Push, Pull and Brexit: Polish Migrants’ Perceptions of Factors Discouraging them from Staying in the UK

-

Author(s):Jancewicz, BarbaraKloc-Nowak, WeronikaPszczółkowska, DominikaPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2020, pp. 101-123DOI: 10.17467/ceemr.2020.09Received:

31 October 2019

Accepted:25 May 2020

Views: 12494

The fate of European citizens living in the United Kingdom was a key issue linked with Britain’s departure from the European Union. Official statistics show that some outflow has taken place, but it was no Brexodus. This article investigates Brexit’s impact within a theoretical (push–pull) framework using a survey of long-term Polish migrants in the UK (CAPI, N = 472, conducted in 2018). Our results show that the perception of Brexit as a factor discouraging migrants from staying in the UK was limited. Still, those with experience of living in other countries, those remitting to Poland, and those on welfare benefits, were more likely to find Brexit discouraging. However, many claimed that the referendum nudged them towards extending their stay instead of shortening it. In general, when asked about what encourages/discourages them from staying in the UK, the respondents mainly chose factors related to the job market. Therefore, we argue, in line with Kilkey and Ryan (2020), that the referendum was an unsettling event – but, considering the strong economic incentives for Polish migrants to stay in the UK, we can expect Brexit to have a limited influence on any further outflows of migrants, as long as Britain’s economic situation does not deteriorate.

Introduction

The results of the British referendum of June 2016, with the majority of voters supporting the proposal to leave the European Union, caused very emotional reactions among many of the 3.7 million citizens of other EU countries residing in the United Kingdom (Brahic and Lallement 2020; Guma and Dafydd Jones 2019; Lulle, Moroşanu and King 2018). Immediately, researchers (McGhee, Moret and Vlachantoni 2017; Piętka-Nykaza and McGhee 2017) started working to predict how the perception and possible consequences of Brexit would influence the intentions and life strategies of migrants, including the over 1 million Polish citizens – the largest group of European immigrants in the UK. Even before the new legal conditions of residence for foreigners were known, some scholars predicted an outflow of people (Portes 2016; Portes and Forte 2017), while others believed it would have a limited effect (McGhee et al. 2017). We argue, in line with Kilkey and Ryan (2020), that the referendum was an unsettling event but, by itself, will not be enough to cause a major outflow of migrants. We believe that post-Brexit migration is still in line with pre-Brexit studies and theories on intra-EU mobility, where economic factors – such as available employment, high earnings and career development – were key forces behind migrants’ decisions.

Brexit, and especially its impact on migration, is an occasion to understand better how people decide to migrate, stay or return and how they relate to their countries of origin and residence. In order to achieve this, we present the results from a face-to-face survey (N = 472) of long-term Polish migrants in the UK, conducted two years after the referendum but still before the UK left the EU. Our analysis follows the wider push–pull framework (Lee 1966) to determine whether the individuals’ perceptions of various factors encouraged them to remain or discouraged them from staying in the UK. The changes brought about by Brexit had a varying impact on migrants depending on their individual characteristics and situation. Thus we test not only whether Brexit was a factor discouraging some migrants from staying in the UK but also who these discouraged migrants were and how this related to their socio-economic, legal, cultural or political integration (Entzinger and Biezeveld 2003).

Our article contributes to the literature by investigating Brexit’s impact in the context of a larger set of factors and analysing it within a theoretical (push–pull) framework. Our study shows how political shifts, such as the Brexit referendum and the following process, were reflected in different migrants’ perceptions, which might in turn influence migrants’ decisions. The article starts with a short overview of the trends in Polish migration and naturalisation statistics in the period leading to and following the Brexit referendum. The subsequent sections set the conceptual basis for our analysis by first referring to the literature on post-EU accession migrants and the strategies and factors affecting their decisions regarding their stay in the UK and then moving on to the more general push/pull framework in which our hypotheses are grounded. After presenting our methodology and data, we turn to the analysis and discussion of the survey results – descriptive statistics and logistic regression – which lead to our conclusions.

State of knowledge regarding Brexit

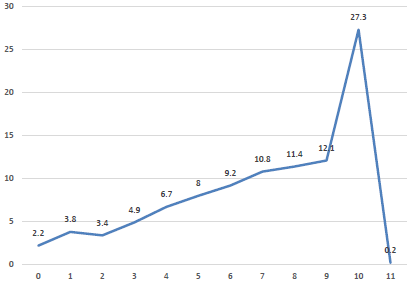

Official statistics for 2017 and 2018 (ONS 2019) have demonstrated that net migration from the EU has decreased significantly since the referendum and that net migration from the EU8 countries (those which joined the Union in 2004, including Poland) has even become negative. In the case of Polish migrants, between 2005 and 2016 the number of Polish citizens moving to the UK was constantly larger than the number of those leaving, with both numbers being almost equal only in 2008, the year when the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) started, when outflows increased somewhat and inflows decreased significantly; 2017 was the first year since EU enlargement when slightly more Polish people left the UK than arrived, again due to higher outflows and especially lower inflows. In 2018, the last year for which data are available, the inflow dropped even further while the outflow remained at a similar level as in 2017, making the balance even more negative for the UK (Figure 1). Thus, it seems that the vision of Brexit did indeed deter some migrants from coming and encourage others to leave the UK.

Figure 1. Estimated number of Polish citizens (in thousands) coming to live in (inflows) and leaving the United Kingdom (outflows), 2005–2018

Source: ONS, International Passenger Survey (4.07 IPS Sex by Age by Citizenship).

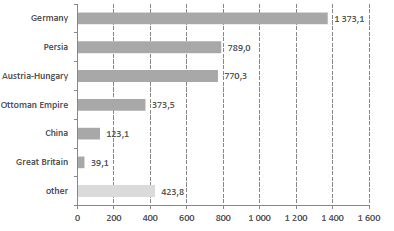

Data on citizenship granted to Poles illustrate a somewhat opposite reaction to Brexit, with the number of citizenships spiking after the referendum (Home Office 2020). To be granted citizenship, one needs to have lived in the UK for five years and then to have obtained an indefinite leave to remain, permanent residence or settled status; after 12 months, one can then apply for British citizenship. The whole process takes over six years and demands a significant investment of money and time, since applicants have to pass a ‘Life in the UK’ test and pay a fee of over £1 300 for applying. Holding dual Polish and British citizenship is allowed. Figure 2 shows that, in 2005–2009 the number of British citizenships granted to Polish citizens was small – below 1 000 a year. In 2008, during the GFC, the number fell. Then it gradually grew, with the first spike in 2013, probably due to an increased number of Poles having fulfilled the eligibility criteria after several years of residence. The second spike came after the Brexit referendum, which suggests a sudden increase in interest among those already eligible.

The above suggests that Brexit had a polarising effect: while the number of permanent residence and citizenship applications grew, so did the number of those who were leaving. The analysis presented in this article aims to identify the factors contributing to these seemingly contradictory reactions and migration intentions in response to Brexit among those Polish migrants who were still present in the UK two years after the referendum.

Figure 2. UK citizenships granted to Poles (total = 51 729), 2005–2019

Note: Includes registration and naturalisation.

Source: Home Office 2020, Citizenship grants by previous nationality (Cit_D01).

