Mobility and Connection to Places: Memories and Feelings about Places that Matter for CEE-Born Young People Living in Sweden

-

Author(s):Shmulyar-Gréen, OksanaMelander, CharlotteHöjer, IngridPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. 11, No. 2, 2022, pp. 119-135DOI: 10.54667/ceemr.2022.10Received:

13 June 2022

Accepted:23 November 2022

Published:1 December 2022

Views: 8212

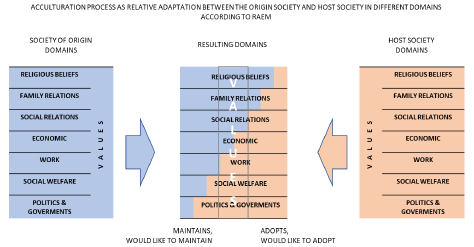

This article addresses issues of mobility and place-making among CEE-born young people who migrated from Poland and Romania to Sweden as children (up to the age of 18). Previous research on intra-EU mobility in other destinations posits this group as 1.5-generation migrants who, due to their mobility at a formative age, experience duality and in-betweenness – with specific effects on their social and familial lives. Inspired by this research, our article examines how mobility to Sweden at a young age (re)shapes young peoples’ connection to and meaning-making of places post-migration. Drawing on two-step qualitative interviews with 18 adolescents and young adults from Poland and Romania, as well as on drawings and photographs as part of the visual materials produced by the participants, the article makes two contributions. First, it integrates the scholarship on children and youth mobility, translocalism and place-making but also deepens these conceptualisations by underlining the role of memories and feelings in young people’s place-making processes. Second, the article suggests that visual methodology is a valuable tool with which to capture the embodied and the material practices of translocal place-making over time. Our findings reveal that most of these young people continue to strongly associate with places from their childhood and country of origin. For some, these places symbolise ongoing transnational practices of visits and daily communication while, for others, these are imaginary places of safety and a right place to be. The findings also highlight the importance of memories and feelings in creating transnational connectivity between the countries of origin and Sweden, as well as in developing coping strategies against the social exclusion and misrecognition which some young people may experience in their new living spaces.

Introduction

A growing volume of research focusing on the transnational mobility of middle-class youth and second-generation young migrants has highlighted the importance of place, space and localities in how young migrants transform their kinship ties and other intimate relationships, as well as the non-linearity and fluidity in these processes (e.g. Habib and Ward 2020; Haikkola 2011; Harris, Baldassar and Robertson 2020). The research on contemporary patterns of global and European family mobility has, in its turn, highlighted the diversity in childhood and young people’s lives which is driven, among other things, by their noticeable involvement in transnational family mobilities and translocal ways of life (e.g. Assmuth, Hakkarainen, Lulle and Siim 2018; Farrugia 2015; Freznoza-Flot and Nagasaka 2015).

The mobility of the young people on whom we focus here pertains to this specific context – family mobility within the EU – which, since 2004 has prompted significant numbers of migrants to seek employment and settle in another EU member state. As members of these families, children and young people born in Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries have been extensively studied as the 1.5 generation of migrants (Assmuth et al. 2018; Jørgensen 2016; Moskal 2015; Sime, Moskal and Tyrell 2020; Tyrell, Sime, Kelly and McMellon 2019). This literature broadly suggests that, compared both to their parents (as the first generation) and their younger siblings who were born in the country of destination (the second generation) the 1.5 generation of migrants occupy a unique place of ‘in-betweenness’ (Tyrell et al. 2019). Tyrell et al. (2019: 3) identify several important aspects of the position ‘in-between’, including ‘a) in-between origin and destination; b) in-between youth and adulthood; and c) in-between majority and minority culture in the host society’.

By applying the designation of 1.5 generation to the participants of this current research, we attempt to shed light on the complexity of their place-making processes, while navigating their multiple positions of being ‘in-between’. More specifically, the article examines how mobility (re)shapes the connection to and meaning-making of places post-migration, as exemplified by the experiences of adolescents and young adults born in Poland and Romania who, as children (up to the age of 18), moved to Sweden either with or after their parent(s).

We argue that the experiences of mobility and upbringing among CEE-born young people living in Sweden warrants further exploration for several reasons. Sweden is often overlooked as an empirical site in European comparative research on youth mobility (see, however, Shmulyar Gréen, Melander and Höjer 2021). Little attention has been given to the growing popularity of Sweden, since 2004, as a country where employment is possible, together with reunification and longer period of settlement for European migrants and their family members (although see Melander and Shmulyar Gréen 2018; Melander, Shmulyar Gréen and Höjer 2020; Shmulyar Gréen and Melander 2018). According to some estimations, of the nationals from EU countries residing in Sweden in the year 2020, 93,762 and 32,741 were born in Poland and Romania respectively (Delmi 2020). The large-scale outmigration from Poland and Romania to other EU countries – and to Sweden in particular – differs in several respects (see Shmulyar Gréen and Melander 2018). What is important, however, is that, in legal terms, Polish and Romanian nationals and their offspring have not been considered as migrants per se. Moreover, due to the rhetoric of free mobility and assumed ‘sameness’ (Waerdahl 2016), Polish and Romanian families and their children tend to easily ‘disappear’ in official statistics, as well as to be treated as ‘invisible’ in migration research. Statistics Sweden (SCB 2020) indicate that, in the year 2018, 9 per cent of all children under 18 years old living in Sweden were foreign-born, with Poland being the fifth most-common country of birth. For the purposes of this research, we rely on descriptive data from Statistics Sweden (SCB 2019), estimating that approximately 23,000 CEE-born young people, with Poland and Romania the most frequent countries of origin, resided in Sweden together with their families in 2018.

In this article we draw on the experiences of 18 of these young people, aged 16 to 29, who have lived in Sweden for at least four years. Common to their life trajectories is that most of them first experienced family separation due to the circular mobility of one or both parents between the home country and Sweden, followed by a few years of living at a distance from their parents and, finally, joining their parent(s) in Sweden. An analytical focus on place-making is one of the central research questions in the broader research project1 upon which this article draws and as part of which we asked young people about the everyday places (physical and virtual) through which they extend and develop meaningful relationships post-migration. Combining two-step qualitative interviews, in which – among other visual methods – we used drawings and photographs produced by the participants, the article makes two contributions. First, it integrates the scholarship on children and youth mobility, translocalism and place-making but also deepens these conceptualisations by underlining the role of memories and feelings in young people’s place-making processes. Second, the article suggests that visual methodology is a valuable tool with which to generate narratives about the embodied and material practices of translocal place-making over time.

