The Motivations and Reality of Return Migration to Armenia

-

Author(s):Macková, LucieHarmáček, JaromírPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2019, pp. 145-160DOI: 10.17467/ceemr.2019.09Received:

5 April 2019

Accepted:10 October 2019

Published:9 December 2019

Views: 23623

Return migration has been increasingly gaining prominence in migration research as well as in migration policies across the world. However, in some regions, such as the Caucasus, the phenomenon of return migration is little explored despite its significance for the region. Based on 64 interviews with returnees and key informants together with additional online surveys with Armenian migrants, this study discusses important issues about return and reintegration with policy implications. It covers voluntary returnees as well as the participants of the assisted voluntary return and reintegration programmes and presents the case for a multiplicity of the return migration motivations and experiences which are dependent on the return preparedness and the strategies which the returnees use.

Introduction

Armenia is a country with a large diaspora, estimated at 8 million, compared to the 3 million population residing within the country (Migration Policy Centre 2013). The classic Armenian diaspora was largely created after the 1915 Armenian Genocide, when Armenians were escaping violence in the Ottoman Empire (Safrastyan 2011). Some Armenians also migrated during the turbulent years following the dissolution of the Soviet Union (Makaryan 2012). Armenia is an understudied country with large migration flows. In countries with a significant amount of outmigration, such as Armenia, any return migration is important because it raises significant implications for the region. According to an official from the Armenian Ministry of Diaspora, there have been around 65 000 returnees to Armenia since the early 1990s although only 35 000 of them ultimately remained (personal communication, 6 July 2016).

The priority of return in migration policies in Armenia is not only highlighted by the existence of numerous programmes supporting the phenomenon but also by official Republic of Armenia legal documents – such as the state strategy for migration policy for the years 2017–2021 which features, as one of its top goals, support for the return of Armenia’s citizens, their further reintegration and their possible future involvement in the economic development of the country (State Migration Services 2017). However, the statistics on Armenian migration primarily deal with labour migration to Russia, which is of the highest significance to the region but is outside the scope of this paper.

Return migration can be defined as ‘the process of people returning to their country or place of origin after a significant period of time in another country or region’ (King 2000: 8). The International Organisation for Migration (IOM 2011: 56) specifies the timeframe for return migration, which can be considered as happening ‘usually after spending at least one year in another country’. Reintegration is migrants’ adaptation to society in the country of origin, which can be a difficult task because it would be unreasonable to expect that, during the prolonged period of absence, nothing would change in the country of origin (Arowolo 2000). Reintegration is defined as ‘the process through which a return migrant participates in the social, cultural, economic, and political life of the country of origin’ (Cassarino 2008: 127). The IOM distinguishes four dimensions of reintegration – the social, the cultural, the economic and the psychosocial (IOM 2015).

A combination of individual and structural factors has been found to influence reintegration and the sustainability of return (Black and Gent 2006). Sustainable return can mean the absence of re-emigration but there are also other factors affecting returnees’ long-term socio-economic well-being, such as access to income, shelter, healthcare, education and other services (Black and Gent 2006). The broad definition of sustainability involves both the reintegration of individual returnees and also the wider impact of return on macroeconomic and political indicators. Koser and Kuschminder (2015) focus on returnees’ own perceptions and feelings regarding their well-being and safety in their country of origin. They found that many of the factors influencing the sustainability of return – such as family relations – are outside the scope of direct policy intervention. However, it might still be useful to examine them in order to understand their dynamics.

We can distinguish different types of return on a scale varying between voluntary and forced with voluntary return being the preferred mode. The widest definition that can be used for voluntary return is the absence of force (Black, Koser, Munk, Atfield, D’Onofrio and Tiemoko 2004: 6). If the return is forced or semi-voluntary (Sinatti and Horst 2015), it is harder for the returnees to integrate fully because some of their migration objectives, such as saving money, might not have been accomplished. Returnees who took part in AVRR (assisted voluntary return and reintegration) programmes form a specific group. There have already been several studies on returnees in Armenia (Johansson 2008; Lietaert, Derluyn and Broekaert 2016; Pawlowska 2017). Lietaert et al. (2016) found that returnees who took part in AVRR programmes attached great symbolic importance to their transnational ties, even though they were rarely able to partake in the transnational field. Pawlowska (2017) focused on the ethnic return of Armenian Americans and found that this specific group were disillusioned by their repatriation to Armenia and maintained a symbolic boundary between themselves and the local population. Therefore, returnee groups are not homogenous and any previous experience before returning strongly influences their post-return experience. There is also some policy literature which usually covers short-term labour migration to Russia but only deals with return migration to a limited extent (Agadjanian and Sevoyan 2014).

This paper looks at return migration to Armenia, with the purpose of capturing those factors of return and reintegration which can further contribute to the development of the country of origin. Based on interviews with returnees and key informants, as well as on surveys with Armenian migrants, our research questions are:

- What are the return motivations for Armenian migrants and returnees?

- What are the factors negatively and positively affecting reintegration in Armenia for voluntary and forced migrants?

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. The next section describes the theoretical framework for return migration and development. Then we present the methodology and data for this study and its results before, finally, concluding with a discussion of the possibilities for sustainable return.

