What Do Citizens Do? Immigrants, Acts of Citizenship and State Expectations in New York and Berlin

-

Author(s):Harper, Robin A.Published in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2023, pp. 81-102DOI: 10.54667/ceemr.2023.12Received:

18 February 2022

Accepted:28 June 2023

Views: 7815

Governments make assumptions about immigrants and then craft policies based on those assumptions to yield what they hope will be effective naturalisation outcomes: state security and trustworthy citizens. This study examines the thoughts, experiences and opinions about citizenship and civic engagement, drawing on a dataset of 150 one-hour interviews with permanent residents and naturalised citizens in New York and Berlin in 2004–2010 and again 2016–2020. It includes those who have naturalised or hold immigration statuses necessary for naturalisation (i.e., those who can and will naturalise, those who can but will not naturalise and those rejected for naturalisation or who do not meet eligibility requirements). I explore how immigrants participate as citizens and privileged non-citizens. My findings include the fact that immigrants define civic engagement – what ‘citizen’ participation means and who participates – more broadly and narrowly than anticipated. Immigrant perceptions of naturalisation and what becoming a citizen meant to them, and how naturalisation personally affected modes of participation. Defensive citizenship stimulated naturalisation but was deemed insufficient in contemporary New York and Berlin to protect immigrants and their engagement. State-designed naturalisation processes ignore immigrants’ perspectives and performative modes of citizenship and, thus, ineffectively select the citizens states say they want.

Introduction: thinking about citizenship and civic engagement

Before Covid-19 forced New York City schools to close, our Parent–Teacher Association (PTA) president called for volunteers to run the afterschool programme, book sale, holiday dance and a writing campaign demanding that the city government provide more autonomy for public schools. Hands shot up. Permanent residents from Italy, Canada, Morocco, Japan and Romania agreed to run these programmes with US-citizen parents (both naturalised and native-born) and others with questionable immigration statuses. I knew some intended to remain permanent residents. Why would they invest so much energy when they were not citizens? My PTA meeting experience is neither new nor unique. Regardless of immigration status, there are countless stories of immigrants providing services. Certainly, immigrants provide labour; that is why many come and are paid. Of course, some immigrants come as religious officiants or forced (sexual and other) labourers or unpaid spouses, all of whose labour is often taken for granted. However, what is more curious is the donation of labour to build the community. In April 2021, President George W. Bush appeared on a television talk show to salute recently naturalised health-care workers. The former president asserted that these doctors, nurses and medical technicians ‘put their lives on the line for a country that wasn’t yet theirs’ (Today with Hoda & Jenna 2021).

If the country ‘wasn’t yet theirs’, when would it be? Are they ‘citizens-in-waiting?’ (Motomura 2006)? Why make sacrifices for the country? Stories about immigrant civic engagement and how it varies by race, gender, ethnicity and immigration status is well studied. These examinations appraise degrees of theoretical citizenness (Harper 2007) – i.e., how well immigrants1 adopt local practices and participate in daily communal life – presupposing a universal, unilinear and progressive immigrant integration path (Harper 2007). The foreigner-to-member adjustment follows the mastery of what Fortier (2017: 3) calls citizenisation, i.e., the ‘integration policy’ that requires non-citizens to acquire ‘citizen-like’ skills and values when seeking citizenship or other statuses (e.g., settlement). This imagined trajectory tantalises policymakers and researchers alike as it promises simplicity and legibility to recalcitrant facts about immigrants’ settlement paths over time and space. It renders immigrants perennially in the process of arriving (Boersma and Schinkel 2018). It confirms the normalcy of settler migration, the rightness of the decision to immigrate and an unspoken subtext whereby receiving societies are inherently better than left-behind places. Simultaneously, it offers the image of migrants negotiating parallel lives (Orton 2010) until ‘the’ magic moment when migrant integration is completed, ostensibly concomitant with naturalisation (Harper 2007, 2017; Sayad 1993) and assume full rights and obligations. It suggests that immigrant civic participation marks successful attachment to adopted countries. It suggests that the process is visible, knowable and desirable even if none of those conditions are true (Boersma and Schinkel 2018). This perspective fixedly represents receiving-state expectations. The metrics capture what we can count or how natives imagine their own ‘good citizen’ behaviour. It ignores the fact that immigrants naturalise (or do not) for a spectrum of strategic or tactical reasons (Harper 2007, 2011, 2017; Sredanovic 2022) and non-rational purposes of identity, social norms or attachment, among others (Harper 2007, 2011).

This article examines the connection between immigrants’ understandings of citizenship and their civic engagement. I explore how immigrants perceive that citizenship (whether they have naturalised, can naturalise, were rejected from naturalisation or have no interest in naturalising) affects their civic engagement. Citizenship can be understood here as naturalisation (the bureaucratic process) or what immigrants believe is constitutive with the lived experience of being a citizen. Following Isin (2019), I suggest that these performances of citizenship – exercising, claiming and performing rights and duties and creatively transforming its meanings and functions – is citizen-making, transforming the collective social meaning of ‘citizen’. These acts of citizenship effectively refuse, resist or subvert orientations – ‘…strategies and technologies in which they find themselves implicated and the solidaristic, agonistic and alienating relationships in which they are caught’ (Isin and Nielsen 2008: 38). Citizen-making transpires independently from formal process or status and whether immigrants are naturalised, can naturalise, are ineligible or are rejected from naturalisation. Naturalisation is not necessarily an outcome of citizen-making. Naturalisation is the state’s formal process to render foreigners citizens. Naturalisation may not accord with what immigrants believe renders them citizens. I posit that immigrants construct their own notions of what citizens are and what formal citizenship does; by shaping the spectrum of what can be considered civic engagement, they remake the idea of citizenship. Immigrant subjects ‘constitute themselves as citizens… as those to whom the right to have rights is due’ (Isin and Nielsen 2008: 2). As Hamann and Yurdakul (2018: 110) assert, immigrants ‘…contest and transform dominant notions of the nation-state, state control, national sovereignty, citizenship, and participation’. These definitions afford new opportunities for citizenship in the modern globalised polity (Isin 2019). Listening to immigrants’ thoughts about naturalisation informs us about contesting exclusion and the emergence of new citizen-outsiders in the state in which they are long-term residents (Byrne 2017).

Governments make assumptions about immigrants and then craft policies based on those assumptions, anticipating effective naturalisation outcomes: state security and trustworthy citizens. Insufficient information about immigrant imaginations of citizenship and related civic engagement can have important policy implications. Naturalisations are the last security border protecting the country from unknown (and potentially dangerous) foreigners. Do those who cannot or will not naturalise and those rejected for naturalisation behave like those whom the state naturalises? Is naturalisation necessary for ‘good’ citizenship? Naturalisation policy is known; it is published on government websites and pronounced through official rhetoric. Shifting the gaze to immigrants’ self-narratives of citizenisation offers prisms into integration and connections with citizenship. This study includes those who have naturalised or hold an immigration status necessary for naturalisation (i.e., those who can and will naturalise, those who can but do not want to naturalise, those rejected for naturalisation or those who do not meet eligibility requirements).

I find that immigrants naturalise for different reasons and this informs their civic engagement. Sometimes, they naturalise to protect themselves from the state, yet naturalisation cannot protect them. Immigrants describe civic engagement or ‘acts of citizenship’ that are more expansive and sometimes narrower than ‘collective or individual deeds that rupture social-historical patterns’ (Isin and Nielsen 2008). Many actions are not revolutionary or intended to affect state power or politics. Some fit normal scopes of civic engagement or are paid. Many respondents would not call what they do ‘engagement’, even when it demands change from the state or society. Often, these actions are quiet but have the propensity to yield quality-of-life improvements. I question how state-designed naturalisation processes ignore immigrants’ perspectives and, thus, ineffectively select the citizens whom the state says it wants. Hopefully, this work on immigrant perspectives on citizenship, naturalisation and civic engagement will inform better state policies. States ignoring immigrant understandings of naturalisation and citizenship do so at their peril.

