Nationality and Rationality: Ancestors, ‘Diaspora’ and the Impact of Ethnic Policy in the Country of Emigration on Ethnic Return Migration from Western Ukraine to the Czech Republic

-

Author(s):Jirka, LuděkPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2019, pp. 117-134DOI: 10.17467/ceemr.2019.01Received:

31 March 2018

Accepted:21 May 2019

Published:29 May 2019

Views: 12178

Ethnic return migration is a widespread strategy for migrants from economically disadvantaged countries. This article is about those ethnic return migrants who might successfully migrate thanks to their ancestors; their decision is based upon economic, pragmatic or rationalistic incentives aside from their diasporic feeling of belonging. Although this phenomenon has already been studied, scholars still mostly refer only to the benefits proposed by immigration policy as a key to understanding it. The impact of policy in the country of emigration on ethnic return migration is understudied. This article fills this gap. I found that when the Soviet Union introduced an attractive policy for Ukrainians/Russians in terms of study or work opportunities and the inhabitants in the Ukrainian Soviet Republic were quick to proclaim themselves as Ukrainians or Russians, the dissolution of the Soviet Union quickly changed this motivation. Ukrainians with Czech ancestors started to aim at obtaining official status as Czech members of the diaspora because of the benefits proposed by the Czech government (mainly permanent residency). However, it is difficult to prove the required link to one’s Czech ancestors due to Soviet-era documents in which the column with the Czech nationality of people’s ancestors is often missing. These observations lead to the conclusion that an attractive immigration policy aimed at the diaspora should not be treated as the only comprehensive explanation for ethnic return migration. Ethnic policy in the country of emigration also shapes this kind of migration and – in this concrete case – could even discourage ethnic return migrants.

Introduction

The father was Kazakh and the mother Czech, or conversely, and the child is registered as Kazakh. The child is living in Kazakhstan and wants to go further, further and further. [In Kazakhstan] he wasn’t able to do anything, there are no opportunities, so he thinks: ‘Ok, I will move to my mother’s home country – there is the advantage of migrating somewhere else’ [because of maternal heredity]. Do you understand? [They are doing it] right this way (N. G., Dubno, Ukraine, 5 April 2012).

Migration to the European Union is highly promoted today in the media; however, the publicity is mainly dedicated to situations on the southern borders of the European Union, where refugees struggle to stay alive. The publicity given to East-to-West migration is now minor compared to its South-to-North direction, although the former migration stream remains important. Unsuccessful transitions to democracy and market economies after 1991 triggered migration from Eastern Europe to Central and Western Europe (Castles and Miller 2003). Migrants from Russia, Moldova, Ukraine and Belarus moved to Central European countries such as Poland, Germany or the Czech Republic, as well as to Southern European countries such as Spain, Italy or Portugal (Fedyuk and Kindler 2016; Markov 2009; Libanova and Poznjak 2010).

Migration from Ukraine has different meanings over time according to the political and economic situation in the country. Mobility outside Ukraine is now strategic and even Ukrainians who did not decide to migrate before 2013 are now tempted to move. Critical is combination of the Euromaidan, the war in Eastern Ukraine and following economic regression. The most popular countries are now Poland and Russia (Jaroszewicz 2015). Mobility to the European Union has also recently become a strategy for those from central and eastern parts of Ukraine, not just for Ukrainians from its western part (Jaroszewicz and Piechal 2016).

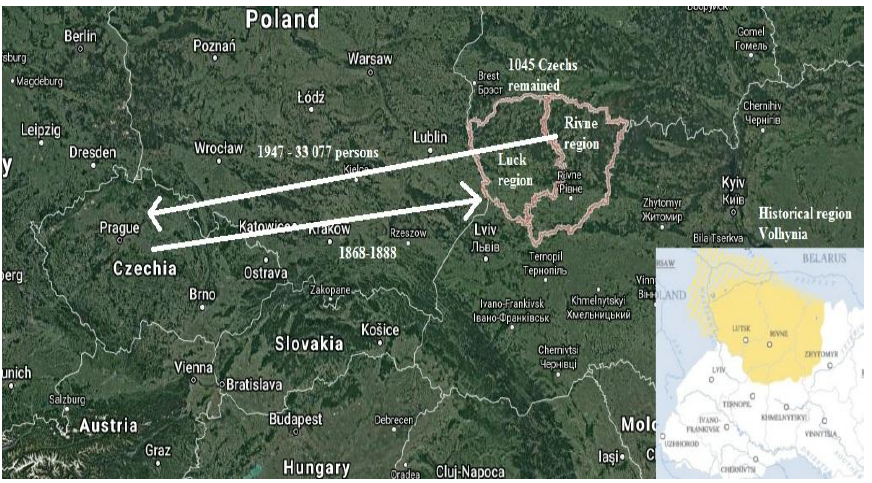

This paper is devoted to migrants from West Ukraine who have Czech ancestors. Many of these migrants – recent members of the Czech diaspora in West Ukraine – are the descendants of Czech immigrants from the second half of the nineteenth century (approximately 1868–1888). There were almost 40 000 Czechs in Western Ukraine during the interwar period – when it was part of Poland – but most of them repatriated to Czechoslovakia in 1947 after the war when West Ukraine became part of the Soviet Union. Some did not receive permission to repatriate in 1947, others were imprisoned in Soviet labour camps (gulags) and still others simply did not want to repatriate for personal or family reasons. There were also those who had unexpected deaths or serious illnesses in the family or problems with personal documents. Other specific constraints were mixed marriages – women whose husbands were of non-Czech origin were not allowed to repatriate, while men married to wives with non-Czech origins were allowed to. According to repatriation documents, 34 122 persons wanted to repatriate in 1947 (Vizitiv 2008), 34 010 persons received approval and only 33 077 of them actually repatriated.1 In all, 933 persons did not move to Czechoslovakia in spite of their approval for repatriation, while a further 112 persons were not given permission. In total, 1 045 Czechs failed to repatriate, although the number of non-repatriated Czechs is actually higher, for political and social reasons. Many of these non-repatriated Czechs remained sparsely distributed among Ukrainians after 1947 so that mixed marriages occurred.