Situating migrants’ reactions to the Brexit referendum in the conceptual framework on post EU-enlargement mobility

Our interpretation of the post-EU-enlargement migrants’ diverse perceptions of the UK’s decision to leave the EU is grounded in the preceding scholarly narratives regarding this type of migration. The early interpretative frames concentrated on the flexibility and initial open-endedness of many migrants’ plans, using such concepts as ‘intentional unpredictability’ (Eade, Drinkwater and Garapich 2007), ‘deliberate indeterminacy’ (Moriarty, Wickham, Salamońska, Krings and Bobek 2010) and liquidity (Glorius, Grabowska-Lusińska and Kuvik 2013). This indeterminacy or liquidity, characteristic of the mobility of young new European citizens, as pointed out by Lulle et al. (2018), mostly means being flexible and open to opportunities but does not exclude enjoying security or stability. Instead, the flexibility has been based on the privileged status of EU citizens securing the freedom to move, stay and work in a (gradually enlarging) number of countries. This privileged status enabled some migrants to already be able to live not in one but in two or more countries, providing them with geographically dispersed networks and a knowledge of several locations (Ciobanu 2015; Salamońska 2017). Since the privileged status works for Europeans within the EU, some migrants obtain a new passport (such as a British one) to enable them to migrate further following a period of settlement in one country (Szewczyk 2016).

The new statistical trend of increasing outflow and decreasing inflow of Central and Eastern Europeans to the UK in the aftermath of the referendum could be interpreted as a display of the intentional unpredictability (Eade et al. 2007) or liquidity (Engbersen, Snel and de Boom 2010; Glorius et al. 2013) of migrant plans. According to these perspectives, a lack of long-term plans and reacting to the conditions and opportunities of the moment were particular features of post-accession migration, long underlined in regard to young migrants from Poland and other countries of Central and Eastern Europe. However, perceiving migrants as liquid raises an expectation of a massive movement when the circumstances worsen – a movement that has not materialised as the number of migrants leaving the UK is still modest.

Many migrants have remained in the UK despite Brexit. This is often explained using stability- or settlement-oriented perspectives (Grzymała-Kazłowska 2018; Ryan 2018), which claim that after ten or more years migrants may have reached a different stage in their life course and are not as liquid in their plans as they were previously, due to various ties or anchors to the spatial and socio-relational contexts of the country of residence. The factors which contributed to prolonging migrants’ stay and shifting to long-term orientations include, for example, family reunification and securing a home in the new location (White 2010), social relationships (Ryan 2018), a sense of dignity and ‘normality’ based on the affordability of everyday life (McGhee, Heath and Trevena 2012) and investing in children’s education (Rodriguez 2010) or their own career (Trevena 2013). Grzymała-Kazłowska (2018) introduced the term ‘anchoring’, referring to the process of developing such subjectively important ties and contributing to the migrant’s sense of stability and belonging. Proposing the term ‘differentiated embedding’, Ryan (2018) emphasised that the attachments, which resulted in the prolonging of the initially temporary stays of post-EU-accession migrants, develop in a non-linear dynamic process of negotiating social relations in multiple sites, structured by the spatial and temporal context. Again, it has to be remembered that these are not unidirectional processes as, along the evolving structural context and migrant’s life course, various ties in the country of origin and stay may change their relative importance. According to Kay and Trevena (2018), declared settlement can be an open-ended project depending on changing relations, resources, family needs or life course phase. As observed by Ryan, post-2004 accession migrants extending the initially temporary stay are comparable to the earlier waves of Irish migrants settling in the UK ‘who also enjoyed mobility rights and thus had opportunities to come and go, stay or return’ (2018: 234). From this perspective, prolonged indeterminacy and non-permanent settlement are not new features of post-accession migration but are, rather, features resulting from the legal privilege of citizenship of the freedom of movement area.

In the periods of the pre-Brexit referendum campaign, the shock from its results and the political disturbance regarding the timing and form of Brexit, the status of EU migrants has been an often discussed issue. This discourse undermined the migrants’ achieved stability and security, decreasing their quality of life and causing anxiety. Experiencing being unwelcome was perceived as painful, especially for the thus-far more privileged old member-state citizens (Brahic and Lallement 2020; Lulle et al. 2018). Although anti-immigrant and racist attitudes had been reported at least since the economic crisis of 2008 (Rzepnikowska 2019), and the government had already been creating a ‘hostile environment’ around migrants for some years (as described in detail by, for example, Burrell and Schweyher 2019), the referendum made it very clear to some EU citizens that, in spite of their privileged legal position, they also belonged in the category of migrants. From the liquidity perspective, the atmosphere during the Brexit negotiations could be interpreted as one discouraging migrants from staying in the UK, regardless of the legal changes to be introduced. Hence, a change of intentions to remain in reaction to Brexit could be expected. Yet, during the pre-referendum campaign, only a small proportion of Polish immigrants declared their intention to leave the UK if Brexit happened (McGhee et al. 2017). The relatively low popularity of this reaction was confirmed by the lack of any dramatic ‘Brexodus’ in the ONS migration statistics published since 2016.

Why is the reaction of post-EU accession migrants to the possible leaving of the EU by the UK so limited? Why was there no Brexodus? The answer can be partly found in the analysis of migrants’ reactions to the previous shock of the Global Financial Crisis when, contrary to the expectations of migrants’ rapid reactions to the economic downturn, many Polish migrants stayed abroad (Janicka and Kaczmarczyk 2016). Since the GFC, repeated questionnaire surveys of Polish migrants have shown a decrease in short-term mobility and a prevalence of more long-term migrants among Poles in the main EU destination countries (Janicka and Kaczmarczyk 2016). Furthermore, Jancewicz and Markowski (2019) have shown that length of stay, higher earnings and owning real estate are all associated with the settlement intentions of Poles remaining abroad. This confirms that those migrants who have developed attachments and long-term plans related to the country of immigration are less prone to react to external shocks by emigrating. Post-accession migrants have already invested greatly in their ties to the British labour market and society, so emigration from the UK (be it to return to Poland or for further migration) could incur a considerable loss of UK-specific capital, especially that related to professional qualifications and networks (Erel and Ryan 2019). That is why, in the context of uncertainty around Brexit, we expect that migrants who invested in their UK-specific skills and achieved job stability will not take the decision to leave lightly as it may be more profitable to postpone the move (cf. Burda 1995), stay in the UK and continue earning there for as long as possible.

Economists point to (lifetime) earnings as a primary factor in migration decision-making, often disregarding other aspects related to moving to a new place (e.g. Borjas 2014). However, even when using such a financially oriented framework, we find that the cultural, institutional and social aspects of the host country do matter as they indirectly influence economic possibilities, decisions and outcomes. Similarly, we see that the Brexit referendum results, which initially concerned the rules of stay, also deeply touched the emotions of migrants and their feelings of being at home. Later, it translated into uncertainty in both the legal and the economic realms, as the Brexit process influences not only employers’ attitudes toward migrants but the condition of the whole economy of Britain (Portes and Forte 2017). According to Lulle, King, Dvorakova and Szkudlarek (2019), the way in which the Brexit referendum changed the institutional landscape for new EU state citizens in the UK introduced into their lives a new layer of uncertainty. At the time when our survey was conducted (June–September 2018), the future legal status of Poles in the UK was unclear. No withdrawal agreement had yet been negotiated between the EU and the UK. As Gawlewicz and Sotkasiira (2020) notice in their study of Poles in Scotland, this was long enough after the referendum for people to get over the initial shock of the result and adopt a calmer, more rational attitude. Nevertheless, apart from economic precarity, migrants had to face the fact that comparing their possible future in the UK with a possible future in another country became even more difficult – they had to introduce more unknowns into the equation. Thus, we expected that the number of those who just did not know what their plans were might have increased due to the possibility of Brexit.