Why does civic engagement matter?

In their seminal work on participation and democratic practice, Verba, Schlozman and Brady (1995: 1) assert, ‘Citizen participation is at the heart of democracy’. Naturalized citizens are legally and socially understood to be part of the democratic citizenry but what roles exist for potential citizens and how should they participate if political citizenship is not yet (or will never be) an option? The practice of active citizenship is a process, not an outcome. People learn, practice and transmit political knowledge and develop social networks through civic organisations (Verba et al. 1995). Participation serves as a base for mobilisation and social movement activity, to promote social mobility and social recognition (both inside and outside their communities), to develop modes for political influence (Brettell and Reed-Danahay 2011) and to engage with political actors mobilising people already involved in community civic life (Rosenstone and Hansen 1993). Civic engagement can have a meaningful effect on immigrant incorporation and political socialisation in different ways for men and women in both the receiving country (Ramakrishnan 2006; Ramakrishnan and Bloemraad 2008) and sending country (Jones-Correa 1998). Civic engagement can even lead to better mental health by promoting connections to others, sharing experiences and being considered members, thus generating a feeling of full citizenship. As Harper et al. (2017: 211) assert, engagement produces three kinds of benefit: ‘…a broad sense of participation and belonging through civic consciousness at a macrolevel, intermediate-level interactions with “familiar strangers” in public spaces, and more intimate microlevel social connections through family, friendship, and institutions’. They go on to posit that engagement yields important identity and solidarity connections which have the propensity to proffer feelings of belonging and well-being. These include the associational, social organisational and structural relationship connections that arise in encountering spaces from doing things and being with others (Cantle 2005; Orton 2010) and ‘social incidental’ relationships (Orton 2010: 30) or superficial interactions with people (i.e., Harper et al.’s 2017 ‘familiar strangers’) with whom you have regular but fleeting conversations. Civic engagement affects the quality of community life, as higher densities of civic associations reflect higher levels of interpersonal trust and the quality and alacrity of government services (Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti 1994). Putnam’s (2000, 2007) later work on social fragmentation and a lack of civic cohesiveness due to a lack of civic engagement are taken up in the tongue-in-cheek title of Ramakrishnan’s (2006) chapter ‘But do they bowl?’, questioning immigrants’ civic engagement and ability to be mobilised in group-based activities. Putnam’s (2000, 2007) assertion that diversity reduces social solidarity and social capital has been harshly taken to task for its attacks on social cohesion and ethnocultural heterogeneity (Portes and Vickstrom 2011). The search for a traditional communitarian mechanical solidarity built on cultural homogeneity and acquaintances is neither reflective of nor appropriate for the forms of organic solidarity built on heterogeneity, role differentiation and a complex division of labour which one finds in modern society (Portes and Vickstrom 2011).

State expectations for civic engagement

Eligibility requirements for naturalisation in both Germany and the US are time-, money-, presence-, knowledge- and behaviour-based. Effectively, states seek applicants who settle down, follow the law, submit to the regime, are financially solvent and are moderate in comportment and political expression (i.e., non-criminal, non-extremist behaviour). The ‘good moral character’ requirement is a retrospective evaluation of bad behaviour without considering good behaviour. Applications provide no place to cite volunteering, caregiving, participating in or leading associations or protesting in normal politics. Even at naturalisation conferral (normally a protracted private meeting with a civil servant in Germany or a public ceremony in the US) applicants are asked whether or not they lied on their application or committed reprehensible disqualifying acts since submitting the application. No one asks about good works.

The state’s goal is to exclude the bad but not necessarily admit the good. Naturalisation is the state’s final security check, an administrative border to traverse before citizenship (Aptekar 2016; Harper 2017). The state demands that the applicant swear (or affirm) to the tenets in the German Basic Law or US Constitution, respectively. This lack of interrogation about civic engagement or good citizenship is perplexing, as the state celebrates and expects citizen participation following naturalisation. The United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (2020) considers participation in the community as an obligation of citizens to:

- support and defend the Constitution;

- stay informed of the issues affecting your community;

- participate in the democratic process;

- respect and obey federal, state and local laws;

- respect the rights, beliefs and opinions of others;

- participate in your local community;

- pay income and other taxes honestly – and on time – to federal, state and local authorities;

- serve on a jury when called upon; and

- defend the country should the need arise.

The German government declares that civic engagement is ‘the backbone of our society’ and that civic engagement and public service are ‘essential for individual participation, social integration, prosperity, cultural life, stable democratic structures and social ties’ (BMI 2020). The citizenship and naturalisation proposal from the Social Democratic–Greens–Free Democrats coalition, the first new government in the post-Merkel era, may bring some recognition for participation.2 The (non-binding) coalition programme proposes easing naturalisation eligibility requirements (language requirements and dual nationality) by appreciating the contributions (‘lifelong achievement’) to Germany and the structural barriers impeding naturalisation for long-standing immigrant guestworkers (the Gastarbeiter generation). The idea of assessing integration and the value of contributions is not new. Austria, Denmark, France, Germany and the Netherlands have civic integration tests. The UK floated a scheme in 2010 for ‘earning’ citizenship through volunteering, labour, language acquisition, citizenship tests, etc. The German construction Staatsangehörigkeit erwerben (to earn or acquire citizenship) already reflects this reality linguistically.

There is a functional expectation of future civic engagement practices without any previous history. Naturalisation requirements do not consider how immigrants imagine themselves as citizens or demonstrate citizen behaviour. Aside from being law-abiding residents, not engaging in extreme politics and (in the US) not becoming public charges, the state tolerates non-citizen-immigrants and makes few demands. There are few expectations of any kind for permanent residents, including those rejected for naturalisation or who do not meet eligibility requirements.

My PTA experience and research findings suggest that diversity, citizenship and civic engagement interactions are complex. The variations in the idea of civic engagement are claims to rights and forms of activity that are explicitly outside those recognised by the institutions. The state-dominant narrative of immigrant ‘integration’ that frequently shapes policy and research agendas often discounts the dynamic dance of inclusion and exclusion which morphs people, conditions and their relationships as they interact. This narrative often lacks portions of the spectrum of immigrant perspectives, like immigrants rejected for naturalisation or who do not meet eligibility requirements.

Methods

This article is part of a larger project on understanding citizenship, drawing on a dataset of 150 one-hour interviews with permanent residents and naturalised citizens in New York and Berlin in 2004–2010 and 2016–2020. Study eligibility required that participants held permanent residency (US legal permanent residency (LPRs, ‘green card’) or its German (roughly) equivalent (unbefristete Aufenthaltserlaubnis), were able to communicate in the country’s dominant language, had completed at least secondary education and had lived for at least five years in the country. These items were selected to match state-preferred criteria for citizenship: labour-force age, legal status, language competency, educational achievement and signs of settlement.3 I made initial contact through postings and outreach through community-based organisations (CBOs) and then snowballing. Discussions4 were convened in CBO offices, cafés or an interview suite. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and coded. Using an inductive method of constant comparison (Corbin and Strauss 2014) in different rounds, I explored the emic experience of categorisation, liminal status, hierarchy of status and precarity of permanent residency. I interrogated differences over time. I coded the interview transcripts using Atlas.ti (a qualitative analysis programme) to uncover key themes for the dynamic interviewing process until theoretical saturation transpired. Throughout, I wrote dynamic theoretical memos about themes and mapped their relationships. I formally and informally shared my findings with colleagues, examining how immigrants imagine and practice citizenship. The project followed the ethical standards for human research in accordance with the CUNY Institutional Review Board.

