Diverse, Fragile and Fragmented: The New Map of European Migration

-

Author(s):King, RussellOkólski, MarekPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2019, pp. 9-32DOI: 10.17467/ceemr.2018.18Received:

16 June 2018

Accepted:13 September 2018

Published:27 September 2018

Views: 13218

In this paper we review the significant political events and economic forces shaping contemporary migration within and into Europe. Various data sources are deployed to chronicle five phases of migration affecting the continent over the period 1945–2015: immediate postwar migrations of resettlement, the mass migration of ‘guestworkers’, the phase of economic restructuring and family reunion, asylum-seeking and irregular migration, and the more diverse dynamics unfolding in an enlarged European Union post-2004, not forgetting the spatially variable impact of the 2008 economic crisis. In recent years, in a scenario of rising migration globally, there has been an increase in intra-European migration compared to immigration from outside the continent. However, this may prove to be temporary given the convergence of economic indicators between ‘East’ and ‘West’ within the EU and the European Economic Area, and that ongoing population pressures from the global South, especially Africa, may intensify. Managing these pressures will be a major challenge from the perspective of a demographically shrinking Europe.

Introduction

In this paper, two long-standing students of European migration combine to explore the complexity of recent and current trends in international migration across the continent. Although we have long recognised and cited each other’s work, this is the first paper we have written as co-authors. It brings together an economist and a geographer whose perspectives are distinct yet overlapping and mutually reinforcing, for the economist appreciates the inherent spatiality and regional patterning of migration, and the geographer acknowledges the economic forces underpinning most migration flows and decisions. In any case, the quintessentially interdisciplinary field of migration studies, as sociologist Robin Cohen (1995: 8) has memorably emphasised, encompasses scholars from a number of disciplines (anthropology, economics, geography, history, sociology, etc.) who talk to each other across subject fields, languages and cultures, and whose research and writings are part of the webbing that binds global academic society.

Yet the research field of European migration has become intensely overcrowded as books and articles pour forth on an almost daily basis. Keeping up with this literature is a nigh-on impossible task, especially when fitted in alongside teaching, administrative duties and one’s own research and writing projects. This is not the place, not least because there is insufficient space, for a full listing of the significant books on European migration published in recent decades. However, very briefly and with apologies for the inevitably subjective selection, they range from the early classics of the 1970s (Berger and Mohr 1975; Castles and Kosack 1973; Piore 1979; Salt and Clout 1976), through a lean period in the 1980s and 1990s (eg. Blotevogel and Fielding 1997; Castles, Booth and Wallace 1984; Rees, Stillwell, Convey and Kupiszewski 1996), to a veritable explosion in the late 2000s and 2010s, much of this recent output driven by the flourishing IMISCOE network on ‘International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion in Europe’ (amongst many others, see Boswell and Geddes 2011; Favell 2008; Garcés-Mascareñas and Penninx 2016; Glorius, Grabowska-Lusinska and Kuvik 2013; Kahanec and Zimmermann 2016; Lafleur and Stanek 2017; Raymer and Willekens 2008; Recchi 2015; Recchi and Favell 2009; Triandafyllidou and Gropas 2014). The authors of this paper have made their own contribution to this growing library on European migration, editing or co-editing several books (Black, Engbersen, Okólski and Pantiru 2010; Bonifazi, Okólski, Schoorl and Simon 2008; King 1993b, 1993c; King and Black 1997; King, Lazaridis and Tsardanidis 2000; Okólski 2012a).

Nevertheless, we see value in standing back from the vast array of extant and continuously expanding literature and trying to map out European-wide trends in a way that will appeal to students and scholars seeking a concise overview combined with new insights into evolving patterns. In doing so, we are aware that there are three main ways of slicing up our subject matter: a historical approach which involves identifying chronological periods of more or less intense migration, a geographical approach focusing on countries, regions and the spatial pattern of flows and stocks of migrants, and a third approach which identifies different types of migration – labour migrants, highly skilled migrants, lifestyle migrants, retirement migrants, refugees and so on. Due to the cross-cutting nature of these different approaches, a simultaneous three-dimensional analysis would be difficult to achieve. Hence, we privilege the ‘historical waves’ approach as our primary classification, documenting how each period of migration is characterised in terms of geographical flows and migratory types.

Europe: a continent of immigrants

There can be no doubt that, over the past few decades, Europe has become an important destination for global migration. Tomáš Sobotka (2009) estimates that, during the half-century 1960–2009, the 27 EU countries (i.e. excluding Croatia) saw a net population growth, due to international migration, of nearly 26 million people, of whom 57 per cent arrived in the last decade of that period (2000–2009). According to a European Commission assessment, in around 2010 one resident in three in the EU had a more or less direct experience of migration (Eurostat 2011).1 The Commission also estimated that, in 2015, of the half-billion people living in the EU, 52 million – more than 10 per cent – were born abroad, and 34 million – 7 per cent – had foreign nationality (Eurostat 2016).

Parallel and similar data on European migration are available from the International Organization for Migration’s ‘World Migration’ reports, the latest being for 2018. This data compilation includes the whole of Europe, not just the EU, and is sourced from the UN Department for Economic and Social Affairs. According to IOM (2018: 18), Europe hosts 75 million, or 31 per cent, of the world’s ‘stock’ of 244 million migrants, substantially more than North America at 53 million or 21 per cent, although the US is the single largest host country with 47 million, followed by Germany, 12 million and the Russian Federation, 11 million. All the above figures are for 2015. Of the 75 million international migrants living in Europe in 2015, over half (40 million) were born in Europe. The non-European immigrant population, 35 million, originates from a wide diversity of mostly poor countries in Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Latin America (IOM 2018: 67–69).

As a result of a number of diverse and divergent economic, social and political processes in recent decades, the current configuration of the forms and directions of migration has become extremely complicated. Our purpose in this article is to explore this complexity. We start with a brief backward glance at the period before 1945 and then, in the main part of the paper, describe five phases of European migration within the seven decades spanning 1945–2015. We follow this by two further time-based assessments: an overview of current dominant trends and a speculative view of the future.

Main patterns of European migration before World War Two

Until the early postwar years, the European map of ‘contemporary’ international migration was relatively uncomplicated. By ‘contemporary’, in this particular historical context, we mean migratory movements that were triggered or sustained by accelerated population growth connected to the demographic transition that began in Western Europe at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Such an interpretation was advanced by well-known population scholars such as Wilbur Zelinsky (1971) and Jean-Claude Chesnais (1986), to create a systematic explanation and synthesis of these movements across a range of migration/mobility ‘transitions’. As a result of steady growth in the rate of natural increase, the majority of the regions of Europe affected by this phenomenon became overpopulated in terms of the prevailing technologies of production at that time. To survive, many people had little option but to migrate. ‘Modern’ changes in Europe’s economic structure – the emergence and expansion of industry and the related development of cities and industrial settlements – came to the rescue of this ‘excess’ population. A massive shift of people from over-populated rural to labour-hungry industrial areas took place, mainly within countries but also involving some cross-border migration. In terms of European macro-regions, this urban-industrial development was widespread in the western and northern parts of the continent; the southern and eastern regions lagged behind, as they still do today.

Focusing now on international migration, one safety-valve was offered by distant overseas countries, above all North and South America, which offered land-starved rural migrants the opportunity to occupy and cultivate larger swathes of land. Later, when North America industrialised, there was a need for inflows of industrial workforce. Meantime, the Europe of that era was, to a significant degree, made up of multinational empires – British, French, Dutch, Portuguese, Austro-Hungarian and the last vestiges of the Ottoman. Each had its own structures of metropolitan centres and colonised or occupied peripheries. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, a number of stable migration corridors were established, whereby the excess population from the imperial centres and pioneering ‘modern’ countries emigrated mainly across the oceans, while the vacant, usually unattractive and seasonal, jobs in those migrant-origin countries drew in ‘replacement’ migrants from the remaining, mainly peripheral parts of Europe.

Typical migration corridors established within Europe included the following. The Irish (before their mass exodus to America) migrated across the Irish Sea to Britain; the Portuguese and Italians to France (the Italians also, somewhat later, to Switzerland); the Norwegians, Danes and Finns to Sweden; and the Poles to Germany (and later also to France and Belgium). With the outbreak of the First World War, these intra-European migrations were accompanied, and often surpassed in terms of numbers, by transoceanic migration – especially to the US, Argentina and Brazil. These long-distance migrations, particularly to North America, were first drawn overwhelmingly from Northern and Western Europe; then, starting at the end of the nineteenth century, from Southern Europe; at the turn of the century and after, from Central and Eastern Europe (King 1996; Walaszek 2007).