The perspective of the UK’s leaving the EU brought to the fore the thus far largely ignored sphere of the legal integration of intra-EU migrants. The change in the legal rules of stay concerning EU citizens who have migrated to the UK and also their family members such as aging relatives (see Radziwinowiczówna, Kloc-Nowak and Rosińska 2020) and partners of various nationalities (including non-EU) means that keeping one’s options open, leading a translocal life and maintaining ties in both countries may no longer be possible. Securing the right to live a normal life in the UK (including work and welfare rights) requires obtaining confirmation of one’s settled status. Even those who have so far displayed their preference for transnational living and who have not intended to settle in the UK permanently may have incentives to prolong their stay and invest their time in obtaining tangible proof of their ties to the UK – a permanent residence certificate or citizenship (McGhee et al. 2017). This complicates the interpretation of migrants’ intentions regarding their length of stay in the UK, as the declaration of prolonging the stay may display a wish to secure legal status and not necessarily to settle permanently.

Incorporating Brexit into the push–pull framework

In line with Lee’s (1966) push–pull framework, later used and modified by many scholars (for example, Bodvarsson and van den Berg 2009; de Jong and Fawcett 1981; Fihel 2018), the factors influencing migrants’ decisions can be divided into: factors associated with the area of origin and/or with the destination; intervening obstacles (such as distance, costs of transportation and physical or political barriers, such as access to legal residence and work); and personal factors (such as age, level of education or the stage of the life cycle) which frequently moderate the influence of the first three factors. On both the origin and destination sides, ‘plus’ and ‘minus’ factors operate (termed by scholars variously as ‘pull’, ‘retain’, ‘stick’, ‘stay’ or ‘push’, ‘repel’ factors – Carling and Bivand Erdal 2014; Chebel d’Appollonia and Reich 2010). Migrants respond to their own perceptions of these factors, as nobody holds full information about the conditions at origin and, especially, at destination.

Before Brexit became an issue, a large body of literature explored the factors which influenced the decisions of Polish migrants to the UK. Economic factors, especially unemployment, low wages and, somewhat later, precarious work conditions – such as contracts without health and old-age insurance – seem to have been the dominant push factors making migrants leave Poland (Jończy 2010; Okólski and Salt 2014). On the pull side, the list of factors seemed somewhat more diverse. Economic factors, such as the availability of employment and high wages, were key (Jończy 2010; Milewski and Ruszczak-Żbikowska 2008; Okólski and Salt 2014). However, many studies demonstrated that, especially for the young and well-educated, cultural factors such as wanting to learn English, live in a global metropolis or experience multiculturalism were also important (Isański, Mleczko and Seredyńska-Abu Eid 2014; Luthra, Platt and Salamońska 2018; Salamońska 2012). These factors, as well as social factors such as the presence of family and friends in both the origin and the destination countries, were important at the moment of the initial decision, as well as on every following day, when the migrants again chose to either remain where they were or to depart. Some scholars have also pointed out that life stage is important in the migrants’ decisions, especially since many have gone from being twenty-something and single to having families and children, which proves to be a strong factor keeping migrants in place (Ryan 2015; Ryan and Sales 2013; Trevena 2013, 2014; White 2010). Overall, there are many factors proven to impact on migrants’ perceptions of life in the UK, of which Brexit should be considered as another, albeit new, influence.

We therefore construct our hypotheses regarding Brexit’s impact on respondents’ perceptions by relying on previous findings about the factors that push and pull migrants towards and out of the UK. We expect that, while push and pull factors at origin and at destination still operate, Brexit and the resulting legal changes will have an uneven influence on the various groups of migrants and, thus, should lead to different perceptions. Nevertheless, since the opening of the labour market post-EU accession (and all the related rights) was the impulse for the massive inflow of Poles to the UK, we do expect that most migrants will perceive Brexit as a significant change for the worse. Hence we hypothesise that:

(H1) Brexit is an important factor discouraging a large share of Polish migrants from staying in the UK.

We assume that the varying impacts of Brexit on migrants depending on their characteristics will translate into different propensities for those migrants to consider Brexit as a factor discouraging them from staying. We devoted particular attention to the individual characteristics which we believed to be the strongest shields against the negative impact of Brexit: legal status and the acquisition of locally recognised qualifications or education.

(H2) For those for whom the legal situation would not change – for example, because they already had British citizenship or another status allowing them to remain indefinitely – Brexit would not be a factor discouraging them from remaining in the UK.

(H3) For people who had invested into their human capital in the UK, by finishing secondary or post-secondary education, studying for a degree or taking part in long professional courses Brexit would be unlikely to discourage them from remaining in the UK, as their increased human capital investment anchors them to the specific British labour market and protects them from changes in British immigration regulations.

We also consider that strong anchors and ties to the UK would give migrants both the motivation and means to guard against the negative impact of Brexit, making them less likely to perceive Brexit as a discouraging factor. We addressed such potential anchors through indicators related to the various dimensions of integration for the following hypotheses:

(H4) Those who had attachments in the UK – such as living with a spouse or partner who has British citizenship, owning real estate in the UK or belonging to an organisation or club – would be less likely to point to Brexit, or other factors, as discouraging.

(H5) On the contrary, those who did not have such attachments (evident in their failure to learn English very well) or who still had attachments in Poland (evident in remittances), would be more likely to point to factors, especially Brexit, discouraging them from staying.

Last but not least, we expected that people’s economic situation in the UK may affect the impact that Brexit might have on them and thus their perception of Brexit. Given that most of the initial economic pull factors, as described in the literature, remain in force, we hypothesised that:

(H6) Those who were in a poor or unstable economic situation in the UK, for example people without permanent contracts, those performing low-skilled jobs or those who were welfare recipients, would be more likely to perceive Brexit as a factor discouraging them from staying in the UK, as it could negatively affect their situation more than that of other groups.

Methods

Data and survey structure

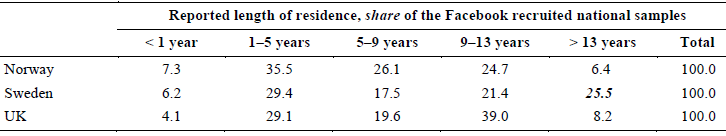

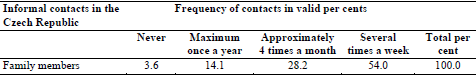

This paper presents the results from a survey of long-term Polish migrants in the UK conducted between June and September 2018 by the Centre of Migration Research (CMR), University of Warsaw. All the respondents had to be Polish citizens and long-term migrants, meaning that they arrived in the UK as adults between 1 January 2000 and 1 January 2014 and had been living in the UK at least for 4.5 years before the date of the survey. This means that the youngest respondent could be 22 years old as the study was conducted in mid-2018, and the oldest respondent 44 years old (migrants in this age bracket are the majority of the Polish-born population of the UK – ONS 2018).

To obtain as representative a sample as possible, the CMR survey used geographically and age-stratified quota sampling, analogous to that devised by the National Bank of Poland (NBP) for its biannual survey of Polish migrants (for details see Chmielewska, Dobroczek and Strzelecki 2018). The quotas were calculated based on the migrant population structure derived from the 2011 UK census. The UK was divided into eight geographical regions within each of which the quotas reflected the age structure of the study population in that region. Additionally, overall sample quotas were imposed to ensure the gender balance (the percentage of women had to be between 40 and 60 per cent), the focus on working migrants (at least 75 per cent of the sample had to be working, even if only for a few hours a week) and the professional group diversity (each of the four professional groups1 constituted at least 10 per cent of the sample). In sum, the sample design guaranteed that respondents’ profiles were diverse. Overall, the CMR survey included 472 respondents.