Ukraine is an independent state today, but the Soviet Union’s heritage is still prominently important, at least for ethnic return migrants. I argue that Russian (as the leading nation in Soviet Union) and Ukrainian nationality (as a leading nation in the Ukrainian SSR) was preferred in Soviet era because of the greater possibilities to access an education and a career. These nationalities were also preferred because they aroused less suspicion with the Soviet security agency (KGB; Committee for State Security). Consequently, Czechs living in the Ukrainian SSR often claimed Russian and Ukrainian nationality and therefore it was a rationalistic decision which sometimes went against their ‘true’ ethnic consciousness. However, the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 changed all this and suddenly Czech nationality became more attractive because of the unsuccessful Ukrainian transition to a market economy, the economic crisis in Russia, and the growing tendency for emigration from West Ukraine to Europe. Ukrainians with Czech ancestry today proclaim themselves as members of the Czech diaspora because of the benefits – such as permanent residency in the Czech Republic – offered to them by Czech government. However, to achieve confirmation of their belonging to the Czech diasporic community abroad and then permanent residency, it is necessary to prove the linkage to their Czech ancestors with documents recording Czech nationality.

I show in this paper that young and middle generations of Ukrainians with Czech ancestors refer today to their Czech descent and derive benefits from membership in Czech diaspora, but ‘blank space’ from Soviet era is a big constraint. However, they have rationalistic rather than nostalgic incentives to ‘return home’ and their pragmatic decision is driven by the harmful economic and political situation in Ukraine. This type of migration fits into the concepts of ‘ethnic return migration’ (Tsuda 2003, 2009) or ‘ethnomigration’ (Brubaker 1998). Scholars researching this type of migration, aside from studying the pragmatic decisions of migrants, focus mainly on the ‘diaspora’ policy in the country of immigration as a crucial aspect which encourages ethnic return migration. Indeed, ‘diaspora’ members are attracted by the scale of the different kinds of benefits promoted by the country of immigration, like being able to obtain a house or finances (Anghel 2013). They are often privileged as members of the nation (Joppke 2005). Pull factors in terms of policy towards the ‘diaspora’ in the country of immigration are very important and this is the case in the Czech Republic. However, in this paper, I ask a question: Does policy in the country of emigration also have any influence on ethnic return migrants? It may be taken as a matter of course, but which conditions are there concretely? To understand that point, I refer to the Rivne and Volyn regions (West Ukraine) as emigration areas and the Czech Republic as an immigration country. Consequently, I claim that both Soviet and Ukrainian ethnic policies played their role in shaping the contemporary ethnic return migration from Ukraine to the Czech Republic, but the Soviet one was even more influential.

The first section of this paper is dedicated to the theoretical implications of my research and the second is about the methodology – i.e. my anthropological fieldwork in the Rivne and Volyn regions in West Ukraine. The third section concerns Soviet ethnic policy and ethnos theory while the following sections deal with proclaimed nationalities in the Soviet era and independent Ukraine, Czech policy towards the ‘diaspora’, participants and their nationality and the national identity declared in documents. To conclude, I show how Czech members of the ‘diaspora’ in post-Soviet Ukraine and, more generally, ethnic minorities in post-Soviet countries, present their nationality, how they are treated and defined and how the flow of ethnic return migration is limited. This paper does not cover the emigration policy of the Soviet Union or post-Soviet Ukraine, but only the interior policy of the two regimes and its impact on ethnic return migration. In this article the term nationality refers to ‘membership of a national minority living within a state and/or culturally linked to an external national “homeland”’ (Bauböck, Ersbøll, Groenendijk and Waldrauch 2006: 485) as it is often used in Central and Eastern Europe (Brubaker 2006).

Theoretical implications

Ethnic return migration could be interpreted as (a) migration driven by diasporic attachment, nostalgia, or ethnic ties to homeland (e.g. Cohen 1997; Safran 1991; Tsuda 2009) or as (b) migration of later-generation diasporic descendants who are fully assimilated in their countries of birth and who lose their ‘ancestral’ culture to a considerable extent (Tsuda 2009). In this article, I deal with the latter approach to ethnic return migration, because the studied ethnic return migrants are strongly embedded in structural, social and cultural norms – i.e. they fully identify with the majority in their country of birth, due to their intra-generational assimilation into the local environment (through intermarriage, urbanisation and linguistic and cultural assimilation2 and they express the ethnic subjective consciousness of the majority.

Nevertheless, ethnic ancestors can be ‘used’ even if ethnic return migrants do not express any ethnic closeness to the nation of immigration but respond to merely economic incentives (economic prosperity, living conditions, a developed labour market – Fox 2007; Kulu and Tammaru 2000; Tsuda 2003, 2009; Waterbury 2006). They could even be seen as ‘labour migrants’ (Fox 2003, 2007; Skrentny et al. 2007; Tsuda 2009; Waterbury 2006, 2014). The situation could also be interpreted as a deception of official policy (Iglicka 2001; Tsuda 2009).

Generally speaking, scholars deal mainly with the political level in the case of ethnic return migration – i.e. they analyse the policy of the country of immigration as being favourable towards ‘members of diaspora’ and as forming immigration flows (Fox 2003, 2007; Iglicka 2001; Joppke 2005; Joppke and Rosenhek 2009; Kulu and Tammaru 2000; Tsuda 2009; Skrentny et al. 2007; Waterbury 2014).3 Immigration is then explained by the attractive policy of economically advanced countries, which channeled migration (Tsuda 2009) by offering benefits (i.e. citizenship, better jobs or pensions, entrance into fully developed welfare systems, etc.). As Christian Joppke and Zeev Rosenhek (2009) explicitly put it, countries of immigration produce ethnic return migration.4 In reality, countries set preferential policy for various reasons. Nevertheless, some scholars have dealt with the immigration policy of specific countries as the sole cause of the rise and fall of ethnic return migration (Iglicka 2001; Joppke 2005; Skrentny et al. 2007; Waterbury 2006, 2014). Following such reasoning, one could claim that, if countries of immigration stopped their preferential immigration policy towards members of the diaspora, ethnic return migration would become insignificant (and vice versa). Other explanations for fluctuations in ethnic return migration – such as social networks and information flows, the proximity of language (Fox 2007; Kulu and Tammaru 2000) or education for children (Kulu and Tammaru 2000)5 – remain smaller in scale; however, these social networks are very often not present (Brubaker 1998; Kulu and Tammaru 2000; Tsuda 2009).6

Conditions in the country of birth are often described as impoverished (Fox 2007; Joppke and Rosenhek 2009) and this affects ethnic return migration. Indeed, the return migration of Russian Jews, ethnic Germans from the Soviet Union / Russia, ethnic Koreans from China or ethnic Japanese from Brazil is explained as the consequence of economic crises in their countries of birth (Tsuda 2009). Another explanation is ethnic persecution (Joppke 2005; Kulu 2002; Tsuda 2009) or environmental change (Kulu 1998). Economic regression is, however, seen as the primary reason for leaving. In this sense, ethnic return migration is a product of global disparities of wealth. At the same time, almost no effort has been made to properly describe policies in the country of emigration and how they shape the decisions of ethnic return migrants.

