Chechen’s Lesson. Challenges of Integrating Refugee Children in a Transit Country: A Polish Case Study

-

Author(s):Iglicka, KrystynaPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2017, pp. 123-140DOI: 10.17467/ceemr.2017.08Received:

5 January 2017

Accepted:1 June 2017

Published:13 June 2017

Views: 35375

This paper examines migratory movements into Poland with a special emphasis on refugee mobility. In the past twenty years, almost 90 000 Chechen refugees have come to Poland, as it was the first safe country they reached. According to the Office for Foreigners data they constituted approximately 90 per cent of applicants for refugee status, 38 per cent of persons granted refugee status, 90 per cent of persons granted ‘tolerated status’ and 93 per cent of persons granted ‘subsidiary protection status’. However, a peculiarity of the Polish situation, confirmed by official statistics and research, is that refugees treat Poland mainly as a transit country. The author focuses on the issue of integrating Chechen refugee children into the Polish education system, as well as Chechen children granted international protection or waiting to be granted such protection. The results of the study suggest that Polish immigration policy has no impact on the choice of destination of the refugees that were interviewed. None of the interviewees wanted to return to Chechnya, nor did they perceive Poland as a destination country. Children with refugee status, which enables them to stay legally in the Schengen area, ‘disappear’ not only from the Polish educational system but from Poland as a whole as well. This phenomenon hampers the possibility of achieving educational success when working with foreign children, and it challenges the immense efforts by Polish institutions to integrate refugee children into the school and the local community. Both official statistical data and research results were used in this paper.

Introduction

The character of refugee inflow into Poland is of considerable significance, not only for politicians in the CEE region but also for those involved in the issues of immigrants’ integration. There are important lessons to be learned from recent experiences; lessons that challenge longstanding perspectives, especially in the light of the current immigration/refugee crisis in Europe.

This paper addresses the challenges relating to refugee mobility into Poland from the beginning of the 1990s until the beginning of the second decade of the 21st century. The bulk of asylum seekers entering Poland are Russian citizens of Chechen origin. The paper provides both legal and policy information on the framework of refugee integration in Poland. Furthermore, the author focuses on the issue of integrating refugee children into the education system and, more specifically, the integration of children granted international legal protection or waiting to be granted such protection. Drawing on both official statistical data (derived from the Office for Foreigners and Ministry of National Education) and research findings, the paper reports empirical results from the pioneering, qualitative study on ‘transit’ refugee children in Polish schools.1 Within the framework of the study, 45 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted in three main provinces (15 interviews in each region) where refugee centres have been established: Mazovian Province (central part of Poland), the Lublin Province, and Podlasie Province (south-eastern part). These provinces were selected as they have the biggest number of refugee centres on their territories. In each province, semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives of the Ministry of National Education, school headmasters, teachers, multicultural assistants, parents of refugees (of Chechen origin), NGO representatives and social workers.

According to the definition of integration contained in the Common Basic Principles for Immigrant Integration Policy in the EU (2004), integration is a two-way process of mutual accommodation by immigrants and residents of Member States. This process has a dynamic, long-term and continuous character. Under this definition, integration implies the receiving society’s respect for the immigrants’ rights to preserve their own cultural identity and integrity. On the one hand it requires receiving countries to show goodwill, which includes developing mechanisms and procedures to facilitate immigrants’ integration. On the other hand, immigrants, including forced ones, i.e. refugees, are expected to join and integrate with the social and political life of the receiving society.

The integration of refugees in a given society should not be analysed only from the perspective of labour markets but, especially in the case of minors, from schools as well. The significance of education policy for the integration of immigrants stems from a basic assumption adopted by a number of national education systems, which calls for ensuring equal opportunities for individual development and the acquisition of basic skills and knowledge and professional qualifications (Szelewa 2010). The integrative role of school education is invaluable, since it affects the individual at the moment when he/she is preparing to adopt the role of a member of society. One should note here that parents can integrate with the receiving society through their children’s school as well. The children’s school experience helps the parents to learn and understand the principles and values of the receiving society and – which is extremely important – the often unwritten rules of local community. In this way, refugee children become both a link to and mediators between their family members and the outside world.

However, refugee children, and more broadly children and youth under international legal protection, constitute a very special group. Very often they have had traumatic experiences that affect their daily functioning, also at school. Some have gaps in the educational process, and many, including teenagers, have no school experience at all.

The literature on the integration of refugees in education in both United States and Western European countries is vast (see e.g. Dryden-Peterson 2015; European Commission Library and e-Resources Centre 2015). As Black (2001: 57) notes, ‘the last fifty years, and especially the last two decades have witnessed both a dramatic increase in academic work on refugees and significant institutional development in the field’.

Since immigrants and refugees started arriving in Poland in larger numbers only after the 1989 geopolitical restructuring of Europe, national research on emerging new migratory patterns necessarily have a relatively short history. Indeed, the changes in mobility posed significant challenges for Polish migratory research and its rather inexperienced researchers (Iglicka 2002, 2010). As for the integration of foreign students in schools, studies have concentrated mainly on both social and legal challenges stemming, firstly, from the sudden cultural diversity and, secondly, from the implementation of EU directives in the national legal framework (Czerniejewska 2013; Gmaj 2007; Konieczna and Świdrowska 2008). The literature on the functioning of foreigners in Polish schools focuses most extensively on the situation of students of Vietnamese origin (Głowacka-Grajper 2006; Halik, Nowicka and Połeć 2006) or the situation of students–immigrants from the former Soviet Union countries (Konieczna and Świdrowska 2008).