The interviews were conducted face-to-face using CAPI (Computer Assisted Personal Interviews). To ensure diversity and guard against interviewer-induced bias, recruitment through snowballing was prohibited and the number of interviews per interviewer and per location was capped. Using CAPI enabled confirmation of the geographical location of the interview and selective telephone post-verification (and in a few cases clarification) of the responses. Control over the fieldwork is a strength of this survey, compared to recent quantitative studies of Polish migrants in the UK which were self-administered online on a population targeted via Polish diasporic media (cf. Łużniak-Piecha, Golińska, Czubińska and Kulczyk 2018; McGhee et al. 2017). Another strength is that the interviewers spoke Polish fluently and the whole questionnaire was in Polish, which enabled all Polish migrants to participate. The survey did not raise significant ethical concerns, because it was anonymous, only adults could participate, and only after expressing their informed consent to the interviewers. The most sensitive areas, such as their economic situation allowed the respondents to refuse an answer. The dataset we received for analysis was anonymised. Based on the sampling and fieldwork approach, we believe that our survey offers a quite reliable cross-section of the Polish economically active long-term immigrant population in the UK of reproductive age.

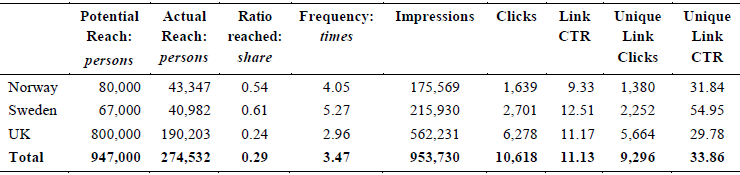

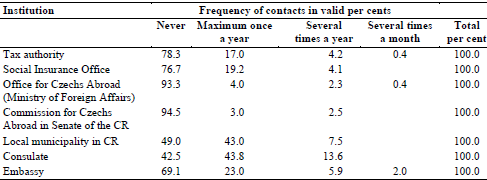

The survey data in comparison

Following McGhee et al. (2017) we evaluate the representativeness of our sample by comparing its descriptive statistics with those from the Annual Population Survey (APS, data from January to December 2018). The APS combines data from the UK’s Labour Force Survey to provide estimates of crucial variables in between the censuses. While the APS has its limitations, it is currently the best source of data for comparison. In the 2018 APS data, 1 410 respondents match the scope of our survey (i.e. they have a Polish passport, are aged 22–44, came to the UK for their current stay between 2000 and 2013 and were already 18 years old when they arrived). Table 1 compares the characteristics of the two samples while Figure 3 focuses on the year of arrival in both studies. The general trend in Figure 3 is similar for both studies, with a large number of respondents who arrived shortly after 2004, followed by a dip, and then a gradual increase due to those who came more recently. However, the first rise is more pronounced in the APS sample so, similarly to McGhee et al. (2017), Poles included in it arrived in the UK on average earlier than those in the CMR study. These latter participants were on average two years younger, less likely to be married and more likely to have a post-secondary education than those in the APS sample.

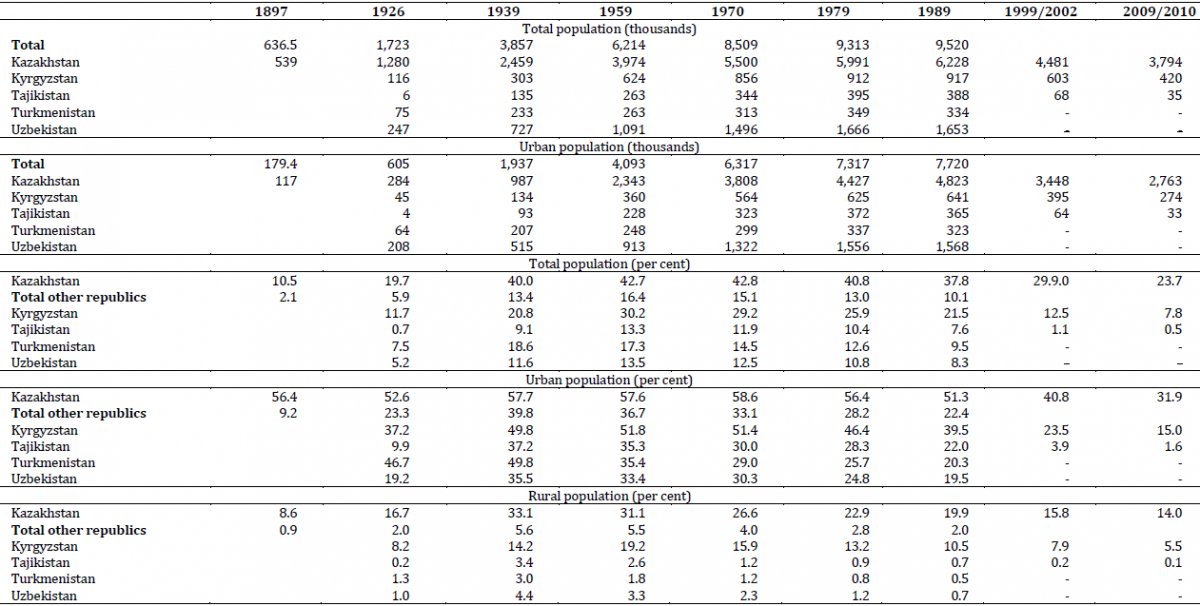

Table 1. Comparison of sample characteristics of the CMR survey with the APS 2018 data

Notes: * Only APS respondents who would qualify for the CMR survey are included in the comparative sample; ** For APS these were respondents with qualifications [HIQUL15D] categorised as ‘Degree or equivalent’ or ‘Higher education’.

Figure 3. Year of arrival of APS and CMR survey participants

Source: APS (2018); N = 1 410; CMR (2018) survey; N = 472.

Analysis

We focus on the CMR survey question ‘What, if anything, discourages you from staying in the UK?’, asked immediately after an almost identical one about what encourages them to stay. Each participant could choose 2 out of 13 encouraging factors, while, in the second question they could chose 2 out of 11 discouraging ones, as presented in Figure 4. Brexit was one possible answer but there were a number of others related to the economic situation, cultural preferences and social situation of migrants. We interpret our respondents’ declarations not as reasons for actual moves but, rather, as indicators of how migrants evaluate each location and explanation for their declared migration or settlement intentions. Choosing Brexit or any other discouraging factor from the list did not mean that the respondent planned to leave the UK but indicated a potential push factor which was taken into consideration in decisions on whether or not to move.

In this article, we conduct both a univariate and a multivariate analysis of the CMR survey data. First, we examine respondents’ Brexit-related answers to verify H1 and to provide a background for further analysis. Second, to verify Hypotheses 2–6, we perform a multinomial logistic regression with grouped answers to ‘What, if anything, discourages you from staying in the UK?’ as the dependent variable. Respondents who answered ‘Nothing discourages me’ serve as the reference category. In this context, we distinguish two groups of respondents: those who chose some discouraging factors (related to economic, cultural, familial issues etc.) but not Brexit, and those who chose ‘Changes brought by Brexit’ (possibly together with one other factor). The latter are the focus of our analysis. We distinguished them from the respondents who considered that nothing discouraged them and those who chose some discouraging factors, because we believe that they constitute contrasting groups in their reaction to Brexit and possibly to other future changes and we wanted to compare their characteristics. We calculated three multinomial regression models: the first includes only respondents’ demographics, the second includes demographics and non-economic integration-related variables, while the third model includes demographics and economic-integration variables. The choice of independent variables stemmed from our literature review and hypotheses. We recoded and/or regrouped independent variables to ensure that each category was large enough to provide a statistically sound model. We performed the multivariate analysis using the ‘nnet’ package in the R software.