In other words, in the literature, the political impacts of countries of emigration on ethnic return migrants are often neglected, although they could potentially cause or hinder migration. In this article, I try to fill this gap, by showing that immigration policy is not the only politically based element ‘producing’ ethnic return migration and that policy in the country of emigration could also crucially impact on it. I present policies from the Soviet Union and independent Ukraine to shed more light on this issue. This leads me to ask how policy in a migrant’s country of birth, accompanied by policy in the country of immigration, influences ethnic return migration.7

Methodology

Qualitative research was conducted with members of Czech diasporic associations from the Rivne and Volyn regions in West Ukraine (see Map 1) (the Czech association Stromovka, in Dubno, the Association of Czech Matice Volynska in Luck and the Czech association in Rivne) during the years 2012–2015. These Czech diasporic associations are relatively small and consist not only of members of the ‘diaspora’ but also of the spouses and relatives of members of the ‘diaspora’ and their sympathisers. The Association of Czech Matice Volynska in Luck had 220 members in 2013; however only 70 members remained after its reorganisation in 2014. The Czech association Stromovka in Dubno had 264 members in 2013 and the association in Rivne had 72 members in the same year.

Map 1. Migration flows of Czechs between Czechia and Luck region and Rivne region

Source: googlemaps.com, pysanky.info.

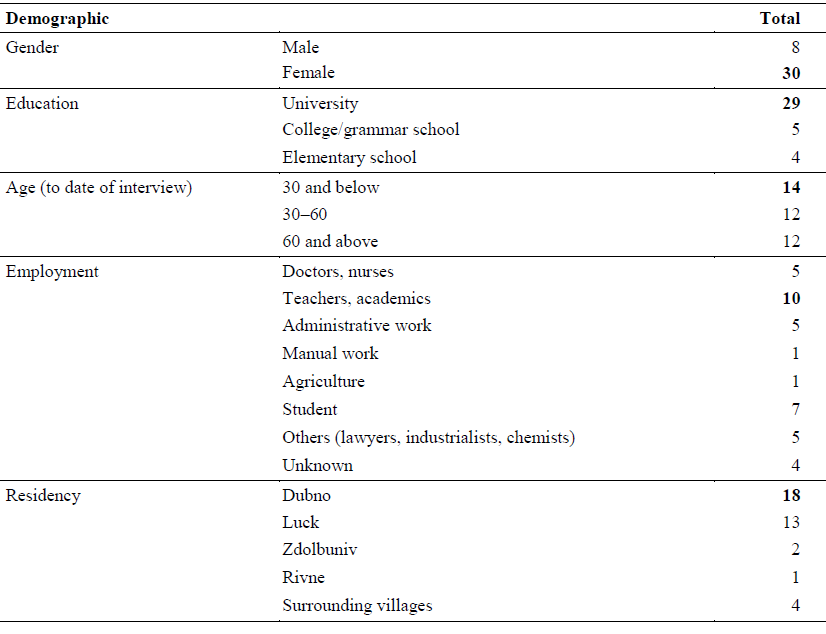

Semi-structured interviews were held in Czech diasporic associations. Twenty-eight interviews were conducted with members of the ‘diaspora’ (those with Czech ancestors) and ten with other association members. Five of the latter were convinced that they had Czech ancestors, but were unable to prove it by documents. Another five participants were without Czech ancestors. However, all were connected with Czech diasporic associations. It was not always possible to interview a whole family each time for different reasons (some refused to be interviewed, older-generation participants refused to be recorded, and some were abroad at the time). Complete families were interviewed only in four cases, and family members were mostly in a ‘mother–child’ (older–middle generation) relationship.

Table 1. Demographic information about participants

To this day, older-generation of Czech diaspora (60+ years old) have one or two Czech parents, the middle generation (30–60 years old) have one Czech parent or one grandparent, and the younger participants (up to 30 years old) often have only one Czech grandparent or just one great-grandparent.8 Participants from the older generation expressed their Czech ethnic consciousness but have no intention of migrating. Middle-aged participants expressed their Czech as well as Ukrainian ethnic consciousness (depending on their childhood and personal development), while the younger generation expressed Ukrainian ethnic consciousness. Members of the young and middle generations are mostly affected by emigration tendencies; the decision to migrate by those of the younger generation is mostly a pragmatic one for the purpose of study (fee-free) or work, and still enroll as members of the Czech diaspora. Most had made tourist trips to the Czech Republic – a country which they consider to be economically and materially advanced compared to Ukraine. On the other hand, their attitude towards the Ukrainian state and society is negative – they consider Ukrainians as passive and xenophobic, and Ukraine as a bad state in which to live. These are crucial factors encouraging them to enroll as members of Czech diaspora, as one participant, I. K., from Dubno in Ukraine stated in an interview on 9 July 2013:

I. K.: In the Czech Republic life is more interesting. You don’t know what to do in Ukraine on the weekend. There is nowhere you can go.

L. J.: I know what you are talking about.

I. K.: People in the Czech Republic have swimming pools and other activities. It is also in Ukraine, but not as in the Czech Republic.

Firstly, I contacted participants from the older generation who are active leaders in Czech diasporic associations; they in turn put me in touch with their family members. Participants from the younger generation were the last to be interviewed because I presumed that the most relevant information which would clarify the situation in the Soviet Union and after the independence of Ukraine in 1991 could be gained from interviews with the older generation. However, the younger generation was important when researching their migration intentions.

This research was launched in Dubno, a small town in the Rivne region and the centre of the Czech diaspora before 1947. In Dubno the most active Czech diasporic association – Stromovka – was also located. Participants also came from the surrounding villages and from the towns of Luck, Zdolbuniv and Rivne. The average interview lasted about 90 minutes. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and saved in my personal archive.

At the beginning of the interview, participants were asked to recount their life story; any additional questions were then asked. In the interviews, participants emphasised their relationship with their Czech ancestors and the Czech nation, culture and folklore. My positionality as being of Czech ethnicity was crucial, as participants often felt able to proclaim their closeness to the Czech nationality and they talked mainly about others when they wanted to emphasise how they dealt with the problem of nationality. Participants were more open about themselves after further appointments with me, although they often were not entirely frank with me and I had to tease out certain details or contexts in the participant’s life course during ‘little chats’ with them (or with others). Additional questions concerned the ethnicity of the participants and of their ancestors and any documentation proving the latter relationship, ethnic policy and nationality issues in the Soviet Union and independent Ukraine and the process of proving their belonging to the Czech diasporic community abroad and gaining permanent residency in the Czech Republic.