Five phases of European migration 1945–2015

There have been numerous attempts to chronicle the evolution of European international migration post-1945 into a series of waves, stages or phases (see, for example, Bonifazi 2008; Castles, de Haas and Miller 2014; 102–125; Fassmann and Münz 1992; King 1993a; Triandafyllidou, Gropas and Vogel 2014; van Mol and de Valk 2016). Our periodisation presented here is in part a synthesis of other schemas and partly our own chronological categorisation in which we recognise, above all, the fact that European migration after the Second World War has taken place in the shadow of great political events. Undoubtedly the most important one, fundamentally shaping migration dynamics until as late as 1990, was the division of the continent into two opposing political blocs – ‘the East’ and ‘the West’ – divided by the Iron Curtain, which was not only a symbolic line separating two competing political, economic and existential ideologies but also a brutally effective migration barrier. Naturally the removal of that barrier, starting in late 1989, unleashed a new era of intra-European migration: in the words of Black et al. (2010), ‘a continent moving West’. Meanwhile, since the early postwar years, the Western bloc comprised two parts, defined by contrasting patterns of migration: the north-western – a magnet for immigration – and the southern – a reservoir of poorer people constrained to emigrate.2

Interwoven across the East/West binary have been other important political and economic processes which have impacted on the evolving map of European migration. Key here has been the formation, from its origins as the European Coal and Steel Community and then the Common Market in the 1950s, through progressive enlargements north, south, north again and then east of the European Union. With the ethos of the free movement of people – the so-called ‘fourth freedom’ after the free movement of capital, goods and services (Favell 2014; Recchi 2015) – EU enlargement as an ongoing process (Brexit apart) has correspondingly enlarged the ‘migration space’ across most of the continent. Even outside this space of free movement, from countries such as Ukraine, Moldova and Albania, emigration to EU countries has been intense.

Alongside these geopolitical changes have been important economic events – postwar reconstruction and the Fordist industrial expansion during the 1950s and 1960s; the oil crises of 1973–1974 and, less impactful, 1979–1980; another ‘long boom’ which lasted from the mid-1990s until 2008; and the economic crisis of the last ten years, from which recovery has been slow and patchy. Finally there have been ‘external shocks’, impacting on migration flows into Europe from the outside. The most dramatic of these was the so-called ‘migration and refugee crisis’ of 2015–2016, triggered by civil war in Syria, which set in motion a desperate stream of refugees into and through the countries of South-East Europe (see Crawley, Duvell, Jones, McMahon and Sigona 2018).

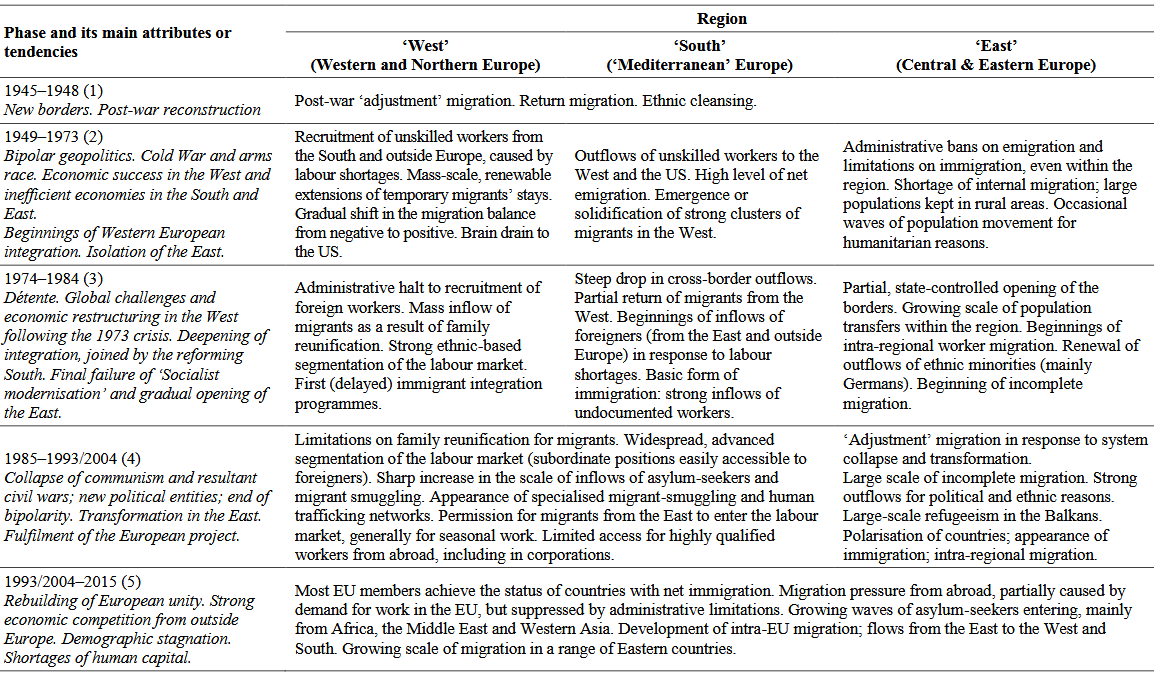

In Table 1 we attempt to synthesise the five main phases of European migration across the 70-year period in question. As prefigured in our introduction, the main division of the schema is chronological but we also separate out both the regional effects (for the ‘West’, ‘South’ and ‘East’ of Europe) and the main types of movement at each stage.

Table 1. Main phases of European migration and their characteristics, 1945–2015

Source: own elaboration based on Okólski (2012b).

Phase 1: postwar migrations of ‘adjustment’ and resettlement

The first phase, which lasted for a few years after the war and ended, in principle, in 1948, mainly concerned the movements of people who had been left outside their countries of (ethnic) origin as a result of war events, including displacement or the establishment of new state boundaries. Some of these ‘resettlement’ movements bore the characteristics of ethnic cleansing. These so-called ‘adjustment’ migrations were especially large-scale in Germany and in a range of Central and Eastern European countries (Fassmann and Münz 1995). Estimates for these migrations provoked by the disruptions of war and new state-building are necessarily imprecise but Kosiński (1970) suggests a total of 25 million people, noting that, by 1950, West Germany contained 7.8 million refugees and East Germany 3.5 million. In the face of the difficult living conditions caused by wartime economic destruction, transoceanic migration restarted, mainly from ‘peripheral’ European countries and continuing into the 1950s and even 1960s in some countries such as Portugal, Greece and Italy.

Phase 2: mass labour migration, 1950–1973

The second phase in the schema set out in Table 1 is connected to the economic process of postwar reconstruction and rapid industrialisation, which lasted until the onset of the first, and most sudden, oil crisis in 1973. It played out differently in the three macro-regions of the continent. In the USSR and its satellite countries, economic reconstruction was guided by a policy of autarky. The mobilisation of the workforce and the provision of growing industries with the necessary labour were possible thanks to huge internal transfers from agriculture and rural areas to centres of construction, extractive and heavy industries and manufacturing which were developing in large urban agglomerations, industrial districts and mining areas. With a few exceptions, the remaining countries of Europe became beneficiaries of the large-scale economic support of the US-financed Marshall Plan. Moving from reconstruction to sustainable economic recovery led to a sharply increased demand for labour but supplies of this crucial factor of production were unevenly distributed across Europe. North-West European countries suffered labour shortages, due to wartime losses, declining fertility in the immediate pre-war and war years, and increasing shares of young people entering tertiary education, delaying their entry into the workforce and moving their aspirations away from manual jobs. Southern European countries had higher fertility rates and excess labour resources, especially in rural areas beset by physical obstacles such as mountainous terrain, soil erosion and climatic drought. To address this problem of labour shortage, the stronger industrialising economies of Western Europe (principally the UK, West Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden and Switzerland) embarked on recruitment drives to import foreign workers (Bonifazi 2008; Collinson 1995). Two main groups of countries were involved as suppliers of migrant workers. The first group was Turkey and the Southern European countries – Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece and Yugoslavia (Livi Bacci 1972). The second was overseas colonial or former colonial territories in the Caribbean, Africa and South Asia. This latter group was especially important in the postwar pattern of labour recruitment to Britain but was also found in France and the Netherlands.