Return migration and its impact on development

Cassarino (2004) asserts that, due to the diversity of migratory categories, there is a need to distinguish between the different types of returnee. The distinction can be based on their previous countries of settlement and their individual characteristics (such as skill levels measured by the levels of education). Returnees coming from varying locations face different possibilities and hardships when returning despite sharing the identity of ‘returning residents’ (Horst 2007). Kuschminder (2017) asserts that differences in personal characteristics and between the countries from which returnees come back can affect the overall return outcomes. Furthermore, return is not only a personal issue but also a contextual one, affected by structural factors (Cassarino 2004). The structural barriers can affect returnees across all skill levels. Black et al. (2004) also argue that there are both individual and structural factors influencing the return. While structural factors include the conditions in the country of origin and in the host country, individual factors reflect the migrants’ personal attributes (such as gender or old age) and social relations. The model also works with policy interventions (incentives and disincentives to migrate). Chobanyan (2013) discusses both push and pull factors in the return migration of Armenians, including worsening conditions in the receiving country, xenophobia, homesickness and a desire to raise children in the home country.

A discussion of the reintegration of returnees and its impact on development requires an understanding of the broader context of migration and development – in other words, the migration–development nexus (Faist 2008; Skeldon 2011). Development can occur on the micro and macro scales, taking into account the improving skill levels of individual migrants or, if the number of migrants is sufficiently high, the possible effects on the development of the country of origin. Some governments or international organisations have seen migrants as ‘agents of change’ (Faist 2008) or ‘heroes of development’ (Rodriguez 2002) and, over the years, the global discourse on migration and development has oscillated between pessimism and optimism (de Haas 2010). Let us take remittances that are closely connected with both migration and development as an example. While many hailed these financial flows as the new ‘development mantra’ in the early 2000s (Kapur 2005), others were more sceptical and claimed that there has not been conclusive evidence that remittances promote macroeconomic growth (Yang 2011). However, many consider them to be one of the main benefits of migration for development – for example, as an efficient tool for poverty reduction on the household level (Adams and Page 2005).

According to Radu and Straubhaar (2012), the impact of return migration depends on the magnitude of the migration flows and the selection of migrants. There are different ways in which returnees can contribute to development in the country of origin. Their potential contributions can be subdivided into the occupational choices of the return migrants or, more specifically, returnee entrepreneurship (Dustmann and Kirchkamp 2002; Wahba and Zenou 2012). However, some development scholars criticise the fact that the link between return migration and development is often taken for granted and not critically interrogated (van Houte and Davids 2008). There is a need to explore the barriers to reintegration which can prevent returnees from meaningful engagement linked to development. Returnees who benefit from so-called assisted voluntary return and reintegration programmes (AVRR) often struggle with the return that is not entirely voluntary and with their reintegration. In addition, many returnees report different levels of coercion to encourage them to take part in these programmes (Lietaert et al. 2016). It has been argued that IOM employees are aware of this tension (Koch 2014).

Cassarino (2004) argues that return motivations have two components – the level of their willingness to return and their preparedness. Even if migrants express the wish to move, it does not necessarily mean that they are ready for that move – they might not have enough tangible and intangible resources for the return. In addition, an early repatriation can have an adverse effect on returnees because they might not recover the resources that they had invested in their journey. Moreover, these returnees might not have enough experience from the country of settlement to be able to use it in the form of social remittances (Levitt and Lamba-Nieves 2011) or when starting a new business. On the other hand, returnees who spend longer outside their country of origin might face difficulties due to the changes that occurred in the origin country and to cultural or structural barriers. Therefore, having built on the existing body of literature, we decided to investigate the factors that are important for the sustainable return of Armenians. We inquired about the factors influencing the return decision (i.e. the motivation to return) and the factors affecting returnee reintegration (both positively and negatively), which are also connected to the occupational choices of the returnees.

Methods

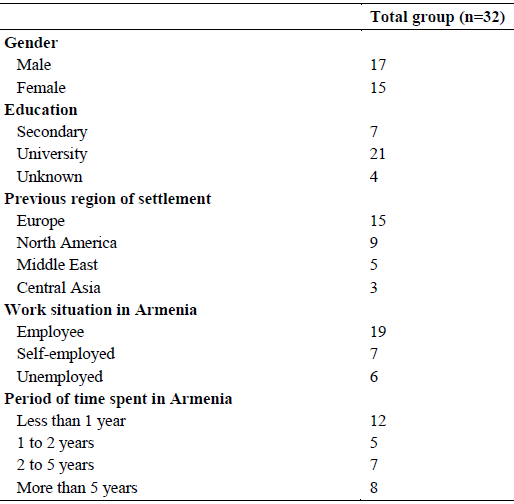

This research combines semi-structured interviews (i) with returnees and (ii) with international migration experts residing in Armenia, with (iii) an online survey with migrants of Armenian origin. The fieldwork in Yerevan and the interviews took place between July and September 2016 and in January 2018, while the online survey was carried out between January and March 2017. The semi-structured interviews with the returnees revolved around the issue of return and reintegration. To have a balanced sample representing different views, an effort was made to recruit people from diverse groups of return migrants (highly skilled vs other skill levels, returning from various countries, assisted, or not, by an organisation during the process of return). In total, there were eight returnees in the sample who were participants in the AVRR programmes. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. First, open coding was used to come up with new ideas and, second, axial coding connected to the text emerged. After the interviews, coding was used to analyse the data. In total, there were 32 returnee interviewees (17 males, 15 females). Of them, 21 had higher education and seven had finished secondary school. All the returnees had lived abroad for at least one year within the last decade but many of them lived abroad for longer periods of time. The return migrants who were interviewed returned from Europe (Germany – 4, Belgium – 4, Hungary and France – 2, Ukraine, Slovakia and Austria – 1), North America (USA – 6, Canada – 3), the Middle East (Syria, Lebanon, Iran, Qatar, Egypt, 1 each), Russia (2), and Georgia (1). In total, 19 returnees were employed, seven were self-employed and six unemployed. They spent different periods of time in Armenia: 12 of them less than a year, five of them one to two years, seven of them two to five years and eight more than five years (see Table 1).