Translocal childhoods and youths through the lens of place-making

The starting point in theorising our 1.5-generation children’s and young people’s sense of in-betweenness is the ‘mobile childhoods’ approach developed by Fresnoza-Flot and Nagasaka (2015). Through the lens of ‘mobile childhoods’, we highlight that children’s and youth’s individual experiences of mobility are embedded within at least three underlying processes – mobilities in ‘space, time and context’ (2015: 29). This conception is particularly useful to understand how young people, due to family chain mobility to Sweden, are compelled to develop connections and ties ‘across varied and multiple distances’ and spaces (2015: 28). In other words, even if their own spatial mobility has been postponed due to longer periods of separation, they may experience contextual mobility, for instance, by imagining ‘abroad’ and by extending their meaningful social relationships to other locations, connecting them to families and other people whom they care about (e.g., Haikkola 2011). Using the lenses of the ‘mobile childhoods’ approach makes us attentive to the fact that, when young people talk about their own spatial mobility as children, they describe mobility not only in space but also in time and in a number of other overlapping contexts. They experience mobility in terms of changing both the social (schooling, housing, social class) and political (citizenship rights, welfare regime) aspects of their lives and also the cultural (language) and symbolic (identity, memories) aspects (Fresnoza-Flot and Nagasaka 2015). At the same time, their current narratives reveal an emotional dislocation and longing through the young migrants’ memories of their mobility as children both in context and in time.

As a complement to the ‘mobile childhoods’ approach, we use the notion of migrant translocalism in research with children (Assmuth et al. 2018; Moskal 2015). Assmuth et al. (2018: 7) designate the notion as ‘grounded transnationality’, pointing out the ‘situatedness during mobility’ – meaning that children’s and youth’s mobilities are embodied and locally attached. The concept underlines that, while being mobile transnationally, the young people in our study leave the towns and villages where they were born and move to places where they may have family members or where their parents were able to create a livelihood prior to their children’s own mobility to Sweden. Using the concept of translocal mobility in her study, Moskal (2015) shows how migrant children and youth appropriate new places at destination and turn them into meaningful spaces through their daily routines and interactions.

Obviously, the translocal perspective on children’s and youth’s mobility makes relevant the concepts of place, space and locality/territory (Farrugia 2015; Haikkola 2011; Harris et al. 2020; Marcu 2012). The concept of place, extensively theorised in human geography and psychology (e.g. Massey 1994) and, by extension, in the sociology of mobility and belonging (e.g. Gustafson 2002), is a notion with multiple meanings, including references to the ‘immediate context, imagined places and aspirational places’ (Habib and Ward 2020: 173). The notions of space and place are interlinked, as ‘places are spaces which people have made meaningful’ (den Besten 2010: 182). In our analysis, we define places as ‘articulated moments in networks of social relations and understandings’ (Massey 1994: 67) that are stretched out ‘at all spatial scales, from the most local level to the more global’ (1994: 264). Following this line of thought, place is analysed as a dynamic entity, shaped by temporal, experiential and affective processes, where young migrants may occupy differentiated positions due to the ‘power geometries that can be traced to economic, social and cultural processes that span the globe’ (Farrugia 2015: 613). This means that, due to mobility, children and young people may gain an access to new opportunities within spaces such as education, work, free-time activities, etc.; however, ‘there are forms of exclusion and control that take place in and through space’ (2015: 617).

In our quest to understand how mobile youth construct transnational connectivity between places and spaces both prior to and post-migration and how they overcome the processes of ‘othering’ and feelings of being ‘out of place’, the notions of memory (Fox and Alldred 2019; Keightley 2010; Leyshon 2015) and emotions (den Besten 2010; Marcu 2012) are useful. The wider project upon which this article draws, underlines the importance of affective bonds in migrant children’s and youth’s everyday lives, including the ‘practices of love, care and solidarity’ (McGovern and Devine 2016: 38), which mediate their attachments to people and places (see Shmulyar Gréen et al. 2021). In this article, we call attention to the role of memory in these processes. As Marcu (2012: 207) argues, ‘different places create experiences that, at the same time, produce memories which are wrapped in feelings and that play an important role in constructing identity’.

Principally, all interviews collected for this research are retrospective accounts, produced by the young people in their late teens or emerging adulthood, who had a migratory experience as children. Thus, their present stories are grounded in memories of childhood, upbringing, friendships, the departure of one or both parents to Sweden, their own migration as a child and growing up in a new country. According to Fox and Alldred (2019: 27), these retrospective accounts can be defined as personal memories, which are ‘materially affective’, as they both mediate young people’s past experiences but also produce an embodied material affect on their current lives. In a similar vein, Keightley (2010: 5) defines memory ‘as a lived process of making sense of time and the experience of it’.

In line with these definitions, this article sheds light on how memory and rememberances of the past have the capacity to transform the present experiences of young Poles and Romanians in Sweden. Thus, constructing their personal accounts through visual images helps to elicit how memories work. As highlighted by den Besten (2010), when talking about drawings or photographs related to places that matter in these young migrants’ current lives, they tend to reveal strong emotional attachments shared between them and the locations back in their homelands. Leyshon (2015: 626) takes this point further by underlining that ‘memory is mobilized into a practice of self through both the creation of memories and the recall of affect’. In other words, memories about places in the past are closely intertwined with the production of personal identities and emotional bonding in the present.

In what follows we outline how the theoretical concepts discussed above underpin the methodological choices and empirical results set out below.

Research participants and methodology

Engaging children and young people in post-accession European mobile families in research in Sweden is a novel and still emerging research practice, in which we are making the first exploratory steps (e.g. Shmulyar Gréen et al. 2021). In our research project, we met a total of 18 participants from Poland (n=12) and Romania (n=6). We interviewed most of them on two occasions – and some on either one or three occasions – between May 2019 and April 2021.