The mass labour migrations of the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s, which thus took place both within Europe and from outside the continent, had a profound effect on Europe’s overall migration balance, shifting it from a long-term historical pattern of net emigration to the rest of the world, to net immigration (Okólski 2012b). This ‘migration transition’ from negative to positive has continued ever since, although obviously not for all countries at all times.

One key aspect of Western Europe’s large-scale extraction of workers from other countries was the strategy of keeping them on a temporary status and employed on fixed-term contracts, thereby enabling the hosting states to claim that they were not ‘countries of immigration’. The West German Gastarbeiter (‘guestworker’) policy was the clearest example of this – a migrant-labour management system reliant on the short-term rotational employment of mainly male factory and construction workers, ruling out the possibility of them bringing in family members. This dehumanising treatment of migrant workers, which included accommodating them in hostels in crowded conditions, eventually gave way to a more socially responsible acceptance of the ‘human right to family life’ and opportunities for family reunion, which we include as part of the third phase of our historical model (see below).

Within the Southern European countries at this stage, a dual process of migration was under way. Part of the excess labour from the rural sector was transferred via internal migration to their own industrial centres but the majority went abroad (Livi Bacci 1972). This is most clearly seen in the case of Southern Italy where, over the period between the mid-1950s and the early 1970s, parallel out-migrations led north to fast-growing industrial centres in Northern Italy and to France, Germany and Switzerland as the main destinations for intra-European migration (King 1993d: 29–43). Italy at this time had the benefit of being a member of the original six-strong Common Market, so its citizens had the automatic right to move to the other five countries – France, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. For Turkey and the other Southern European nationalities involved in this vast labour migration system (Spain, Portugal, Greece and Yugoslavia), migration was orchestrated via bilateral recruitment agreements which shaped the evolving geography of flows and, ultimately, the settlement of different ethno-national groups in each host country. To take two examples of major destination countries, France drew its migrant workers mainly from Italy, Spain and Portugal (plus the Maghreb countries, especially Algeria), whilst West Germany recruited guestworkers from Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia and Turkey. On the whole, this migration geography was based on a combination of territorial proximity and colonial dependency. The main exception to this explanatory rationale was Turkey, far away from Western Europe and with no colonial ties. Yet, Turkey soon became the main source of foreign labour for West Germany and also initiated a lasting migration to several other European countries, including Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Austria. Notable, too, is the case of Yugoslavia, the only communist country that allowed its citizens to participate in labour migration.

At the same time as Western Europe ‘imported’ millions of guestworkers, barely granting them minimal rights to citizenship and long-term residence – at least initially – some of these countries enabled or encouraged the in-migration of ‘ethnic kin’ living in exile abroad, who were granted full citizenship rights in their ancestral home countries. Andrea Smith (2003) refers to these ‘repatriates’ as ‘Europe’s invisible migrants’, many of whom came back to the colonial mother countries as a result of colonial independence and expulsion in countries such as Indonesia, Algeria, Angola and Uganda. Key examples discussed at length in her book are the Dutch Overzeese Rijksgenoten, the French Pieds-Noirs and the Portuguese Retornados. According to Smith’s estimates, approximately 300 000 migrants arrived in the Netherlands from the ‘Dutch Indies’ between 1945 and 1963, 1 million French from Algeria in the early 1960s and 800 000 Portuguese from Angola and Mozambique in the mid-1970s (2003: 13–15). Between 1950 and 1989 the Federal Republic of Germany received 2 million so-called ethnic Germans originating mainly from the European communist countries (Frey and Mammey 1996). Later, in the extraordinary year of 1989, West Germany facilitated the move into the country on the cusp of unification (Kemper 1993) of the categories of Übersiedler (344 000 Germans from the GDR) and Aussiedler (377 000 ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe).

Phase 3: economic restructuring, family reunion and some return migration

For the Western sector of Europe, the economic downturn provoked by the oil crisis of 1973–1974 caused a significant drop in the demand for unskilled labour and the active recruitment of foreign workers was abandoned. Efforts were made to encourage those workers recruited in earlier years to return to their countries of origin – financial incentives were even offered – but with little effect overall. This was because, in the later years of the mass recruitment era, many workers had been able to repeatedly renew their temporary contracts, move into better housing and benefit from a relaxing of the exclusionary rules for bringing in family members. The result was a large wave of ‘family reunion’ migrants, coming especially from non-European countries such as Turkey and Morocco. Other migrants married and started families in their new countries of increasingly long-term residence, whilst yet others opted to stay on after 1974 rather than return-migrate, simply because they had nothing to return to in their home countries.

Whilst the closure and downsizing of many factories and construction sites in the wake of the recession rendered many migrant workers unemployed, some took the opportunity to move into other sectors of employment such as the catering industry and personal services (Blotevogel and King 1996; King 1997). Nigel Harris (1995: 10) argued that immigrants ‘allowed many native workers to escape from the worst manual labour. For example, in West Germany between 1961 and 1968, 1.1 million Germans left manual occupations for white-collar jobs, and over half a million foreign workers replaced them’. As the Fordist industrial structure was partially dismantled, becoming more flexibilised and decentralised, migrants sought to reposition themselves in selected niches within this post-Fordist segmented labour market. A typical move was to open a restaurant, snack bar or shop. Whilst for some this was a route to prosperity, for others it was a more precarious means of survival.

This phase also sees the first implementation of integration measures for migrants in North-West Europe. Paradoxically, the policy of integrating migrants became a way to block further immigration. Put slightly differently, one condition of success for integration policy was a restrictive immigration policy. Philip Martin (1993: 13) called this a ‘Grand Bargain’ by which governments seek to reassure restrictionist-minded publics that immigration is under control whilst simultaneously directing more attention to integrating and thus ‘deproblematising’ the immigrants who are already ‘here’ and unlikely to return to their countries of origin. This has meant that, over time, integration policy has shifted through the gears, albeit in a different way in different European countries. A common sequence has been to pass from simple measures to encourage incorporation and adaptation, to multiculturalism and then on (or back) to a more cultural assimilationist stance. As Rinus Penninx has written: ‘This new cultural conception of integration for migrants was a mirror image of how the receiving society defined its own “identity” (as modern, liberal, democratic, laicist, equal, enlightened, etc.). In practice, these identity claims are translated into civic integration requirements and mandatory civic integration courses of an assimilative nature for immigrants’ (Penninx 2016: 25).

Moving now to the South or Mediterranean Europe, the period between the mid-1970s and the end of the 1980s witnessed a series of far-reaching political and economic changes. Greece (in 1981) and Spain and Portugal (1986) acceded to the European Community, joining Italy – hitherto the only southern member – and thereby advancing their process of economic integration with North-West Europe. These countries also underwent deep political transformations, bringing their systems out of right-wing authoritarianism and closer to Western liberal democracy. Under the influence of good economic performance, there slowly began to appear in these countries the shortages of workers that had earlier been seen in the North-West. Key sectors of shortage were construction, agriculture, tourism and domestic and care work; much of this labour demand was in the informal economy, which was a structural feature of the Southern European economic system (King and Konjhodzic 1996). The signals from the labour markets of these four countries were so clear that, even without the support of government or para-state recruitment channels, inflows of foreign labour began, initially from beyond Europe and later, to a growing degree, from Central and Eastern Europe.

In the countries of the Eastern part of the continent, there appeared an inclination for greater openness towards the outside world, already presaged by Yugoslavia’s relaxed attitude to emigration dating back to the 1960s. Economic cooperation was sought with the West and most of the communist states signed up to the pan-European security system at the 1974 Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe. More exchanges took place in the fields of culture and education. As a result, in some of the Eastern countries and especially Poland, a liberalisation took place of many spheres of social life, including the cross-border mobility of people, which accelerated during the 1980s. During this period, intra-regional flows of workers also became quite popular. However, the key ‘opening’ consisted of travel and forms of ‘veiled’ or ‘proto-’ migration to the West. A typical arrangement was for tourist trips to enable contacts for work and business which later bore fruit in the form of informal migration (Okólski 2004).

Phase 4: the collapse of communism, growth in asylum-seeking and ‘irregular’ migration

The official blocking of further ‘legal’ immigration to Western Europe and the EU15 did not halt migration on the continent. Another wave of postwar migration, the fourth in our schema, dates from the end of the 1980s, a time which Castles and Miller, in the first edition of their landmark volume, identified as the start of their new ‘age of migration’ (1993: 2).