Additional data were drawn from the interviews with the 32 key informants – all experts on international migration in Armenia. The interviews were semi-structured and were conducted around the key theme of return migration, with the aim of grasping the complexity of the phenomenon and eliciting answers to the research questions. All interviews were recorded, transcribed and subsequently analysed using qualitative coding. Most of the key informant interviews took place in Yerevan because the vast majority of organisations dealing with migration, state agencies, NGOs, international organisations such as United Nations agencies and of academic institutions have their seats in the capital. The key informants were selected from a list of organisations working on the issue of migration in Armenia and their selection was made following consultation with other key informants and researchers working in the country.

A combination of snowball sampling and personal and organisational networks was used to engage further interviewees. Many of the interviewees were active in the policy field and worked actively with the State Migration Services – the key migration actor in Armenia. The interviews revolved around the themes of return migration and reintegration, development in Armenia and potential barriers to returnee reintegration. Some of the interviewees were returnees themselves. The expert interviews are seen as ‘crystallisation points’ for insider knowledge and also serve as an entry point to the field of research (Bogner, Littig and Menz 2009: 2). This type of data generation is not unproblematic but it serves the purpose of eliciting ideas that can be applied to a broader range of people.

Table 1. Overview of the interviewed returnees

Another method used was a survey aimed at Armenians living outside Armenia. An online survey was launched on the SurveyMonkey platform from January to March 2017. The survey included a total of 25 questions divided into two categories – demographic data and the possibility of a return to Armenia. The questionnaire was mixed – i.e. it included both closed and open-ended questions. To disseminate the survey widely among Armenians outside Armenia, networking websites such as Facebook and LinkedIn were used. The link to the survey was posted on various groups for diaspora Armenians on Facebook (e.g. Armenians in Germany, France, the Czech Republic and Slovakia). Personal and institutional networks were also used to disseminate the survey.

In total, there were 146 respondents in the survey, 93 (64 per cent) of them female and 52 (36 per cent) male. They came from a wide range of countries, including the USA (11 per cent), France (9) and Russia (4). There were 28 respondents from the Czech Republic (19 per cent) which was also due to the channels through which information about the survey was disseminated. Other respondents lived in China, Poland, Germany, Turkey, Canada, Hungary or Slovakia. More than half of the respondents (51 per cent) were in the age group 21–29 years. The second most represented age group was made up of Armenian migrants aged 30–39 (29 per cent), followed by those aged 40–49 (7 per cent) and 18–20 (6 per cent). Compared to the overall population of Armenian migrants living abroad, younger and more educated respondents answered the survey questions. In total, 62 per cent of the respondents had a graduate degree, while 18 per cent had a BA and 11 per cent a high-school qualification. The marital status of the respondents also reflected this younger age bias, with 59 per cent being single and 30 per cent married. The majority of the respondents (74 per cent) had no children.

Almost half of the sample (48 per cent) stayed abroad for more than five years. The second most frequent period of stay was between one and three years (24 per cent); 15 per cent of migrants stayed less than one year and 13 per cent between three and five years. Finally, the respondents were mainly employed (44 per cent) or students (39 per cent). Some were unemployed and looking for work (4 per cent), while those who were not in employment and not looking for work numbered 3 per cent, as did retired migrants. There can be several limitations with this type of survey, mainly because it is self-selected. Another limitation was the online form, which was not accessible to everyone. The third barrier was the English language. However, designed as it was, it shed light on a relatively little-researched group of Armenian migrants – those who speak English, have professional jobs or are students. Moreover, in Armenia, seasonal migration to Russia and the effects of remittances from this country are relatively well researched (Agadjanian and Sevoyan 2014; Grigorian and Melkonyan 2011). Therefore, this type of limitation in the surveys may be justified – it allowed us to learn more about the group of potential returnees who could have a high impact on the development of Armenia due to their high skill levels.

Return motivations

The motivation to return represents an important factor for returnee reintegration. While there is a complex array of overlapping motivations encouraging returnees to go back, several of them emerged as important. These motivations and expectations will be discussed in the following section on return motivations. In the next part, we focus on the reality of return, which is a difficult experience for many returnees who struggle with reintegration. We investigate both the negative and positive factors influencing returnee reintegration, both on the individual and on the structural level. We have found that the returnees’ personal characteristics – such as skills, networks and social relations – and their willingness and preparedness to return are necessary for them to be able to reintegrate successfully. However, the wider environment in Armenia, including the economic and other social and structural factors (such as corruption) can affect reintegration in a negative way.

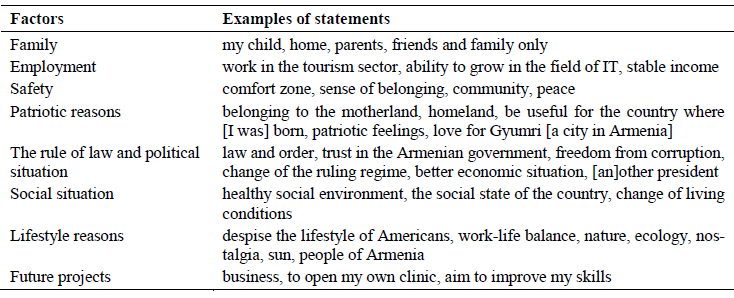

We enquired about the motivations to return in the survey as well as in the interviews. The return motivations are similar for the Armenian migrants residing abroad and the returnees. In both groups, family (being close to relatives and friends) and work-related reasons were mentioned frequently. The themes related to human security, patriotism, and the overall environment in Armenia also appeared in both the surveys and the interviews. In response to the survey, the main reasons cited for the respondents’ return to Armenia were family (n=80), employment (n=33) and safety (n=23). The motivations did not generally differ by gender. However, respondents under the age of 40 gave family reasons as their main motivation for return (n=76), whereas the older respondents (40+) were more motivated to return because of an employment offer (n=6). Among other answers not directly related to the previous options, the migrants mentioned factors such as patriotism, reasons relating to the rule of law, political and social situation, lifestyle or future projects in Armenia (see Table 2).