A key element of interpretive work questions researcher biases in data collection and interpretations. I am a US-EU (Republic of Ireland) dual national whose immigrant and refugee ancestors hailed from six different countries. I grew up hearing stories about immigrant settlement in New York. As an adult, I learned German and worked in Berlin as a Robert Bosch Fellow. Thus, I have some first-hand experience of the kinds of interaction with the state, natives, co-ethnics and others discussed by my interview partners. I married an ethnic German immigrant to the US and vicariously lived experiences described by my interview partners through him and my dual-national children. My positionality offered a unique purview as both an insider and an outsider. Commonly, my interview partners remarked that I was ‘non-threatening’ and ‘easy to talk to’. I attribute this to my appearance as a middle-aged, phenotypically ambiguous, cis-gendered woman. I believe my interviewees spoke candidly since many recounted painful or embarrassing events. Like Fuji (2010), I recognise that people sometimes inaccurately retell stories and considered this in analysis.

Naturalisation, citizenship and engagement

How people viewed ‘being a citizen’ (meaning, here, naturalising and experiencing what naturalisation would provide) affected civic engagement. Effectively, there were three main perspectives on citizenship. People could be political by nature, benefit-seekers or claims-asserters.5 In all cases, how they perceived what naturalisation would yield shaped their civic engagement. Importantly, thoughts about participation were the same regardless of what I will call their citizenship condition (i.e., whether they had naturalised, were ineligible for naturalisation or had been rejected for naturalisation or had no interest in it). As I will show later, actions differed by citizenship condition. Those who were political by nature perceived naturalisation only as a way to escape governmental bureaucratic interference in people’s private lives – i.e., to facilitate border-crossing and eliminate visas. With or without naturalisation, they joined clubs, donated money, demonstrated, etc. In contrast, the benefit-seekers perceived citizenship as a path to economic and social benefits – better jobs, apartments, spouses, sex partners and scholarships. They were unlikely to engage civically in the receiving or sending country except for limited activities (one-time event attendance, demonstrations, charitable donations, neighbourliness, remittances, etc.) Citizenship provided no connection to community life. Any participation transpired for social or justice reasons but only if engagement did not compete with their main focus – which was to earn money, gain an education or care for their families. A third group, the claims-asserters, perceived citizenship as state compensation for immigrants’ dull, dirty and dangerous work or risk-taking when opening businesses. For them – whether naturalised citizens, permanent residents who could naturalise or those rejected from or ineligible for naturalisation – their labour sufficed as their contribution to the receiving state. They participated in events or groups with friends as social actions or worked to get benefits on behalf of family members. They were not motivated to engage in politics or civic affairs. Again, their labour was their contribution to the country and they saw no reason to give more through political participation.

Naturalisation affects modes of civic engagement

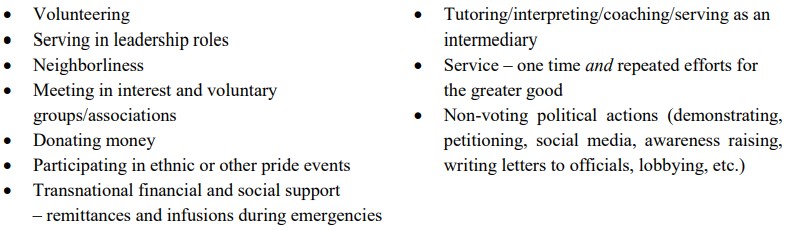

A person’s citizenship condition did not affect thoughts or opinions about naturalisation or what it would yield. What did change was how actions were performed, meaning that naturalisation did not entice joining groups, helping neighbours or performing any action shown in Figure 1. People were as civically active both before and after naturalisation (if it transpired), unless some extraordinary event, a Zeitgeist, new personal or professional connections or their life circumstances changed. However, naturalisation psychologically buttressed senses of self and altered immigrants’ mode of civic participation. Naturalised citizens feared expressing an opinion publicly as permanent residents but, once naturalised, they spoke freely. Formal citizenship enabled public speech. Permanent residents – trying to naturalise, unable to naturalise and not wanting to naturalise – felt constrained about speaking their minds or making demands on government, thus matching the naturalised citizens’ thoughts. However, their fear did not prevent participation, even in protest activities! Without citizenship, people might attend a demonstration by mixing in with the crowd. Once naturalised, they felt empowered to move to the front, to see and be seen. This behavioural change rationale is described as no longer fearing deportation, as evidenced by this German naturalised citizen from Gambia

I was always politically involved. I was political in Gambia and then, even when I came here. I had to be. I still am. I have always done stuff… Community service… and politics, that’s normal. Part of life, you know… Before I was a citizen, I would go to a demonstration. I always went. All kinds of reasons. But I would stay in the back. I was afraid. I wanted to be there but hoped that no one would see me. But now, I stand in the front. I am not afraid. I will even carry a sign. [laugh] I will hold the banner and stand in the front. I am not afraid now… Now that I am a citizen, I am not afraid of anyone.

In contrast, the fear of losing everything curtailed participation. Immigrants who imagined citizenship as an intangible benefit to improve the quality of their lives and those who felt that citizenship was the reward for their labour, appraised the potential risks of political action as too dear. No idealistic or indirect goal was worth deportation or familial dissolution. One US permanent resident from India stated:

Most immigrants are not wealthy people. Some came from real poverty. So, if they lose something, they lose a lot. I think, deport me if you must but, for many, it’s not like that. When you have less to lose, you can afford to do things that may jeopardise everything you worked for.

The natural community-joiners engaged regardless of risk or citizenship status as it was intertwined with their identity.

Of course, civic participation is not universal. The German government reports that about 40 per cent of the population is civically involved (BMI 2020). Commonly, people lack interest, exposure or free time. Negative views of home-country politics dampened participation. Other interests in sports, hobbies or family life take precedence. City life, satisfying basic needs or servicing remittance obligations exhausted some. Others lamented being too linguistically or culturally disconnected to grasp local issues. Permanent residents who had no interest in naturalising often wistfully revealed that their lives were ‘elsewhere’, in the origin country, as the locus of their lives. Except for one-time donations or helping neighbours locally, mobilising for civic actions and remitting to home countries for emergencies or ongoing support were origin-country exclusive.

Defensive citizenship – when citizenship is not enough

This research concurs with the literature (Chen 2020; Coutin 2003; Della Puppa and Sredanovic 2017; Godin and Sigona 2022; Harper 2011; Sredanovic 2022; Singer and Gilbertson 2003), that immigrants can perceive citizenship as a defensive mechanism protecting them from the state. Interview partners described their lives as precarious, rife with fears of deportation, family dissolution, loss of standing, time, financial investment and honour. Defensive citizenship goes beyond the psychosocial experience of ‘anchoring’ (Grzymała-Kazłowska and Brzozowska 2017: 104) or a search ‘…for footholds and points of reference which allow individuals to acquire socio-psychological stability and security’ (feeling safe and free from chaos and danger) and to lead meaningful lives in the new country. In the different rounds of interviewing, the immigrants in New York and Berlin differed in their perception of the degree to which naturalisation provided protection. The fear of deportation remained highly salient among the Berliners, regardless of the legal ‘rights to remain’ (Bleiberecht) held by all permanent residents. An artist, a German resident from Iran who was too poor to qualify for naturalisation, lived in perpetual fear of familial dispersal:

I would only become a citizen because it would make us sure to be together. I want my children to stay with me, for me to be with them. That is only sure, is the only way, if you are citizens. That is what makes me afraid. I never thought about citizenship, except for that one time. [Worrying about family deportations, she tried to apply but did not meet the income requirements.] After that, never. But now, I think, I am old. I want to be near my children. They can separate us. Make me leave. And then what? We are not a family any more.