An interview was also obtained with Miroslav Klíma, the General Consul of the Czech Republic in Lviv. Notes from my field diary served as clarification together with my ‘little chats’ with non-interviewed members of Czech associations and other inhabitants in West Ukraine (written also into field diary).

Soviet Union policy: ‘Be a member’ of a nation

It is necessary to understand the historical background – in this case the Soviet regime in West Ukraine – and its implications for the current situation. During the Soviet regime the interrelatedness of nation and specific territory had a strong effect (Skalník and Krjukov 1990). This involved the territory of the Soviet Republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, Kazakhstan, Kirghizia, Moldavia, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan). This went hand-in-hand with the development of the ‘nation’ – i.e. a ‘group of people’ recognised as a nation could develop themselves ‘ethnically’, mainly by using their language as the official one. Many ‘nations’ then saw themselves as preferable owners of national autonomies (Molodikova 2016) because this predicts that the subjectivity of people should be complementary to the territory of their ‘origin’ (Brubaker 1996). Forced and wishful commonalities created a status of groupness because persons were labelled and included as a preferable group on the basis of their ethnicity in a specific territory.9 However, this juristic output did not apply to smaller ethnic groups or even huge minorities like Tatars or Gagauzes, who could not use their own language officially.

Inhabitants of the Soviet Union recognised nationality as asserted by Soviet policy, e.g. nationality was written on identity cards that were needed during negotiations with bureaucrats. Nationalities with ‘their own’ territory outside the Soviet Union could also receive identity cards with ‘their’ nationality (e.g. people of Polish origin who were signed as Polish; Iglicka 1998). People born in the Soviet Union could be assigned to a specific nation located outside Soviet territory (Brubaker 1996).

This is also the case for those of Czech origin living in the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. They were surrounded by others who were labelled Ukrainians and should therefore become accustomed to the Ukrainian majority, but could still be labelled as having Czech nationality. Indeed, they were able to speak Czech during informal meetings but official language rights were not accorded.10 According to this policy, Czechs were not given the same rights as Ukrainians and this was the first ‘obstacle’ for inhabitants of Czech origin. This was the first aspect which had a negative impact on Czech ethnicity (and subsequently on ethnic return migration) because Ukrainian and Russian nationality was preferred.

Proclaimed Russian and Ukrainian nationality in the Soviet era

During the Soviet period, inhabitants from mixed marriages could (at the age of 16) choose either their mother’s or their father’s nationality, without any choice of ethnicity other than those of their parents (Molodikova 2016). Such a decision had an impact on their personal career. Nationality was written on identity cards, pay-books or other personal documents (birth and death certificates, church register, etc.) and Russian and Ukrainian nationality was preferable as far as improved life expectations were concerned. Having an institutionally preferable nationality meant better access to education or employment (Brubaker 1996; Molodikova 2016), otherwise social mobility was very difficult. For the Czech diaspora, Russian or Ukrainian nationality was often more preferable than Czech nationality.

However, it should be mentioned that some inhabitants were institutionally forced – even as adults – to declare nationality as Ukrainian because they were indispensable to the local political structure as experts. This was the case for one participant’s father, who worked as an industrialist: ‘They took away (his) identity card and put him down as being of Ukrainian nationality. However, his documents proclaimed him as having Czech nationality. Even in (his) pay-book he was Czech’ (interview with H. N., Dubno, 17 July 2013). Bureaucrats, in some cases, decided on a person’s nationality which means that the possibility of someone choosing their nationality was somewhat limited.

Participants also mentioned that some Czechs were afraid to declare non-Russian or non-Ukrainian nationality due to the oppressive Soviet regime (see also Iglicka 2001). Those who had declared Czech nationality had problems with the Soviet security agency (KGB) and said that they were interrogated and suspected or accused of having enemy contacts abroad. The following conversation with T. S. in Dubno on 6 April 2012 goes back to the situation in 1939, after the Soviet invasion of East Poland:

L. H.: Your father was not Russian, but Czech. [Because] your grandmother was Czech. However, [your father] was declared as Russian in his passport, but he is Czech.

T. S.: Yes and he was written as Russian only in his passport. His mother is Czech.

L. H.: And it was written in passports that the mother was Czech and any children followed their mother.

T. S.: Yes, after his mother. But in 1939 he declared himself as Russian.

L. H.: His mother was Czech and he was written in his passport as Russian, because his father was Russian and [really] he is Czech.

T. S.: He had to, because they [the Soviets] arrived in 1939, so my Russian grandfather signed everyone [or our family] as Russian.

Some families even became accustomed to speaking in Russian or Ukrainian despite their subjective feelings of ethnicity. For example, in an interview on 8 July 2013, R. I., from Luck in the Ukraine, said that she was born in the Uman region and that both of her parents were Czech; however, they spoke only Russian so she had not been able to learn Czech until today: ‘My mother learned German as well as the Czech language, but she was afraid and did not talk [in the Czech language], so we were not able to learn our native language’.

Some participants also mentioned changing their original names to make them sound more Russian or Ukrainian and some others – as is expected – explicitly mentioned putting their nationality as Russian or Ukrainian on their identity cards or pay-books. In spite of these reasons, even during the Soviet regime, five participants declared their nationality to be Czech. Nevertheless, most referred to Soviet policy and its authority as a decisive factor in them choosing their nationality, which admits that ‘unfriendly’ Soviet policy was important and had an assimilative impact. Russian or Ukrainian nationality was preferred in the Ukrainian Soviet Republic and participants behaved in line with these nationalities to avoid oppression and to improve their lives. The breakdown of the Soviet Union and declaration of Ukraine independence in 1991 changed all this.

Proclaimed Czech ethnic consciousness after the dissolution of the Soviet Union

Ukraine’s unsuccessful transition from a planned to a market economy caused a huge economic crisis; political and economic turbulence in post-Soviet countries, including Russia, ushered in new preferences. Czech, Polish, Hungarian and other nationalities became more preferred than Russian or Ukrainian concerning people’s economic and social objectives.

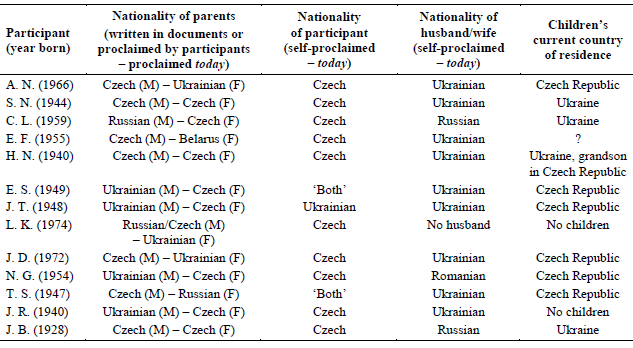

Table 2. Nationalities of participants and children’s country of settlement (2013–2014)

Note: Not all participants are in this table. Please note that these data were collected after ‘ethnic re-identification’.