Table 2. Reasons relating to return among migrants (survey results)

The motivation to return due to relations in Armenia was a general feeling echoed by many migrants across all skill levels. These sentiments are often mixed with patriotic reasons for returning. Some of the survey respondents remarked that they wanted to return because they wanted their children to grow up in Armenia and be close to their grandparents. Similar factors influencing return also appeared in the interviews. One 43-year-old returnee from the US mentioned how important it was for her that her daughter should have ‘full Armenian identity’ and be close to her grandparents. Another woman (54) returning from Germany stated that she went back to Armenia to take care of her elderly mother. When she was in Germany, she did not feel integrated and missed Armenia. This woman was assisted by an NGO within the framework of an AVRR programme. Other assisted returnees mentioned motivations relating to their families but also to the conditions in their previous country of residence and the lack of choice when it came to decision-making about their return.

Motivations connected to patriotism often appeared in the interviews. One 33-year-old returnee from Canada stated that he returned for ‘identitarian and pragmatic reasons’. A 27-year-old returnee from France noted, ‘I liked living in Europe, but I felt it was my neighbour’s home. And I have to create the same effort in my home, meaning my country. I am an Armenian woman. I have to work for some change and help people’. Moreover, the feeling of not belonging being the main impetus for return can also be connected to discrimination in the country of settlement. One female interviewee aged 27, who had returned from Iran, stated that ‘as a member of a minority [she] felt discriminated [against]’. Another interviewee, a 27-year-old man who had come back from Syria, said that the situation in his previous country of residence made you feel that ‘you don’t belong there’.

For many returnees, security was equally important. This relates not only to having a stable job but also to general levels of security in the country. One male returnee (29) from Syria stated, ‘I moved here for the job as well as the security. I had arranged my first job before coming here’. The safe environment and the general levels of security in Armenia were perceived as favourable. One female returnee from the US (43) asserted, ‘There is less stress here; the type of worry is different. For example, in daycare in the US, I had to be aware of strangers and had to teach my child to beware of strangers’.

Many returnees enjoyed the lifestyle in Armenia that was perceived as relaxed and conducive to the life–work balance: ‘Here you have the small city lifestyle. You can walk everywhere. You can sit down and have a coffee without thinking that you’ll be late’ (man, 42, returned from the US).

However, for some of the returnees, Yerevan was seen as quiet and not offering many opportunities. One 28-year-old female returnee complained: ‘First, I hated the slow pace of life here. So slow. In Lebanon, there is this active lifestyle. I had two jobs. I ran from one to the other’.

In the online survey, the migrants rated the opportunities for a good work–life balance compared to other countries. About a third (35.3 per cent) of the respondents thought that Armenia offered few opportunities for a good work–life balance and only 11 per cent thought the contrary.

Another motivation often cited by both the migrants in the survey and the returnees in the interviews is the importance of future projects, as one returnee noted:

Now it is happening that smart people return to Armenia when they have young kids. They see it as a future for the kids. They have some emotional ties with the country. The first people who returned were the revolutionary types who started the movement to the country. Now the new types look for housing, a better quality of life and schools for children. They decide to come here for three years and see how it is. They already come with a job as a CEO or start their own company (male, 45, returned from the US).

Generally, there are multiple reasons for return. However, in case of voluntary returns to Armenia, people usually went back because they had relations in the country or for work-related and patriotic reasons. These returns are generally planned in advance and the returnees can make use of their social networks in Armenia to start new projects. In contrast, as a result of a return that is hasty and not prepared in advance, returnees often struggle with reintegration. This is usually the case during the so-called assisted voluntary returns, during which returnees might have been coerced into leaving the country of settlement. It is apparent that a strong motivation to return is important in preparing for the returnees’ integration (Cassarino 2004). This, in turn, plays a significant role in the success of the reintegration process.

Factors negatively affecting reintegration in Armenia

In this section, we explore the returnees’ experiences after their return to Armenia by investigating the factors that influence the reintegration process. It is important to note that most of these factors can have both positive and negative effects – in other words, they can go either way. The factors affecting reintegration are closely linked to the migrants having enough tangible and intangible resources for the return to their country of origin. The timing of the return also plays a role. An early repatriation can have an adverse effect on returnees because they might not recover the resources that they had invested in their journey. This is generally the case of the AVRR returnees who go back after only a short period of time, usually not exceeding one or two years. Moreover, these returnees might not have enough experience from the country of settlement to be able to use it in the form of social remittances or when starting a new business. Similarly, the intention to return, together with being properly prepared for it, are crucial too. Our aim was to find out which of the factors are perceived quite positively and which are understood as negative in the Armenian context. We first focus on the factors negatively affecting the reintegration process in Armenia before analysing those with positive effects.