Naturalisation provided a protective shield against the state, as stated by this German naturalised citizen from Gambia:

With naturalisation you have a few more rights… I can’t be thrown out. I feel good. I won’t be thrown out. I am relaxed. Nothing can happen to me now.

First-round interviewing in New York revealed fears of state capriciousness vis-à-vis immigrants motivated many immigrants to naturalise. Naturalisation connected immigrants to the state and secured their rights within the state. This US LPR from Afghanistan admits that:

If I have a green card, I am scared. I have nobody over there to defend me. Maybe the government will one day say ‘This is not your green card’. Then what will I do? I came here for the whole life. I don’t want to go back to my country. I respect the law, culture, tradition and so I have to become a citizen. To feel more the good here. If you’re not a citizen, people ask you ‘Who are you?’ If I am a citizen, I felt inside that I am strong, inside and outside. When I become a citizen, I can defend myself... I will be just like other American citizens. No difference between me and US citizens. Abroad, they will look at me like American citizen. If I am American citizen, I have equal rights. I will be the same Hassina [pseudonym] but I will be ‘Citizen Hassina’.

Once naturalised, the state conferred legal and political integration, rendering immigrants ‘safe’ among the community of citizens. Even when immigrants suffered discrimination or xenophobia and felt on the periphery of society, once they presented passports or other citizenship documents, they reported being treated ‘like other citizens’.

In a fundamental shift, this perception of citizenship-as-protection and citizen-community membership morphed after 11 September 2001, as they reported that all people, native and naturalised citizens alike, were suddenly suspect. Voicing opinions and protesting became dangerous for all citizens regardless of status as the government acted undemocratically, as this US-naturalised citizen from Ecuador claims:

It’s true for all citizens… So you see the people getting illegally arrested… Instead of promoting freedom for the protesters, like they should, because it’s your right, [the police] arrest you. These people were just exercising their right. We’re getting to a place where it’s like a totalitarian state and there is no way anymore to express my views. So, why volunteer if the government doesn’t allow you to voice an opinion or back something you believe in?

Immigrants naturalised into the state. However, state–society relationships have altered considerably in the US. Naturalisation may have protected immigrants against deportation but not against state actions because no citizen was safe. This is interesting because the immigrants perceived themselves to be entwined with citizens. In the subsequent round of interviewing in 2016–2020 this changed. Citizenship progressively lost its protective value. Similar to what Chen (2020) describes an ‘enforcement era’, US citizens recounted government officers subjecting naturalised citizens and their US native-born children to arbitrary actions. They asserted that immigrants were no longer grouped among the community of citizens but politically and socially classed among all immigrants (both legally and illegally present) and (tinged with racism) with deemed suspect co-ethnic (lower-status) citizens. Immigrants lamented the inability of locals to distinguish them from native-born minorities sharing similar physical traits, as experienced by this US-naturalised citizen from Zambia:

It’s very complicated here. I get lumped in with everyone else… confused with African-Americans… but our way is very different from the Blacks here…

This issue was exacerbated among the immigrants interviewed in later rounds, during the Trump administration. The value of citizenship as a protecting element declined further, according to another US-naturalized citizen from Zambia:

People denied it. Lots of people. Once the travel ban6 came in you’re not safe, even the citizens. Everyone’s not safe.

The fact that anti-immigrant policies officially targeted only non-citizens was immaterial. In contrast to earlier interviewing, both US-naturalised citizens and permanent residents felt unsafe, regardless of their citizenship status. The precarity of being immigrants trumped any security from being citizens: loyalty and belonging were questioned. It is unclear if this sentiment is temporary. Among the German group, Covid-19 limited recent access to the field; however, limited interviewing from 2015–2017 (thus after the 2015 influx of refugees) revealed a new palpable fear of burgeoning anti-immigrant sentiment, regardless of their time in Germany, citizenship status or ability to naturalise. In contrast to the US experience, the interviewees asserted that the state was not peddling xenophobia; nevertheless, it was also not providing xenophilia for them. They lamented the inefficacy of the state’s actions to help long-resident co-ethnics and criticised the state’s ‘open door’ and services for incoming asylum-seekers that were not offered to their (pre-1973 guestworker) families in Germany. There was a palpable concern about the growth of nationalist far-right actors. As one German-naturalised citizen from Turkey explained:

My passport doesn’t protect me on the street. No one sees it... It works at the [civil service] offices. I have to show it.

Critically, citizenship might provide safety from the German state but not from members of xenophobic organisations. Interestingly, none of the interview partners expressed any difference in their civic engagement practice, despite the increased precarity.

Immigrant thought on civic engagement

The literature on civic engagement generally comprises formal practices in organisational membership and leadership and performing social service, activism, tutoring and functionary work (Perez et al. 2010). Interviewees defined civic engagement as being both broader and narrower than these categories. Following findings from the inductive research process, interview partners defined civic engagement expansively to include community7 service and participation, volunteering, leadership, philanthropy, membership in social, neighbourhood, political or faith-based organisations with one-time (or multiple-time) actions that are intended to advance, improve or sustain community life (Figure 1). On the broader side, they constructed purposeful lives through neighbourliness and community engagement. They understood voluntary actions as purposive activities that offered the propensity for community well-being and opportunities for socialisation. Common political-science usage of terms do not always match the scopes of the actions which the interview partners described. I suggest they/we are still developing a vocabulary to describe the spectrum of ‘acts of citizenship’ (Isin and Nielsen 2008) that embody being a part of the body politic. Their thoughts, opinions and practices allow us to reconceptualise what citizens are, what naturalisation yields and what civic engagement can be (I avoid the ‘good citizens’ moniker here to avoid decrying non-participants as ‘bad citizens’).

Figure 1. Modes of civic engagement

|

|

“‘(C)ommunities of practice” are like “face-to-face units of sociality that immigrants come to experience a sense of belonging and citizenship”’ (Brettell and Reed-Danahay 2011: 79). For example, neighbourliness is a practice of citizenship and part of normal life, says this German-naturalised citizen from Syria:

I can’t just sit on the bus and let an old man stand. Or an old lady. And that we have, that I have it… in me, and so on, [it’s] in us. That is everyday life. That is engagement, that is every day with us…

Providing neighbourly care is civic engagement when modesty is perceived as an important purposeful, person-to-person service to the community. Here, engagement is a social justice corrective action remedying a non-responsive state. Like the above interviewee, the women I interviewed frequently recounted this kind of engagement:

There are so many ways to become engaged with the community. For example, you cook something and share it with the poor (but in secret, so that you don’t shame the people). You don’t go and say ‘I am here to help the poor!’

Women tended to discount their parent–teacher association (Elternvertretung) participation as parental behaviour rather than active citizenship. They could voice opinions but not be perceived as aggressive by natives and immigrants alike. Fear that political views endangered their own or family members’ status and decried as inappropriate behaviour among co-ethnics was ignored because mothers are obliged to advocate for their children, as this German-naturalised citizen from Turkey explained:

[Baking for a bake sale] was just something we did for the children of the school, to make sure that they got a good education, that the school was responsive to them. You know the schools don’t respond to the needs of our children.

Actions and donations were intended to generate social justice. Charitable donations were modest (even considering the interview partners’ incomes) and aimed to correct social wrongs and, the most often, were a one-time donation outside of (rich) receiving societies, as this next interviewee from Turkey, this time a permanent resident in Germany, states:

I gave some money once, but not for Germany! [points and grimaces] You have enough here. Once, my brother was working on a day campaign to raise money for Africa. For the poor people there and then we should pay what we could. I did that once for Africa, that poor children there should have something to eat.