Results: what our survey data show

The focus of this article follows the logic of the push–pull framework (Lee 1966) in which we asked respondents what encouraged/discouraged them from staying in the UK. Figure 4 shows that the most common encouraging factor was the level of earnings and the second was the job situation, followed by lifestyle/culture at work. The most common answer to the question about discouraging factors was ‘nothing’, chosen by over half of the respondents. Only 15 per cent (71 respondents) indicated changes brought on by the Brexit referendum, closely followed by respondents who were discouraged by the UK’s cultural diversity. Overall, 30.5 per cent of respondents (144 respondents) pointed to some factor(s) discouraging them from staying in the UK but did not point to Brexit. In a similar question about what encourages respondents to return to Poland and what discourages them from returning home, over half chose insufficient earnings, followed by the high cost of living and the difficulties in finding a job. We can therefore see that, while Brexit may have caused very emotional reactions, it is still one among many factors and it is the economic reasons which influence many migrants’ perceptions the most. On that front, the UK is still the right place to be for many migrants. Therefore, we find the first hypothesis (H1) not confirmed because, while changes brought by Brexit were the most common discouraging factor, only one in seven respondents indicated that it actually discouraged them, while those whom nothing discouraged constituted a majority.

The fact that most respondents said that nothing discouraged them from staying in the UK is surprising, as their legal status could change because of Brexit. However, Figure 5 shows that roughly one in three respondents agreed or strongly agreed with ‘I have concerns about my legal status allowing me to stay and work in the UK’, around one in five expressed ambivalence, while almost one in two disagreed. Overall, the survey participants seemed to worry little about their rights in the UK. We suspect that this lack of concern can stem from their being confident that they can ensure their right to stay (e.g. by applying for citizenship or a residence status certificate) or from planning to leave soon anyway.

Figure 4. Factors chosen by respondents as encouraging or discouraging them from staying in the UK (%)

Source: CMR (2018) study; N = 472.

In order to verify this, Figure 6 shows how long the survey participants planned to stay in the UK. In line with the intentional unpredictability suggested by Eade et al. (2007), over half of the sample indicated that they did not yet know. The results of other surveys of Polish migrants in the UK (e.g. Chmielewska et al. 2018), leads us to suspect that, when the option ‘I don't know’ is hidden, many respondents merely estimate the length of any further stay, although other studies also show a high level of uncertainty about the remaining or leaving plans of migrants (Drinkwater and Garapich 2015). Aside from those respondents who reported no concrete plans, one in four indicated that they planned to stay forever, and only one in seven had a definitely planned date of return (or further migration). Overall, a lack of concrete plans to remain prevailed in our sample.

Figure 5. Respondents’ reactions to ‘I have concerns about my legal status allowing me to stay and work in the UK’ (%)

Source: CMR (2018) study; N = 472.

Figure 6. Migration plans of surveyed respondents (%)

Note: The middle three answers (I plan to stay: longer than 5 years, 2–5 years, 0–2 years) are grouped categories from a precise answer on respondents’ planned length of stay.

Source: CMR (2018) survey study, N = 472.

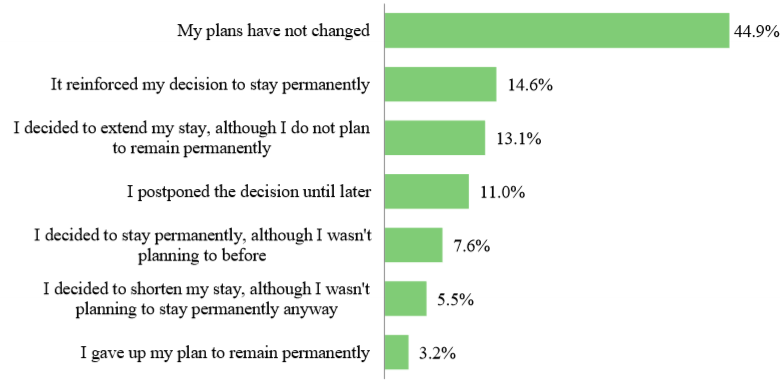

We now turn to gauging how Brexit influenced respondents’ plans. Figure 7 shows that almost half of our respondents said that the Brexit referendum did not influence their plans while, for around one in ten, it made them postpone the decision over whether or not to remain in the UK. Surprisingly, more than one in three respondents indicated that Brexit’s impact on their length of stay was positive. This group declared that the referendum reinforced their decision to settle (14.6 per cent) and prompted them to stay longer (13.1 per cent) or permanently (7.6 per cent). In contrast, only 8.7 per cent of the sample shortened their planned stay or decided not to stay permanently due to the referendum. This confirms the refutation of our first hypothesis. Respondents’ declarations, together with citizenship and inflow/outflow data suggest that the referendum, if anything, prompted people to rethink their options. Some decided to shorten their stay (among whom a number had already left) but a significant number chose to remain longer, sometimes even forever, or at least long enough to ensure their right to do so.

Which migrants are discouraged by Brexit?

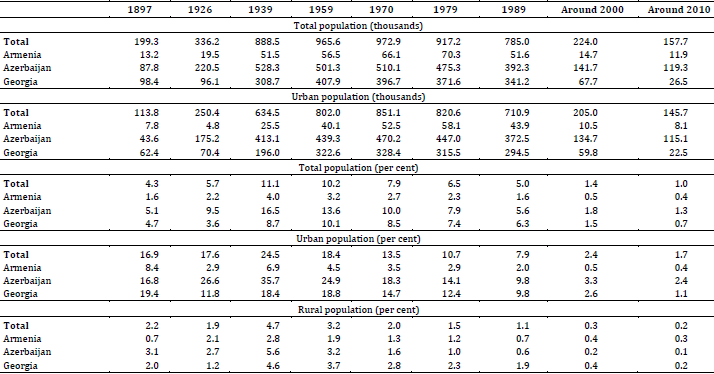

The Brexit referendum induced different reactions and, as we hypothesised, had an uneven influence on migrants’ perceptions, which were associated with their individual situations and characteristics. Therefore, we deepen our analysis in order to verify our expectations. Tables 2, 3 and 4 show the results of three multinomial regression models, the first of which (Table 2) includes only basic demographic variables, the second (Table 3) adds non-economic integration indicators and the third (Table 4) contains demographic variables and economic-integration indicators. All the models try to distinguish between respondents who pointed to Brexit as a discouraging factor (15 per cent of the sample), those who indicated that they find some factors – but not Brexit – discouraging (30.5 per cent of the sample) and the 54.4 per cent who declared that they find nothing to discourage them from staying in the UK. The latter group acts as the reference category.

Figure 7. Respondents’ answers to ‘How did Brexit influence your plans?’ (%)

Source: CMR (2018) survey; N = 472.

The first model, shown in Table 2, suggests that traditional demographic variables such as gender, age, educational attainment or marital status cannot explain which respondents found Brexit discouraging. Even the length of stay in the UK, a variable typically crucial for all migration-related outcomes, has in this basic model a marginal and potentially random effect. Interestingly, another aspect of the respondents’ migration histories influenced the predicted odds. Those respondents with experience of migration to countries other than the UK were more likely to point to Brexit, but not necessarily to other factors, as discouraging. To be more precise, Model 1 estimates that those with experience of multiple migration (other things held constant) were 2.65 times more likely to choose Brexit as the discouraging factor than those who had migrated only to the UK. Possibly, respondents experienced in multiple relocations were able to compare their situation in the UK to that found in other countries and were more open to another relocation if the UK became comparatively less attractive.