Nevertheless, the phenomenon of refugees in Poland and their functioning at school has also attracted some attention of both researchers and NGOs activists in Poland2 (e.g. Chrzanowska and Gracz 2007; Ząbek and Łodziński 2008; Januszewska 2010; Łodziński and Ząbek 2010; Siarkiewicz 2001). Unfortunately, the most important work was done in Polish. This paper tries to fill the gap and present English language readers with the findings of the pioneering research into the challenges of refugee integration in Polish schools.3

Refugee and asylum seekers legal framework in Poland

As far as the legal framework for refugees and asylum seekers is concerned, until 1991 Poland had only granted asylum to people for a limited set of reasons, and most of those who received asylum were communists from Greece and Chile escaping Greece’s junta regime and Pinochet’s regime in Chile. After Poland ratified the United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol, in September 1991 the country amended the 1963 Aliens Act to formally establish a system for granting refugee status (Iglicka 2001). In accordance with the 1959 European agreement on the Abolition of Visas for Refugees, refugees in Poland are issued a travel document, a so-called Geneva passport. The document enables them to travel without a visa to other states that have signed the agreement.

Poland also started granting additional forms of humanitarian protection, e.g. ‘tolerated status’ and ‘subsidiary-protection status’ in accordance with the Qualification Directive.4 Subsidiary-protection status (which came into force in 2007) is for those who do not fulfill the requirements for becoming a refugee but who would be at risk upon returning to their countries. Tolerated status (which came into force in 2003) is granted in some cases after the person has been rejected for refugee or subsidiary-protection status.

All those granted humanitarian protection have a right to work and to start their own business in Poland. They have access to health insurance and free education and can eventually apply for permanent residence. Both refugees and people with subsidiary-protection status have access to integration programmes and social assistance. Only a few of these benefits, such as shelter, meals and financial aid in critical situations, are also granted to those with tolerated status.

As far as integration policy is concerned, Poland’s first integration programmes regarding the foreigners were launched in the early 1990s and targeted refugees from the former Yugoslavia. Since then, it has been within the competence of local regional governors to coordinate the measures for the integration of refugees in their regions. The main unit responsible for immigrant integration management at the national level is the Department of Social Assistance and Integration in the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy.5 This unit determines the whole area of social assistance. Therefore, immigrant integration is only a small part of its many activities (Iglicka 2014: 107).

Integration programmes are restricted to those who are granted international protection. The Individual Integration Programme, which the local/municipal family support centre runs, does not exceed one calendar year. During that year, participants receive cash benefits for living expenses and Polish-language classes. The programme also covers contributions to health insurance and the costs of specialised guidance services, finding accommodation, and social work activities. As of March 2008, these provisions have been extended to those with subsidiary-protection status.6

Indeed, Poland lags behind its western neighbours in regulating and developing services for immigrants (Bieniecki, Kazmierkiewicz and Smoter 2006). The government’s lack of interest in immigrants might well stem from Poland’s isolation during the communist era and the self-perception of Poland as ethnically and culturally homogenous (Iglicka and Ziolek-Skrzypczak 2010), though perhaps foremost from the fact that both the stock and current flows of foreign residents have remained relatively low by EU standards. Wrongly assuming that the inflow of foreigners depends on policy and not on the economic prosperity of a given country, the government has taken decisive steps toward reforming Poland’s migration policy.

The debate on the strategy was finalised in July 2012 when a document titled Migration Policy of Poland – the Current State of Play and Further Actions (MI 2012) was adopted by the Council of Ministers.7 The document was drafted after lengthy consultations with social partners, including NGOs (Iglicka 2014: 107).

This document is meant to serve as a basis for setting specific migration policy targets, drafting specific laws and other regulations, and promoting relevant institutions in the years ahead. It is the first migration policy document adopted by the government of Poland of such political importance, and with such substantive extent (Iglicka 2014: 107).

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the document is in fact all about immigration policy, in spite of the fact that Poland continues to be primarily a country of emigration (acknowledged and deplored in many public speeches by the highest officials), where foreigners not only constitute a tiny minority but the inflow from other countries is low and most likely will remain low in the near future.

The above prioritisation of migration policy goals and topics, despite the government’s concern with the continuing outflow of Polish people to other countries, reflects a tendency towards a ‘Europeanisation’ of government policy and a rather passive participation (from the national point of view) in the discussion on common EU asylum/relocation policy. On 14 September 2014, Prime Minister Kopacz spoke ahead of an EU summit on the refugee crisis, saying, ‘We will accept as many refugees as we can afford, not one more, not one less. I promise the Polish people that we will not show ourselves to be the black sheep of Europe’.8

However, in the October 2015 parliamentary election, the right-wing Law and Justice Party won the majority of seats, and official rhetoric took on a harsher tone under the new government. After the March 2016 terrorist attacks in Brussels, Prime Minister Beata Szydło announced that Poland would not accept any refugees under the plan. ‘I say very clearly that I see no possibility at this time of immigrants coming to Poland’.9

The strategy of Poland’s migration policy (MI 2012) was cancelled. The emphasis of a new policy is squarely on security. One conspicuous example of this attitude is the Polish government’s close cooperation in EU security issues. Frontex, the EU agency entrusted with coordinating border security, is based in Warsaw. One can also notice an increase in decision-makers’ interest in immigrants’ integration issues. They more actively started to offer commentaries and suggestions regarding the programmes implemented by the European Refugee Fund (EFR) and European Integration Fund (EIF) (Iglicka and Gmaj 2015).

The refugee population: main demographic and social features

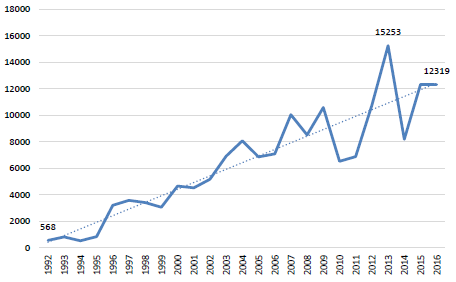

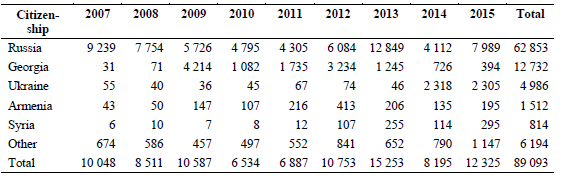

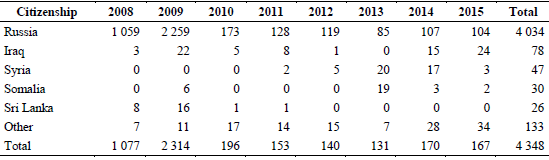

Poland has experienced a steadily increasing number of refugee applications from various countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa since the late 1990s, from just over 3 400 in 1998 to over 15 000 in the peak year of 2013 (see Figure 1). Over the last decade, the majority of applications came from Russia, most of them from the war-torn region of Chechnya (see Table 1). Prior to the year 2000 (during and after the first Russian-Chechen war from 1994 till 1996), the majority of the applicants were young single men who wanted to work in Europe and to build the basis of a new life for themselves and their families (Stummer 2016). The situation changed after the outbreak of the second war in 2004. That is when a lot of children and single mothers started to arrive, the majority coming from the Chechen capital of Grozny.