Narrating the self as responsible for others expresses power and connectedness, whether locally or transnationally. It reflects continuity in migrants’ lives: they are never divorced from their previous selves nor are they exclusively part of the new state. Times of migration exist simultaneously, consecutively and entwined. Migrants ‘do not leave their origins and pasts behind; they take them with them; and by maintaining their networks, they begin to act as conduits between the two and more nations where they have connections’ according to Koopmans et al. (2005: 109, as cited in Salamońska, Lesińska, and Kloc-Nowak 2021). Through civic engagement, remittances for well-established immigrants solidified political, social and economic connections between sending and receiving societies. The translocal and the transnational meld, according to a US-naturalised citizen from Greece:

If I had money, I gave it to the Church. I gave money for Greek journals, to dances and sports teams. To develop ethnic identity. Soccer clubs to help boys play soccer. I am a member of this group, it’s a social club, just Greeks. We talk. Play cards. We sponsored sports teams to get them to come to America and play. You have to help. That’s your country!

Only those with firmly established transnational practices continually remitted. For the rest, one-time infusions for natural disasters to their sending communities served as financial displays of ‘civic engagement’.

Narrower perceptions of civic engagement

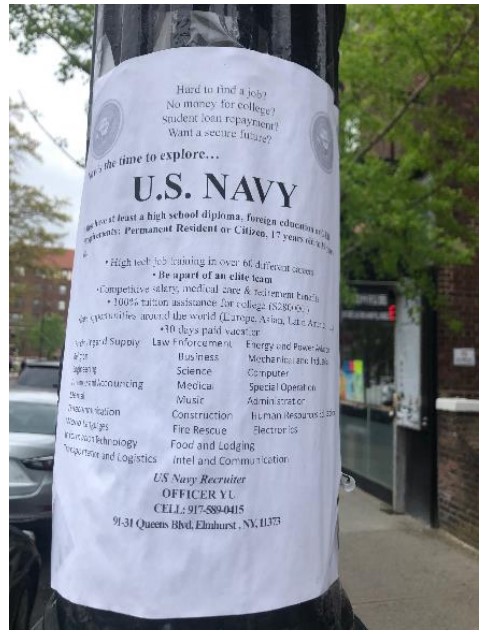

On the narrower side, the scope rarely included military service or ‘caring professions’ (i.e., healthcare providers, first responders, teachers, etc.). Even public-service workers described their contribution as a job, identity, vocation or link to other people but not as a connection to the state or society or an expression of good citizenship. Healthcare workers and military personnel are paid for their service regardless of their intentions. Recruitment efforts recognise these multiple objectives, as shown in Photo 1 for the military recruitment of US LPRs and naturalised citizens. Historically, military service and citizenship intertwined8 and legal bars to service were rationales for exclusion from citizenship (Bredbenner 2012). Now, military service is service but a job – not conscripted – and connections between service obligations and citizenship rights are thinner. Increasingly, military service is not perceived as an ‘…exceptional form of public service (that deserves) commensurate rewards’ (Ware 2012: 234). Service members may be hampered from applying or ridiculed for gaming naturalisation as compensation (Ware 2012). Ironically, at one time the idea of citizen soldiers and public service in the national interest was at the core of modern citizenship (Bredbenner 2012). During the Covid-19 pandemic, residents lauded healthcare workers as saviours. The ‘war on terrorism’ and Covid lockdowns morphed civic engagement boundaries in the public discourse emphasising military service (especially in the US) and first responder/healthcare providers (in the US and Germany).

Photo 1. Navy recruitment poster for permanent residents and citizens

[©Robin A. Harper] New York City 2021.

For some, the military is service and a job, as a US LPR from Jamaica explained before deploying to Afghanistan:

There’s nothing better for me than being in the army! I don’t worry about anything. My rent is paid. My family has health insurance. Everybody eats. The army takes care of my family. Everything is taken care of.

To this low-income serviceman, the military was his life – not a job or emotional connection to the state/nation. Deployment9 eliminated day-to-day worries about supporting his family. This service-as-locus-of-life sentiment was not unique. Like this US-naturalised citizen from India, immigrants across the socio-economic spectrum and ethnic background described their jobs as their vocation, comfort and support

‘All I ever wanted to be was a doctor. I studied here so that I could be a doctor. It’s how I make my living and it’s who I am’.

Paid activities represent a fraction of potential civic engagement. Unpaid community-based activities, like those promoting social and political change or rooted in civic well-being, may be the initial or primary form of civic or political action available to immigrants, as most democratic states rarely bar immigrants from civic participation. Initial queries about participation in civic activities yielded: ‘I never do that’ or ‘I don’t have time for that’. However, once discussing their children, their workplace or religious institutions, a flurry of explanations poured out about coaching teams, baking sales, providing food for sick neighbours, tending to local environments (picking up rubbish on pavements, sweeping streets, etc.), donating money, remittances, serving as interpreters/translators, signing petitions, protesting or demanding services. Contrary to their initial statements, their descriptions revealed that they did ‘do that’ and ‘had time for that’. Regular participation and organised groups and activities, however, were off-putting. The infrequent civic actions still provided an entrée into native, co-ethnic and immigrant local communities and meaningful modes of socialisation, while building skills and acquiring social capital. Even when performative citizenship did not make demands on the state or political arena, it modestly made actions for better lives.

Few interviewees practiced formal organisational membership, leadership, etc. (Those few who did engage with formal organisations historically had participated in their home countries and/or were stalwart ‘community-affairs-joiners’). Regardless of citizenship status or rejection/lack of interest in naturalising, most participated through a pastiche of independent, quotidian, person-to-person, one-time actions for the sake of interpersonal relationships and community betterment such as informal leadership, participation, philanthropy, one-on-one caregiving, etc. They developed connections, knowledge about community issues and how things work, social capital, identity, self-esteem and demands-making skills through interpersonal relations. Expressions of connection to a unit larger than oneself, even if not in a formal structure or as a formal citizen, provide opportunities for social learning, social agency and lived experience (Brettell and Reed-Danahay 2011).

Citizenship perspectives change how immigrants participate

Immigrants knew about opportunities for participation but worried about repercussions. They rattled off names of organisations, demonstrations, opportunities for donations, etc. but eschewed formal organisational membership, as they feared real or imagined threats of deportation from the receiving state and reprisals from home-country political factions and governments.10 Retribution loomed large in their thoughts, especially for those considering return migration, regardless of citizenship status. Naturalised citizens recalled fears as permanent residents and on-going concerns for non-naturalised family members. Lacking naturalisation constrained organisational civic participation, according to this German-naturalised citizen from Turkey:

After naturalisation I trusted myself more. Before, I was very reserved about getting involved in political affairs. Before, I was really afraid of repression by the Turkish state. Even here… (I)t would have been used against me. By the Ausländer11 office, it would have made some problems… (Now?) When I want to do something then I don’t have this fear any more that I need to protect my immigration status or something. The fear is no longer there. I have equal rights before the law just like all other Germans. Only if I commit a crime can they do something to me but not because I am Ausländerin. That’s what I mean.

Civic engagement citizenisation catalysed permanent residents to naturalise, teaching them how to make demands on the state. A US LPR from Nigeria recounted how a chance encounter with an unscrupulous taxi driver convinced her to naturalise:

There is no real difference to me between being a permanent resident and being a citizen. Look, there are practical differences, external things that change. When I am a citizen, I think I will feel a certain sense of entitlement and, maybe, like I am a real American... I had this experience in a taxi…The driver wasn’t paying attention to what I was saying, driving all over the place. So, I wrote a letter to the [Taxi & Limousine Commission]. They gave me a court hearing… That is what America does: I am viable!