Categories of nationality persisted in post-Soviet countries after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and had an impact on preferences, including those of members of the Czech diasporic association in Ukraine. They became citizens of their current country of residence – Ukraine – in 1991 but, roughly since then, most define themselves as belonging to the Czech nation. In justification, many of them talked about the improper declarations of their nationality which they had made during the Soviet regime. They said that their ‘true’ nationality was different and now defined themselves as ‘Czechs’, stating ‘We are Czechs’ even if not ‘clear Czechs’, but ‘mixed with Ukrainian nationality’ or have ‘one quarter Czech blood’. They ‘re-identified’ with Czech ethnicity even if they were originally from mixed marriages. As Table 2 shows, only three participants from the older/middle generation had parents who were both Czechs while ten had one Ukrainian, Russian or Belarusian parent; they mostly declared themselves as Czechs in spite of the mixed marriages of their parents. However, two participants declared that they could not be defined as either Czech or Ukrainian, because they live on ‘both sides simultaneously’ and one declared Ukrainian nationality. Table 2 also shows that participants from the middle generation mostly married Ukrainians (although two participants married Russians and one a Romanian); however their children (from the younger generation) had already declared Ukrainian ethnicity (even if they admired the Czech political system, for example). Nevertheless, the attractive economic and political conditions of the Czech Republic have crucial influence and even the young generation could apply for confirmation of belonging to the Czech diasporic community abroad and then for permanent residency in the Czech Republic.

Benefits for members of the Czech ‘diaspora’

Until 1996, members of the Czech ‘diaspora’ in Ukraine were treated by the Czech government as other Ukrainians; however, in 1996 the situation changed and Ukrainian citizens with Czech ancestors were positively viewed.11 They were then allowed to apply for documents declaring that they belonged to the Czech diasporic community living abroad and to receive benefits on the basis of their Czech origin and their membership in Czech diasporic associations.

These benefits included easier access to a Schengen (tourist) visa (the quick and successful provision of a visa provided by the Consulate General of the Czech Republic and the possibility of not having to pay the 35-euro fee for its preparation, although confirmation from the Czech diasporic association of their membership in the association was needed), the confirmation of multi-visas (multiple entrance into the Schengen area; residence in the Czech Republic for 90 days)12 and easier access to permanent residency in the Czech Republic (obtaining permanent residency in 6 months, together with the possibility of obtaining citizenship).13 However, having confirmation of belonging to the diasporic community abroad is necessary in all cases.

Indeed, all of the above is a kind of positive discrimination based upon the principle of ethnic affiliation. The affirmative treatment of Czech members of the ‘diaspora’ did not change even after the Czech Republic joined the European Union in 2004. The European Commission does not ban the positive discrimination of diaspora and the Czech Republic still allows the ‘diaspora’ living abroad to reap the benefits.

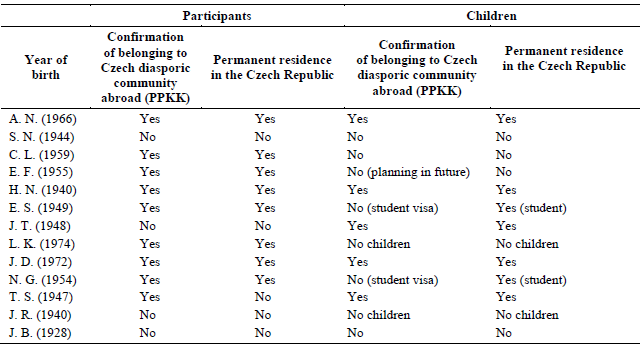

One of the strongest of those benefits is the opportunity to receive permanent residency in the Czech Republic for those who are able to confirm their membership in a diasporic community abroad14 and members of the ‘diaspora’ are able to settle in the Czech Republic much faster than other interested persons. Other Ukrainian citizens without this confirmation can obtain permanent residency only after five years of working or ten years of studying in the Czech Republic. This only confirms the importance of the Czech Republic’s immigration policy and legitimises the benefits available to the ‘diaspora’ as a strong pull factor.15 As Table 2 shows, six of my participants from the young generation live in the Czech Republic (plus one grandson) and only four live in Ukraine. In Table 3 we can see that four of these six participants living in the Czech Republic had written confirmation of belonging to the Czech diasporic community abroad and were thus able to obtain permanent residency (one was hoping to receive confirmation of belonging to the Czech diasporic community abroad in the future). Participants from the older and middle generations also now have permanent residency, although most of them remain in Ukraine.

Table 3. Confirmation of belonging to Czech diasporic community abroad and permanent residency (2013–2014)

Note: Not all participants are in this table. Not all participants necessarily have proof of belonging to the Czech ‘diaspora’ abroad nor of permanent residency – it depends on their documents and personal incentives.

In sum, young participants used the documents of their ancestors to gain permanent residency. However, some were prevented from ethnic return migration to the Czech Republic because of the official Russian or Ukrainian nationality stated in their ancestors’ documents. This policy in the Soviet Union could discourage ethnic return migration.

Declared Russian and Ukrainian nationality as a limitation to ethnic return migration

Crucial for the successful receipt of confirmation of belonging to a diasporic community abroad is the holding of appropriate (and not falsified) documents declaring Czech ancestors and proving a connection to them. It is practically impossible for participants to prove kinship from the period of Tsarist Russia (regime in Ukraine until 1917), so they can only prove it through documents from the interwar period, the era of the Soviet Union or the period of Ukraine independence up until 1996. Nationality in independent Ukraine16 could be altered by adult participants during the years 1991–1996. Since 1996, nationality is not recognised on identity cards, but is only stated on birth certificates (even today). This means ‘fewer opportunities for using’ ethnic ancestors. However, some participants managed to change their nationality in time to maintain the benefits for their children, as E. S., from Luck, told us in an interview on 18 April 2014:

I’ve got an identity card [with written Czech nationality]. On my first card I was Ukrainian. In 1970 my grandmother died. She spoke Czech and I promised her I would change my nationality. However, I was told it was not possible until 1991. So I changed my nationality to Czech in 1991. My cousin also changed his nationality; another cousin not. My aunts did the same – one changed her nationality, one did not.

What were the benefits for the children? Identity cards issued before 1996 were not returned to Ukrainians – the old photo of the person was just replaced by a new one and identity cards with a column for nationality remained unchanged, at least so I was told by my participants. These could be used as a document proving connection to a Czech ancestor.