We begin this section with a discussion of the Armenian migrants’ perceived concerns about reintegration. We then proceed to the actual experience of the returnees and examine what they see as the factors that negatively affected their return. Finally, the statements by the key informants about the barriers to returnee reintegration will conclude the section. In the online survey, the Armenian migrants mentioned the following barriers, which they feared could have a negative impact on their reintegration. For the clear majority of them (52 per cent), the main issues were employment- and economy-related. Others were concerned about corruption (7 per cent), the government (5 per cent), family (4 per cent) or injustice (3 per cent). Poverty, low salaries and high levels of unemployment create conditions that make people leave in the first place and make it equally difficult for them to return. Despite some improvements over the past two decades, labour-market conditions in Armenia are still problematic (ETF 2013).

Similar concerns were raised by the returnees during the interviews. For those who did not have the opportunity to become self-employed and who lacked the relevant networks, finding employment was often difficult. Even if the returnees found a job, there were other issues that they thought prevented them from reintegrating. These issues mainly revolved around the low levels of salaries and limited opportunities for professional growth, which one 32-year-old female returnee from the US called ‘an inhibition of opportunities’. Others noted that the economic aspects of living in Armenia are challenging. One noted, ‘I’m working for experience now. You didn’t come here to save money’ (woman, 28, returned from Lebanon). Another returnee – a 29-year-old male returned from Syria – mentioned the practical difficulties with making ends meet: ‘The salary in my first job was low and the rents are expensive. This can be difficult for some people’.

However, returnees who had already found a job also mentioned other concerns connected to the social environment in Armenia. One, a 43-year-old female back from the US, mentioned that, in Armenia, ‘older people are not safeguarded’. Returnees were also concerned about government services such as healthcare. For example, the returnees ‘would like to have more services from the government for [the] taxes. There is just basic healthcare’ (female 27, returned from Iran).

The returnees also pointed out some issues connected to the norms in the society that were not comparable with what the returnees experienced while living abroad. They mentioned, for example, the relations between genders or other norms such as smoking indoors. According to this 32-year-old female, returned from the US, ‘There are some things that I find difficult here, some cultural things. Sometimes you are stared at and [I find problematic] the way in which men treat women’. This male returnee from Canada (33) claimed that, ‘There is a lot of ignorance too, for example, about second-hand smoking. So you’re going to live in a safe country but everyone is going to have lung cancer’.

The key informants agreed that, for many returnees, it is difficult to find a job. One of the employees of the Targeted Initiative for Armenia asserts that

the first and the most urgent issue that they face is unemployment. When they come back, they have no economic resources to support the family. These are the reasons why they decided to migrate in the first place (personal communication, 22 July 2016).

Some key informants also stressed that difficulties in reintegrating await everyone, even those highly skilled returnees who have been targeted by the project run by the German Federal Enterprise for International Cooperation (GIZ). One of the employees of GIZ claimed that

moving back to Armenia is not a one-day decision; they should come to this idea gradually. Of course, they can have a lot of barriers in mind. Therefore, our idea was also to present the cases showing how these difficulties can be overcome. If a person wants to return, it is his (sic) decision and he should know beforehand that there will be problems (personal communication, 13 July 2016).

Corruption is yet another problem that is encountered not only when returnees want to avail themselves of the services of the state but also when they try to engage in entrepreneurial activities. This issue is experienced as a problem particularly by returnees from countries with low levels of corruption (Paasche 2016). The state is the most important player when it comes to addressing corruption. Even if some of the returnees stated that the situation in Armenia is better than it was several years ago, it still represents an important problem for Armenian returnees. One man (41) who had returned from Russia claimed that ‘in many countries, corruption is experienced on different levels. Normally it is the task of the government to eliminate petty corruption, but it is not happening in Armenia’.

Transparency International (TI) in Armenia is the main organisation addressing corruption. TI’s current Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) places Armenia 107th out of 180 countries observed. While this index has its limitations, it nevertheless illustrates the stark differences between Armenia and neighbouring Georgia (placed 48th). The following statement comes from a member of the TI staff in Armenia:

Because of corruption we have a small market. People leave the country so there are fewer consumers. People cannot import goods because it is very monopolised because we cannot touch certain areas. If I wanted to start a business importing fuel, I would be asked not to do that. So is the market small or maybe more illegally regularised? (personal communication, 29 July 2016).

To summarise, Armenian migrants, returnees and key informants single-mindedly stressed the importance of income-generating activities for returnees. However, there were also other factors which negatively affected the returnees’ sense of well-being – such as corruption, the social environment and social norms. Beyond these, it has already been stated that the primary motivation to return affects the returnees’ subsequent reintegration in the country of origin. In the case of semi-voluntary or forced returns, it is much harder to reintegrate than in returns where the decision was purely voluntary. If people perceive their return as forced (even in the case of AVRR programmes), reintegration becomes difficult, as illustrated by the following quote from a 61-year-old male returnee from Belgium: ‘I am alone here. It is a torture for me. If I had a safe and legal chance to go back I would go’. This person was separated from his family, who were still in Europe, due to legal reasons and had little time to prepare for his return. This quote came from him in spite of his being assisted by a non-governmental organisation during his return process.

Factors positively affecting reintegration in Armenia

As in the previous section, we begin our analysis with the migrants’ perspectives, then continue with the returnees’ views and key informants’ opinions. As already mentioned, the factors that influence reintegration in Armenia are linked to the resources which can be tangible (such as money) or intangible (such as returnees’ skills, strong personal networks or sense of initiative).