She applied for citizenship shortly thereafter. Her self-narrative exposes evolution from subject to citizen. Practice in citizenship emboldened her to claim her right to citizenship, something she had not previously considered. Local community life informs how and whether immigrants civically engage. However, non-citizens may perform citizen acts precisely because they are part of the community, even when they are not members of the state. A German permanent resident from Turkey (financially ineligible for naturalisation and thus expected to have little interest in the long-term in the receiving society) explained that, even if immigrants came exclusively for money, over time they became enmeshed in the local (even if not the native) community:

The Germans think we are only here for the money. They think we came only for money and we stay only for money. We are only here for money and work. But not that we want to be here. And it’s not true. It’s really not true. People came for the money, maybe. But that’s not why they are still here. Now we have families here, our children are here. We have lived here for a long time.

His thoughts echo a critique of Putnam (2000, 2007) in Portes and Vickstom (2011) that people are already participating through their labour, daily living interactions, etc. Rather than thinking that the expected naturalisation spurs participation, the converse is also possible. Putnam, Portes and Vickstom (2011) argue, ignored directionality and what was actually generating what: Do citizens make engagement or does the engagement make citizens? These findings suggest that the latter is possible when the definitions of engagement depend on immigrants’ perspectives.

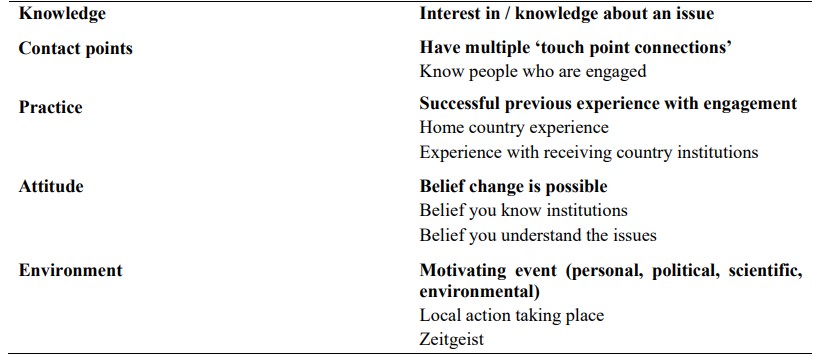

What promotes civic engagement?

There was a wide spectrum of political interest among those interviewed. People expressed intense, moderate and even no interest in political affairs. However, interest alone was not sufficient to promote action. Immigrants’ civic engagement depended on having community contacts, knowledge, practice, engaged friends, attitude and environment (Figure 2). Immigrants were mobilised or recruited through long-term interest, circumstantial opportunity or a catalyzing event. Very few engaged independently without a connection to others already involved. Following Bretell and Reed-Danahay (2011), the more points of connection that people had through school, employment, religious institutions, unions, etc., the more frequently they participated, as they had multiple opportunities, contexts for participation and formal structures to join.

Figure 2. Necessary elements for civic engagement

Interview partners ranged economically from cleaners and cashiers to businesspeople, artists and doctors, etc. Their participation does not seem to be related to income levels. Of course, some actions are more time- or financially intensive than others but, overall, any participation was informed by interest, situation, knowledge, Zeitgeist and knowing people who were already engaging. Whether this is generalisable to other contexts and times would require further inquiry.

Initial participation was frequently associated with a motivating event, i.e., difficulty getting help for a disabled child in school, discrimination in housing or employment, unpleasant neighbourhood conditions, violence or natural disaster in the sending country, etc. This first experience provided knowledge, social benefit and connections to others. People made new friends through collective action, spurring subsequent activity through private voluntary organisations, community groups, social clubs, sports teams, etc. Once people met people through one community action, they joined others. If they had social success in engaging, they might be drawn into more formal organisations with more-public profiles. Positive and intense first experiences led to subsequent engagement. One-time or low-commitment efforts (petition signing, one-time donations, etc.) were not springboards for subsequent participation. People had to believe that change was possible – that their actions could promote change – and they understood how institutions worked. Civic volunteerism through social connections catalysed subsequent activities, as illustrated by this German-naturalised citizen from Turkey:

‘Everything began with the earthquake. Before, I never cared. Then, I felt like I had to do something!

Similarly, a US LPR from Haiti observed:

The first time? Trayvon Martin’s12 murder. I couldn’t just sit home. I had to go protest. I haven’t stopped’.

Participation in civic groups and voluntary organisations can encourage subsequent social and political action (McFarland and Thomas 2006; Terriquez 2015). Participation can generate communal identities producing social benefits, especially when people engage through community service, representation and public forums (McFarland and Thomas 2006; Terriquez and Lin 2020). In this way, engagement shapes and is shaped by citizenship.

Civic engagement is not a given. Home-country civic or political experiences were both a catalyst and a barrier to participation. Previous collective action provided skills and knowledge for engagement in the new state. Those familiar with negative repercussions from home-country participation were more hesitant to engage civically, especially as LPRs, citing fear of governmental repercussions or family dissolution. Association membership is often specific. Being a member in one context did not always engender carryover. Despite declines in organisational behaviour in both countries, private voluntary organisations (German Vereine) are part of normal social life and public-problem resolution. Respondents perceived non-immigrant-based groups to be less welcoming to non-natives and, on the whole, preferred immigrant- or religious-based groups. In both earlier and later interviews in Berlin and New York, immigrants participated in demonstrations and sometimes lobbying, with younger people reporting street protesting against war and income inequality and then, later, against racism.

Perspectives on civic engagement and naturalisation

From the state’s perspective, naturalisation is the formal transition from foreigner to citizen-member. The literature on citizenship presents citizenship as membership, legal status, identity, rights and obligations and good community behaviour (Joppke 2010). However, as Bosniak (2000) reminds us, concepts are both labels and signals. Concepts both describe and legitimate social practices, granting them politically consequential recognition. The law treats citizens and non-citizens differently, as citizens are preferred, safe, insiders and all others are, by default, suspect and assumed to be dangerous. The state hierarchy of preferential treatment is an intended perk of citizenship; without it, citizenship is meaningless (Oldfield 1990). The disparate treatment in law generates alternate life trajectories for citizens and non-citizens (Shachar 2009), allowing non-citizens to sometimes be treated as less than human (Oldfield 1990).

The state does not demand or pursue immigrants toward naturalisation or to reapply if rejected. Immigrants must initiate requests for citizenship. Engagement should follow naturally, as it is the demand experience (also a form of engagement), not the legal status, which makes citizens.

From the state’s perspective, non-citizens are functionally different from citizens and naturalisation imposes a meaningful border mediating permanent residency and citizenship (Aptekar 2016; Harper 2017). Increasingly, states employ dynamically morphing national borders to advance state policy and benefit citizen-insiders while excluding non-citizen-outsiders (Shachar 2020). Immigrants are, however, the same people before and after (if there is a naturalisation), entwined in a legal fiction. From the state perspective, naturalisation should empower permanent residents as they initiate the naturalisation process. However, do immigrants’ imaginations include this demarcating metaphysical border or a continuum? Do LPRs who were rejected or those who never applied for naturalisation (because they were not eligible or did not want to apply) civically engage like LPRs who can naturalise or naturalised citizens? Perhaps ‘good citizenship’ and citizenship are not intimately connected from immigrants’ perspectives. The immigrant perspective reveals the limits of the legal fiction. Immigrants’ scopes of actions reimagine, elaborate, contract and rewrite what citizenship and civic engagement can be. In broadening and narrowing the definition of civic engagement, immigrants are excluding problematic items, while valuing contributions overlooked by the state and receiving society. In so doing, they develop a new definition and self-value as community members regardless of the state’s determination of their belonging, attachment or inclusion.