As Stummer (2016) stresses: ‘Officially, the second Russian-Chechen war ended in the 2009. Although the number of refugees has been getting lower year by year, thousands are still crossing European borders, mostly because of the brutality of the Kadyrov regime and the poor living conditions of their home regions. The biggest increase in the number of applicants arriving from the Russian Federation took place in 2013, when the German government agreed to introduce social benefits for refugees equaling the amount paid to German citizens’.

In the year 2013, Poland had taken 12 849 asylum seekers from the Russian Federation whereas in the preceding year the number of arriving applicants was 6 084, and in the year before it amounted to 4 305 (see Table 1). In the period after 2013 the number of applications dropped and it currently fluctuates around 12 000. As for asylum applications since 2014, Ukrainians now occupy second place.

Figure 1. Refugee applications in Poland, 1992-2016

Source: Office for Foreigners, Warsaw, various years.

Table 1. The number and nationality of persons who applied for asylum in the territory of Poland (top five countries) (2007-2015)

Source: Office for Foreigners, Warsaw, various years.

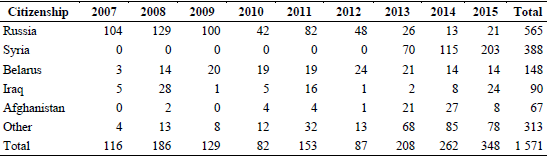

From 1992 through 2009, 3 113 applicants received refugee status (3.5 per cent of all applications). More than half of those approved came from Russia (mostly from Chechnya). Recognised refugees also came from Syria (since 2013), Belarus, Afghanistan and Iraq (see Table 2).

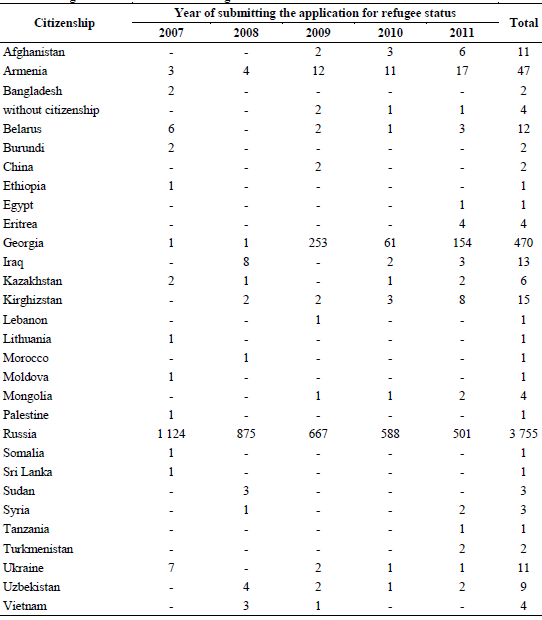

Table 2. The number and nationality of persons granted refugee status in Poland (top five countries) (2007-2015)

Source: Office for Foreigners, Warsaw, various years.

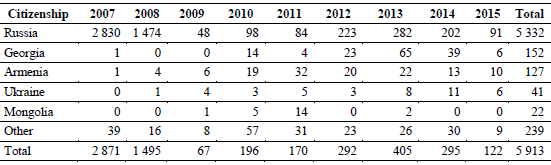

As for other forms of humanitarian protection, the ‘tolerated status’ was granted to 5 913 individuals and ‘subsidiary-protection status’ to 4 348 asylum seekers by the end of 2015 (see Tables 3 and 4). Regarding statistics on ‘tolerated status’ it is worth mentioning that 90 per cent of persons granted a positive decision came from Russia, while 5 per cent were made up of Georgians and Armenians. The same trend is visible in case of ‘subsidiary protection status’. This form of humanitarian protection was given to 93 per cent of applicants from Russia (see Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3. The number and nationality of persons granted 'tolerated status in Poland (top five countries) (2007-2015)

Source: Office for Foreigners, various years.

Table 4. The number and nationality of persons granted subsidiary protection in Poland (top five countries) (2008-2015)

Source: Office for Foreigners, Warsaw, various years.

Legal basis regulating the attendance of refugee and foreign children in Polish schools

It is clear from EU asylum acquis that all asylum-seeking children and refugee children should be granted access to education as foreseen in the Receptions Conditions Directive and the Qualifications Directive.10

The Polish educational system at all levels below the level of higher education is based on the Act of 7 September 1991 on the Educational System (as amended), the Act of 8 January 1999 on the Implementation of the Education System Reform (as amended), and the Act of 26 January 1982 – Teachers’ Charter (as amended). The situation of immigrants’ children in a Polish school is regulated first of all under the Act on the Educational System, in particular in Articles 93.1, 94.1 and 94a.l. Individual issues are addressed in the regulations of the Minister of National Education.

Children who are not Polish citizens can benefit from education and care in public kindergartens and primary schools and junior high schools on the same basis as Polish citizens. The amendment of the Act on the Educational System (adopted by the Parliament on 19 March 2009) extended the access to senior high schools. This solution applies to individuals until they turn 18 years old or graduate from high school. It can therefore be concluded that as a result of this amendment, the universal right to education for individuals until they turn 18 years old, as stipulated in the Constitution (art. 70, item 1 and 2), pertains to foreigners as well.