The recruitment of interviewees2 took place through multiple channels, including mother-tongue language courses, Facebook posts, visits to Polish and Romanian churches, contacting gate-keepers within the Polish and the Romanian communities in Gothenburg and some snowballing. The criteria for selection were young Poles and Romanians who had arrived in Sweden before turning 18 to join one or both parents and who had been living in the country for at least two years. For the recruitment of the interviewees, we used information letters and the project’s advertising cards in three languages – Polish, Romanian and Swedish – to encourage potential participants to pick the language with which they felt the most comfortable, while consenting to take part.

In our sample, 16 participants arrived in Sweden as children under the age of 18 and two were just turning 18. A common pattern was that young people, together with their mothers and, in several cases, their younger siblings, joined their fathers, who came to work in the country after Poland’s and Romania’s accession to the EU. At the time of the interview, their ages ranged between 16 and 29 years old (the majority of them under 25); most of them lived in the Gothenburg region, some were enrolled in high school, while others were studying at university or working. Contrary to our initial intention to engage more-recent arrivals in our study, the interviews turned out to be more retrospective in character, whereby some young people had arrived in Sweden four years ago and others had lived there for 12 years. The participants’ stories thus contained both retrospective accounts of their childhood and migration experiences and current important events in their lives, which we analysed using their own interpretations linked to the broader context of their mobile lives (den Besten 2010; White, Bushin, Carpena-Méndez and Ní Laoire 2010). All the interviews were conducted in Swedish and transcribed verbatim. The choice of the language was a matter of negotiation, as most of the respondents said that they preferred to speak Swedish while being interviewed. If any language difficulties emerged during the interviews, we asked the participants to either express themselves in their native language or in any other language that they and the researchers shared – for instance in English.

The research methods were attuned to the idea of agentic children/youth, regarding them as ‘competent and accomplished research participants’ (White et al. 2010: 144) even if their language competence varied. In order to prioritise the issues that young migrants themselves deem important to talk about, we used a combination of qualitative interviews and visual materials, such as life-lines, network maps (Pirskanen, Jokinen, Kallinen, Harju-Veijola and Rautakorpi 2015) and drawings or photographs (Luttrell 2010; White et al. 2010) produced by the participants themselves. It is important to underline that the visual images were both a starting point in the construction of the young people’s personal narratives as well as meaningful facilitators of further communications between the participants and the researchers. In line with Luttrell (2010: 224), a visual methodology provides researchers with a ‘need-to-know-more stance’ allowing them to interpret the linkages between young people’s images, voices and narratives in specific contexts. In such a way, the value of this methodology is that it invites young people to ‘make deliberate choices to present themselves and others’ (2010: 224) through the relationships and networks which play(ed) an essential role in their own lives. At the same time, self-produced photographs and drawings can ease awkwardness when talking about sensitive issues in the face-to-face setting of an interview, allowing the young people to reflect freely on the content and the subjective meaning of the images they choose to share.

In this article, we focus mainly on the analysis of the drawings and photographs related to meaningful places and on the narratives produced in relation to these during the interviews with 11 female and seven male young people. The empirical material is composed of 37 interviews and 21 photographs and drawings that the participants chose to share with us during our meetings. The drawings and photographs were produced by the participants in the time between the first and the second interview in order to identify places and spaces which were less available to us as researchers; this means that the process of production of most of the images is outside the scope of this article (e.g. White et al. 2010). Importantly, we did not instruct young people to produce any particular kind of image but, instead, asked them to document ‘whatever matters most’ (McGovern and Devine 2016) in physical places and virtual communities in Sweden, in their home countries or elsewhere in the world. To maintain our focus on significant relationships and everyday encounters, we suggested that young people thought of places where they felt included, socially recognised and at ease – or, on the contrary, places which they tried to avoid or from which they were excluded. Initially we assumed that the younger the participants were the more often they would choose to draw before taking photographs. It turned out instead that, independent of their age, the participants drew on fewer occasions, often referring to the fact that their drawing skills were ‘primitive’ (White et al. 2010: 152). Not all young people remembered to bring the drawings or photographs with them and some images shared with the researchers could not be used as illustrations in publications for ethical reasons, as they contained pictures of family members, friends or distant relatives. However, ‘talk on places that matter’ was present in all interviews, with or without the illustrative support of visual images.

While analysing the visual images produced by the young migrants, we followed Desille and Nikielska-Sekula (2021: 7) in their understanding that ‘context is crucial if we are to convey any trustworthy research findings through images’. Thus, in our analysis, the visual images were not treated as independent empirical data per se but, rather, as within a context of young peoples’ narratives about mobility and socio-spatial practices of re-building significant relationships post-migration (e.g. White et al. 2010). Grounding our interpretations of the visual images, we analysed all the interviews using NVivo software to organise and classify the data. The specific thematic codes were refined into sub-categories, including the themes of places and of inclusion and affectionate closeness versus exclusion and misrecognition, which were analysed in more detail through memo writing and systematic comparison.

When it comes to the analysis of images of and talk about places, we developed an analytical strategy following Leyshon’s (2015: 634) idea that place provides a position from which ‘the self can speak to itself and to others’. In this way, images of and talk about places served several purposes, including becoming a point of departure for accounts of memories, facilitating communication and trust between us as researchers and the participants and invoking emotional and sensorial experiences that helped young migrants to reflect about events and experiences they had rarely been asked about before (see e.g. Desille and Nikielska-Sekula 2021; White et al. 2010). Avoiding an over-interpretation of the images’ quality or becoming ‘visual translators who tell the viewer “what they should see”’ (Moskal 2010: 26), we sorted the drawings and photographs according to analytical categories suggested by Gustafsson (2002: 22–23), including what, in their content, could indicate the geographical location of the place, the material forms expressed in the exhibits and, finally – supported by the narrative accounts – what meanings the young people ascribed to the spaces they considered important.

While acknowledging the richness that the visual images brought to our understanding of young peoples’ place-making, we are aware of the potential weaknesses and the sensitivity inherent in these methods. To name but a few, visual images produced and talked about by the participants provided an ‘excess of information and impressions’ (Frers 2021: 88), far too rich compared to what we were able to capture in the analysis. The multi-sensory nature of the visual material, including the voices, the smells, the affection or the sadness are hard to account for through static images. Moreover, while drawings were mainly recently produced for the project, the photographs were more often dug out from drawers or from the young people’s photo libraries in the mobile phones and the people depicted in the images could not be asked for consent for taking part in the research. Thus, guided by the ethical rules aimed at anonymising and reducing the risk of cross-identification, we had to minimise the personal character of these images and, in some respects, defy young migrants’ agency to decide their own terms of self-representation.