Several processes underpin the fourth wave. First, there was (and remains) the relative porosity of the EU’s southern border. With its long sea coast facing cross-Mediterranean access routes from North Africa, the southern EU countries were ill-equipped to stop both sea-borne migrants and others coming in by land and air on legal tourist visas but overstaying. Second, the buoyant informal economy in these ‘new’ countries of immigration, especially for casual jobs in construction, agriculture and tourism, offered multiple, if insecure and low-paid, job opportunities to migrants coming from poor countries who were desperate for paid work. Periodic regularisation schemes for these irregular migrants, which started in the mid-1980s in Spain and Italy and later in Portugal and Greece, helped to stabilise these rapidly expanding and diverse migrant populations, although they also arguably acted an incentive for more to arrive.

Third, more and more people arrived in Europe seeking humanitarian assistance, including refugee status. Until the mid-1980s, the annual number of asylum-seekers was of the order of tens of thousands but, by 1992, it exceeded half a million, most of whom were rejected. Illustrative of this overall increase is the case of Germany, the most popular destination for asylum-seekers: the number of people whose applications for refugee status were rejected grew almost seven-fold from 17 000 in 1985 to 116 000 in 1990, whilst the number of people to whom the status was granted fell by almost a half from 11 000 (65 per cent of applications) to 6 000 (5 per cent of applications) (Frey and Mammey 1996). A dual process was therefore being played out: on the one hand the criteria for acceptance were being administered more harshly, reflecting government policy to bear down on immigration numbers; on the other hand, increasing numbers of ‘ordinary’ or ‘economic’ migrants were pretending to be refugees.

The increased flow of refugees (most of whose ‘genuine’ nature could be questioned) resulted in large part from the collapse of the communist system across Central and Eastern Europe, from political turmoil on the south-eastern fringes of Europe and from the closure of popular and formerly accessible routes and forms of migration. This latter circumstance, which also included the tightening of rules for accepting asylum-seekers and granting them protection by many European countries in the early 1990s, sparked a sharp increase in irregular migration, including the clandestine transport of people across borders, often assisted by specialised international criminal networks (Salt 2000). The migration pressure from people in areas of origin – created by increased expectations fostered by migration networks and a specific ‘culture of migration’ instilled by earlier success stories of migrants – proved to be virtually unstoppable. Both the southern and eastern borders were also vulnerable to the irregular entry of migrants: the Southern European countries at this time operated a rather permissive control of their external borders, whilst controls along the continent’s eastern borders were weakened by the collapse of the communist regimes.

Summing up thus far, the processes described above across phases 2–4 created many changes in the map of European migration (cf. King 2002). From the late 1940s to the early-mid 1970s there was a dominance of inflows, initially constructed mostly as temporary, to North-West Europe; an inflow in which migrants from the European South and from former colonies largely prevailed. In West Germany additional important roles were played by numerically dominant Turkish migrants and by ethnic Germans living abroad ‘returning’ to their ‘homeland’. Over time, despite significant return migration related to economic downturns and to migrants’ personal life-stage plans, the guestworkers evolved into settled communities, although their integration into host societies was often a patchy process. The Southern European countries witnessed a remarkable migration transition from net emigration to net immigration: Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece in particular became targets for strong migration inflows after the 1980s, although the profile of the immigrants differed across each of these destinations. Whilst Italy and Spain received migrants from a wide range of African, Asian and Latin American countries, Portugal’s immigrant inflow came mainly from its former African colonies and Brazil, and Greece’s (after 1990) from Albania and Bulgaria (King 2000; Peixoto, Arango, Bonifazi, Finotelli, Sabino, Strozza and Triandafyllidou 2012). The East of Europe was largely cut off from these migration dynamics before 1990; however, after this date, substantial emigration flows were released. In proportion to their respective populations, outflows were particularly intense from the Baltic states of Latvia and Lithuania, from Poland and Slovakia and from Romania, Moldova and Albania. These outflows were directed, in different national combinations, to all parts of Europe – North, West and South (Okólski 2004).

Phase 5: diverse migration dynamics in an enlarged Europe

One of the most important political phenomena affecting recent migration processes in Europe has been the progressive integration of an expanding number of states into a single communal organisation embracing, eventually, 28 countries – or 27 pending the departure of the UK from the EU. Particularly significant was the creation, via the 1993 Treaty of Maastricht, of European citizenship in the newly named European Union and the guarantee to all citizens of the (then) EU15 of unlimited freedom of travel and relocation throughout the entire area of the EU, which thus became a de facto internal migration space. Yet it is worth remembering that the 1957 Treaty of Rome, which established the European Economic Community, also enshrined the principle of free mobility of human capital, albeit only applying to labour. Subsequently, it was the 1985 Single European Act which created the real basis for free movement across the EU, then in the throes of its second enlargement, for all citizens of member-states, initiating the process of removing internal borders as well as the physical, technical and tax barriers to mobility.

These geopolitical changes at the level of the EU created the need for the coordination of national migration policies, particularly in relation to citizens of third countries. As a result, there was a gradual unification of the rules for asylum and migration across the years 1997–2004, expressed in events such as the shift of those issues from the third to the first pillar of EU policy.

The project of a ‘deep and wide’ European integration creates the institutional framework for the fifth and final phase of postwar migrations in Europe, marked by a growing importance of intra-EU flows as well as by ongoing external flows into the EU and a diversity of forms and types of migration and mobility. Having said that, there is still a survival of the traditional understanding of migration policy in Europe as guided by a powerful resistance to the idea of the continent being an area of immigration. The notion of ‘fortress Europe’, as critics of the EU’s and its constituent states’ migration policy described it, is still relevant and stands as a counterpoint to the desire to deal with spatial disequilibria in growth rates and labour demand within the EU through fostering internal migration/mobility.

The need for a greater intra-EU mobility of labour to address geographical structural imbalances was stressed, inter alia, in the Lisbon Treaty of 2000 and prefigured the mass East-to-West mobility that was soon to occur following the 2004 enlargement (Black et al. 2010). At this time, eight Central and Eastern European countries joined (Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia), followed by two more in 2007 (Bulgaria and Romania) and Croatia in 2013. As a result, the EU28 became a huge area in which there is full free movement encompassing – let us repeat – half a billion people (EU citizens and also ‘residents’ originating from ‘third’ countries3), now integrated across the ‘old’ or ‘Western’ EU15 and the ‘new’ ‘Eastern’ EU11, plus two small new EU countries of the ‘South’, Malta and Cyprus. These people’s movements within this area are fundamentally internal migration, even though they cross (largely invisible) international borders.

Despite the institutional encouragement for more intra-EU migration, the region as a whole is characterised by relatively low population relocations. For example, in 2010 the share who took part in intra-EU migration between the 27 member-states was just 0.3 per cent of the entire population, i.e. fewer than 1 in 300; for migration on an inter-regional basis (NUTS first-level regions) within countries it was 1.0 per cent (Riso, Secher and Andersen 2014). For comparison, the rates for the United States were higher (2.4 per cent for inter-state migration, 1.2 per cent between four major US regions). Of course, we have to bear in mind that there are linguistic and other cultural barriers to movement within Europe. Even so, neoliberal economists such as Klaus Zimmermann (2014) have argued powerfully for more intra-EU migration to ‘repair’ spatial disequilibria, enhance overall European economic growth and maximise aggregate human welfare through access to better jobs and higher incomes.

Eurostat assessments based on measurement of migration according to a uniform criterion (arrival from another country and residence of at least 12 months) show that, over the period 2008–2014, the percentage of citizens of third countries among all newly admitted immigrants in the EU27 fell from 49 to 42 per cent (Eurostat 2016). Because the total number of immigrants remained almost identical (about 3.8 million), this means an effective drop in the total number of new arrivals from outside the EU and a corresponding increase in intra-EU flows.

On the other hand, despite restrictive EU policy on inflows of migrants from third countries, there is a range of ‘back doors’ through which non-EU migrants arrive perfectly legally (OECD and EU 2016). Here are seven of them, of which the first five are mainly subordinated to narrow economic interests:

- preferences or special privileges for scientists and specialists (Directives 2005/71/EC and 2009/50/EC);

- easier entry for interns and volunteers, and incentives to begin or continue tertiary education (e.g. Directive 2004/114/EC);

- easier conditions or ‘quotas’ for seasonal and circulating migrants (e.g. Directive 2014/36/EC);

- the permissibility or easing of inflows on the basis of special ‘regional neighbourhood’ agreements – e.g. as part of Eastern and Euro-Mediterranean Partnerships;

- easier procedures for ‘intra-corporate transfers’ (e.g. Directive 2014/66/EC);

- the right of foreigners legally residing in one EU country to bring to that country members of their immediate family (Directive 2003/86/EC); and

- the meeting of moral obligations by granting humanitarian aid (EU asylum policy).