The survey results show that 59 per cent of the respondents thought that their levels of skills and professional knowledge had increased significantly while 32 per cent thought that they had increased to some extent. This is consistent with the returnees’ responses during the interviews, when they were asked about their skill levels. Some stated that there were various skills that they had learnt while living abroad. One 27-year-old female returnee from the US stressed the skills such as flexibility and open-mindedness: ‘I have some skills from the US. For example, the education system taught me flexibility. There are many different things, research skills. I am willing to learn new things’. Another woman aged 43, similarly returned from the US, highlighted better communication: ‘You ask about everyone’s job and you try to do networking. I think that after this experience, I approach people more easily’.

The returnees also stressed a sense of initiative and creativity that was important for their reintegration. ‘I’m really creative now. Before, I used to believe what I was told. Now I have my own ideas and solutions’ (woman, 27, returned from Iran). A 41-year-old male returnee from Russia noted that ‘Everyone wants to open a hairdressing salon, a kebab [stall]. People complain about the taxes, but even if you don’t need to pay taxes but you don’t have any ideas, you’ll fail’. The innovative ideas that are conducive to reintegration were mentioned by returnees and key informants alike. Some organisations try to support innovative ideas and returnees’ involvement. While the UNDP attempts to work in the region, they acknowledge that the most innovative ideas come from the capital. One UNDP staff member argued that ‘These entrepreneurial activities are (…) fighting against this sense of apathy amongst the population which is very high. We try to attract ideas from outside Yerevan, in the regions’ (personal communication, 22 July 2016).

Other returnees stress the sense of entrepreneurism that is seen as crucial for sustainable reintegration. As this male returnee (42) from the US stated: ‘They suffer a lot here if they are not entrepreneurial types. If you are running away from something, for example, if you were not successful, it is not going to work’. Another returnee from the US, a male in his 40s, agrees that ‘there are opportunities for entrepreneurism, you see others who have succeeded then it becomes possible. Economic opportunities are the most important hopes of economic prosperity’.

Another important factor for successful and sustainable return is strong personal networks. Some returnees noted that they felt that their networks supported them in their decision to move back to Armenia.

Here I feel at home. I learned to make this my home. I did not feel like this from the beginning. (…) But the life is real, the issues are real. (…) My family [outside of Armenia] was supportive of my decision to move because they were very attached to Armenia (man, 53, returned from Canada).

The returnees made use of their support networks back in Armenia, especially at the beginning – i.e. right after their return. One female returnee (27) from Iran said that ‘The neighbours are helpful, they cooked food for me. There is a lot of trust because they’re Armenian’.

New social contacts and friends made it easier for returnees to reintegrate.

The social life here is great. It is easy to make friends here. People enjoy their life and there are some things that money can’t buy. In [the previous city of residence] it was hard to connect with people. It was hard to form a genuine connection (woman, 32, returned from the US).

Networking, or being able to capitalise on their social contacts, emerges as an important strategy for a successful returnee experience, needed to secure income generation. As one 25-year-old female returnee from Hungary remarked, ‘Networking is all that we are left with’. Should this fail, returnees depend on the support of non-governmental organisations, support which differs across organisations. Many of them work on the premise that returnee entrepreneurship can be beneficial for the development of Armenia regardless of the skill levels of returnees or their personal characteristics.

Some of the returnees with high levels of skills did not see many obstacles when it came to reintegration or starting a business. As one man (45, returned from the US) noted, ‘In order to start a business, there are no barriers, no differences [but it] is dependent on the sector’. Another skilled returnee from the US, a male aged 42, agreed.

There are no obstacles to people who want to work in Armenia. If you want to start a business, nobody will discriminate against you. There can be problems with culture and language. You have to speak Russian if you want to do business in Armenia but other than that, legally, it is not a problem.

While not all returnees encounter difficulties, it is more common that they occur. Furthermore, the obstacles vary across different groups of returnees; it is possible to conclude that they are less serious for returnees with higher levels of skills. Moreover, there can be some cultural and language difficulties but these are quite rare for first-generation returnees (i.e. those who were born in Armenia).

Organisations supporting returnees are also important for returnee reintegration. Black et al. (2004) argue that one factor that affects the sustainability of return is the availability of programmes for returnees. According to van Houte and Davids (2008), returnees can become disappointed with the support that they receive from non-governmental and international organisations because of the unrealistic expectations which they, the returnees, create. There are different support programmes for returnees in Armenia, ranging from the provision of support for skilled returnees (e.g. Repat Armenia and Birthright Armenia) to AVRR schemes run by IOM as well as by some NGOs. However, this is often short-term support. A member of staff from the ICMPD warned that ‘the economic growth cannot come from reintegration programmes. This type of assistance is not really sustainable [as] it is a temporary measure’ (personal communication, 25 July 2016).

Returnees who had been assisted by an organisation with their return often complained that the levels of assistance were low. The same view was held by the experts, who asserted that the financial assistance that returnees receive might not be enough to start up a business. While returnee entrepreneurship represents quite a productive activity, it should not be taken as a replacement for access to the labour market. Moreover, the assistance of some organisations is often provided in a form of a loan that has to be paid back. While the returnees might not have a choice as to whether to become entrepreneurial or not (due to a lack of other employment opportunities), they must still repay the loans which they were granted.

Returnees and the organisations working with them usually stress the importance of returnees’ own initiative and sense of entrepreneurship. However, not all returnees have the required personal characteristics to become entrepreneurs and this should be taken into consideration when devising programmes for them. Another sensitive issue is that the support given to returnees has to be well-thought out. One of the employees from the OSCE office in Yerevan stated the following:

We have to be careful with the returnees because in some situations, the neighbours who never left are often worse off and they don’t get any attention. This creates social tensions, an increase of dissatisfaction and frustration (personal communication, 26 July 2016).