For those aged 16+ in post-Soviet Ukraine who are the children of mixed marriages, they can choose the nationality they prefer from either of their parents’ nationalities. Today, however, it is possible for anyone to change their nationality in a court of law, and some older participants undertook it for the sake of their children. However, children’s nationality can be changed only to that of the second parent.17 An official avowal of Czech parentage in Ukraine has no impact on the obtain of confirmation of belonging to the Czech diasporic community abroad, because this proof is issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic and documented linkage to Czech ancestors is researched by the Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic. Nationality can be changed in Ukraine to ‘Czech’ but the applicant’s Czech origins need to be confirmed by the Ministry of the Interior; for my participants, documents from the Soviet era or the interwar period showing official Czech nationality were the most important for attaining permanent residency in the Czech Republic because they proved the applicants’ origins.

However, documents proving a person’s links to a Czech ancestor from the Soviet Union period (i.e. documents showing an ancestor’s Czech nationality) are often missing because Russian or Ukrainian nationality was preferred at that time. Only two participants had their father’s pay-book from the Soviet era with his Czech nationality acknowledged. The other 17 participants held documents from the interwar period (or documents issued prior to repatriation in 1947 – e.g. a marriage certificate from 1947) and five had no documents.18

Moreover, most participants had documents from the interwar period proclaiming the Czech nationality of a specific ancestor but were unable to prove a link with this person on their family tree due to missing or ‘misinterpreted’ documents from the Soviet period. For example, if the surname of a person’s grandmother differs on her birth certificate (she perhaps changed her name to sound more Russian), a link to her could not be proven. Indeed, very few people have all the documents – i.e. birth and marriage certificates, pay-books, etc.19 – which are necessary to prove a link to a Czech ancestor from the interwar period, as stated by L. K. from Luck in an interview on 13 May 2015:

His grandmother is written as Ukrainian, [his grandfather] as Ukrainian and he has only one very old document which shows the Czech nationality [of their ancestor]. They have only this one and [they couldn’t prove] the sequence by which that ancestor links to him. (...) I don’t know about others. My documents are ideal.

Some falsification of documents appears to be due to the positive immigration policy of the Czech Republic towards the ‘diaspora’ and the economic and social situation in Ukraine, as L. K. again asserts: ‘There was no Photoshop in 2001. Maybe there was, but not everyone could work with it. Right now, the Czech government has to check documents’. These were fictional attempts to get confirmation of belonging to a diasporic community abroad, thanks to the declaration of non-original documents or the stating of untrue information. The Czech Consul General in Lviv, M. K., said on 1 August 2014 that:

[The] number of diaspora has risen [in Ukraine] from 200 to 700 during a short period after the introduction of some benefits. It is not natural. Also, the submitted documents were fakes.

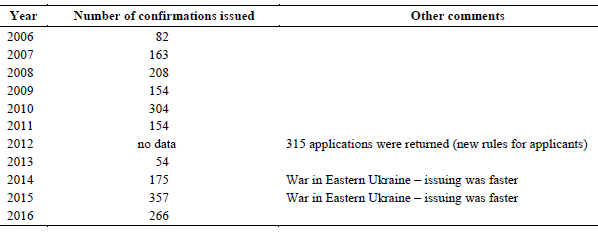

Paradoxically, as Table 4 shows, confirmation of belonging to the Czech diasporic community abroad is increasingly being issued – rising by more than 100 per cent between 2006 and 2014. We might conclude that more people have learned how to use ancestry to achieve permanent residency in the Czech Republic as this strategy was probably less-well known in 2006. This thesis is also supported by growing attempts to falsify documents. Consequently, it should be mentioned that the Czech diasporic association in Carpathian-Ruthenia enrolled 500 new members between 2014 and 2015, most probably because of the Eastern Ukraine conflict and new economic crisis in Ukraine, as the Czech Consul General in Lviv pointed out.

Table 4. Confirmations of belonging to the Czech diasporic community abroad (PPKK)

Note: Data are from the whole of Ukraine.

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic.

Declaring a specific nationality is a strategy for settling in the Czech Republic. During the Soviet period, Russian or Ukrainian nationality was favoured when seeking preferable treatment and social mobility. More recently, choosing the Czech nationality is a strategy enabling access to better life opportunities due to the distressed political, economic and social situation in Ukraine after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Euromaidan and the Eastern Ukraine conflict. This could be called ‘ethnic reidentification’ (Brubaker 1998). However, declaring Russian or Ukrainian nationality during the Soviet period limited a person’s chances of ethnic return migration – in other words, of attaining Czech ‘co-ethnicity’ and permanent residency in the Czech Republic.

Conclusion

Receiving states introduced more or less attractive criteria for immigration of members of the ‘diaspora’ – drawing up beneficial immigration policies toward them could trigger larger (or smaller) inflows of ethnic return migrants (Joppke 2005). The policy of the Czech Republic towards members of the ‘diaspora’ also implies ‘opening a door’ to the immigration of ‘co-ethnics’ living abroad. The effectiveness of policy on ethnic return migration in countries of immigration has been considerably researched (Brubaker 1996; Iglicka 1998; Joppke 2005; Tsuda 2003), yet the impact of policy on this kind of migration in countries of emigration remains somewhat understudied. Studies of ethnic policy in countries of emigration are rare and, even when mentioned (Brubaker 1996; Iglicka 1998), its consequences for migrant actions were never fully analysed.

My empirical research has shown that policies in countries of emigration – in this case the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Ukraine – must be considered. These policies resulted in fewer opportunities for migration success and discouraged ethnic return migrants. Crucially, Russian and Ukrainian nationality during the Soviet Union period was desirable because it supposedly assisted the development of a person’s career (education or job). However, the changing economic and political development in Europe after 1991 quickly changed migrant preferences (see Fedyuk and Kindler 2016) and at least the ‘Czech’ nationality is coveted in Ukraine to this day. Nevertheless, many Ukrainian citizens with Czech ancestors do not have in recently proper documents when applying for membership of the Czech diaspora. Main constraint is the Russian or Ukrainian nationality written on their documents or those of their ancestors. The expectations of participants remained the same

– well-being for themselves – but the desirability of countries is reversed and ethnic ‘reidentification’ (Iglicka 2001) – i.e. shifts in nationality after 1991 – means fewer opportunities for ethnic return migration even today.