The institutional measures listed above, allowing or promoting the inflow to the EU of citizens of third countries, have effects that go far beyond the intentions of these instruments. A clear example is EU asylum policy, which is certainly partially responsible for the so-called migration crisis that unfolded in 2015 and early 2016. At the outset, the common asylum policy significantly broadened the concept of the protection of vulnerable foreigners as specified in the Geneva Convention of 1951 and its subsequent protocol of amendment in 1967; the policy created a uniform requirement for member-states to ensure ‘subsidiary protection’ for foreigners who do not qualify for refugee status, regardless of the institution of humanitarian protection – optionally applied in specific countries and not uniform in context. However, this broadening was not accompanied by adequate logistical solutions for verifying foreigners’ rights to receive various forms of asylum or assistance, or for preventing non-entitled foreigners from entering or remaining within the territory of the EU. There was also a lack of common purpose and solidarity in the relocation of asylum-seekers between the countries with external EU borders facing the routes of flight and entry, and the remaining states. Whilst Germany and Sweden seized the moral high ground in welcoming these mainly Syrian refugees, other countries were either non-receptive (the UK) or openly hostile (Hungary). In the end, a cynical trade-off agreement between the EU and Turkey was signed in March 2016, by which Turkey took responsibility for preventing further boat migrations from its shores towards the adjacent Greek islands and for taking back new arrivals into Greece. The other side of the ‘bargain’ was a payment of 3 billion euros to Turkey, the promise of visa liberalisation for Turkish citizens and the re-energising of Turkey’s accession process (Crawley et al. 2018: 138).

Dominant patterns of migration in Europe today

In light of the analysis presented above, it is no surprise that today’s map of European migration comprises a mixture of different elements and patterns, some formed under the influence of recent political and economic events, others reflecting more-established migration traditions and their inertial effects reproduced over time. It is also the case that, beyond labour migrants and refugees/asylum-seekers, there exists a diversity of types of migration/mobility, as was pointed out by King (2002) in delineating ‘a new map of European migration’. King specified an increasing trend for independent female migration, more high-skilled migrants and international student mobility, new migrations borne of ‘crisis’, new regimes of shuttle and circular migration, a rise in north-to-south international retirement migration and, last but not least, a recognition that people migrate for romantic and emotional reasons – ‘love migration’.

To demonstrate the differentiation between old and new patterns, we use the results of our analysis based mainly on data for 2005–2014 sourced from the ‘SOPEMI’ network and published in the latest International Migration Outlook 2017 (OECD 2017).4 By focusing on this decade, we start from the ‘historic’ year of 2004 when the major eastward enlargement of the EU took place and the European area of free movement was substantially extended, corresponding to the fifth phase of the scheme presented above. Our quantitative data refer to annual averages for the period in question. The analysis covers 26 countries which are part of the European Economic Area (EEA) plus Switzerland, for which data were available on the structure of inflows by country of origin.5 Later, we elaborate separately on the geographic pattern that emerged in 2015.

The first key finding is that there has been a notable increase in international mobility both into but particularly within Europe. For the latter trend, the key date was the first main ‘Eastern’ enlargement of 2004. Baláž and Karasová (2017) measure this by comparing the average annual stock of intra-European migrants during 1997–2004 (9.1 million) to that of 2005–2013 (13.7 million), a growth of 52 per cent in unrounded figures.

Second, a large majority of countries which were already established as net immigration receivers have continued as such. Again according to Baláž and Karasová (2017: 7), a ‘rich club’ of six main migration destinations (UK, France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy and Spain) received 75.4 per cent of all intra-European migrants during the two periods specified above, whilst 15 destinations (the above six plus Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden) attracted 95.9 per cent in the pre-2004 period and 95.8 per cent in the post-2004 period. This stability in the pattern of destinations occurred despite the overall increase in total migrant stocks noted above, the rising unemployment and the fact that some of them were going through economic difficulties as a result of the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and after. The worst affected by the crisis were Greece, Portugal, Spain and Ireland, whose migration balances – positive before the crisis – turned negative after, although a positive balance was restored in Spain in 2015 and Ireland in 2016. In addition, a group of ‘Eastern’ countries where post-2004 emigration was not as pronounced – Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia – has gained a positive migratory balance and joined the group of European net immigration countries. Finally, in most of the countries not yet mentioned above – viz. the ‘Eastern’ countries of Bulgaria, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania – emigration has been continuously dominant since 2004, albeit at fluctuating rates over time and between these different source countries. These trends are either directly evident from the OECD and Eurostat sources already cited, or are deducible from other sources.

If we now turn back to Baláž and Karasová’s (2017) illuminating analysis, which is restricted to intra-European migration based on 31 countries (the EEA countries, minus Lichtenstein and plus Switzerland), three other interesting trends are uncovered beyond the overall 52 per cent increase in migrant stocks over the pre- to post-enlargement periods. First, their network diagrams of the origins and destinations of migrant stocks show the important rise of the UK, Spain and, less markedly, Italy as key destinations post-2004, whilst Germany maintains its position as the largest stock-holder of migrants across the two periods in question. Significant increases in stocks were also recorded by France, Switzerland and Belgium, though at much lower absolute levels. Second, the proportionate increase in migrant stocks is disaggregated by the four possible flows between the European ‘centre’ and its ‘periphery’.6 The largest increase was for periphery-to-centre flows – 109 per cent – or from 3.12 to 6.52 million. The lowest increase – 19 per cent – was for centre-centre flows, from 5.57 to 6.64 million. The two other flows, much smaller in absolute scale, were from centre to periphery (0.13 to 0.22 million, an increase of 68 per cent) and from periphery to periphery (0.24 to 0.35 million; 44 per cent). Third, Baláž and Karasová draw out some specifics of the changing geography of flows between clusters of origins and key destinations, based (but not always) on factors such as geographic proximity and language similarity. They confirm four major ‘modules’ based on nodes and supplies: (i) the Germany-centred module, supplied by Austria, Hungary, Italy, Greece and Poland, (ii) the UK-based module, which combines the traditional contribution from Ireland with new inflows from Poland, Slovakia and the Baltic republics, (iii) a Southern EU module, with Italy and Spain fed by major contributions from Romania and Bulgaria, and (iv) a weaker and more diffuse French-Belgian-Dutch module.

Our own analysis confirms and complements this by combining EEA migration with third-country origins and making a comparison between these two source areas for migrants in Europe. This leads us to three major conclusions. Firstly, in the majority of countries, nationals of the EEA dominated, often comprehensively so. Referring to the period 2005–2014, in Iceland, Slovakia and Switzerland, nine of the top ten foreign-migrant nationalities were from the EEA; in Luxembourg, eight; in Austria, Belgium and Denmark, seven; and in France, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK, six. In Iceland, Luxembourg and Switzerland, EEA nationals accounted for between two-thirds and three-quarters of all incoming migrants. At the other extreme there is Greece, where no EEA country figures in the top ten incoming migrant nationalities, whilst Italy and Poland have just one and Finland, two.

Secondly, in the majority of countries, there was a considerable diversity of immigrant countries of origin. Greece remains, once again, the extreme exceptional case: most of the immigrants to this country are from neighbouring Albania.7 Slovenia, Romania and Hungary are also at the monoethnic end of the spectrum, though these are countries with only small inflows from abroad. Their majority inflows are, for Slovenia, 39 per cent from Bosnia and Herzegovina; for Romania, 37 per cent from Moldova; and for Hungary, 35 per cent from Romania. Otherwise, in no country did the share of the largest country of origin exceed 30 per cent – in 12 of them it was less than 20 per cent. In the main countries of net immigration (except Switzerland), the share of the five leading countries of origin did not exceed 50 per cent; in most cases it oscillated within the range 30–45 per cent, reinforcing the principle of diversity or, as Steven Vertovec would have it, ‘super-diversity’ in migrant origins and characteristics (2007).8

Thirdly, an undeniably important role in the geography of inflows over the post-enlargement years 2005–2013 has been still played by migrants coming from outside the EEA and Switzerland. For the 26 countries of destination for which comparable data were available for the period in question, and amongst the list of top ten origin countries, there were 30 non-European countries, including just two highly developed ones (the US – in the top ten in five destinations countries – and Australia, in just one destination – the UK). Amongst the origin countries that appeared the most often in the 26 top ten lists were China (in 11 countries), India and Syria (8), the US and Iraq (5) and Afghanistan and Morocco (4). As many as 18 of these 30 sending countries featured in the top ten of origin in at least one of the 26 receiving countries.

