. Commission Staff Working Document. Brussels: European Commission. Online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/replies_to_questionnaire_on_q... (accessed: 5 May 2021).

EP (2014). European Arrest Warrant (EAW). At a Glance Infographic – 23/06/2014. Strasbourg: European Parliament. Online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/EPRS/140803REV1-European-Arrest-Warrant-FI... (accessed: 5 May 2021).

Fair Trials (2018). Beyond Surrender. Putting Human Rights at the Heart of the European Arrest Warrant. Fair Trials. Online: https://www.fairtrials.org/sites/default/files/publication_pdf/FT_beyond... (accessed: 5 May 2021).

Garapich M. P., Grabowska I., Jaźwińska E. (2018). Migracje Poakcesyjne z Polski, in: M. Lesińska, M. Okólski (eds), 25 Wykładów o Migracjach, pp. 208–220. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Gardocka T. (2011). Europejski Nakaz Aresztowania. Analiza Polskiej Praktyki Występowania Do Innych Państw Unii Europejskiej z Wnioskiem o Wydanie Osoby Trybem Europejskiego Nakazu Aresztowania. Warsaw: Instytut Wymiaru Sprawiedliwości.

Hammar T. (2003). Denizen and Denizenship, in: A. Kondo, C. Westin (eds), New Concepts of Citizenship: Residential/Regional Citizenship and Dual Nationality/Identity, pp. 31–56. Stockholm: Centre for Research in International Migration and Ethnic Relations (CEIFO).

Hayes D. (2018). Proximity, Pain, and State Punishment. Punishment and Society 20(2): 235–254.

HFHR (2018). Praktyka Stosowania Europejskiego Nakazu Aresztowania w Polsce Jako Państwie Wydającym. Raport Krajowy. Warsaw: Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights. Online: http://www.hfhr.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ENA_PL.pdf (accessed: 5 May 2021).

Hofmański P., Górski A., Sakowicz A., Szumiło-Kulczycka D. (2008). Europejski Nakaz Aresztowania w Teorii i Praktyce Państw Członkowskich Unii Europejskiej. Warsaw: Wolters Kluwer Polska.

Honig B. (1993). Rawls on Politics and Punishment. Political Research Quarterly 46(1): 99–125.

House of Commons (2013). Pre-Lisbon Treaty EU Police and Criminal Justice Measures: The UK’s Opt-in Decision. Ninth Report of Session 2013–14. London: House of Commons. Online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmhaff/615/615.pdf (accessed: 5 May 2021).

InAbsentiEAW (n.d.). Improving Mutual Recognition of European Arrest Warrants for the Purpose of Executing in Absentia Judgments Poland – QUESTIONNAIRE to Research Project on European Arrest Warrants Issued for the Enforcement of Sentences after In Absentia Trials. Maastricht: InAbsentiEAW Research project on European Arrest Warrants issued for the enforcement of sentences after in absentia trials. Online: https://www.inabsentieaw.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Poland.pdf (accessed: 5 May 2021).

Jacyna M. (2018). Country Report on the European Arrest Warrant. The Republic of Poland. Online: https://www.inabsentieaw.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Background-Report_in-absentia-EAW-in-the-Republic-of-Poland.pdf (accessed: 5 May 2021).

Janicz M. (2018). Art. 607b, in: K. Dudka (ed.), Kodeks Postępowania Karnego. Komentarz. Warsaw: Wolters Kluwer Polska.

Klimczak J. (2020). Wpływ Spraw do Sądów Powszechnych Polski i Wybranych Państw Unii Europejskiej w Latach 2006–2016, in: P. Ostaszewski (ed.), Efektywność Sądownictwa Powszechnego – Oceny i Analiz, pp. 209 – 272. Warsaw: Instytut Wymiaru Sprawiedliwości.

Klimek L. (2015). European Arrest Warrant. Cham, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London: Springer International.

Krasmann S. (2007). The Enemy on the Border: Critique of a Programme in Favour of a Preventive State. Punishment and Society 9(3): 301–318.