Table 2. Coefficients of multinomial logistic regression

Notes: The dependent variable is based on answers to ‘What, if anything, discourages you from staying in the UK?’ The reference category for the dependent variable is ‘Nothing discourages me’.

The second model incorporates demographic controls and indicators related to non-economic integration. The coefficients shown in Table 3 confirm H2 – that those with a secure legal situation were less likely to answer that Brexit was a factor discouraging them from staying in the UK. However, we find H3 not confirmed – the variable reflecting whether someone completed a professional course lasting longer than 6 months or finished secondary/post-secondary education in the UK, had little influence on the predicted probabilities. Even when, in other models, we considered more narrowly only those who had studied in the UK, the impact was still negligible. It seems that investing in human capital in the UK only had a small influence on respondents’ perceptions of Brexit.

Attachments to the UK or integration into British society was an important hypothesis. H4 states that those who created attachments – or rather, those who seem to have done so, as we have only some indicators of these – would be less likely to consider Brexit a discouraging factor. The results – as shown in Table 3 – are mixed. In line with the hypothesis, respondents living with a partner or a spouse who had a British passport were more likely to find nothing discouraging them from staying in the UK. Nevertheless, this association was strong only when comparing those who chose ‘nothing’ with those who chose ‘something other than Brexit’ as discouraging. Having real estate in the UK seems to have no statistically significant impact, contrary to our predictions. Furthermore, while belonging to an organisation, association or club did influence predicted probabilities, this influence went in the opposite direction. When comparing those who chose ‘nothing’ with those who chose Brexit as a discouraging factor, belonging to an organisation, association or club more than doubled the odds of finding Brexit discouraging. Thus, we find H4 not confirmed.

Hypothesis 5 focused on indicators suggesting a difficulty in making attachments to the UK or keeping strong attachments to Poland; we expected these to increase the chances of finding something – and Brexit in particular – discouraging. We find H5 partially confirmed. Knowing English badly or not at all after a more than four-years stay in the UK, had a weak relationship to finding Brexit discouraging, but did correspond with a higher predicted probability of finding something (not Brexit) discouraging Poles from staying in the UK. Table 3 also confirmed that sending remittances to Poland strongly increased the odds of choosing both something and Brexit as discouraging.

Table 3. Coefficients of multinomial logistic regression

Notes: Respondents who chose ‘Nothing discourages me’ act as the reference group. The dependent variable is based on answers to ‘What, if anything, discourages you from staying in the UK?’. Model 2 incorporates demographics and non-economic integration indicators.

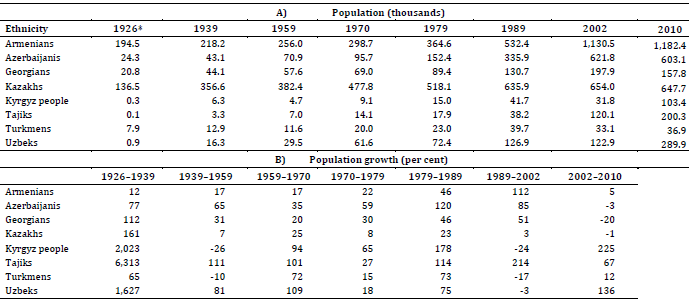

The third model, shown in Table 4, incorporates not only demographic variables but also indicators of economic integration. Hypothesis 6 stated that those in a poor or unstable economic situation in the UK would be more likely to perceive Brexit as discouraging. Here, again, the results are mixed. The predicted odds for those performing jobs that require high qualifications – e.g. specialists, doctors, engineers, technicians – differed only slightly from the odds for those who performed simple jobs. In contrast, those in median-level jobs, such as industrial workers, machinery and equipment operators or office and qualified service employees, were less likely to find Brexit discouraging. This was perhaps because those performing simple jobs, together with the elites, could transfer their skills elsewhere, while those performing median-level jobs had acquired qualifications recognised mainly in the UK, so for them leaving would be costly. Respondents working on permanent contracts were less likely to choose a factor (but not Brexit) as discouraging them from staying in the UK than those without permanent contracts. The relationship with choosing Brexit went in the same direction but was much weaker. Finally, the odds for receivers of welfare benefits to indicate Brexit as a discouraging factor were 2.18 times the odds of those not receiving benefits, in line with our hypothesis. Thus, the expected relationship was strongly visible only among those respondents who rely on state support, which might be limited by Brexit, directly impacting those migrants’ incomes. In general, out of the three models presented, this last one has the highest predictive power (with a modest Nagelkerke’s R2 of 0.237), implying that respondents’ economic situation plays a role in shaping their perceptions of Brexit.

Table 4. Coefficients of multinomial logistic regression

Notes: The reference category for the dependent variable is ‘Nothing discourages me’, while for the ‘Type of work’ variable the reference category is: ‘People doing simple jobs’. The dependent variable is based on answers to ‘What, if anything, discourages you from staying in the UK?’. Model 3 incorporates demographics and economic integration indicators.

Discussion and conclusions

Many researchers and political commentators expected that the uncertainty introduced by Brexit and the atmosphere of anxiety and hostility towards foreigners would have a significant influence on departures and departure plans. However, only one in seven long-term migrants questioned here stated that they consider Brexit a factor discouraging them from staying in the UK. In general, the survey results interpreted within a push–pull framework showed that economic factors such as earnings level, job situation and professional development, were more common in migrants’ answers than Brexit itself. One of the reasons why respondents did not consider Brexit particularly discouraging might be that they seem to worry little about their legal status, suggesting that long-term migrants in the UK believe that they have ways to ensure further stay and work rights. Therefore, it is no surprise that 45 per cent of respondents reported that Brexit had no impact on their plans and, in fact, many said it actually convinced them to stay longer. Despite expectations, it seems that, for some, Brexit turned out to be a ‘stick’ or ‘stay’ factor, as termed by Lee’s followers (Chebel d’Appollonia and Reich 2010; Herbst, Kaczmarczyk and Wόjcik 2017). In general, our results support Kilkey and Ryan’s (2020) conclusions that the referendum was an unsettling event. It was unsettling enough to prompt migrants to rethink their options and possibly secure their status but not necessarily to leave.

The official statistics support the interpretation that the Brexit referendum led both migrants and potential migrants to reconsider their plans. On the one hand, some migrants left and many others did not come, a reaction similar to the reaction to the Global Financial Crisis. On the other hand, unlike during the GFC, the number of Poles requesting and then being granted British citizenship spiked. Reconsidering one’s options, however, does not necessarily mean making definite plans, as our survey results suggest that many long-term migrants still remain uncertain about how long they will stay. We do not know whether – in line with Eade et al.’s original conceptualisation (2007) – their unpredictability is still intentional or whether it has become somewhat unintentional and forced upon them by changing British regulations; nevertheless, as seen in many previous studies (Eade et al. 2007; Glorius et al. 2013; Moriarty et al. 2010), the lack of concrete plans to migrate or to remain was prevalent among our respondents.

Our results confirm that holders of British citizenship or permanent residence documents were less likely to perceive Brexit as a factor discouraging them from staying in the UK. However, this relationship might stem from two sources. First, those who already have ensured their right to legally remain feel (partially) immune to Brexit’s negative consequences for immigrants. Second, those previously concerned about Brexit had been more likely to apply for both citizenship and other statuses which would ensure their right to stay and ease their concerns. Nevertheless, respondents’ legal integration went hand-in-hand with their being less likely to perceive Brexit as discouraging.