Conclusion

Our paper has dealt with the motivations and the reality of return migration to Armenia. We have covered two broad but closely related areas – the motivations to return and the factors that affect the reintegration process in Armenia. We found that the motivations for return are largely connected not only to personal networks but also to the overall social and economic situation in Armenia, which is still perceived as problematic by some of the migrants and returnees. As for the factors affecting reintegration, we have identified a combination of individual and structural factors which can influence it. While we consider our results to be informative, we also admit that they cannot be generalised and applied to other countries or regions due to the small sample of respondents.

The results have shown that both return motivation and the returnees’ preparedness for it affect the overall return experience and the sustainability of reintegration. The returnees who are motivated and prepared to return are often in a better position compared to returnees who may have been assisted by an AVRR programme. Particularly when the return is subjectively perceived as forced, it is difficult for the returnees to reintegrate. In contrast, voluntary and well-planned returns significantly increase the chances of successful reintegration. This suggests that our study confirms the link between the motivation to return and the subsequent subjective perception of reintegration which has already been established in the literature (Cassarino 2004). However, the strength of such a link, as well as the influence of various factors affecting returnee reintegration, are dependent on the individual characteristics of the returnees. To create effective policies on return and reintegration, it is crucial to know who the returnees are and what needs they have.

It seems that, in the case of Armenia, the previous country of settlement itself is not that significant in returnee reintegration. This study covers a large sample of previous countries of settlement but there were no obvious similarities among the returnees coming from the same countries. However, what mattered was the type of migration experience and the returnees’ skill levels and social capital, some of which were acquired in the previous country of residence. While some returnees return because of the economic situation in the receiving countries (Buján 2015), this was generally not the case among the interviewed Armenian returnees. The structural barriers to reintegration – such as high levels of unemployment and difficulties in obtaining a job – related particularly to the labour-market conditions in Armenia. The returnees with higher levels of skills and work experience from abroad might have a comparative advantage vis-à-vis resident Armenians and usually obtained a job despite some initial difficulties. Our findings are in line with other studies on return migrant transnationalism, which show that migrant transnationalism and integration might not be competing forces (Carling and Pettersen 2014). Return migration can also be the outcome of successful integration in receiving societies (de Haas and Fokkema 2011) or at very least, successful integration might not significantly affect return intentions (de Haas, Fokkema and Fihri 2014).

The duration of the stay abroad also influences the return migration outcomes. Returnees who only stayed abroad for a short time (such as returnees assisted by AVRR programmes) might not have enough experience from the country of settlement to be able to use it in the form of social remittances or when starting a new business. During the study, the expert opinions largely mirrored the views of the returnees themselves. However, there were some exceptions – for example, the issue of corruption as one of the barriers to reintegration was stressed more by the key informants than by the returnees. Compared to the study by Paasche (2016), Armenian returnees did not perceive corruption as the major obstacle to their reintegration. Many returnees also perceived the differences in the social and gender norms in the Armenian society compared to their previous country of residence. However, this is quite common among the return migrants (Christou 2006).

In all cases, reintegration should be seen as crucial to a meaningful engagement in the country of origin. This issue is also connected with the social remittances that the returnees continue to exert in their country of origin and which can have positive impacts on the social norms (Levitt 1998; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves 2011). Therefore, it is important to critically investigate this link between reintegration and development because it will allow analysts, policy-makers and the different organisations working with returnees to devise policies and programmes not only to improve the return experience but also to enhance the positive effects on development in the country of origin. However, return migration is understood and interpreted differently by policymakers and migrants targeted by the policies (Sinatti 2015). While the AVRR programmes are largely skewed in favour of the donor countries (largely in Western Europe), their outcomes are rarely investigated. Therefore, more emphasis needs to be put on evidence-based policies and those practices which work well. This study serves as a stepping-stone to this debate by comparing different reintegration outcomes based on return motivations, incorporating the experience before return and the post-return barriers.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID ID

Lucie Macková  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1077-7476

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1077-7476

Jaromír Harmáček  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3711-0663

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3711-0663

References

Adams R., Page J. (2005). Do International Migration and Remittances Reduce Poverty in Developing Countries? World Development 33(10): 1645–1669.

Agadjanian V., Sevoyan A. (2014). Embedding or Uprooting? The Effects of International Labor Migration on Rural Households in Armenia. International Migration 52(5): 29–46.

Arowolo O. O. (2000). Return Migration and the Problem of Reintegration. International Migration 38(5): 59–82.

Black R., Gent S. (2006). Sustainable Return in Post-Conflict Contexts. International Migration 44(3): 15–38.

Black R., Koser K., Munk K., Atfield G., D’Onofrio L., Tiemoko R. (2004). Understanding Voluntary Return. Technical Report. London: Home Office.

Bogner A., Littig B., Menz W. (2009). Interviewing Experts. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Buján R. M. (2015). Gendered Motivations for Return Migrations to Bolivia from Spain. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 13(4): 401–418.

Carling J., Pettersen S. V. (2014). Return Migration Intentions in the Integration–Transnationalism Matrix. International Migration 52(6): 13–30.

Cassarino J.-P. (2004). Theorising Return Migration: The Conceptual Approach to Return Migrants Revisited. International Journal on Multicultural Societies 6(2): 253–279.

Cassarino J.-P. (ed.) (2008). Return Migrants to the Maghreb, Reintegration and Development Challenges. San Domenico di Fiesole: European University Institute (EUI), Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies.

Chobanyan H. (2013). Return Migration and Reintegration Issues: Armenia. CARIM-East Research Report, EUI RSCAS 2013/03. San Domenico di Fiesole: European University Institute.