Findings

The overall results of the analysis highlight that, while being mobile, young people actively preserve their connections to the distinct places of their childhoods and, at the same time, demonstrate strong attachments to new places in specific localities and spaces post-migration. Among the 21 images that the young people chose to share with us, all but two had a clear geographical location. Roughly half of all the images showed places located somewhere in Sweden while the other half showed places and spaces in the home countries of Poland or Romania. In their content, the photographs and drawings contained portraits of the participants’ nuclear and extended families, friends’, families’ and grandparents’ houses, personal dwellings and classrooms, church gatherings, streets, animals and images of nature. Among the places and spaces that the young migrants chose to talk about, instead of providing visual data, they talked about parental homes, schools and school yards, shopping centres, large cities in both the home and foreign countries, as well as workplaces, neighbourhoods and digital spaces. While most of the place images were quite unique and some were quite personal, all of them portrayed the ‘triviality of the everyday’ (Desille and Nikielska-Sekula 2021: 16), such as ‘hay balls in a field’, ‘a garden in the countryside’ or ‘a street in the home town’.

When analysing young Poles’ and Romanians’ own narratives related to each of the place images or about the places that mattered to them, four salient meanings of places emerged. Firstly, a larger group of place images initiated memories, symbolising feelings of mutual care, familial love and learning attached to their birth countries and their relationships to close and extended family members in both the past and the present. Secondly, another important meaning conveyed by the images related to places where young people felt at ease, safe and familiar within the new environments post-migration. Thirdly, several images illustrated the participants’ rooms and flats, conveying an important meaning of emerging adulthood, which young migrants had to ‘work’ hard for in order to accomplish their personal development and to feel independent and self-confident. The fourth important meaning emanating from the place images, invoked feelings of being excluded and misrecognised as well as the coping strategies used in places both in Sweden and in the country of birth.

Mutual care, familial love and learning

As mentioned above, the half of the visual images centred around people, houses, fields etc. back in the countries where the young participants were born. The most lively discussions during the interviews were about the drawings and photographs showing the places where participants’ grandparents and other kin currently live, back in Poland and in Romania. The meanings attached to these places were described in terms of mutual care, familial love and learning. Antoni came to Sweden from Poland when he was almost 18 years old. When he was a teenager, his parents and his younger sibling moved to Sweden, while Antoni decided to remain with his grandparents. Now aged 25 and living in Sweden himself, he visits Poland quite often and especially the village where he grew up.

This picture was taken two weeks ago, when I visited Poland. Here you can see some hay balls in a field and a tractor. (…) With this photo I want to show you a place which reminds me of the time when I was a child. It was the most fantastic and carefree period in my life. The picture is taken just outside the house where I grew up before my parents moved to Sweden. When they did, I had to move in with my grandparents in another village. (…) The tractor you see belongs to my uncle, who runs a farm. It is the same tractor that I used to drive together with him. (…) He let me steer the wheel and it was just a dream for me as a child. (…) He taught me how to drive a tractor when I was quite young and when I got older, I could ride across the fields on my own. (…) It felt great and exciting, I did something that was fun, that I liked a lot. (…) I could, at the same time, help my cousin, my uncle’s son; he was younger than me and I felt as if I was his older brother and could teach him things. (…) I mean to say that this indeed was a good time in my life even if it was ‘an orphan period’. In this place, it was easier for me to accept that my parents had moved [to Sweden] because my uncle and his wife became my extra parents.

Figure 1. Photograph of hay balls in a field

To an outsider, the photograph which Antoni shared (Figure 1) might appear uneventful and impersonal. However, in line with findings by den Besten (2010: 191), for Antoni, who is a young adult, this image of the field with hay balls is ‘treasured for its ability to symbolically recreate the homeland left behind’. The place he talks about with such devotion is still important to him because it reminds him of ‘a carefree childhood’ and also of people who took care of him and made him feel safe and loved. Another important connotation of this image is that his ‘extra parents’ taught him important skills in life. A sense of responsibility and active care for others, as well as practical knowledge about how to drive, were, following (Fox and Alldred 2019), materialised and deepened later in Antoni’s life due to the positive memory he had of being trusted and believed in as a young child.

Vera (aged 18), another participant from Poland, went to Sweden at the age of 6, together with her mother and younger siblings, to join their father, who had been working in Sweden for some years. She drew several sketches of places she wanted to share with us, one of them her grandparents’ house (Figure 2).

It is the grandparents on my mother’s side that I mainly keep in touch with. It is also with them that my boyfriend has developed some kind of relationship. They like him. I do not have to worry about them starting arguing or something. (…) I feel I got a bit of my granny’s character. (…) When she sets her mind to something, she does it herself in her own way. (…) She has such drive. She is getting older now, but she gets things done, she is just that kind of person. I remember one summer [when I was younger] and my mother had to take her driving licence, me and my brother stayed with our granny during the day, when my mum was away. (…) My granny is just such a person. She supported my mother quite a few times. [When I visit her now], I feel I can really talk to her and I realise that I really need it.

Images of country houses and fields often feature in the visual data of this project because, for Antoni, Vera and practically all the other participants, mobility to Sweden implied a transition – from living in small towns and villages and being socialised within their extended families, to the suburbs of the larger Swedish cities where they had to manage their lives without a supporting kin network. The young people’s own mobility to

Figure 2. Drawing of the grandparents’ house

Sweden also implied that their daily contact with their grandparents and other kin back ‘home’ has now transformed into a distant co-presence through visits and virtual communication on the phone. This is why Vera and Antoni, like several other young people in our study, said how much they missed and longed for specific belovèd family members back home. Thus, the images they created carried what Marcu (2012) describes as an ‘emotional echo’, providing a connection to spaces where young migrants felt safe, cared for and loved, being surrounded by people whom they knew and trusted. While these illustrations can be perceived as signs of the absence in their lives of those places and being missed by someone there, they also bear witness to the building of active relationships that young migrants engaged in through frequent visits back to the countries of birth, daily calls to the grandparents and preserving memories of emotional and physical closeness as ‘a sense of connection that exists in reality (…) but also in an imaginary realm’ (Moskal 2015: 148).