The access to a specific school is regulated on a territorial basis; i.e. it depends on residence in a given territorial unit. The legal residence status of the child’s parents and/or guardians, including tolerated or unregulated status, is irrelevant here. In the past few years, the rules for accepting foreign children into Polish kindergartens and schools have been simplified. The requirement to recognise school certificates was abolished. Admission to the school is based on the child’s school certificates and/or the total number of schooling years. If this number cannot be proved by documents, a proper grade is established on the basis of statement by a parent, legal guardian or the foreign student himself/herself, provided s/he is an adult. Even when a pupil is unable to provide any documents, s/he can still be admitted to school following an interview. Students with a command of Polish below a level sufficient to benefit from education may be assigned a complementary language course (individual or group classes) of not less than two hours a week. They can also benefit from additional remedial classes in subjects where curricula gaps occur between Polish and foreign schools, as in the case of Polish language lessons, individually or in a group. However, the total number of these complementary lessons, including Polish language, cannot exceed five hours a week per pupil (regulation of the Minister of National Education of 1 April 2010).

An important condition to help the immigrant child’s functioning at a Polish school, provided for in the Act on the Educational System, is the introduction of a cultural assistant to the school. Since 1 January 2010, a child who does not speak Polish sufficiently can benefit from the help of a teaching assistant, employed by the school headmaster – however, up to twelve months only. The Act on the Educational System also regulates the issue of learning the language and culture of the country of origin of a pupil who is subject to compulsory schooling. In consultation with the school headmaster and following the consent of the executing authority, classes devoted to this subject can be organised in schools by diplomatic or consular missions and/or nation-specific cultural and educational associations. The school shall provide rooms and teaching aids for this purpose, free of charge. However, a necessary condition for such classes to take place in a given school is that this school is attended by at least seven immigrant pupils (and in art schools at least fourteen).

Refugee students in Polish schools: main demographic and social features

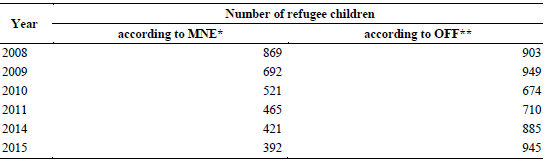

At this point we should examine the overall scale of the phenomenon of immigrants and refugee students in Poland. In September 2015, according to the Education Information System, as many as 2 167 054 students began education in primary schools and 3 189 653 students in high schools. This group included 4 996 students that were not Polish citizens, including 392 refugees. This means that the foreign students accounted for 0.09 per cent of individuals registered in the Polish education system, and the refugee themselves accounted for less than 0.007 per cent of all students. The question remains, however, what share of refugee children the Ministry of National Education’s (MNE) data refer to – statistics from the beginning of the school year do not include short-term stays during the school year. They can also be artificially inflated by students whose families were granted refugee status and then left Poland. The answer can be found in the statistics of the Office for Foreigners (OFF). Let us compare the number of students (including schools and kindergartens) from families applying for refugee status (based on MNE’s statistics) with the number of submitted applications for refugee status for people aged 6–18 (OFF statistics). It turns out that, e.g. in 2009, the Office for Foreigners reported a 5 per cent increase in the number of individuals subject to compulsory education applying for refugee status, whereas MNE’s data reported a decrease of 21 per cent. In 2011 OFF statistics again showed a 5 per cent increase whereas MNE’s data reported a drop of 11 per cent. And again, in 2015 OFF statistics showed a 6 per cent increase whereas MNE’s data reported a decrease of 7 per cent.

Children with refugee status enabling them to stay legally in the Schengen area often ‘disappear’ from the Polish educational system. This phenomenon affects the possibility of achieving educational success when working with a foreign child. This is also reported quite often by the teachers participating in the case-study research findings described in the following parts of this paper. A detailed summary in absolute numbers is offered in Table 5 below.

Table 5. Summary of MNE's and OFF's statistics on the number of refugee children (selected years)

* number of students in September;

** the number of asylum applications filed during the year.

Source: own calculations based on data from the Ministry of National Education and the Office for Foreigners, Warsaw, various years.

The territorial distribution of refugee students is consistent with the logic of establishing refugee centres. The largest group (228 persons in 2011) was registered in schools in the Mazovian Province (central part of Poland). In the same year, 142 students took up education in the Lublin Province and 126 in Podlasie (south-eastern part), while 46 students were registered in Kujawsko-Pomorskie Province (northern part). Other provinces hosted fewer students: there were seven of them in Łódź Province, two in Małopolska, Silesia and Warmia–Mazury, and one in Pomorskie and in Wielkopolskie.

As for refugee students’ countries of origin, the data were provided by the Office for Foreigners and refer to individuals aged 6–18, whose families filed the application for refugee status in a given year (Table 6). Thus it is understandable that the trend observed in this table reflects the patterns in the previously analysed statistics (see Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4). The largest group of students is from Russia, the second group consists of Georgians and the third of Armenians. Citizens of other countries account for 2.7 per cent of registered applications.

Table 6. Refugee students' countries of origin. Poland 2007-2011

Source: Own calculations based on data from the Office for Foreigners, Warsaw, various years.

Individual refugee children have attended Polish schools since the early 1990s but the schools began to admit more groups of children from refugee centres in 2005. At first things were very difficult. Until the introduction of the Regulation by the Minister of Education of 4 October 2001, schoolmasters did not admit children awaiting the decision on refugee status if they could not provide a certificate of their attendance at and/or graduation from a school abroad. Therefore, in 1994–2001, it were mostly children living in the Central Reception Centre for Refugees in Dębak that attended schools since, at that time, it was the only Centre for certified refugees.

As mentioned, access to schools in Poland is regulated on a territorial basis, i.e. registration as a resident of the local community. As a consequence, some schools were ‘overcrowded’ by residents of nearby refugee centres. For teachers it meant an incredible pedagogical effort for which they were usually not prepared. For Chechen children it meant creating ethnic enclaves inside schools, and for Polish pupils it meant receiving far less of the teachers’ attention. There were even cases where Polish parents decided to transfer their children to other schools out of concern for the deteriorating level of education provided to their children. In response to these worrying effects, refugee children started being sent to schools which were not assigned to the area of the refugee centre but were located not too far away from the centre (Gmaj 2007).