Belonging-oriented perspectives (Grzymala-Kazlowska 2018; Ryan 2018), as well as integration and transnationalism theories (e.g. Carling and Pettersen 2014) suggest that migrants who created multiple attachments that keep them rooted in the UK would not get easily discouraged from remaining there. However, our results indicate that only some such attachments lead to lower odds of perceiving Brexit, or another factor, as a discouragement to staying in the UK. Investing in education or having real estate in the UK had a negligible impact on the respondents’ perceptions of Brexit as discouraging. Respondents working on permanent contracts and those living with a partner/spouse with a British passport were less likely to point to a factor discouraging them from staying; those who still knew English badly or not at all, and those who remitted to Poland were, on the contrary, more likely to find something discouraging. Thus, we can see that, among many personal characteristics, only some mattered. The odds of choosing Brexit (in comparison to choosing nothing) as discouraging Poles from staying in the UK were lower for those working in median-level jobs (industrial workers, machinery and equipment operators, or office and qualified service employees) and higher for those who had previously migrated to other countries too, those who belonged to an organisation, association or club, those who remitted to Poland, as well as those who received welfare benefits. Overall, there are some simple patterns – e.g. those economically dependent on British welfare benefits were more prone to feel discouraged, perhaps because they were worried about losing their financial security. Other patterns were mixed or nuanced, suggesting the need for further research into what influences migrants’ perceptions.

In general, economic indicators gave us the best predictions of who would be discouraged by Brexit (the regression model incorporating economic variables had the highest predictive power, albeit still a modest one). Furthermore, interviewees the most often pointed to high earnings, a good job situation, the work culture and the potential for career development as factors that encouraged them to stay in the UK. This suggests that, while Brexit elicited a very emotional reaction from migrants, it did not (yet) overshadow the pull factors the most important to them, which seem to be economic in nature. Therefore, we suspect that, as long as the UK offers Polish migrants satisfying economic opportunities, many will decide to stay, despite the negative emotions and atmosphere following the Brexit referendum and its impact on migrants’ quality of life. However, if Brexit or another factor affects the economy, if earnings fall, job options become limited and the potential for development decreases, we can expect these changes to push migrants to search for better opportunities elsewhere.

Nevertheless, our study has its limitations. It is important to stress that the sample consisted of migrants who were still living in the UK two years after the Brexit referendum. Thus, in interpreting the results we have to bear in mind the statistics presented in the section on inflows and outflows of Polish citizens to and from the UK before our study took place. It is possible that those migrants who were the most afraid of Brexit reacted very swiftly and left before our survey. Qualitative research could complement our study and reveal the more complex processes influencing migrants’ perceptions and decisions – for example, the extent to which they evaluate Brexit’s consequences for them as immigrants or as British residents, entrepreneurs or taxpayers. The region of residence, sector of employment, political views or even psychological characteristics in reaction to uncertainty could differentiate migrants’ responses to this political challenge. Longitudinal surveys, random sampling and larger samples would allow for the verification and a better understanding of the patterns found here and the way in which they may unfold over time, as the changes caused by Brexit materialise in the UK.

Notes

1 A division into four work type / professional groups was used: (1) people doing simple jobs; (2) industrial workers, machinery operators; (3) office and qualified service employees; and (4) highly qualified specialists, managers, technicians (e.g. doctors, engineers). Those without work were categorised into a fifth group, who could potentially constitute up to 25 per cent of the sample: ‘I currently do not work in the UK’.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Polish Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy for letting them use the data from the CMR survey they co-financed to study the Readiness of Polish Post-Accession Migrants to Return to Poland – Analysis in the Context of Fertility and Family Policy in Poland [Badanie dotyczące gotowości polskich migrantów poakcesyjnych do powrotu do kraju w kontekście dzietności i polityki prorodzinnej w Polsce]. We are also grateful to the referees, the journal and the special issue editors for helpful comments and suggestions. All errors and omissions are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Polish National Research Foundation (NCN) under Grant OPUS 10 [2015/19/B/HS4/00364 The Impact of Wealth Formation by Economic Migrants on their Mobility and Integration: Polish Migrants in Countries of the European Community and Australia].

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID IDs

Barbara Jancewicz  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2636-872X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2636-872X

Weronika Kloc-Nowak  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9213-4134

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9213-4134

Dominika Pszczółkowska  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7812-1548

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7812-1548

References

Bodvarsson O., van den Berg H. (2009). The Economics of Immigration. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Borjas G. J. (2014). Immigration Economics. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press.

Brahic B., Lallement M. (2020). From ‘Expats’ to ‘Migrants’: Strategies of Resilience among French Movers in Post-Brexit Manchester. Migration and Development 9(1): 8–24.

Burda M. C. (1995). Migration and the Option Value of Waiting. Economic and Social Review 27(1): 1–19.

Burrell K., Schweyher M. (2019). Conditional Citizens and Hostile Environments: Polish Migrants in Pre-Brexit Britain. Geoforum 106: 193–201.

Carling J., Bivand Erdal M. (2014). Return Migration and Transnationalism: How Are the Two Connected? International Migration 52(6): 2–12.

Carling J., Pettersen S. V. (2014). Return Migration Intentions in the Integration-Transnationalism Matrix. International Migration 52(6): 13–30.

Chebel d’Appollonia A., Reich S. (2010). Managing Ethnic Diversity after 9/11: Integration, Security, and Civil Liberties in Transatlantic Perspective. New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Chmielewska I., Dobroczek G., Strzelecki P. (2018). Polish Citizens Working Abroad in 2016: Report of the Survey for the National Bank of Poland. Warsaw: University of Warsaw.

Ciobanu R. O. (2015). Multiple Migration Flows of Romanians. Mobilities 10(3): 466–485.

de Jong G. F., Fawcett J. T. (1981). Motivations for Migration: An Assessment and a Value-Expectancy Research Model, in: G. F. de Jong, J. T. Fawcett (eds), Migration Decision-Making: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Microlevel Studies in Developed and Developing Countries, pp. 13–58. New York: Pergamon.

Drinkwater S., Garapich M. P. (2015). Migration Strategies of Polish Migrants: Do They Have Any at All? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41(12): 1909–1931.

Eade J., Drinkwater S., Garapich M. P. (2007). Class and Ethnicity: Polish Migrant Workers in London. CRONEM Research Report. Guildford: University of Surrey.

Engbersen G., Snel E., de Boom J. (2010). A Van Full of Poles’: Liquid Migration from Central and Eastern Europe, in: R. Black, G. Engbersen, M. Okólski, C. Pantiru (eds), A Continent Moving West? EU Enlargement and Labour Migration from Central and Eastern Europe, pp. 115–140. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Entzinger H., Biezeveld R. (2003). Benchmarking in Immigrant Integration. ERCOMER Research Report. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Erel U., Ryan L. (2019). Migrant Capitals: Proposing a Multi-Level Spatio-Temporal Analytical Framework. Sociology 53(2): 246–263.

Fihel A. (2018). Przyczyny migracji, in: M. Lesińska, M. Okólski (eds), 25 wykładów o migracjach, pp. 68–80. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Gawlewicz A., Sotkasiira T. (2020). Revisiting Geographies of Temporalities: The Significance of Time in Migrant Responses to Brexit. Population, Space and Place 26(1): e2275.

Glorius B., Grabowska-Lusińska I., Kuvik A. (eds) (2013). Mobility in Transition: Migration Patterns after EU Enlargement. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Grzymala-Kazlowska A. (2018). From Connecting to Social Anchoring: Adaptation and ‘Settlement’ of Polish Migrants in the UK. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44(2): 252–269.

Guma T., Dafydd Jones R. (2019). ‘Where Are We Going To Go Now?’ European Union Migrants’ Experiences of Hostility, Anxiety, and (Non-)Belonging during Brexit: EU Migration, Belonging and Brexit. Population, Space and Place 25(1): e2198.