Feeling at ease, safe and familiar with new environments

Another theme, notable in the images, relates to places and spaces beyond the circle of family, yet where the participants feel at ease, safe and in a familiar environment. Among the photographs expressing these meanings, quite a few depict new places in Sweden where the young migrants spent time with friends, romantic partners or on their own. For instance, several Poland-born participants shared images related to their activities with their co-ethnic peer group within the Polish Catholic community in Sweden (see Shmulyar Gréen et al. 2021). Other images related to Sweden show, for instance, a public library, a schoolyard or port cranes near the sea. Taya’s story epitomises the ways in which young migrants appropriate new places and build emotional attachments to them post-migration. Now aged 20, she was born in Romania and came to Sweden at the age of 16 to join her father – a common pattern among the young people participating in this study. Taya was eager to share several images related to both her home village in Romania and her current dwelling in Gothenburg. One photograph, picturing a typical red Swedish cottage by the sea (Figure 3), stood out from the rest of her images.

My boyfriend’s grandparents live in this house during the summertime. When he introduced me to them for the first time it was in this house on an island outside Gothenburg. At first, I felt why should I meet his grandparents for the first time in their summer house? It did not feel comfortable. When we finally met, I realised that the atmosphere there was very much like in the countryside in Romania because everyone knows each other, the island is tiny, and everyone is somehow a relative to one another. It felt so relaxing to be there (…). That is why, now and then when I am stressed, or overwhelmed with schoolwork or just want to take it easy, we just go to this house on the island for a weekend.

Figure 3. Photograph of a red Swedish cottage

Taya explains that it took some effort to get accustomed to new people on the summer island. In line with Moskal (2015: 149), the atmosphere of a close community where ‘everyone knows each other’ helped her to ‘turn (…) the unknown into known’, to find a resemblance with her village back in Romania and to feel at ease. As Bennett (2011: 4) underlines, ‘knowing people around us gives us a feeling of security’. Taya’s and other migrant youth’s stories clearly illustrate the importance of familiarising oneself with new places and ‘being recognised as part of the community’ (Sime et al. 2020: 92) in order to feel more comfortable and safe. At the same time, these stories speak of the transnational connectivity produced through memories of places of birth and up-bringing with ‘the lived experience of locality’ (Moskal 2015: 149) in their new home country.

‘Peace and quiet’, relaxation and self-reflection

In addition to places, seen as important by the young migrants due to their interactions with other people, we want to focus on the places which the participants appreciated for providing them with a possibility for some ‘peace and quiet’, for relaxation and self-reflection. At the time of the interviews, 13 out of the 18 participants were young adults, studying at university or working. Several of them had just moved out from the parental home or were planning to do so. Privacy and autonomy, which their own apartment or a room in a family house could allow, were especially valued by the young people. In multi-child families, a private space was hard to find when they moved to Sweden, as several participants used to share rooms with one or more younger siblings. Antoni, 25 (18 on arrival) whom we mentioned above, described his newly acquired one-room apartment with pride and gratitude:

This is a photo of my apartment (…). The reason why I show it is because [this place] is a kind of oasis for me. (…) I like this place and I like to come back to it [after work] because it is a quiet place, where I can just relax. (…) It is a safe place (…) and I am so grateful that I could move and start an independent life here (…).

The emphasis on safety and relaxation, as well as privacy and independence, that Antoni accentuates also echoes in other research on young migrants’ home-making practices (e.g. McDonnell 2020). Another relevant aspect of having their ‘own place’ is raised by 23-year-old Monica, who was also born in Poland but moved to Sweden aged 11, when she reflects on her own apartment as a space for a new stage in her life:

My new apartment [has a meaning of its own]. Not related to Poland, I would say, not in terms of being a childhood memory, but rather it [stands for] my adult self. I went through tough times [when I arrived in Sweden], but I made it. [The feeling I associate with the apartment] is a sense of confidence in myself.

What Antoni, Monica and other young people tell us is that getting their own place to live coincides with them entering a stage of ‘emerging adulthood’ (Arnett 2000: 469). During this stage they go through different ‘independent explorations of life’s possibilities (…) when they can gradually arrive at more enduring choices in love, work, and worldviews’ (2000: 479). For the participants in our study, one such an exploration is leaving the parental home and also becoming independent and self-reliant individuals. While these transitions are common to other non-migrant youth growing up in Sweden, for the respondents in our study, they are experienced against the backdrop of parallel processes related to the multiple ruptures and a sense ‘in-between-ness’ both in Sweden and in their birth countries (e.g. Tyrell et al. 2019).

Figure 4. Photograph of a bedroom

Another issue on which it is important to reflect is that their own apartment, their own room within the parental home and places in nature are all singled out as spaces for self-reflection and sometimes nostalgia about their childhood in their countries of birth. The fact that young migrants tend to situate their ‘home’ in dual or several locations depending on their attachment to places has been observed by a number of researchers (inter alia Fresnoza-Flot and Nagasaka 2015; Haikkola 2011; Moskal 2010, 2015). The story of Taya (20; arrived aged 16), whom we introduced earlier, clearly illustrates one more important aspect, namely ‘the extent of the emotional, relational and cultural work involved in (…) re/making home’ (McDonnell 2020: 6):

This is a picture of my bedroom [in the house in Romania]. Usually lots of plush toys everywhere. I must have them around me, I use them instead of pillows. (…) It may look quite childish, but it feels like me. [My parents] wanted to refurnish the room last summer, but I said ‘No way’. I said, ‘The only thing you can change is the door’, that you see in the mirror. Nothing else. (…) In fact, there are not that many plush toys left because I took them all to Sweden. [Taya shows another picture that appears to be almost the same] Here you see my room in Sweden, it is quite similar. We could not find the same type of sofa as I have in Romania, but it will do. It looks almost the same, just the bookshelf is larger. (…) I have all my papers there that I saved since kindergarten, year after year. I try to move all my papers from Romania to Sweden, bit by bit. My mom says: ‘You cannot take them all with you’. And I answer: ‘Yes, I can. (…) I have saved them all in boxes’. It feels fun to go through the papers and realise… [how I have developed].