Another problem was the discontinuation of education due to a ‘lack of interest on the part of the parents’, as social workers reported. This comment has met with the disapproval of the authors of the report of the Association for Legal Intervention (Kosowicz 2007), who noticed that in relation to the Polish children, ‘parental lack of interest’ is not tantamount to the consent to evade compulsory schooling. In order to change this situation, cash equivalents were offered only to those parents whose children attended schools. As a result, in the 2005/2006 school year more than half of refugee children attended Polish schools, which was still low but, in comparison to the previous years, it was a higher rate. In September 2006 more than 80 per cent of school-aged asylum-seeking children were enrolled in schools (Gmaj 2007). In 2007, 90 per cent of children subject to compulsory schooling were part of the education process (Gmaj 2007; Gmaj and Iglicka 2010). This does not mean, of course, that all the obstacles to providing those students with quality education have been eliminated.

One of the major problems has been and still is the fact that the Polish educational system is not prepared to include students with such specific needs. Schools are not ready in many respects, ranging from a lack of funding and therefore materials that can be used while working in the classroom, to teachers’ expertise and skills in dealing with children that have experienced warfare and exile. And while a number of schools and many teachers demonstrate good will and commitment, there are opposite examples as well. It happens that the school refuses to admit students because it feels unable to cope with the challenge. The situation is gradually improving, inter alia thanks to the enormous commitment of non-governmental organisations that pursue cooperation with schools and local authorities. However, the situation of young people – teenagers who have had a gap in education or have not attended school at all – is still unresolved. The tools and methods to work with such demanding students are lacking. In the case of sixteen- and seventeen year olds, only non-public schools have been able to cope with such individuals so far.

Case study findings

The purpose of the pioneering study on ‘transit’ refugee children in Polish schools11 was to analyse the issue of the inclusion of refugees in the Polish education system as well as children granted international legal protection or waiting to be granted such protection. However, we decided to stress the role of education in the integration process of both children and the whole family. Therefore, the policy-oriented aims of this study were firstly to raise awareness of the importance of education among refugee children, and secondly to argue for the improvement of the skills of teachers and tutors dealing with refugee pupils. This research was conducted in 2013/2014 and financially supported by the European Fund for Refugee and a Polish government grant. Within the scheme of the study, 45 in-depth semi-structured interviews (IDI) were conducted in the three main provinces (15 interviews in each region) where refugee centres have been established: Mazovian Province, the Lublin Province, and Podlasie Province.12 These provinces were selected due to the largest number of refugee centres on their territories. In each province semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives of the Ministry of National Education, school supervisors at national/local levels, school headmasters, teachers, multicultural assistants, refugee pupils’ parents of Chechen origin, NGO representatives and social workers. Seven interview scripts were created depending on the interlocutors. Interviews (recorded and transcribed) were conducted in Polish and/or Russian. Since the interviewers spoke Russian there was no need for interpreters. Apart from the research leader (the author of this paper) and two senior researchers, two local researchers/coordinators were appointed to the project. They were selected from regional universities on the basis of their previous research experience in the field of refugee studies. The research team consisted of demographers, sociologists and anthropologists.

Due to ethical concerns, no refugee children were interviewed. The most important information concerning family life was gathered from the parents.13 In all provinces, 17 interviews with parents and 20 interviews with teachers, school masters and multicultural assistants14 were conducted. Furthermore, three interviews were conducted with social workers15 in each region and five interviews with experts.16

No regional differences were observed in this study as far as integration challenges are concerned, from either the school or local perspective. None of the Chechen respondents (parents) wanted to return to Chechnya, but nor did they perceive Poland as a destination country. Apart from problems with finding a job and making a living they mentioned the lack of an ethnic network to help pave the way for a successful settlement in Poland. This finding supports the observation by Beirens, Hughes, Hek and Spicer (2007) that underlined the important role of refugees’ and asylum seekers’ social networks in providing both the practical and emotional support necessary to mitigate social exclusion and to promote integration within receiving societies.

Social and ethnic divisions between racial and ethnic groups – along economic, cultural, and political lines – are a central feature of public life throughout the world. The problem spans geographical and political boundaries and reflects universal social dynamics. Inequality and conflicts between groups involve not just economic but also cultural and political factors.

The ethnic exclusion may be illustrated in our case with a casus of one of Chechen girls in our study who could not make friends either with the Chechens – as for them, she was a Pole since she spoke Polish without an accent – or with the Poles, as these in turn perceived her as a Chechen. The teacher advised her not to wear a long traditional skirt, but it did not help; once she moved to another school problems ceased to exist, but only until two other Chechen girls joined the class.

According to interviewees – specifically, Polish teachers and Chechens professionally involved in supporting the educational process – students from Chechnya show higher levels of aggression compared to Polish students. It was not possible to obtain any systematically collected data to confirm this finding. Perhaps it is a construct based on cultural diversity, perhaps due to the different motor reactions and facial expressions, explicitly manifested also outside of school? However, we cannot disregard completely the problem of violence in schools reported by school representatives. Here is how the situation is presented by a tutor (of Chechen origin) of a ‘Chechen reception class’:

Depression, aggression, it’s in this kid all the time – wants to fight in class – I must separate them, tell that they don’t have to fight, that we don’t beat each other in Poland, but we – the teachers – we can’t beat them or even raise our voice, and this child who is used to being beaten, doesn’t listen to us... doesn’t want to talk. He is used to being beaten, but he doesn’t want to talk – kids make trouble all the time. We teach them all year round not to fight, not to touch each other, ‘you can’t’, ‘you mustn’t’ – all the time we have to take care of discipline and order... (NAU2POD).

