Enhancing the Relative Acculturation Extended Model: A Qualitative Perspective

-

Author(s):Klakla, Jan B.Szydłowska-Klakla, PaulinaNavas, MarisolPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. , No. online first, 2025, pp. 1-19DOI: 10.54667/ceemr.2025.07Received:

1 July 2024

Accepted:21 March 2025

Published:23 April 2025

Views: 1061

Drawing upon insights from 2 empirical qualitative studies conducted within the framework of the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM), this paper proposes modifications to the model to better suit qualitative research inquiries into migrant acculturation experiences. Firstly, it highlights the interconnectedness of various psychosocial domains in migrants’ lives. Secondly, it challenges the distinction between public and private domains embedded in the model, arguing instead for an approach that recognises the dual nature of each domain, encompassing both public and private aspects. Thirdly, the authors suggest integrating values as transversal elements present across all domains, rather than treating them as a separate domain. These 3 specific modifications allow for a more nuanced understanding of acculturation processes, enabling researchers to capture the complexity of migrants’ experiences more comprehensively than the original version of the model. By emphasising flexibility and adaptability, the enhanced RAEM provides a useful framework for qualitative investigations into acculturation phenomena, facilitating deeper insights into the lived realities of migrant populations.

Introduction

This article focuses on the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM), which has primarily been utilised in quantitative research on the acculturation process of migrants in Spain (Cuadrado, García-Ael, Molero, Recio and Pérez-Garín 2021; López-Rodríguez, Bottura, Navas and Mancini 2014; Navas, García, Rojas, Pumares and Cuadrado 2006; Navas, García, Sánchez, Rojas, Pumares and Fernández 2005; Navas, Pumares, Sánchez, García, Rojas, Cuadrado, Asensio and Fernández 2004; Navas and Rojas 2010; Navas, Rojas, García and Pumares 2007; Rojas, Navas, Sayans-Jiménez and Cuadrado 2014) and Italy (Mancini and Bottura 2014). Our objective is to propose modifications to the model’s structure based on the results of our 2 empirical research projects, aiming to facilitate its application in qualitative research. Initially, we provide an introduction describing definitions of immigration, acculturation and dual identity and a succinct overview of the original model. Subsequently, we outline the research supporting our proposed modifications. In the main body of the paper, we delineate potential adjustments pertaining to the model’s structure. We challenge the rigid categorisation into central and peripheral (private and public) domains, advocating instead for integrating both public and private aspects of acculturation experiences within each RAEM domain. Within the domains themselves, we scrutinise their separability and question the relevance of delineating the values domain as distinct.

Our paper represents the inaugural endeavour to comprehensively adapt a model widely utilised in quantitative acculturation research for application within a qualitative paradigm. Furthermore, it constitutes an effort grounded in empirical research, affirming the efficacy of the modified RAEM as a qualitative research tool and analytical framework.

Theoretical background

Acculturation in the context of global migration

One of the great social challenges of the 21st century is undoubtedly the international migratory movement and the impact it produces on both migrants and the societies that receive them. Although migrations have always occurred and have been key to the development and evolution of human beings, never before in the history of mankind has there been a period in which so many people have lived outside their countries of origin. This number was estimated to be 281 million in 2020 (3.6 per cent of the world population; McAuliffe and Triandafyllidou 2021). These movements have a major impact on different areas (e.g., political, economic, social, psychological) of the lives of displaced persons and of the societies in which they arrive, generating great diversity (ethnic, cultural, religious, etc.) but also enormous challenges of adaptation and mutual adjustment that can lead to problematic or conflictive intergroup relations.

One of the most important lines of psychosocial research in the field of migration has been the study of the acculturation and identification processes experienced by migrants and the relationship these processes have with their adaptation in receiving societies (for a review, see, e.g., Brown and Zagefka 2011; Sam and Berry 2016; Schwartz and Unger 2017).

Acculturation refers to the process of cultural transformations that occur when 2 or more culturally distinct groups come into contact. This is the classic definition provided by Social Anthropology and Sociology, the first disciplines to address this process in the North American context (see, e.g., the definition by Redfield, Linton and Herskovits 1936). However, acculturation also refers to the changes experienced by individuals (‘psychological acculturation’) in cognitive, affective and behavioural aspects (e.g., attitudes, values, behaviours and identity), as a consequence of continuous and direct contact with people from diverse cultures (Berry 1997; Graves 1967). The way in which the acculturation process is resolved will have important consequences on the adaptation (psychological and sociocultural) of people to their own culture (Searle and Ward 1990; Ward and Kennedy 1993).

The literature has shown that the acculturation process involves all groups in contact; it is a reciprocal process, with consequences for all parties. All groups in contact change the minorities and majorities that make up the host societies (Berry 1997; Bourhis, Moïse, Perreault and Senécal 1997), although these changes occur more intensely in the arriving minorities. Often, migrants are not completely free to choose how to resolve the acculturation process, because they are largely dependent on the attitudes that receiving societies have towards them and the immigration policies that are implemented (Sam and Berry 2010). Receiving societies and their contexts (social, political, economic, etc.) play a fundamental role in these processes, facilitating or hindering certain forms of acculturation and, therefore, of the adaptation of migrants (Berry 2023).