Taya’s description of the material possessions she took from Romania to Sweden suggests the importance of her favourite toys, furniture, school notes and books (Figure 4) for the ‘humanising and personalising effect’ (McDonnell 2020: 11) of her own current space. At the same time, holding tight to the material objects from her childhood in Romania in her room in Sweden, Taya tries ‘to conserve memories of the past’ (Fox and Alldred 2019: 22) that enable her to maintain a spatial and relational connection to her favourite place back in Romania, the house where her grandmother currently lives. In other words, while re-making her home as a young adult, Taya – and other participants – bridge ‘the gap between past and present, and between here and there’ (Moskal 2015: 149) and create a space where they can realise how much they have developed over the years.

Places of exclusion and misrecognition

Along with the places for social inclusion and appreciation, we asked the participants about the places where they might have felt excluded from or misrecognised. Only on a few occasions did the young people have images to share with us while talking about the instances of exclusion or a sense of ‘non-belonging’ post-migration. Among them were images of a shopping centre, symbolising ‘a risky and unpleasant place’ (Antoni, 25) or a mega city such as New York, standing for ‘a modern and yet indifferent place’ (Matilda, 21; 9 years old on arrival). While the meanings of these places emanate more from imagination than experience, these images were presented as a contrast to the places where the young people felt at ease.

There were other places where the young migrants did not feel that they were welcomed or where they had direct ‘exclusionary experiences’ (Fangen and Lynnebakke 2014: 49). Wanda, aged 19 (7 on arrival) and Faustyna, aged 23 (15 on arrival), both from Poland, described a growing sense of depreciation and not belonging while visiting their grandparents or taking part in family celebrations back in Poland. They both point out how they are ‘losing a previously close relationships’ and ‘feeling unwelcomed’ due to their ‘new’ way of life, faith or appearance acquired while living in Sweden. Other young people, such as Antonina, 29 (16 years old on arrival), also from Poland, talked about their experiences of being ‘ignored, bullied or discriminated against’ at their workplace in Sweden because of their migrant and religious background. Antonina landed a temporary position within a service sector, a ‘dream job’ in her own words, working on different tasks which did not require a university degree. She wanted ‘to learn things through work’ and was a diligent employee. After three years she decided to apply for a permanent position with the same employer; however, she received a negative answer, without really understanding the reason:

[The way the employer handled the situation] I felt I was being bullied and discriminated against. (…) I was anxious even being around that place. (…). For them, it was me who was a problem. [I dare say that it was] because of my [ethnic] background and my faith.

Antonina often used the lenient expression ‘I dare say’, indicating that she was aware that she talked about the experiences of being ‘out of place’, ‘othered’ and indeed discriminated against in a country known for its values of equality and tolerance of people with different ethnic backgrounds. Nonetheless, the way in which she and some of the other participants coped with similar situations echoes research by Fangen and Lynnebakke (2014), Sime et al. (2020), Zontini and Peró (2020) and others who underline the growing ‘structural barriers (…) that limit the possibility of proactive responses’ (Fangen and Lynnebakke 2014: 55) on behalf of the young migrants in several European countries.

The most prominent examples of exclusion and insecurity were expressed in relation to the structural barriers experienced by the participants in places such as neighbourhoods and schools. Jonatan travelled to Sweden from Romania when he was 12 years old, together with his father, while his older sister stayed in Romania to finish her high-school education. Jonatan and his father joined Jonatan’s mother, who had found a job prior to their relocation to Sweden, where they settled together in an apartment in one of Gothenburg’s economically marginalised suburbs. In Jonatan’s own words, the first thing he saw on the street in his neighbourhood was ‘a guy running after another guy with a gun in his hands’. By recounting how he had to navigate the conflict and violence he repeatedly witnessed as a child in Sweden, Jonatan (now 24) admitted that, in order to protect himself, he had to learn the ‘rules of the game’:

I joined a gang, which was the best [shield]. No one could do anything to them. (…) I did it just to keep safe. So that they did not bother me (…) because I did not speak much Swedish at that time. (…) I was with them, or kind of. (…) I simply took their side to avoid being disturbed myself. (…) You have to be smart and play by the rules.

Even if Jonatan’s encounters with violence may appear to be extreme and out of the ordinary for most young migrants in Sweden, it speaks of a sense of marginality and insecurity in the place where he lives that pushed him to develop ‘mastery experiences’ (Fangen and Lynnebakke 2014) to avoid risky situations and ‘stay safe’. At the time of the interview, he disclosed that the experiences of vulnerability in his childhood made a clear imprint on how and where Jonatan saw his future, by striving to move from the neighbourhood where he grew up to safer areas outside the city of Gothenburg.

Other places, more often mentioned, where the participants said that they were struggling with social exclusion and bullying, were schools and public playgrounds in the school areas. An overwhelming impression surfacing from the interviews was the feeling of estrangement and loneliness felt by our young migrants, especially in the first years following their arrival in Sweden, when they had not yet mastered a new language and had difficulties in making new friends. Anna,16, moved from Poland to Sweden more recently (aged 12) and appears to be very active in making friends and socialising. Despite her enthusiasm and openness to all new contacts in Sweden as well as her agentic attitude in asking adults for help, she admits:

I had lots of friends in Poland, I was a popular girl among peers in my class. (…) When I celebrated my birthdays, I used to have big parties with a lot of people at home. And here [in Sweden] it was just the opposite. For almost two years people treated me as an ‘air’, as if I did not exist. (…) I talked to the teachers several times and pointed out that no one talks to me at school and I felt lonely. I had to sit alone in the school canteen and eat lunch by myself, I had to do basically all things in school by myself. No one spoke a word to me. The teachers took up this issue once before the whole class, but nothing changed. They did not want to be friends with me.

Like the young migrants in Fangen and Lynnebakke’s study (2014), Anna and some other participants did not give up when they faced obstacles to being acknowledged by their peers in school. When remembering these experiences during the interviews, Anna had ambivalent feelings about school as a meaningful place. She had to change schools and also classes to be able to cope with a sense of being excluded. While developing various tactics of resilience, she asked her teachers for help, talked with her fellow pupils despite her fear of being rejected and kept her mother appraised of the situation while, at the same time, trying to spare both of her parents from the painful details. In these struggles, Anna admitted that she was living in emotional distress and loneliness, spending a lot of time on social media. It was an alternative space where several other participants found peers – who shared the same mother tongue and had other interests in common – to befriend.