As this same tutor notes, aggression occurs as a consequence of traumatic war experiences:

They shouldn’t be aggressive, and here, we have both anger and aggression – it came from their parents – either from the family or they have it inscribed in their genes – I don’t know, I’m terrified; I worked at the school until the war broke out [in Chechnya], and never have I seen such an aggression. (...) The first year when I came to this class, I shook my head in disbelief – so, how can you behave like that? I haven’t seen such children (...) they do want a fairy tale ... but do you know what they kind of a fairy tale they want? Not the usual one, they want to play only with weapons. And fairy tales – they want it to be a fairy tale with knives, fights, they want the protagonists to die – that’s the only fairy tale they want. ‘Why you don’t have such fairy tales here?’ – they asked me yesterday. Reception class, kids 5 and 6 years old, and they want fairy tales with murders… (NAU2POD).

Such statements as ‘they have violence inscribed in their genes’ shows that the teacher is completely unprepared to deal with children who are possibly suffering from a post-traumatic syndrome, however. Since these words came from a tutor of Chechen origin, it is worth remembering that simple tutor selection ‘by ethnicity’ does not necessarily mean having the appropriate skills to deal with foreign children with special needs.

The ethnic exclusion is also related to economic exclusion (Łodziński 2009). As Algan, Dustmann, Glitz and Manning (2010: 40) observe: ‘there are a number of reasons why the integration of immigrants and their children matters. The more successful immigrants are in the labour market, the higher will be their net economic and fiscal contribution to the host economy. On the other hand, poor economic success may lead to the social and economic exclusion of immigrants and their descendants, which in turn may lead to social unrest, with riots and terrorism as extreme manifestations’.

As was indicated by one of the female workers of NGOs, coming from Chechnya: in these families there is shortage, instability, uncertainty... experienced by the children (NGO1POD). The respondents all emphasise the difficult financial and housing conditions of the Chechen families.

Some of them live in hotels and not in the centre, or at least they say so, because these are the cellars nearby the hotels that someone let to them (NGO1POD). Housing problems are primarily due to very high rents, exceeding several times the standard rates on the market. This issue has also been raised in other studies (Kasprzak and Walczak 2009). High prices and frequent cases of terminating the tenancy agreement after a short period translate into repeated address changes for the child and, consequently, into troublesome commuting or a transfer to another school. Functioning under conditions of economic deprivation strongly affects a child’s educational career (Warzywoda-Kruszyńska 2009). As one of the teachers notes:

Shortage, poverty in the family, they don’t bring sandwiches, don’t eat at school (...) all are depressed (...) who rents the apartment, it’s this depressed family, because they can’t afford to buy clothes and their kid feels humiliated (PS3LUB).

The social workers themselves do notice this issue.

They definitely do not show us all the money they have, they surely receive these funds from abroad, since just with our money they wouldn’t survive for sure. They benefit from EU funds, i.e. food from EU funds as well, so, we are trying to support them. (...) There are different organisations present and involved. Is it enough for them? Certainly not – let’s face it, certainly not. Speaking of today, there were and there still are some difficulties in finding employment (PS4LUB).

The difficulty of finding a job and making a living in Poland results in a situation where Poland tends to be perceived as a transit country. According to all respondents, who due to their professional obligations deal with persons seeking international legal protection in Poland, it translates into the outflow of refugee students from the Polish educational system:

We used to have a girl named H., who won a competition, the dictation in Polish language, she defeated all Poles; and there was math – she was a math genius (...) there were no barriers for H., either linguistically or scientifically (...), a simply exceptional, unique girl... She was with us for two years and then went away, because here, they did not have the means to live (DYRPOD2).

Another dimension of temporariness translates into an ‘artificial’ presence of some Chechen children at schools:

They come to school but quite often do not attend classes, they just circulate in the corridors. They know that the real school will be in Germany, here it is for a few months only so it makes no sense to attend (DYRPOD2).

A serious issue is the maladjustment of cultural gender roles in the receiving society.

In the Chechen group, there are a lot of families without a father. In such a case, teenage sons take over the role of the head of the family, and then the influence of mothers definitely weakens. The oldest boy in the family quite often simply does not know how to deal with the tasks they face, and they often ‘go off the rails’, fleeing from responsibility (DYR4MAZ).

The position of a husband and father in the family, conditioned and formulated culturally, may be an impediment to the educational career of a student. Children develop at school, and females tend to integrate more quickly than males, thereby undermining the place of the male in the family hierarchy. This may even lead to conflict within the family, especially when the male fails to support his family. It therefore happens that children do not lack motivation, but that they are literally held back by their parents. Consequently, there are cases where Polish teachers cannot count on the support of some adults, even if the language barrier disappears. In addition to the situations referred to above, some shifts in the division of gender roles in the family were observed. A traditional patriarchal family is confronted with an egalitarian division of labour in the world around. Such a difficult situation can easily be stereotyped by local people.

They were coming here, to Poland, and women, at some point, took over the role of men and started to work, the men sat in the house – they started to like it, practically. In the past they were shooting and fighting, now they simply sit holding a remote control. These are different situations, they don’t want to go out so, I think, at some point they... well, they started to be quite well, so why not? A woman can putty, paint, bring home some things and earn money while a man can sit and relax (PS1POD).

A different perspective is provided by Chechen parents. Families living in poverty have fallen into stagnation and frustration.

The time is over, when, let’s say, these documents are in place, right? You feel as if you have done everything you could (...) the state of a kind of passiveness, you don’t know what to do, job’s not right, and this lack of motivation to get up and go outside (RODZ3MAZ).

A fairly evident problem is the inadequacy of financial aid, compared to families’ needs. MOPR (local/municipal family support centre) offers as a kind of ‘sure start’ a benefit of PLN 500 per person, which is (as of mid-2016) equivalent to about EUR 120.

And what can he do with these PLN 500? He won’t go stealing, and you have to pay the apartment, electricity, shoes, shampoo, conditioner. (...) And what can he do with these PLN 500? (RODZ5POD).

As mentioned, none of the Chechen respondents (parents) viewed Poland as a destination country. One of the important factors behind such perception is the lack of an ethnic network in Poland.