In synthesis, in the geographical domain under consideration, we distinguish four main migration channels:

- intra-EU, from East to West, or more precisely from the ‘new’ EU countries (EU 10+2+1) to the ‘old’ EU countries (EU15) plus Switzerland, Norway and Iceland;

- intra-EU but limited to migration between adjacent countries (e.g. Ireland-the UK, Germany-Switzerland, Austria-Germany, etc.);

- migration from non-EU European countries; this covers two subtypes: migration to ‘old’ EU countries (e.g. Albanians to Italy and Greece) and migration to ‘new’ EU countries (e.g. Ukrainians to Poland and Slovakia); and

- migration from outside Europe.

A typical attribute of this four-fold geography of migration is that, in any given destination country, only one of these types is usually dominant; it is rare for two or three to occur on a similar scale.

The two intra-EU channels became the basic element in the newest mosaic of European migration. For Germany, the country with the largest labour market, Penninx (2016) points out that, over the period 2004–2011, the share of migrants arriving from EU member-countries increased from half to almost two-thirds. Meanwhile, Riso et al. (2014) showed that, during the period of the economic crisis (2008–2010), the employment of domestic-origin labour in the EU27 fell by 5.8 million (2.5 per cent) and of citizens of third countries by 272 000 (3 per cent) whereas the employment of citizens of other EU countries grew by 828 000 (14 per cent). Scrutinising these opposing tendencies, Riso et al. (2014: 18) concluded that ‘in an enlarged EU, and largely as a result of strong east-west flows, intra-EU mobility has replaced mobility from non-EU countries as the main source of migrant workers in the EU’.

During 2005–2014, the number of migrants from the ‘new’, post-2004 EU member-states who were resident in the 15 ‘old’ member-states at least doubled, although this increase was much higher in some countries – notably the UK – where it increased thirteen-fold, Denmark (nine-fold), Belgium and the Netherlands (six-fold), Luxembourg (five-fold), Italy (four-fold) and Germany (three-fold). The greater ‘responsibility’ for this growth came from two ‘new’ EU countries, Romania and Poland, respectively with 2.5 million and 1.8 million of their citizens established in other EU countries – the Romanians mainly in Italy and Spain, the Poles mainly in the UK and Germany. A different dataset from the EU Labour Force Survey shows that, for the period 1998–2009, the most significant outflows, measured in relation to the population of the country of origin, were from Romania (8.9 per cent). Lithuania (4.8 per cent), the Czech Republic (4.7 per cent) and Bulgaria (3.7 per cent); see Fihel, Janicka, Kaczmarczyk and Nestorowicz (2015).

As we indicated earlier, intra-EU mobility has a dual character: alongside the flow of migrants from the ‘new’ to the ‘old’ EU states, meaning East to West, it also involves movements into and between neighbouring states, often of higher-skilled migrants. Typical ‘neighbourhood effects’ are clearly evident in the following receiving countries (those in parentheses are the ‘suppliers’ within the top five origins for each destination): Luxembourg (Belgium, France, Germany), Switzerland (France, Germany, Italy), Austria (Germany, Hungary), Belgium (France, the Netherlands), Czechia (Germany, Slovakia), Denmark (Germany, Sweden), Finland (Estonia, Sweden), France (Italy, Spain), Slovakia (Czechia, Hungary), Estonia (Latvia), Germany (Poland), Latvia (Lithuania), Lithuania (Latvia), the Netherlands (Germany), Norway (Sweden), Poland (Germany) and Sweden (Finland).

Migration from outside the continent of Europe originates from a diversity of countries across the globe, especially from Africa north and south of the Sahara, South and East Asia and Latin America. If we once again refer to the criteria of the five largest migrant supply countries, we uncover a pattern which is rather ‘specialised’ along specific origin-destination channels. The Chinese, who are the most numerous nationality among migrants from third countries, have the most diversified ‘geographic portfolio’, being in the top five immigrant groups in several receiving countries – Finland, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and the UK. Moroccans are likewise quite widely spread – amongst the top five in Belgium, France, Italy and Spain. The remaining non-European groups were in the top five in one or two destination countries: citizens of Iraq in Finland and Sweden, Somalia in Norway and Sweden, and Vietnam in Czechia and Poland with, finally, Algeria and Morocco in France, Australia and India in the UK, Brazil and Cape Verde in Portugal and Colombia in Spain.

For the final remaining group – non-EU Europeans, less numerous overall – the two key origins are Ukraine and Albania. Regarding the receiving countries in the ‘old’ EU, Ukrainians are within the top ten immigrant groups in Italy and Spain; Albanians in Germany, Greece (in Greece they are by far the most numerous group of immigrants) and Italy. Additionally, in Austria, Serbians are within the top ten and, in Finland, Russians are. It is worth recalling that there is also a ‘neighbour’ effect across the newly repositioned EU/‘East’ divide. Thus Ukrainians are the most numerous immigrant group in Poland; they are second in Czechia, Estonia and Latvia, and third in Hungary, Lithuania and Slovakia. A similar role is played by migrants from Belarus (in Poland and Lithuania), Russia (in Czechia, Estonia, Lithuania and Poland), Moldova (in Romania) and Serbia (in Hungary and Slovenia). Slovenia is something of a special case as, here, three of the four largest immigrant groups come from the countries of the former Yugoslavia, headed by Bosnia and Herzegovina.

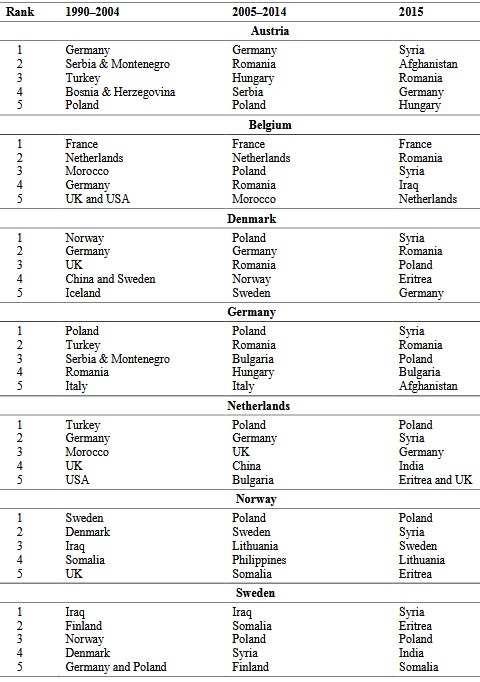

In the final part of this overview of the main patterns of migration in today’s Europe, we take a brief look at the unexpected changes in 2015 and after which introduced new elements into the geographic composition of the inflows into seven ‘important’ EEA countries. Indeed, vehement intensification of the inflow of asylum-seekers into the Schengen Area resulted in an almost immediate rise of new residents from among those new arrivals in several EEA countries. Statistics of immigration flows that were recorded in 2015 in 28 European countries under consideration reveal a fundamental change of their geography in seven countries – Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden – which is evidenced in Table 2. The table juxtaposes the top five countries of origin in 2015 and preceding periods (1990–2004 and 2005–2014). In these seven countries, Syrians have become the major immigrant nationality.9 In four countries a significant role has been assumed by people from Eritrea10 and, in two, by people from Afghanistan.11 None of those nationalities played an important role in the inflows to the seven countries in 1990–2004 and (with exception of Syrians in Sweden) 2005–2014. In turn, amongst the top five countries of origin, a spectacular decline of importance occurred in the case of Turks (Austria, Germany, the Netherlands), Moroccans (Belgium, the Netherlands) and (rather surprisingly) citizens of Iraq (Norway and Sweden). Tentative estimates for 2016 and 2017 tend to confirm a new pattern that emerged in these seven countries in 2015.

Table 2. Top five sending countries in selected European Economic Area countries; 2015 compared with 1990–2004 and 2005–2014

Source: OECD, International Migration Outlook, various years.