Conclusion

Immigrant imaginations of civic engagement are broader and narrower and their conceptions of citizenship are sunnier and darker than the thin state expectations. On the positive side, civic engagement is the everyday practice of citizenship. Naturalised citizens and permanent residents did not wait for states to tell them to engage civically but, to varying degrees, helped their communities and voiced opinions. Migrants’ actions can be perceived as preparation for their ‘future selves’ (Stingl 2021), rendering them ‘citizens-in-waiting’ (Motomura 2006). Naturalisation did not motivate participation. Lack of citizenship may have dampened the vibrancy of participation. However, engagement offered an opportunity to exist outside of their immigration status – that is, to be the giver and not the recipient of help; to stand up for their children and those less fortunate; to be a social person connected to others in their ‘community’ (however personally defined); to support issues of interest financially, socially, politically and emotionally with their thoughts, money and bodies as a mechanism to escape their migrant status and to feel valued as a human being.

Naturalisation did not change whether people participated but how they participated. Participation depended on individual interest not citizenship status, as naturalised citizens and those who wanted to naturalise but could not or had been rejected described their civic engagement similarly. Citizenship allowed migrants to feel safer and thus be able to visibly voice opinions in public protests or make demands on government. If people believed that change was impossible or too costly, they ceased. Like the institution of citizenship, collective citizenship self-narratives are dynamic. Citizenship, at one time, made immigrants feel safe. This feeling is declining, as US national-policy approaches to immigrants are perceived as less welcoming and both German and US right-wing actors are emboldened to express xenophobia. These feelings of fear also affected and curtailed more political actions but did not affect non-political participation.

Immigrants perform everyday practices of ‘good’ citizenship to protect, care for and enrich community life, even when they shy away from terms calling them civically active. Rather, this quiet engagement works to reimagine what engagement can be and what a citizen is. In this way, the state’s imperator is largely immaterial, as immigrants may participate in the full spectrum of voluntary and civic engagement regardless of their citizenship status. Those who naturalised and choose to naturalise, those who choose not to, those who cannot because they do not meet the eligibility requirements or those who were rejected, all describe their scopes of engagement similarly regardless of citizenship status. Those who do not participate are making their own citizen choice. Nobody in a democracy is ordered to perform ‘good’ citizenship. They are merely exercising their rights not to participate. As the national political culture morphs, immigrant thoughts about how citizens are treated by the state or natives and other immigrants affect decisions about engagement.

Self-narratives of ‘citizen life’ (including protest actions, neighbourliness and all other civic engagement actions described in this article) reflect abilities to perform citizenship, not their legal or political status. In contrast to integration schemes that demand sublimation to national values (Kostakopoulou 2010), these self-definitions showcase participation without a shadow of the dominant culture and its racism, the discounting of widespread inequalities and the structural barriers to full inclusion. If, as Theiss-Morse and Hibbing (2005) assert, voluntary organisation participation and other civic engagement do not necessarily prepare people for or lead them to democratic action, then immigrants’ previous civic action is unimportant for future citizen lives. In this case, both the state’s expectations and the immigrants’ self-narratives are appropriate.

One aspiration for the findings of this research is to think about the fear that colours immigrant citizenship narratives. Their self-narratives about precarious LPR time and, increasingly, the alienation experienced by naturalised citizens, do not match state imaginations or expectations for citizens. Even those who are by nature civically active may become afraid and recoil from the public arena. If this happens for long periods, they may forget how to be civically viable. This dark view of citizenship – for native and naturalised citizens alike – suggests that, for immigrants, the state’s imagination for ‘integration’ culminating in naturalisation does not reflect their perspective at all. Citizenship is not a marker of belonging and civic engagement is not the process leading to attachment. Indeed, a state’s imagined integration regimes are not borne out by immigrants’ self-narratives. Further, there are concerns about the precarious nature of citizenship as a whole. Perhaps these findings can initiate consideration about what makes a citizen suitable when seeking ‘good’ citizens and how to make (non)citizenship less precarious? By not considering civic engagement practice in the naturalisation process, counting how people contribute to community life, voice opinions, make demands on the state or help their neighbours, the state may be excluding some possible full members to enrich democratic and community life, something the state expects of all citizens and celebrates as critical to democratic and community life. Immigrant self-narratives of citizenship and civic engagement can illuminate settlement experiences and perhaps inform new metrics and understandings of the whole citizenship experience.

Notes

- Immigrants’ means here ‘permanent residents’ – potential citizens – and ‘naturalized citizens’. Temporary and undocumented migrants were purposely excluded.

- The proposal was issued on 24 November 2021. Prospects remain unclear. See ‘Mehr Fortschritt Wagen’ Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit. Koalitionsvertrag zwischen SPD, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen und FDP. https://www.spd.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Koalitionsvertrag/Koalitionsvertr... (accessed 30 November 2021).

- There are no academic eligibility requirements for citizenship in either Germany or the US. I chose this list of preferential categories as it facilitated recruitment, comparison, and the states’ overarching intention. It is not a perfect proxy. However, in both states, there is an implicit preference for educational attainment even when there is no explicit requirement. For example, naturalization applicants must be literate, know about history and community practices, be able to study for examinations, and speak the national language, although in some cases people can receive a waiver. Further, both states have preferential categories based on exceptional educational/professional attainment.

- Interviews in Berlin were conducted in German. All German-English translations are mine.

- Additional citizenship frames are discussed elsewhere (Harper 2007, 2011).

- In 2017 the Trump administration imposed a travel ban for immigrants from certain countries. The Biden administration rescinded the order in 2020.

- Definitions of ‘community’ were broad: local, ethnic, transnational, national, religious, or neighborhood.

- In the US, LPRs may join the military with no expectation of naturalising. At times, people serving even one day could naturalise. Until 2016, citing security risks, even the undocumented could enlist. All male US citizens and all legally and illegally-present male immigrants between18–26 must register for the peacetime draft (The Selective Service registration form states: ‘Current law does not permit females to register). The Bundeswehr reports that despite some recent proposals, noncitizens may not join or serve in the armed forces in any capacity (private correspondence 4-28-2021).

- The US military operates both active-duty and reserve units (civilian ‘weekend warriors’). Increasingly, reserve units activate for overseas deployment.

- Some informants intimated clandestine activities but refused further elaboration, fearing retribution.

- Refers to the Immigrant Affairs office. Interview partners most commonly described themselves as ‘Ausländer’ (m) or ‘Ausländerin’ (f), meaning ‘foreigner.’ Germany began conferring birthright citizenship in 2000. Prior, a German-born life-long resident could still be an ‘Ausländer’. Despite ongoing official efforts to promote other terms it remains in the lexicon.

- An African-American teenager killed by a white vigilante became a cause célèbre, spurring the Black Lives Matter movement.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my interview partners in New York and Berlin for their generous gifts of insight and time. I would also like to thank Catherine Lillie, Maggie Laidlaw, Dr Doga Can Atalay, Professor Antonia Layard, Professor Umut Korkut, the participants in the May 2021 VOLPOWER workshop and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Any remaining errors are, of course, mine.

Funding

The author received no funding for this project.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID ID

Robin A. Harper  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2190-5135

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2190-5135

References

Aptekar S. (2016). Constructing the Boundaries of US Citizenship in the Era of Enforcement and Securitization, in: N. Stokes-DuPass, R. Fruja (eds), Citizenship, Belonging, and Nation-States in the Twenty-First Century, pp. 1–29. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Boersma S., Schinkel W. (2018). Imaginaries of Postponed Arrival: On Seeing ‘Society’ and Its ‘Immigrants’. Cultural Studies 32(2): 308–325.

Bosniak L. (2000). Universal Citizenship and the Problem of Alienage. Northwestern University Law Review 94(3): 963–984.

Bredbenner C. (2012). A Duty to Defend? The Evolution of Aliens’ Military Obligations to the United States, 1792 to 1946. Journal of Policy History 24(2): 224–262.

Brettell C., Reed-Danahay D. (2011). Civic Engagements: The Citizenship Practices of Indian and Vietnamese Immigrants. Redwood City CA: Stanford University Press.

BMI (2020). Die Bedeutung von Ehrenamt und Bürgerschaftlichem Engagement. Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat. https://www.bmi.bund.de/DE/themen/heimat-integration/buergerschaftliches... (accessed 8 June 2023).