Scholars have dealt primarily with the policy of the ‘ancestral homeland’ and its impact on generating ethnic return migration (Joppke and Rosenhek 2009), but this thesis has also its converse. Therefore, both immigration policies and policy in the country of a person’s birth affect the numbers of ethnic return migrants. They are not just persons who registered as members of the diaspora when the country of immigration ‘call’ to them and propose benefits (as scholars who studied ethnic return migration put it). Ethnic return migrants must also pass through constraints in the country of emigration, which could limit instrumental and strategic acting.

The circumstances analysed above may well also be common to other minorities in post-Soviet regions; they should not be applied only to Czech ethnic return migrants. The situation in West Ukraine did not differ from that in Kazakhstan, Belarus or Moldova, etc., because ‘European’ nationality might also be attractive in these countries – especially if their inhabitants have German, Polish or Estonian ancestors. Inhabitants of many post-Soviet countries could use ethnic ancestors to establish an ethnic disposition towards migration in very similar way but, again, their efforts could be thwarted because of the political situation during the period of the Soviet Union and the Russian (and one other preferable) nationality written in their parental documents.

Nevertheless, some constraints limit conclusion of this article. There are still differences about awareness of this possibility. First, the handling of nationality mostly took place in Czech diasporic associations and participants were often the most active members within them. They have a special interest in the activities in these associations and the improvement of members’ living conditions as well as the possibility of migration are two of the usual objectives. Second, even Czech descendants with proper documents have to overcome some constraints. Only a small number of participants among the whole ‘diasporic community’ possess the know-how to handle nationality. Others do not know how to bureaucratically ‘use nationality’ to their advantage. They have to ask others. To conclude, the strategy described above is one possible way, but one which not everyone is fully aware of or utilises it. Ukrainian citizens with Czech ancestors could be less responsive to this strategy and strategies pursued by them could differ.

Acknowledgements

I would like to especially thank Yana Leontiyeva from the Institute of Sociology of the Czech Academy of Sciences for her revision of this article. My special thanks also go to the two anonymous reviewers.

Funding

Institutional funding to support long-term strategic development (MSMT – 2013), The Charles University Research Development Schemes (PRVOUK) P20/2013/11, 2013–2014.

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID ID

Luděk Jirka  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2630-4550

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2630-4550

Notes

1 Danilicheva and Leonova (1997). Czech soldiers who fought in the Czechoslovak army corpus and settled in Czechoslovakia in 1945 were included.

2 This form of ethnic return migration is mostly connected with Eastern Europe (post-Soviet countries) and the Balkans and is common for Russian Jews or ethnic Germans from the Soviet Union and Russia (Brubaker 1998; Markowitz and Steffanson 2004; Tsuda 2009) and, to lesser extent, for ethnic Poles from post-Soviet countries (Iglicka 2001), Serbians, Bulgarians, Romanians and Croats in the Balkans (Waterbury 2014) or Greeks, Finns, Kazakhs or Russians from post-Soviet countries (Brubaker 1998).

3 Preferential immigration policy is also analysed in nationalistic terms, as the protection of persecuted members of the diaspora abroad (Brubaker 1998; Joppke 2005; Skrentny et al. 2007; Tsuda 2009; Waterbury 2014) or as an effort to reverse ethnic dispersion (Joppke 2005; Joppke and Rosenhek 2009).

4 Indeed, many countries do not actively support diasporic return, but do want to improve the living conditions of members of the diaspora in their countries of settlement.

5 The social and economic adaptation of ethnic return migrants in the country of immigration is also much studied. (Fox 2003, 2007; Kulu 1998, 2002; Kulu and Tammaru 2000; Skrentny et al.2007; Tsuda 2001, 2003). This is often seen as problematic because of the different internalised norms and cultural values, the paucity of knowledge about the situation in the country of immigration (Iglicka 2001; Tsuda 2009) or – explicitly stated – the different ethnicity (Fox 2007; Kulu and Tammaru 2000) even if some of them retain their ‘ancestral’ language (Kulu and Tamaru 2000) or religion (Iglicka 2001).

6 There is a difference between European countries and countries in East and South-East Asia. The latter attract members of the diaspora to work; they are invited for economic purposes as labour migrants (Tsuda 2009). For example, South Korea and Taiwan want high-skilled ethnic return migrants and South Korea and Japan attract low-skilled workers employed in 3D – or dirty, dangerous and demeaning – jobs (Skrentny et al. 2007). European countries tend to introduce more ‘romantic’ immigration policies and economic ties are seen as less important (Skrentny et al. 2007).

7 Describing political tensions in terms of diaspora between both countries is the right way (Skrentny et al. 2007; Waterbury 2014), but this is just a consequence of nationality policies.

8 There was one other repatriation in 1991–1993 because of the Chernobyl disaster. However, those repatriated were from the Zhytomyr and Kyiv regions and not from the Rivne or Volyn regions.

9 The status of groupness was invented by Soviet policy; Soviet ‘cabinet’ scholars and inhabitants were simply categorised. Even rare empirical fieldwork was not carried out, so that subjective expressions of ethnicity and self-determination were not followed (Allworth 1990).

10 Czechs could not gather officially during Soviet Era, but informal meetings proceeded in graveyard during funerals or visiting at home were the usual situations (participant S.N., Molodavo, Ukraine, 14 July 2013).

11 Czech diasporic associations were funded by a programme of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport together with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs which was designed to support Czech cultural heritage abroad from 1996 until 2001. Funds were mostly used for repairing original Czech buildings and objects, supporting Czech schools, libraries and festivals, teaching the Czech language and upholding Czech ethnic consciousness. From 2007 to the present day, these funds are distributed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs which also collects information about the ‘diaspora’ and Czech diasporic associations. Direct contacts with the ‘diaspora’ remain tained by employees of Czech embassies; they are often invited by Czech diasporic associations to festivals and other events.

12 This situation was changed by the introduction of a visa-free regime in 2017. However, Ukrainians still need biometric passports for a visa-free regime and this is also a problem.

13 Such benefits also include the awarding of special scholarships for Czech language courses in the Czech Republic (a one-month stay in Dobruška; one or two semesters at Charles University in Prague or Masaryk University in Brno).

14 Interesting benefits for its diaspora in Ukraine, Poland introduced the ‘Pole’s Card’, recognised in 2007 and Hungary the ‘Foreign Hungarians’ Card’, recognised in 2001 (Status Law). Polish and Hungarian cards accorded, among other things, the right to travel freely into the European Union.

15 This is more than visible in the case of Jews who migrated from Russia to Israel and Germans from the same country to Germany (Brubaker 1998; Joppke 2005; Markowitz and Steffanson 2004).