Contrasting with those changes was the stability of the geographic pattern of inflows in a majority of remaining countries, particularly the largest (besides Germany) European immigrant receivers: France, Italy, Spain and the UK. France traditionally adhered to flows from Mediterranean countries (with the unchallenged lead of Algeria and Morocco), in Italy and Spain, Romanians followed by Moroccans retained their primacy (with a minor reshuffling of other important countries of origin) while, in the UK, amid rather ‘cosmetic’ changes, Romanians spectacularly moved from seventh position to the very top. All countries, including those receiving relatively fewer immigrants – such as Czechia, Iceland, Portugal, Slovenia and, above all, Switzerland – turned out to be somewhat immune to the unprecedented increase in the inflow of asylum-seekers from Afghanistan, Eritrea and Syria, at least in view of their migration statistics.

What next?

As we have attempted to demonstrate, the geographical directions and size of migration flows observed in Europe over recent decades and today are the result, to a large degree, of political conditions. These conditions change, both in an evolutionary way and, sometimes, quite suddenly. One of the most notable trends over recent years has been the increase, in both relative and absolute terms, of intra-EU mobility resulting from the eastward expansion of the EU. This has brought out into the ‘open market’ geographic contrasts in economic wellbeing between the ‘West’ and the ‘East’ of the EU which can now act as incentives to migrate under the free movement provisions of the EU. However, this can be brusquely interrupted, as shown by the UK’s 2016 referendum result and the ensuing decision to leave the EU, which is already affecting the direction and scale of movements to and from the UK, including with the UK’s main ‘new’ EU migration supplier – Poland (Lulle, Moroşanu and King 2018; McGhee, Moreh and Vlachantoni 2017).

In fact, the weakening or even reversal of existing patterns and directions of intra-European migration may be supported by other circumstances, the long-term significance of which should not be underestimated. One of these is the narrowing of the gap in living standards between the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ EU. For instance, during the period 2000–2014, GDP at constant prices12 grew in the EU28 by 21 per cent yet, in Poland, the growth was 67 per cent, with a similar increase in the Czech Republic and Hungary. In fact the difference between GDP growth rates per capita was even greater because, whilst the overall EU population was growing, that of Poland declined. The gap also shrank in subjective perceptions of life challenges. Over the period 2005–2012, the percentage of households making ends meet ‘with (great) difficulty’ grew in the EU as a whole from 25.4 per cent to 27.7 per cent whilst, in Poland, the share fell from 51.2 to 34.2 per cent (CSO 2014). There are strong reasons to believe that the economic distance between the ‘West’ and the ‘East’ of the EU will continue to narrow, thereby disincentivising migration; indeed, taking into account the improving quality of life and still-low cost of living in the ‘East’, East-West moves might even be reversed. The precedent is the much earlier ‘Southern’ enlargement of the EU in the 1980s, which helped to advance the economic indicators in Spain, Portugal, Greece (and Italy), bringing then much closer to ‘European’ levels from their prior ‘backward’ state (King and Konjhodzic 1996).

The second circumstance arises from ongoing and future demographic trends, which are much more predictable than economic scenarios and political events. According to Eurostat projections, over the fifty-year period 2010–2060, there will be a decline in potential labour supply (persons aged 15–64) of 15 per cent across the EU. This decline will be more marked in the ‘new’ member-states than it will in the ‘old’ ones where, in many cases, the internal labour reserve will increase. To take some specific examples, a predicted labour force growth of 10 per cent in the UK and 8 per cent in Sweden contrasts with decreases of around 40 per cent in Poland, Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria – in the latter cases due to the combination of young-adult emigration and falling (and sub-replacement) birth rates (Giannakouris 2008). Whilst evening out these growth imbalances is potentially one benefit that can be reaped from migration, this can also be viewed as a kind of ‘demographic engineering’ in order to rejuvenate a population, which may have only short- to medium-term effects and have problematic ethical implications (King and Lulle 2016: 19–20).

The part of the world destined to experience further long-term population growth – in contrast to other continents where population growth is decelerating – is Africa. Although there has been a long postwar history of emigration from the Maghreb to Europe, emigration from sub-Saharan Africa is still at an embryonic stage. Meanwhile, according to UN projections, Africa’s population will more than double – an increase of almost 1.3 billion people – over the fifty years 2015–2065; at the same time, Europe’s will decline by 50 million or 6 per cent (UN 2015). It is difficult to imagine that the ‘logic’ of migration pressure between these two adjacent continents, separated only by the Mediterranean ‘Rio Grande’, will not lead to increased flows – either managed or spontaneous and irregular (Montanari and Cortese 1993).

Other migration pressures bearing on Europe arise from the waves of irregular migration that follow political conflicts such as civil wars and ethnic cleansing in different parts of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. When such civil or international conflicts erupt, the boundaries between those who can be defined as genuine refugees and those who, in reality, are plain economic migrants fleeing poverty or who simply want to ‘be’ in Europe, become blurred. For example when, in 2015, the massive flows of Syrian refugees pouring out of their strife-torn Syrian cities and those living in camps in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon were set in motion, they were instantly joined by tens of thousands of ‘pseudo-refugees’ from other countries, seizing the opportunity to make it to Europe – which otherwise would be closed to them. According to Eurostat data, of the 1.26 million asylum requests made in European countries in that year, only 28 per cent were filed by Syrian citizens; 39 per cent came from migrants from Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Albania and Kosovo, whilst the remaining 33 per cent were from people from dozens of other countries (Eurostat 2016).

Of course it is also true that the Syrian refugee crisis was exacerbated by the EU’s inability to orchestrate coordinated action in the face of the large numbers arriving across the narrow stretch of sea separating the Western Turkish coast and nearby Greek islands, and thence via the ‘Western Balkan route’ into Central and Northern Europe. It also revealed the political and humanitarian divisions between ‘welcoming’ Germany and Sweden and the defensive and even racist reactions of some of the Central and Eastern EU countries, led by Hungary.13 Indeed, it seems that attitudes towards immigration and multiculturalism constitute a new cleavage separating some of the Western EU countries, with longer histories of immigration, and the new member-states, which are much less open to large-scale immigration or accommodating refugees (Lulle 2016).

Migration pressures from third-country citizens, especially from Africa, will probably also strengthen because of the ‘demonstration effect’ or the line of thinking which asks ‘If they could do it, why can’t we?’ This effect is amplified by the forces of globalisation, especially in the realms of culture and communication: the uniformalisation of symbolic codes and mass cultures, the development of information technologies and increasing access to efficient means of transport.

Conclusion

The ‘map’ of recent, current and future migration in Europe sketched out in this article does not present a very stable picture. In truth, it is a combination of some stable patterns inherited from the past, overlain with new, diverse processes, some of which are likely to be ephemeral and others more long-lasting. On the one hand, as we have seen with the Syrian refugee crisis and with the ongoing desperate migration flows across the Mediterranean from North Africa, Europe – especially Southern Europe – continues to be the ‘soft underbelly’ for global movements of asylum-seekers and for many other population movements driven by strong feelings of deprivation among the residents of poorer parts of the world. The failure of migration policy to strike a balance between humanitarian morality, labour market and demographic needs and a sensible and effective management of inflows, bears some responsibility for this.

On the other hand, changes are afoot within Europe – and especially the EU – which will also probably reshape future migration trends. Here the ongoing economic improvement of the post-2004 member-states will be key: not only the objective economic indicators such as real incomes and employment trends but also issues of quality of life and the perceptions and aspirations of the younger generations who will wish to be mobile but not necessarily to migrate. It thus remains to be seen how long the ‘East’ of Europe will sustain its function as a labour reserve for the ‘West’ of Europe, especially bearing in mind the future demographic scenario of a shrinking population. Brexit remains another unknown element in the future map of European migration. Although controlling immigration from Europe was a major rhetorical plank in the ‘Leave’ campaign, the success of the British economy will continue to depend on supplies of flexible migrant labour across a whole range of sectors, from agriculture to tourism to health services.

The indicators, then, are that the inequalities and future trends in population and labour force potential and demographic dynamics will ratchet up the migration pressure on Europe from the populations of the global South – both those who are desperate to escape poverty and those who have more middle-class aspirations for mobility. It remains an open question whether Europe will be able to resist and manage these pressures in a more efficacious manner than hitherto.

Notes

1 To be more precise, more than 20 million people were citizens of ‘third’ (i.e. non-EU) countries, 50 million had citizenship in an EU country but had been born abroad, 25 million – though born in an EU member-country – had parents or grandparents born in another country and, finally, an additional 55 million had earlier experienced long-term stays abroad for work or studies (Eurostat 2011: 78).