We have a family in Germany, they have a car there and a small house. We want to be with them. Would be much easier there (RODZ3MAZ).

And they have grandfathers there… (RODZ2POD).

As the contact between cultures continues to increase, its impact on cultural identity and belonging is unclear, especially in the context of ethnic groups’ formation. As Barth (1998: 11) notices: ‘The difference between cultures, and their historic boundaries and connections, have been given much attention; the constitution of ethnic groups, and the nature of the boundaries between them, have not been correspondingly investigated. Social anthropologists have largely avoided these problems by using a highly abstracted concept of “society” to represent the encompassing social system within which smaller, concrete groups and units may be analysed. But this leaves untouched the empirical characteristics and boundaries of ethnic groups’.

For them [local people], it’s maybe nothing special, but for us and for the child, it is – new neighbours in the staircase, new environment, it is all new. (...) And we wonder again, how will they welcome us, accept, maybe we won’t even be able to pass through this staircase. (...) It may happen, too (RODZ1POD).

Chechen parents’ approach to their children’s education is influenced by many factors, such as the transition to a utilitarian model of education, interim status, economic deprivation, and last but not least: the educational model of the patriarchal family, which is disadvantageous for women. Some elements of gender scripts remain unchanged, as evidenced by two statements made by a Chechen married couple. Woman: I attend every single [meeting], I take care of children, man: I attend too – I was there once. You’ve got to (RODZ1,2MAZ).

She is already fourteen. She could have two children and a husband. Why must she be in school here? (RODZ4POD).

Uncertainty, temporality – the result of lengthy procedures, ethnic and economic exclusion – will obviously have an impact on the development of the student’s educational career. According to the case study findings it has also an impact on the teacher: it is harsh to invest in and be devoted to a student who spends just a few months in the classroom.

Conclusions

This article describes a range of complex problems and phenomena that should be considered from at least three perspectives. Firstly, they should be considered from the Polish perspective; secondly, from the perspective of migratory movements in the EU; and finally, from the perspective of East–West mobility in the global context of the current refugee crisis and global and regional disparities.

In the past twenty years, almost 90 000 Chechen refugees have come to Poland, as it was the first safe country they reached. There were a few factors that played an important role in the ‘welcoming attitude’ by Poles. Firstly, the Poles’ mostly negative attitude towards Russia and their objection to Putin’s aggressive policies towards the newly established countries of the former USSR made them naturally sympathetic. Poland’s own experiences with the USSR could easily ignite Polish solidarity not only with Chechnya, but also with Georgia and Ukraine. Secondly, Poland has been taking asylum seekers from Chechnya not only for reasons of solidarity but also with the intention of fully complying with European Union law, specifically the Dublin III Regulation17 (Stummer 2016).

The results of the study suggest that Polish immigration policy had no impact on the choice of destination of the refugees interviewed. None of the interviewees wanted to return to Chechnya, but nor did they view Poland as a destination country. The existence of family links in Western Europe, or a general sense of Western Europe and its welfare system as a ‘good place’ to develop one’s life, rather than specific policy measures appear to be the main reason for the majority of refugees to see Poland as a transit country. ‘The majority of them are not planning to settle down there at all. Poland is for them a transit state on their way to Western European countries like Germany, France, or Belgium’ (Stummer 2016).

This phenomenon is mirrored in educational statistics and in the phenomenon of vanishing Chechen pupils form the Polish schools. It should also be stressed here that Chechens’ model of the patriarchal family is extremely unfriendly towards education, especially in the case of girls.

Although the size and selectivity of the participant group in the study described above limits generalisations, this exploration does provide some insight into nodal decision-making points in the Chechens’ migration process: escaping hell (Russia), being in purgatory (Poland), in order to find paradise (Western Europe). The picture has less to do with immigration policies and their implementation and more with the lack of ethnic networks and economic opportunities in Poland. The attitudes and needs of Chechen refugees concerning the destination area should therefore be taken into consideration, especially by politicians trying to implement a common immigration policy in the EU countries, irrespective of still huge regional economic and development disparities.

The above conclusions do not detract from or undermine the immense efforts by Polish institutions, and schools especially (as shown in the study), to integrate and help Chechen refugees.

Notes

1 The study was conducted in the school year 2013/2014.

2 http://cbu.psychologia.pl/uploads/aktualnosci/%C5%81OM%C5%BBA%20RAPORT%202012.pdf, http://ffrs.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/FRS_Badania_Rekomendacje_2014.pdf, http://ffrs.org.pl/pl/?s=kubin+pogorzala (accessed: 9 June 2017).

3 http://www.csm.org.pl/en/completed-projects/94-i-kids (accessed: 9 June 2017).

4 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32004L0083:en:HTML (accessed: 9 June 2017).

5 Since October 2015, the Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy.

6 Law of 18 March 2008 changing the Act on the Protection of Foreign Citizens, Journal of Laws 2008, No. 70, item 416.

7 http://www.bip.msw.gov.pl/portal/bip/227/19529/Polityka_migracyjna_Polski.html (accessed: 4 November 2016).

8 http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/diminishing-solidarity-polish-att... (accessed: June 2017).

9 http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/diminishing-solidarity-polish-att... (accessed: June 2017).

10 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32013L0033, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32004L0083:en:HTML (accessed: 9 June 2017).

11 http://www.csm.org.pl/en/completed-projects/94-i-kids (accessed: 9 June 2017).

12 Designated as MAZ, LUB and POD, respectively.

13 Designated as RODZ.

14 Designated as NAU, DYR and NGO, respectively.

15 Designated as SW.

16 Designated as EXP.

17 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:180:0031:0059:EN:PDF (accessed: 9 June 2017). According to the regulation, every asylum seeker who crosses the border of the EU needs to register him or herself in the first EU country where he or she entered the European Union. For Chechens that usually means Poland.

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

Algan Y., Dustmann C., Glitz A., Manning A. (2010). The Economic Situation of First and Second-Generation Immigrants in France, Germany and the United Kingdom. The Economic Journal 120(542): 4–30.