16 Ukraine guarantees political, social, economic and cultural rights to national minorities, and the development and self-determination of national minorities as basic human or political rights. Representatives of minorities could be elected to councils or other Ukrainians institutions, and national minorities are also financially supported by the Ukrainian government (Zakon Ukrajiny pro natsionalni menshyny v Ukrajini. Vidomosti Verchovnoji Rady Ukrajiny (BBR), 1992, No. 36, stattja 526/11). The rights of national minorities are also guaranteed by the Constitution of Ukraine, Rights of National Minorities in Ukraine and international agreements (Ukraine signed the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities declared by the Council of Europe).

17 Zakon Ukrajiny pro natsionalni menshyny v Ukrajini. Vidomosti Verchovnoji Rady Ukrajiny (BBR), 1992, No. 36, stattja 526/11.

18 For example, one lady from Dubno asked me to do her a favour, as she wanted to find a document concerning her great-grandfather in the archives in the Czech Republic in order to obtain confirmation of belonging to a diasporic community abroad. Nevertheless, even though she knew his name and birth place, my efforts were fruitless.

19 Searching for documents in archives (the state archive of the Rivne region and that of the Volyn region) was difficult before access to online research in 2008. Right now it is possible to find information about ancestors quite easily – just the name and date of birth of a person’s ancestors are needed to find any available documents. However, the actual information required is often missing.

References

Anghel R. (2013). Romanians in Western Europe: Migration, Status Dilemmas and Transnational Connection. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

Allworth E. (1990). A Theory of Soviet Nationality Policies, in: H. R. Huttenbach (eds), Soviet Nationality Policies: Ruling Ethnic Groups in the USSR, pp. 24–46. London: Casell.

Bauböck R., Ersbøll E., Groenendijk K., Waldrauch H. (2006). Acquisition and Loss of Nationality: Policies and Trends in 15 European States. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Brubaker R. (1996). Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brubaker R. (1998). Migrations of Ethnic Unmixing in the ‘New Europe’. International Migration Review 32(4): 1047–1065.

Brubaker R. (2006). Ethnicity Without Groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Castles S., Miller M. (2003). The Age of Migration. New York: The Guilford Press.

Cohen R. (1997). Global Diasporas: An Introduction. London: Routledge.

Danilicheva V., Leonova L. (1997). Chekhi na Volyni, in: Sim Dniv. State Archives of RivneOblast, fund P328.

Fedyuk O., Kindler M. (eds) (2016). Ukrainian Migration to the European Union. Cham: Springer.

Fox J. (2003). National Identities on the Move: Transylvanian Hungarian Labour Migrants in Hungary. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 29(3): 449–466.

Fox J. (2007). From National Inclusion to Economic Inclusion: Ethnic Hungarian Labour Migration to Hungary. Nations and Nationalism 13(1): 77–96.

Iglicka K. (1998). Are They Fellow Countrymen or Not? The Migration of Ethnic Poles from Kazakhstan to Poland. International Migration Review 32(4): 995–1014.

Iglicka K. (2001). Poland’s Post-War Dynamic of Migration. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Jaroszewicz M. (2015). The Migration of Ukrainians in Times of Crisis. OSW Commentary 187. Warsaw: Centre for Eastern Studies. Online: https://www.osw.waw.pl/sites/default/files/commentary_187.pdf (accessed: 20 December 2018).

Jaroszewicz M., Piechal T. (2016). Ukrainian Migration to Poland After the ‘Revolution of Dignity’: Old Trends or New Exodus?, in: D. Drbohlav, M. Jaroszewicz (eds), Ukrainian Migration in Times of Crisis: Forced and Labour Mobility, pp. 60–93. Prague: Faculty of Science, Charles University.

Joppke C. (2005). Selecting By Origin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Joppke C., Rosenhek Z. (2009). Contesting Ethnic Migration: Germany and Israel Compared, in: T. Tsuda (ed.), Diasporic Homecomings: Ethnic Return Migration in Comparative Perspective, pp. 73–99. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Kulu H. (1998). Ethnic Return Migration: An Estonian Case. International Migration 36(3): 313–336.

Kulu H. (2002). Socialization and Residence: Ethnic Return Migrants in Estonia. Environment and Planning A 34(2): 289–316.

Kulu H., Tammaru T. (2000). Ethnic Return Migration from East and the West: The Case of Estonia in the 1990s. Europe–Asia Studies 52(2): 349–369.

Libanova E. M., Poznjak O. V. (2010). Naselennja Ukrajiny. Trudova emihracija v Ukrajini. Kyjiv: Instytut demohrafiji ta sotsialnych doslidzhen.

Markov I. (ed.) (2009). Ukrainian Labour Migration in Europe. Lviv: International Charitable Foundation.

Markowitz F., Stefansson A. (2004). Homecomings: Unsettling Paths of Return. Maryland: Lexington Books.

Molodikova I. (2016). The Transformation of Russian Citizenship Policy in the Context of European or Eurasian Choice: Regional Prospects. Central and Eastern European Migration Review 6(1): 98–119.

Safran W. (1991). Diasporas in Modern Societies. Myths of Homeland and Return. Diaspora 1(1): 83–99.

Skalník P., Krjukov M. (1990). Soviet Ethnographia and the National(ities) Question. Cahiers du Monde russe et soviétique 31(2): 183–193.

Skrentny J., Chan S., Fox J., Kim D. (2007). Defining Nations in Asia and Europe: A Comparative Analysis of Ethnic Return Migration Policy. International Migration Review 41(4): 793–825.

Tsuda T. (2001). From Ethnic Affinity to Alienation in the Global Ecumene: The Encounter Between the Japanese and Japanese-Brazilian Return Migrants. Diaspora 10(1): 53–91.

Tsuda T. (2003). Strangers in the Ethnic Homeland: Japanese Brazilian Return Migration in Transnational Perspective. New York: Columbia University Press.

Tsuda T. (ed.) (2009). Diaspora Homecomings: Ethnic Return Migration in Comparative Perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Waterbury M. (2006). Internal Exclusion, External Inclusion: Diaspora Politics and Party-Building Strategies in Post-Communist Hungary. East European Politics and Societies 20(3): 483–515.

Waterbury M. (2014). Making Citizens Beyond the Borders: Non-Residental Ethnic Citizenship in Post-Communist Europe. Problems of Post-Communism 61(4): 36–49.

Vizitiv J. (2008). U poshukakh istyny: pereselnnja cheskoji etnichnoj spilnoty z Volyni u 1946-1947 rokakh na prykladi Dubenschyny, In: P. Smolyn (eds.), Chekhi i Dubenschyna, pp. 74-77. Dubno: Derzhavnyj istoryko-kulturnyj zapovidnik M. Dubno, Dubenske Cheske tovarystvo „Stromovka”.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.