Conclusion

This article set out to examine how the 1.5 generation of Poles and Romanians who moved to Sweden following their family’s mobility lead, (re)shape the connections and ascribe meanings to places post-migration. More specifically and from the perspective of significant relationships in the course of youth mobility, the article contributes to filling the gap in research on CEE-born young people living in Sweden with a focus on how they foster their ties to specific places and spaces (locally and transnationally) post-migration.

Emphasis is put on the analysis of the multiple meaning-making of places (Gustafsson 2002), following which four salient themes emerged. Drawing on the concepts of translocality and place (Assmuth et al. 2018; Massey 1994; Moskal 2015), the article highlights that places – as articulations of social relationships based on mutual care, familial love and learning – stretch beyond a particular geographical location in time. The meanings of these places are produced and reproduced in dialogue between the memories of childhood and upbringing before migration and young people’s current perceptions of their lives in Sweden. Our results indicate that, through this dialogue, young Poles and Romanians actively compare their positive memories of places where they grew up with the new translocal places which they appropriate through everyday social practices in Sweden (e.g. Moskal 2015). Following Fox and Alldred (2019) and Keightley (2010), we argue that memories can be mobilised and materialised into a practice of self through remembering places and people who inhabited them in the past and by the active construction of role models for whom young people have become and who they want to become in the future.

As noted by Luttrell (2010: 225), ‘the mode of visual research (…) is dynamic and relational’. Indeed, the article has shown that the in-depth interviews, generated through the visual images produced by the participants – such as drawings and photographs – are particularly valuable to ‘ground the research in places and focus on the embodied experiences’ (Desille and Nikielska-Sekula 2021: 3) of the young migrants. Apart from enabling young people to decide for themselves which issues they want to talk about, the added value of this methodology is the way in which it facilitates communication and builds trust between the participants and the researchers. It also promotes self-reflexivity and multiple identity constructions by the young people, beyond being a migrant (e.g. White et al. 2010). Based on this rich methodological approach, our analysis reveals that, due to the families and their own mobility, young people tend to develop multiple identities and attachments to people and places in both the country of origin and the country of their current settlement (e.g. Fresnoza-Flot and Nagasaka 2015). Moreover, visual images provide an important insight into how young migrants continuously negotiate the complexity of place-making and how they use memory and feelings to preserve, develop and reconstruct their social relationships post-migration, both in Sweden and back in their countries of birth.

Visual methodology has thus been a creative tool to facilitate the reconstruction of memories related to important places and people. In line with Leyshon (2015), by remembering and re-telling stories about important places, young migrants feel connected to those who care/d about them and become reassured about where they currently belong. Regarding the second salient theme of place-making, the research discussed in the article suggests that feeling at ease, safe and familiar with new environments is enabled by positive memories of belonging, ‘knowing people’ (Bennett 2011) and a sense of still being a part of similar local communities in the young migrants’ countries of birth.

Drawing or illustrating these places through photographs, young people demonstrate the strength of connections to the home country, the importance of visits, the regularity of communication and the ‘hard work’ and efforts that lie behind the creation of their new homes, as ‘emerging adults’ (Arnett 2000). Fond memories of their own rooms and the houses of their parents and kin in places from their childhood serve as a strong emotional attachment to their countries of birth (Marcu 2012) but also as a material reminder of their past, which now serves as a stepping-stone for their present and future identity-building (e.g Fox and Alldred 2019). These new and independent spaces are appreciated for generating the feelings of ‘peace and quiet’, relaxation and self-reflection, as a means for young people to come to terms with who they have become over the years. In places of their own or in nature, serving as a refuge for the challenges they may go through, young migrants engage in activities of remembering what they were appreciated for and thus transforming the places in Sweden into their new homes.

Finally, the findings also demonstrate that processes of inclusion and exclusion can occur together in the same places (Farrugia 2015). Being seldom represented by visual images, the places of exclusion and misrecognition have been identified translocally, related to the young people’s ‘everyday spaces’ such as schools, home, neighbourhoods and work. Recalling the examples of being bullied in school, being exposed to violence in the neighbourhood, discriminated against at work or not being loved and appreciated by both close and extended family members in either Sweden or the country of birth, young migrants reveal the personal challenges and structural barriers preventing them from becoming fully socially included (e.g. Fangen and Lynnebakke 2014). While the experience of being marked as ‘different’ had a negative impact on their self-confidence as young adults, the participants manifest an agentic position in avoiding these places, developing coping strategies or keeping an active distance from places and relationships in which they are not appreciated for who they are.

Notes

- The project ‘Transnational Childhoods: Building of Significant Relationships among Polish and Romanian Migrant Children after Reunification with Parents in Sweden’ [2018-00369] is funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE, 2019–2021). The project leader is Professor Ingrid Höjer.

- The project was granted ethical approval by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority [Reg. No. 2019–02504]. Following the ethical guidelines, we ensured the participants’ anonymity and integrity by asking them to choose a fictitious name and by carefully concealing other personal data to avoid easy identification.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID IDs

Oksana Shmulyar Gréen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1931-9789

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1931-9789

Charlotte Melander  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8228-8647

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8228-8647

Ingrid Höjer  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4584-1917

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4584-1917

References

Arnett J.J. (2000). Emerging Adulthood. American Psychologist 55(5): 469–480.

Assmuth L., Hakkarainen M., Lulle A., Siim P.M. (2018). Translocal Childhoods and Family Mobility in East and North Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bennett J. (2011). Looks Funny When You Take its Photo: Family and Place in Stories of Local Belonging. Manchester: University of Manchester, Sociology Working Paper No. 1.

Delmi (2020). Migration to Sweden in Figures. https://www.delmi.se/migration-i-siffror#!/kartaover/utrikes/fodda/perso... (accessed 23 May 2022).

Den Besten O. (2010). Local Belonging and ‘Geographies of Emotions’: Immigrant Children’s Experience of their Neighbourhoods in Paris and Berlin. Childhood 17(2): 181–195.