2 This north/south division of Western Europe is not absolute. Ireland (with its large-scale emigration to Britain) and Finland (migration to Sweden) interrupt this division, leading some to suggest more of a core/periphery (see Seers, Schaffer and Kiljunen 1979).

3 Such ‘residency’ usually involves legally living in the territory of the EU for at least five years.

4 The SOPEMI ‘continuous reporting system on European emigration and immigration’ is a long-running organ for collecting and synthesising annual migration data – both flows and stocks – and is widely used by migration researchers who value its systematic recording of trends over time and its critical approach to the data sources used.

5 The EEA comprises all 28 EU countries plus Norway, Iceland and Lichtenstein. However, in our analysis no comparable data were available for Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland, Lichtenstein and Malta. Data for Greece refer to 2003–2011 (OECD 2015).

6 For this analysis, Baláž and Karasová define ‘centre’ as made up of the following 15 countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK. The remaining 16 countries in their dataset are classed as ‘periphery’.

7 Inflows from Albania to Greece are not well recorded, since a lot of the migration has been clandestine and also seasonal or temporary. However, various Greek and Albanian sources indicate a stock of around 500 000 Albanians in Greece although, in recent years, the severe Greek recession has probably reduced this number as a result of return and onward migration (see Barjaba and Barjaba 2015; King and Vullnetari 2012).

8 Beyond Switzerland as a main immigration country, the same holds for other net-immigration countries (Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Iceland and Luxembourg) although these are not major players in the new map of immigration in Europe.

9 In addition, in 2015, immigrants from Syria appeared in the top ten countries of origin in Finland and Luxembourg (taking, in both countries, the eighth position).

10 In another country of destination listed in Table 2 (the Netherlands), Eritreans figured as No. 7.

11 Moreover, in Belgium and Sweden they took position No. 6.

12 Standardised by ‘purchasing power parity’ (PPP); data from Eurostat (http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/national-accounts/data/main-tables).

13 This contrast was partly created by the decision of the German government to open its borders to offer shelter to incoming Syrian refugees a priori – i.e. before determining their eligibility.

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID ID

Russell King  http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6662-3305

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6662-3305

Marek Okólski  http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7167-1731

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7167-1731

References

Baláž V., Karasová K. (2017). Geographical Patterns in the Intra-European Migration Before and After Eastern Enlargement: The Connectivity Approach. Economicky Casopis 65(1): 3–30.

Barjaba K., Barjaba J. (2015). Embracing Emigration: The Migration–Development Nexus in Albania. Washington DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Berger J., Mohr J. (1975). A Seventh Man. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Black R., Engbersen G., Okólski M., Pantiru C. (eds) (2010). A Continent Moving West? EU Enlargement and Labour Migration from Central and Eastern Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Blotevogel H. H., Fielding A. J. (eds) (1997). People, Jobs and Mobility in the New Europe. Chichester: Wiley.

Blotevogel H. H., King R. (1996). European Economic Restructuring: Demographic Responses and Feedbacks. European Urban and Regional Studies 3(2): 133–159.

Bonifazi C. (2008). Evolution of Regional Patterns of International Migration in Europe, in: C. Bonifazi, M. Okólski, J. Schoorl, P. Simon (eds), International Migration in Europe: New Trends and New Methods of Analysis, pp. 107–128. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Bonifazi C., Okólski M., Schoorl J., Simon P. (eds) (2008). International Migration in Europe: New Trends and New Methods of Analysis. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Boswell C., Geddes A. (2011). Migration and Mobility in the European Union. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Castles S., Booth H., Wallace T. (1984). Here for Good: Western Europe’s New Ethnic Minorities. London: Pluto Press.

Castles S., de Haas H., Miller M. J. (2014). The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World (5th edition). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Castles S., Kosack G. (1973). Immigrant Workers and Class Structure in Western Europe. London: Oxford University Press and the Institute of Race Relations.

Castles S., Miller M. J. (1993). The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Chesnais J.-C. (1986). La Transition Démographique : Étapes, Formes, Implications Économiques. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Cohen R. (ed.) (1995). The Cambridge Survey of World Migration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Collinson S. (1995). Europe and International Migration (2nd edition). London: Pinter.

Crawley H., Duvell F., Jones K., McMahon S., Sigona N. (2018). Unravelling Europe’s ‘Migration Crisis’. Bristol: Policy Press.

CSO (2014). Polska w Unii Europejskiej 2004–2014. Warsaw: Central Statistical Office.

Eurostat (2011). Demography Report 2010: Older, More Numerous and Diverse Europeans. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurostat (2016). Statistics Explained. Online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_an... (accessed: 15 September 2018).

Fassmann H., Münz R. (1992). Patterns and Trends in International Migration in Western Europe. Population and Development Review 18(3): 457–480.

Fassmann H., Münz R. (1995). European East-West Migration, 1945–1992, in: R. Cohen (ed.), The Cambridge Survey of World Migration, pp. 470–480. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Favell A. (2008). Eurostars and Eurocities: Free Movement and Mobility in an Integrating Europe. Oxford: Blackwell.

Favell A. (2014). The Fourth Freedom: Theories of Migration and Mobilities in a ‘Neoliberal’ Europe. European Journal of Social Theory 17(3): 275–289.

Fihel A., Janicka A., Kaczmarczyk P., Nestorowicz J. (2015). Free Movement of Workers and Transitional Arrangements: Lessons from the 2004 and 2007 Enlargements. Unpublished report to the European Commission. Warsaw: Centre for Migration Studies.

Frey M., Mammey U. (1996). Impact of Migration in the Receiving Countries: Germany. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Garcés-Mascareñas B., Penninx R. (eds) (2016). Integration Processes and Policies in Europe: Contexts, Levels and Actors. Cham: Springer Open.

Giannakouris K. (2008). Ageing Characterises the Demographic Perspectives of the European Societies. Eurostat Statistics in Focus 72/2008: 1–12.

Glorius B., Grabowska-Lusinska I., Kuvik A. (eds) (2013). Mobility in Transition: Migration Patterns After EU Enlargement. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Harris N. (1995). The New Untouchables. Immigration and the New World Worker. London, New York: I.B. Tauris.

IOM (2018). World Migration Report 2018. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Kahanec M., Zimmermann K. (eds) (2016). Labor Migration, EU Enlargement and the Great Recession. Berlin: Springer.

Kemper F.-J. (1993). New Trends in Mass Migration in Germany, in: R. King (ed.), Mass Migration in Europe: The Legacy and the Future, pp. 257–274. London: Belhaven.

King R. (1993a). European International Migration: A Statistical and Geographical Overview, in: R. King (ed.), Mass Migration in Europe: The Legacy and the Future, pp. 19–39. London: Belhaven.

King R. (ed.) (1993b). Mass Migration in Europe: The Legacy and the Future. London: Belhaven.

King R. (ed.) (1993c). The New Geography of European Migrations. London: Belhaven.

King R. (1993d). Why Do People Migrate? The Geography of Departure, in: R. King (ed.), The New Geography of European Migrations, pp. 17–46. London: Belhaven.

King R. (1996). Migration in a World Historical Perspective, in: J. van den Broeck (ed.), The Economics of Labour Migration, pp. 7–75. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

King R. (1997). Restructuring and Socio-Spatial Mobility in Europe: The Role of International Migrants, in: H. H. Bloteveogel, A. J. Fielding (eds), People, Jobs and Mobility in the New Europe, pp. 91–119. Chichester: Wiley.

King R. (2000). Southern Europe in the Changing Global Map of Migration, in: R. King, G. Lazaridis, C. Tsardanidis (eds), Eldorado or Fortress? Migration in Southern Europe, pp. 3–26. London: Macmillan.

King R. (2002). Towards a New Map of European Migration. International Journal of Population Geography 8(2): 89–106.

King R., Black R. (eds) (1997). Southern Europe and the New Immigrations. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

King R., Konjhodzic I. (1996). Labour, Employment and Migration in Southern Europe, in: J. van Oudenaren (ed.), Employment, Economic Development and Migration in Southern Europe and the Maghreb, pp. 7–106. Santa Monica CA: Rand.

King R., Lazaridis G., Tsardanidis C. (eds) (2000). Eldorado or Fortress? Migration in Southern Europe. London: Macmillan.

King R., Lulle A. (2016). Research on Migration: Facing Realities and Maximising Opportunities. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

King R., Vullnetari J. (2012). A Population on the Move: Migration and Gender Relations in Albania. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 5(2): 207–220.

Kosiński L. (1970). The Population of Europe. London: Longman.