Christou A. (2006). Crossing Boundaries – Ethnicizing Employment – Gendering Labor: Gender, Ethnicity and Social Networks in Return Migration. Social & Cultural Geography 7(1): 87–102.

de Haas H. (2010). Migration and Development: A Theoretical Perspective. International Migration Review 44(1): 227–264.

de Haas H., Fokkema T. (2011). The Effects of Integration and Transnational Ties on International Return Migration Intentions. Demographic Research 25: 755–782.

de Haas H., Fokkema T., Fihri M. F. (2015). Return Migration as Failure or Success? Journal of International Migration and Integration 16(2): 415–429.

Dustmann C., Kirchkamp O. (2002). The Optimal Migration Duration and Activity Choice after Re-migration. Journal of Development Economics 67(2): 351–372.

ETF (2013). Migration and Skills in Armenia. Yerevan: European Training Foundation.

Faist T. (2008). Migrants as Transnational Development Agents: An Inquiry into the Newest Round of the Migration–Development Nexus. Population, Space and Place 14(1): 21–42.

Grigorian D., Melkonyan T. A. (2011). Destined to Receive: The Impact of Remittances on Household Decisions in Armenia. Review of Development Economics 15(1): 139–153.

Horst H. A. (2007). You Can’t Be Two Places at Once: Rethinking Transnationalism Through Jamaican Return Migration. Identities 14(1–2): 63–83.

IOM (2011). International Migration Law. Glossary on Migration. Online: http://www.iomvienna.at/sites/default/files/IML_1_EN.pdf (accessed: 14 November 2019).

IOM (2015). Reintegration Effective Approaches. Geneva: International Organisation for Migration.

Johansson A. (2008). Return Migration to Armenia: Monitoring the Embeddedness of Returnees. Nijmegen: AMidSt-CIDIN.

Kapur D. (2005). Remittances: The New Development Mantra, in: S. M. Maimbo, D. Ratha (eds), Remittances: Development Impact and Future Prospects, pp. 331–360. Washington: World Bank.

King R. (2000). Generalizations from the History of Return Migration, in: B. Ghosh (ed.), Return Migration: Journey of Hope or Despair?, pp. 7–55. Geneva: International Organisation for Migration.

Koch A. (2014). The Politics and Discourse of Migrant Return: The Role of UNHCR and IOM in the Governance of Return. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40(6): 905–923.

Koser K., Kuschminder K. (2015). Comparative Research on the Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration of Migrants. Geneva: International Organisation for Migration.

Kuschminder K. (2017). Taking Stock of Assisted Voluntary Return from Europe: Decision Making, Reintegration and Sustainable Return – Time for a Paradigm Shift. San Domenico di Fiesole: European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies.

Levitt P. (1998). Social Remittances: Migration-Driven Local-Level Forms of Cultural Diffusion. International Migration Review 32(4): 926–948.

Levitt P., Lamba-Nieves D. (2011). Social Remittances Revisited. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 37(1): 1–22.

Lietaert I., Derluyn I., Broekaert E. (2016). The Boundaries of Transnationalism: The Case of Assisted Voluntary Return Migrants. Global Networks 17(3): 366–381.

Makaryan S. (2012). Estimation of International Migration in Post-Soviet Republics. International Migration 53(5): 26–46.

Migration Policy Centre (2013). MPC Migration Profile Armenia. Online: http://www.migrationpolicycentre.eu/docs/migration_profiles/Armenia.pdf (accessed: 15 November 2019).

Paasche E. (2016). The Role of Corruption in Reintegration: Experiences of Iraqi Kurds upon Return from Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42(7): 1076–1093.

Pawlowska K. (2017). Ethnic Return of Armenian Americans: Perspectives. Anthropological Notebooks 23(1): 93–109.

Radu D., Straubhaar T. (2012). Beyond ‘Push–Pull’: The Economic Approach to Modelling Migration, in: M. Martiniello, J. Rath (eds), An Introduction to International Migration Studies, pp. 25–56. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Rodriguez R. M. (2002). Migrant Heroes: Nationalism, Citizenship and the Politics of Filipino Migrant Labor. Citizenship Studies 6(3): 341–356.

Safrastyan R. (2011). Ottoman Empire. The Genesis of the Program of Genocide (1876–1920). Yerevan: Zangak.

Sinatti G. (2015). Return Migration as a Win-Win-Win Scenario? Visions of Return among Senegalese Migrants, the State of Origin and Receiving Countries. Ethnic and Racial Studies 38(2): 275–291.

Sinatti G., Horst J. (2015). Migrants as Agents of Development: Diaspora Engagement Discourse and Practice in Europe. Ethnicities 15(1): 134–152.

Skeldon R. (2011). Reinterpreting Migration and Development, in: N. Phillips (ed.), Migration in the Global Political Economy. International Political Economy Yearbook, pp. 103–119. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

State Migration Services (2017). 2017–2021 Strategy for Migration Policy of the Republic of Armenia. Online: http://smsmta.am/upload/Migration_Strategy_2017-2021_english.pdf (accessed: 15 November 2019).

van Houte M., Davids T. (2008). Development and Return Migration: From Policy Panacea to Migrant Perspective Sustainability. Third World Quarterly 29(7): 1411–1429.

Wahba J., Zenou Y. (2012). Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Migration, Entrepreneurship and Social Capital. Regional Science and Urban Economics 42(5): 890–903.

Yang D. (2011). Migrant Remittances. Journal of Economic Perspectives 25(3): 129–152.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.