Herbst M., Kaczmarczyk P., Wójcik P. (2017). Migration of Graduates within a Sequential Decision Framework: Evidence from Poland. Central European Economic Journal 1(48): 1–18.

Home Office (2020). Immigration Statistics: Citizenship. London: Home Office. Online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/managed-migration-da... (accessed: 30 June 2020).

Isański J., Mleczko A., Seredyńska-Abu Eid R. (2014). Polish Contemporary Migration: From Co-Migrants to Project ME. International Migration 52(1): 4–21.

Jancewicz B., Markowski S. (2019). Economic Turbulence and Labour Migrants’ Mobility Intentions: Polish Migrants in the United Kingdom, Ireland, the Netherlands and Germany 2009–2016. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27 August, doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1656059.

Janicka A., Kaczmarczyk P. (2016). Mobilities in the Crisis and Post-Crisis Times: Migration Strategies of Poles on the EU Labour Market. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42(10): 1693–1710.

Jończy R. (2010). Migracje zagraniczne z obszarów wiejskich województwa opolskiego po akcesji Polski do Unii Europejskiej. Wybrane aspekty ekonomiczne i demograficzne. Opole, Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Instytut Śląski.

Kay R., Trevena P. (2018). (In)Security, Family and Settlement: Migration Decisions amongst Central and East European Families in Scotland. Central and Eastern European Migration Review 7(1): 17–33.

Kilkey M., Ryan L. (2020). Unsettling Events: Understanding Migrants’ Responses to Geopolitical Transformative Episodes through a Life Course Lens. Transforming Mobility and Immobility: Brexit and Beyond. International Migration Review, 3 March, doi: 10.1177/0197918320905507.

Lee E. S. (1966). A Theory of Migration. Demography 3(1): 47–57.

Lulle A., King R., Dvorakova V., Szkudlarek A. (2019). Between Disruptions and Connections: ‘New’ European Union Migrants in the United Kingdom Before and After the Brexit. Population, Space and Place 25(1): e2200.

Lulle A., Moroşanu L., King R. (2018). And Then Came Brexit: Experiences and Future Plans of Young EU Migrants in the London Region. Population, Space and Place 24(1): e2122.

Luthra R., Platt L., Salamońska J. (2018). Types of Migration: The Motivations, Composition, and Early Integration Patterns of ‘New Migrants’ in Europe. International Migration Review 52(2): 368–403.

Łużniak-Piecha M., Golińska A., Czubińska G., Kulczyk J. (2018). Should We Stay or Should We Go? Poles in the UK during Brexit, in: M. Fleming (ed.), Brexit and Polonia: Challenges Facing the Polish Community during the Process of Britain Leaving the European Union, pp. 83–104. London: PUNO Press – The Polish University Abroad.

McGhee D., Heath S., Trevena P. (2012). Dignity, Happiness and Being Able to Live a ‘Normal Life’ in the UK: An Examination of Post-Accession Polish Migrants’ Transnational Autobiographical Fields. Social Identities 18(6): 711–727.

McGhee D., Moreh C., Vlachantoni A. (2017). An ‘Undeliberate Determinacy’? The Changing Migration Strategies of Polish Migrants in the UK in Times of Brexit. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43(13): 2109–2130.

Milewski M., Ruszczak-Żbikowska J. (2008). Motywacje do wyjazdu, praca, więzi społeczne i plany na przyszłość polskich migrantów przebywających w Wielkiej Brytanii i Irlandii. Centre of Migration Research Working Paper No. 35. Warsaw: University of Warsaw.

Moriarty E., Wickham J., Salomońska J., Krings T., Bobek A. (2010). Putting Work Back in Mobilities: Migrant Careers and Aspirations, paper given to the New Migrations, New Challenges Conference, Trinity College Dublin, 29 June – 3 July 2010.

Okólski M., Salt J. (2014). Polish Emigration to the UK after 2004: Why Did So Many Come? Central and Eastern European Migration Review 3(2): 11–37.

ONS (2018). Annual Population Survey Estimates of Lithuania and Poland Born and Nationals Resident in the UK, By Age Group, 2000 to 2017. London: Office for National Statistics. Online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigrati... (accessed: 26 May 2020).

ONS (2019). Migration Statistics Quarterly Report. London: Office for National Statistics. Online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigrati... (accessed: 26 May 2020).

Piętka-Nykaza E., McGhee D. (2017). EU Post-Accession Polish Migrants’ Trajectories and their Settlement Practices in Scotland. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43(9): 1417–1433.

Portes J. (2016). Immigration after Brexit. National Institute Economic Review 238(1): R13–R21.

Portes J., Forte G. (2017). The Economic Impact of Brexit-Induced Reductions in Migration. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33(1): S31–S44.

Radziwinowiczówna A., Kloc-Nowak W., Rosińska A. (2020). Envisaging Post-Brexit Immobility: Polish Migrants’ Care Intentions Concerning their Elderly Parents. Journal of Family Research, 9 March, doi: 10.20377/jfr-352.

Rodriguez M. L. (2010). Migration and a Quest for ‘Normalcy’. Polish Migrant Mothers and the Capitalization of Meritocratic Opportunities in the UK. Social Identities 16(3): 339–358.

Ryan L. (2015). Another Year and Another Year: Polish Migrants in London Extending the Stay Over Time. Kingston: Middlesex University Social Policy Research Centre.

Ryan L. (2018). Differentiated Embedding: Polish Migrants in London Negotiating Belonging Over Time. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44(2): 233–251.

Ryan L., Sales R. (2013). Family Migration: The Role of Children and Education in Family Decision-Making Strategies of Polish Migrants in London. International Migration 51(2): 90–103.

Rzepnikowska A. (2019). Racism and Xenophobia Experienced by Polish Migrants in the UK before and after Brexit Vote. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45(1): 61–77.

Salamońska J. (2012). Migracje i czas: młodzi Polacy w Irlandii w świetle jakościowego badania panelowego. Studia Migracyjne: Przegląd Polonijny 38(3): 111–132.

Salamońska J. (2017). Multiple Migration – Researching the Multiple Temporalities and Spatialities of Migration. Centre of Migration Research Working Paper No. 102. Warsaw: University of Warsaw.

Szewczyk A. (2016). Polish Graduates and British Citizenship: Amplification of the Potential Mobility Dynamics beyond Europe. Mobilities 11(3): 362–381.

Trevena P. (2013). Why Do Highly Educated Migrants go for Low-Skilled Jobs? A Case Study of Polish Graduates Working in London, in: B. Glorius, I. Grabowska-Lusińska, A. Kuvik (eds), Mobility in Transition. Migration Patterns after EU Enlargement, pp. 169–190. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Trevena P. (2014). Szkolnictwo a ‘sprawa migrancka’: percepcje angielskiego a polskiego systemu edukacyjnego i ich wpływ na decyzje migracyjne. Studia BAS 40(4); 105–133.

White A. (2010). Polish Families and Migration since EU Accession. Bristol: Policy Press.

Annex

Table A1. Detailed statistics; numbers and percentages

Source: CMR (2018) survey; N = 472.

Table A2. Detailed statistics; numbers and percentages

Source: CMR (2018) survey; N = 472.

Table A3. Summary statistics for the response variable and demographic variables included in all models

Source: CMR (2018) survey; N = 472.

Table A4. Summary statistics for the non-economic integration indicators included in Model 2

Source: CMR (2018) survey; N = 472.

Table A5. Summary statistics for the economic integration indicators included in Model 3

Source: CMR (2018) survey; N = 472.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.