Byrne B. (2017). Testing Times: The Place of the Citizenship Test in the UK Immigration Regime and New Citizens’ Responses to It. Sociology 51(2): 323–338.

Cantle T. (2005). Community Cohesion: A New Framework for Race and Diversity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Chen M.H. (2020). Pursuing Citizenship in the Enforcement Era. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Corbin J., Strauss A. (2014). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

Coutin S.B. (2003). Cultural Logics of Belonging and Movement Transnationalism, Naturalization and US Immigration Politics. American Ethnologist 30(4): 508–526.

Della Puppa F., Sredanovic D. (2017). Citizen to Stay or Citizen to Go? Naturalization, Security, and Mobility of Migrants in Italy. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 15(4): 366–383.

Fortier A.M. (2017). The Psychic Life of Policy: Desire, Anxiety and ‘Citizenisation’ in Britain. Critical Social Policy 37(1): 3–21.

Fuji L.A. (2010). Shades of Truth and Lies: Interpreting Testimonies of War and Violence. Journal of Peace Research 47(2): 231–241.

Godin M., Sigona N. (2022). Intergenerational Narratives of Citizenship among EU Citizens in the UK after the Brexit Referendum. Ethnic and Racial Studies 45(6): 1135–1154.

Grzymała-Kazłowska A., Brzozowska A. (2017). From Drifting to Anchoring. Capturing the Experience of Ukrainian Migrants in Poland. Central and Eastern European Migration Review 6(2): 103–122.

Hamann U., Yurdakul G. (2018). The Transformative Forces of Migration: Refugees and the Re-configuration of Migration Societies. Social Inclusion 6(1): 110–114.

Harper A., Kriegel L., Morris C., Hamer H.P., Gambino M. (2017). Finding Citizenship: What Works? American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 20(3): 200–217.

Harper R.A. (2007). Does Citizenship Really Matter? An Exploration of the Role Citizenship Plays in the Civic Incorporation of Permanent Residents and Naturalized Citizens in New York and Berlin. Unpublished PhD dissertation. City University of New York.

Harper R.A. (2011). Making Meaning of Naturalization, Citizenship and Beyond from the Perspective of Turkish Labor Migrants, in: Ş. Ozil, M. Hofmann, Y. Dayioglu-Yücel (eds), 50 Jahre Türkische Arbeitsmigration in Deutschland [50 Years of Turkish Labor Migration in Germany]. Türkisch-Deutsche Studien. Jahrbuch: 17–36.

Harper R.A. (2017). Deconstructing Naturalization Ceremonies as Public Spectacles of Citizenship. Space and Polity 21(1): 92–107.

Isin E. (2019). Doing Rights with Things: The Art of Becoming Citizens, in: P. Hildebrandt, K. Evert, S. Peters, M. Schaub, K. Wildner, G. Ziemer (eds), Performing Citizenship: Bodies, Agencies, Limitations, pp. 45–56. Cham: Springer Nature.

Isin E.F., Nielsen G.M. (eds) (2008). Acts of Citizenship. London: Bloomsbury.

Jones-Correa M. (1998). Different Paths: Gender, Immigration and Political Participation. International Migration Review 32(2): 326–349.

Joppke C. (2010). Citizenship and Immigration. Malden: Polity Press.

Koopmans R., Statham P., Giugni M., Passy F. (2005). Contested Citizenship: Immigration and Cultural Diversity in Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kostakopoulou D. (2010). Matters of Control: Integration Tests, Naturalisation Reform and Probationary Citizenship in the United Kingdom. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36(5): 829–846.

McFarland D.A., Thomas R.J. (2006). Bowling Young: How Youth Voluntary Associations Influence Adult Political Participation. American Sociological Review 71(3): 401–425.

Motomura H. (2006). Americans in Waiting: The Lost Story of Immigration and Citizenship in the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oldfield A. (1990). Citizenship and Community: Civic Republicanism and the Modern World, in: G. Shafir (ed.), The Citizenship Debates: A Reader, pp. 75–92. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Orton A. (2010). Exploring Interactions in Migrant Integration: Connecting Policy, Research and Practice Perspectives on Recognition, Empowerment, Participation and Belonging. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. http://dro.dur.ac.uk/9481 (accessed 8 June 2023).

Perez W., Espinoza R., Ramos K., Coronado H., Cortes R. (2010). Civic Engagement Patterns of Undocumented Mexican Students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 9(3): 245–265.

Portes A., Vickstrom E. (2011). Diversity, Social Capital, and Cohesion. Annual Review of Sociology 37(1): 461–479.

Putnam R.D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Putnam R.D. (2007). E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty‐first Century. The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies 30(2): 137–174.

Putnam R.D., Leonardi R., Nanetti R.Y. (1994). Making Democracy Work. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ramakrishnan S.K. (2006). But Do They Bowl? Race, Immigrant Incorporation and Civic Voluntarism in the United States, in: T. Lee, S.K. Ramakrishnan, R. Ramírez (eds), Transforming Politics, Transforming America: The Political and Civic Incorporation of Immigrants in the United States, pp. 243–259. Charlottesville VA: University of Virginia Press.

Ramakrishnan S.K., Bloemraad I. (eds) (2008). Civic Hopes and Political Realities: Immigrants, Community Organizations and Political Engagement. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Reed-Danahay D., Brettell C.B. (2008). Citizenship, Political Engagement, and Belonging. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Rosenstone S.J., Hansen J.M. (1993). Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America. Harlow: Longman Publishing Group.

Salamońska J., Lesińska M., Kloc-Nowak W. (2021). Polish Migrants in Ireland and Their Political (Dis)Engagement in Transnational Space. Central and Eastern European Migration Review 10(2): 49–69.

Sayad A. (1993). Naturels et Naturalisés. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 99(1): 26–35.

Shachar A. (2009). The Birthright Lottery: Citizenship and Global Inequality. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Shachar A. (2020). The Shifting Border: Legal Cartographies of Migration and Mobility. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Singer A., Gilbertson G. (2003). The Blue Passport. Gender and the Social Process of Naturalization among Dominican Immigrants in New York City, in: P. Hondagneu-Sotelo (ed.), Gender and US Immigration: Contemporary Trends, pp. 359–378. Oakland CA: University of California Press.

Sredanovic D. (2022). The Tactics and Strategies of Naturalisation: UK and EU27 Citizens in the Context of Brexit. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48(13): 3095–3112.

Stingl I. (2021). (Im)Possible Selves in the Swiss Labour Market: Temporalities, Immigration Regulations, and the Production of Precarious Workers. Geoforum 125: 1–8.

Theiss-Morse E. (2009). Who Counts as an American? The Boundaries of National Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Theiss-Morse E., Hibbing J.R. (2005). Citizenship and Civic Engagement. Annual Review of Political Science 8(1): 227–249.

Terriquez V. (2015). Training Young Activists: Grassroots Organizing and Youths’ Civic and Political Trajectories. Sociological Perspectives 58(2): 223–242.

Terriquez V., Lin M. (2020). Yesterday They Marched, Today They Mobilised the Vote: A Developmental Model for Civic Leadership among the Children of Immigrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46(4): 747–769.

Today with Hoda & Jenna (2021). George W. Bush Joins Daughter Jenna Bush Hager To Discuss Immigration, April 21. https://www.today.com/video/george-w-bush-joins-daughter-jenna-bush-hage... (accessed 8 June 2023).

United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) (2020). Citizenship Rights and Responsibilities. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/flyers/M-767.pdf (accessed 23 April 2021).

Verba S., Schlozman K.L., Brady H. (1995). Voice and Equality: Civic Volunteerism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ware V. (2012). Military Migrants: Fighting for YOUR country. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.