Desille A., Nikielska-Sekula K. (2021). Introduction, in: K. Nikielska-Sekula, A. Desille (eds), Visual Methodology in Migration Studies, pp. 1–27. Cham: Springer.

Fangen K., Lynnebakke B. (2014). Navigating Ethnic Stigmatisation in the Educational Setting: Coping Strategies of Young Immigrants and Descendants of Immigrants in Norway. Social Inclusion 2(1): 47–59.

Farrugia D. (2015). Space and Place in Studies of Childhood and Youth, in: J. Wyn, H. Cahill (eds), Handbook of Children and Youth Studies, pp. 609–624. Singapore: Springer.

Fox N., Alldred P. (2019). The Materiality of Memory: Affects, Remembering and Food Decisions. Cultural Sociology 13(1): 20–36.

Frers L. (2021). Conclusions: Touching and Being Touched – Experience and Ethical Relations, in: K. Nikielska-Sekula, A. Desille (eds), Visual Methodology in Migration Studies, pp. 85–95. Cham: Springer.

Fresnoza-Flot, A., Nagasaka I. (2015). Conceptualising Childhoods in Transnational Families: The ‘Mobile Childhoods’ Lens, in: I. Nagasaka, A. Fresnoza-Flot (eds), Mobile Childhoods in Filipino Transnational Families. Migrant Children with Similar Roots in Different Routes, pp. 23–41. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gustafsson P. (2002). Place, Place Attachment and Mobility – Three Sociological Studies. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, Department of Sociology, PhD thesis.

Habib S.,Ward M. (2020). Youth, Place and Theories of Belonging. New York: Routledge.

Haikkola L. (2011). Making Connections: Second Generation Children and the Transnational Field of Relations. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37(8): 1201–1217.

Harris A., Baldassar L., Robertson S. (2020). Settling Down in Time and Place? Changing Intimacies in Mobile Young People’s Migration and Life Courses. Population, Space and Place 26(8): e2357.

Jørgensen C.R. (2016). ‘The Problem Is That I Don’t Know’: Agency and Life Projects of Transnational Migrant Children and Young People in England and Spain. Childhood 24(1): 21–35.

Keightley E. (2010). Remembering Research: Memory and Methodology in the Social Sciences. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 13(1): 55–70.

Leyshon M. (2015). Storing Our Lives of Now: The Pluritemporal Memories of Rural Youth Identity and Place, in: J. Wyn, H. Cahill (eds), Handbook of Children and Youth Studies, pp. 625–636. Singapore: Springer.

Luttrell W. (2010). ‘A Camera is a Big Responsibility’: A Lens for Analysing Children’s Visual Voices. Visual Studies 25(3): 224–237.o10.1177/0907568220961138

Marcu S. (2012). Emotions on the Move: Belonging, Sense of Place and Feelings Identities Among Young Romanian Immigrants in Spain. Journal of Youth Studies 15(2): 207–223.

Massey D. (1994). Space, Place and Gender. Cambridge: Polity Press.

McDonnell S. (2020). Narrating Homes in Process: Everyday Politics of Migrant Childhoods. Childhood 28(1): 118–136.

McGovern F., Devine D. (2016). The Care Worlds of Migrant Children. Childhood 23(1): 37–52.:

Melander C., Shmulyar Gréen O. (2018). Trajectories of Situated Transnational Parenting: Caregiving Arrangements of East European Labour Migrants in Sweden, in: V. Ducu, M. Nedelcu, Á. Telegdi Csetri (eds), Childhood and Parenting in Transnational Settings, pp. 137–154. Cham: Springer.

Melander C., Shmulyar Gréen O., Höjer I. (2020). The Role of Trust and Reciprocity in Transnational Care Towards Children, in: J. Hiitola, K. Turtiainen, M. Tiilikainen, S. Gruber (eds), Family Life in Transition Borders, Transnational Mobility, and Welfare Society in Nordic Countries, pp. 95–106. London and New York: Routledge.

Moskal M. (2010). Visual Methods in Researching Migrant Children’s Experiences of Belonging. Migration Letters 7(1): 17–31.

Moskal M. (2015). ‘When I Think Home I Think Family Here and There’: Translocal and Social Ideas of Home in Narratives of Migrant Children and Young People. Geoforum 58: 143–152.

Pirskanen H., Jokinen K., Kallinen K., Harju-Veijola M., Rautakorpi S. (2015). Researching Children’s Multiple Family Relations: Social Network Maps and Life-Lines as Methods. Qualitative Sociology Review 11(1): 50–69.

Shmulyar Gréen O., Melander C. (2018). Family Obligations Across European Borders: Negotiating Migration Decisions Within the Families of Post-Accession Migrants in Sweden. Palgrave Communications 4: 28.

Shmulyar Gréen O., Melander C., Höjer I. (2021). Identity Formation and Developing Meaningful Social Relationships: The Role of the Polish Catholic Community for Polish Young People Migrating to Sweden. Frontiers in Sociology 6: 660638.

Sime D., Moskal M., Tyrrell N. (2020). Going Back, Staying Put, Moving On: Brexit and the Future Imaginaries of Central and Eastern European Young People in Britain. Central and Eastern European Migration Review 9(1): 85–100.

SCB (2019). Barn och unga födda i 11 nya EUs medlemsländer. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden, Unpublished data from the national register on children and families in Sweden.

SCB (2020). Uppväxt villkor för barn med utländsk bakgrund. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden.

Tyrrell N., Sime D., Kelly C., McMellon C. (2019). Belonging in Brexit Britain: 1.5-Generation Central and Eastern European Young People’s Experiences. Population, Space and Place 25(1): e2205.

Waerdahl R. (2016). The Invisible Immigrant Child in the Norwegian Classroom: Losing Sight of the Polish Children’s Immigrant Status through Unarticulated Differences and Behind Good Intensions. Central and Eastern European Migration Review 5(1): 93–108.

White A., Bushin N., Carpena-Mendez F., Ní Laoire C. (2010). Using Visual Methodologies to Explore Contemporary Irish Childhoods. Qualitative Research 10(2): 143–158.

Zontini E., Peró D. (2020). EU Children in Brexit Britain: Re-Negotiating Belonging in Nationalist Times. International Migration 58(1): 90–104.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.