Barth F. (1998). Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organisation of Culture Difference. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Beirens H., Hughes N., Hek R., Spicer N. (2007). Preventing Social Exclusion of Refugee and Asylum Seeking Children: Building New Networks. Social Policy and Society 6(2): 219–229.

Bieniecki M., Kaźmierkiewicz P., Smoter B. (2006). Integracja cudzoziemców w Polsce. Wybrane aspekty. Warsaw: Institute of Public Affairs.

Black R. (2001). Fifty Years of Refugee Studies: From Theory to Policy. International Migration Review 35(1): 55–78.

Chrzanowska A., Gracz K. (2007). Uchodźcy w Polsce. Kulturowo-prawne bariery w procesie adaptacji. Warsaw: Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej.

Common Basic Principles for Immigrant Integration Policy (2004). Online: http://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/common-basic-principles_en.pdf (accessed: 15 July 2016).

Czerniejewska I. (2013). Edukacja wielokulturowa. Działania podejmowane w Polsce. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UMK.

Dryden-Peterson (2015). The Educational Experiences of Refugee Children in Countries of First Asylum. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

European Commission Library and e-Resources Centre (2015). Selected Publications on Refugees’ and Migrants’ Integration in Schools. Online: http://ec.europa.eu/libraries/doc/refugees_and_migrants_integration_in_s... (accessed: 9 June 2017).

Głowacka-Grajper M. (2006). Dobry gość. Stosunek nauczycieli szkół podstawowych do dzieci romskich i wietnamskich. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Prolog.

Gmaj K. (2007). Educational Challenges Posed by Migration to Poland. Online: http://www.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/en/2008/10/education_poland_fin... (accessed: 5 November 2016).

Gmaj K., Iglicka K. (2010). Wyzwania związane z imigracją do Polski. Wymiar edukacyjny, rynku pracy i aktywności politycznej dotyczący obywateli państw spoza Unii Europejskiej, in: K. Iglicka, M. R. Przystolik (eds), Ziemia obiecana czy przystanek w drodze?, pp. 170–191. Warsaw: Biuro Rzecznika Praw Obywatelskich.

Halik T., Nowicka E., Połeć W. (2006). Dziecko wietnamskie w polskiej szkole. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Prolog.

Iglicka K. (2001). Poland’s Post-War Dynamic of Migration. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Iglicka K. (2002). ‘Poland: Between Geopolitical Shifts and Emerging Migratory Paterrns’, International Journal of Population Geography, no 8: pp. 153–164.

Iglicka K. (2010). Migration Research in a Transformation Country: The Polish Case, in: D. Tranhardt, M. Bommes (eds), National Paradigms of Migration Research, pp. 259–266. Osnabrück: V & R unipress, Universitätsverlag Osnabrück.

Iglicka K. (2014). Poland – A Country of Enduring Emigration, in: F. Medved (ed.), Proliferation of Migration Transition. Selected New EU Member States, pp. 84–115. European Liberal Forum. Online: file:///C:/Users/rs/Downloads/Proliferation%20of%20Migration%20Transition.pdf (accessed: 9 June 2017).

Iglicka K., Gmaj K. (2015). Od integracji do partycypacji. Wyzwania imigracji w Polsce i Europie. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Iglicka K., Ziolek-Skrzypczak M. (2010). EU Membership Highlights Poland’s Migration Challenges. Online: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/eu-membership-highlights-polands-... (accessed: 12 June 2017).

Januszewska E. (2010). Dziecko czeczeńskie w Polsce. Między traumą wojenną a doświadczeniem uchodźstwa. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek.

Kasprzak T., Walczak B. (2009). Diagnoza postaw młodzieży województwa podlaskiego wobec odmienności kulturowej. Raport z badania, in: A. Jasińska-Kania, K. M. Staszyńska (eds), Diagnoza postaw młodzieży województwa podlaskiego wobec odmienności kulturowej, pp. 51–196. Białystok: Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Podlaskiego.

Konieczna J., Świdrowska E. (2008). Młodzież, imigranci, tolerancja. Raport z badań terenowych w szkołach. Warsaw: Institute of Public Affairs.

Kosowicz A. ( 2007). Access to Quality Education By Asylum-Seeking and Refugee Children. Poland Country Report. Warsaw: UNHCR.

Łodziński S. (2009). Uchodźcy w Polsce. Mechanizmy wykluczenia etnicznego, in: A. Jasińska-Kania, S. Łodziński (eds), Obszary i formy wykluczenia etnicznego w Polsce. Mniejszości narodowe, imigranci, uchodźcy, pp. 181–203. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Łodziński S., Ząbek M. (2010). Perspektywy integracji uchodźców w społeczeństwie polskim. Wyzwania normalnego życia, in: K. Iglicka, M. R. Przystolik (eds), Ziemia obiecana czy przystanek w drodze?, pp. 224–256. Warsaw: Biuro Rzecznika Praw Obywatelskich.

MI (Ministry of the Interior). Migration Policy of Poland – the Current State of Play and Further Actions. Warsaw: Ministry of the Interior.

Siarkiewicz A. (2001). Status uchodźcy i co dalej? Z obcej ziemi 13: 20–31.

Stummer K. (2016). Forgotten Refugees: Chechen Asylum Seekers in Poland. Online: http://politicalcritique.org/cee/poland/2016/forgotten-refugees-chechen-... (accessed: 2 November 2016).

Szelewa D. (2010). Integracja a polityka edukacyjna. Warsaw: Center for International Relations.

Warzywoda-Kruszyńska W. (2009). Dorastać w biedzie – obrazy z życia różnych pokoleń łodzian, in: W. Warzywoda-Kruszyńska (ed.), (Żyć) Na marginesie wielkiego miasta, pp. 67–81. Łódź: Wydawnictwo „Absolwent”.

Ząbek M., Łodziński S. (2008). Uchodźcy w Polsce. Próba spojrzenia antropologicznego. Warsaw: Polska Akcja Humanitarna.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.