Królak S. M., Dzialuk I., Michalczuk C. (2006). Współpraca Sądowa w Unii Europejskiej. Akty Prawne, Uzasadnienia, Komentarze. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Lemke T. (2014). The Risks of Security: Liberalism, Biopolitics, and Fear, in: V. Lemm, M. Vatter (eds), The Government of Life: Foucault, Biopolitics, and Neoliberalism, pp. 59–74. New York: Fordham University Press.

Löber J. (2017). Die Ablehnung Der Vollstreckung Des Europäischen Haftbefehls: Ein Vergleich Der Gesetzlichen Grundlagen Und Praktischen Anwendung Zwischen Spanien Und Deutschland. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

Marguery T. (2016). Rebuttal of Mutual Trust and Mutual Recognition in Criminal Matters: Is ‘Exceptional’ Enough? European Papers 1(3): 943–963.

Martynowicz A. (2018). Power, Pain, Adaptations and Resistance in a ‘Foreign’ Prison: The Case of Polish Prisoners Incarcerated in Northern Ireland. Justice, Power and Resistance 2(2): 267–286.

Miller D. (1991). Recent Theories of Social Justice. British Journal of Political Science 21(3): 371–391.

Mitsilegas V. (2016). Conceptualising Mutual Trust in European Criminal Law. The Evolving Relationship Between Legal Pluralism and Rights-Based Justice in the European Union, in: E. Brouwer, D. Gerard (eds), Mapping Mutual Trust: Understanding and Framing the Role of Mutual Trust in EU Law, pp. 23–36. San Domenico di Fiesole: European University Institute.

MoJ (2017). Podstawowa Informacja z Działalności Sądów Powszechnych: I Półrocze 2017 Na Tle Poprzednich Okresów Statystycznych. Warsaw: Ministry of Justice.

MoJ (2019). Europejski Nakaz Aresztowania w Latach 2006–2018. Warsaw: Ministry of Justice. Online: https://www.isws.ms.gov.pl/pl/baza-statystyczna/opracowania-wieloletnie/download,2853,7.html (accessed: 5 May 2021).

Okólski M., Salt J. (2014). Polish Emigration to the UK after 2004: Why Did So Many Come? Central and Eastern European Migration Review 3(2): 11–37.

Ouwerkerk J. (2018). Balancing Mutual Trust and Fundamental Rights Protection in the Context of the European Arrest Warrant: What Role for the Gravity of the Underlying Offence in CJEU Case Law? European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice 26(2): 103–109.

Perkowska M., Jurgielewicz E. (2014). Analysis of the Polish Practice of Applying the European Arrest Warrant: A Legal and Statistical Perspective, in: S. Pikulski, K. Szczechowicz, M. Romańczuk-Grądzka (eds), Effectiveness of Extradition and the European Arrest Warrant, pp. 85–98. Olsztyn: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warmińsko-Mazurskiego w Olsztynie.

Rawls J. (2005). A Theory of Justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rizcallah C. (2019). The Challenges to Trust‐Based Governance in the European Union: Assessing the Use of Mutual Trust as a Driver of EU Integration. European Law Journal 25(1): 37–56.

Schallmoser N. M. (2014). The European Arrest Warrant and Fundamental Rights. European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice 22(2): 135–165.

Statkiewicz A. C. (2014). Zasada Wzajemnego Zaufania Państw Członkowskich Unii Europejskiej Jako Podstawa Budowania Europejskiej Przestrzeni Karnej. Folia Iuridica Wratislaviensis 3(1): 11–86.

Stola D. (2012). Kraj Bez Wyjścia? Migracje z Polski 1949–1989. Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN.

Stumpf J. (2006). The Crimmigration Crisis: Immigrants, Crime, and Sovereign Power. American University Law Review 56(2): 367–419.

Sykes G. M. (1958). The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Szwarc-Kuczer M. (2011). Kompetencje Unii Europejskiej w Dziedzinie Harmonizacji Prawa Karnego Materialnego. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Światłowski A., Nita-Światłowska B. (2017). Brexit and the Future of European Criminal Law – A Polish Perspective. Criminal Law Forum 28(2): 319–324.

Świecki D. (2019). Kodeks Postępowania Karnego. Tom II. Warsaw: Wolters Kluwer Polska.

Thomas J. (2013). The Principle of Mutual Recognition – Success or Failure? ERA Forum 13(4): 585–588.