In contrast to the first unidimensional models (e.g., Gordon 1964), current psychological acculturation models (e.g., Berry 1997; Bourhis et al. 1997; Navas et al. 2005) consider 2 independent attitudinal dimensions on which migrants and the host society can stand: a dimension of maintaining the culture of origin (To what extent do I consider it important and valuable to maintain my culture of origin or my identity in this new society?) and a dimension of adopting the host culture (To what extent do I consider it important and valuable to adopt elements of the host culture?). The combination of these 2 dimensions gives rise to 4 ways of resolving the acculturation process and 4 options (strategies/preferences) of acculturation: integration, assimilation, separation and marginalisation.

Different identities (e.g., ethnic, cultural, ethnocultural, national, religious) constitute central aspects in the process and definitions of acculturation (Phinney and Alipuria 1990, Phinney, Horenczyk, Liebkind and Vedder 2001). According to Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner 1979), social identity is the sense of self that people derive from their membership in social groups. Specifically, a person’s social identity includes ‘knowledge of his or her membership in a social group (or groups), together with the valuational and emotional meaning associated with that membership’ (Tajfel 1984: 292). The formation and maintenance of a positive social identity is crucial to the development of a positive self-concept and self-esteem and shapes how individuals perceive themselves and interact within social groups.

Based on this definition, ethnic identity refers to the sense of belonging to a particular ethnic group. It can encompass several aspects such as self-identification, feelings of belonging and commitment to the group, as well as shared values and attitudes towards one’s own ethnic group (Liebkind, Mähönen, Varjonen and Jasinskaja-Lahti 2018). Another essential part of the social identity of people settling in a new host society is national identity, defined as self-categorisation and emotional attachment towards the national majority or host society (Liebkind et al. 2018). In the psychosocial literature, ethnic and national identity are used as an operationalisation of cultural identity, especially when analysing populations of children and youth with immigrant backgrounds (Maehler, Daikeler, Ramos, Husson and Nguyen 2021). Both identities are considered independent of each other. That is, individuals can identify with their ethnocultural group (ethnic identity) and with the host country – or the country in which they grew up (national identity) – without involving any conceptual or empirical contradiction (Berry and Sabatier 2010; Zhang, Verkuyten and Weesie 2018). When people are strongly identified with both groups (ethnic and national), the literature points out that they present a dual, bicultural, multicultural or integrated identity (Fleischmann and Verkuyten 2016; Maehler et al. 2021; Phinney 2003). Ethnic and national identity, together with acculturation strategies and preferences, are key variables for understanding, from an intergroup perspective, how people of immigrant origin and those of the host society manage coexistence with diverse cultural groups.

About the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM)

The Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM – Navas et al. 2004) originated from the University of Almeria, situated in the ethnically diverse province in southern Spain. Its development aimed to enhance the understanding of intergroup relations within the province, with the ultimate goal of designing tailored social interventions for the local community (Navas and Rojas 2010). The RAEM posits that migrants may adopt multiple acculturation orientations simultaneously across various domains of life (as defined in Berry’s model (1997): integration, separation, assimilation and marginalisation). These are known as domains of acculturation, including in peripheral (also referred to as public) areas: political, social welfare, work and economy; in central (also referred as private) areas: social relations, family relations, religion and values for adults; and in the case of adolescents in peripheral areas – school and the economy – and in central areas such as social relations, family relations, religion and values (López-Rodríguez et al. 2014; Mancini and Bottura 2014).

Research on the acculturation process, including studies utilising RAEM, consistently demonstrates that the extent of adoption of the majority culture is more pronounced in public domains, such as the realm of employment. Conversely, in private domains, such as family dynamics, a greater retention of the culture of the country of origin is often observed (Arends-Tóth and van de Vijver 2004; Birman and Simon 2014; Rojas et al., 2014). Additionally, migrants’ acculturation orientations are situated within 2 dimensions: the real plane and the ideal plane. The real plane signifies the orientations actually manifested by migrants. In contrast, the ideal plane represents the orientations preferred by migrants, reflecting what they would ideally like to achieve under optimal conditions. Similarly, concerning the host society, a distinction can be made between the real plane – comprising the orientations perceived by the host society as actually being realised by migrants – and the ideal plane, representing the preferences regarding the orientations that migrants should ideally adopt. In both the newcomer group and the host society, these 2 dimensions may align or exhibit significant disparities.

Acculturation is not viewed as a unilateral process; rather, it entails changes not only in migrants’ cultural patterns but also in those of the host society. The RAEM, akin to other models (Bourhis et al. 1997), acknowledges the diverse intergroup relations that emerge from the intersection between the preferences of the host society towards the acculturation orientation of migrants and the actual orientations put in practice or preferred by migrants – whether they be consensual, problematic or conflictual.

Research conducted utilising the model should acknowledge the ethnic and cultural diversity within migrant groups and consider the various psychosocial factors external to the model. These factors may include in-group bias, identification with one’s own group, perceived cultural enrichment, stereotypes and prejudices against specific groups, perceived similarities, intra- and intergroup differentiation, intergroup contact and collectivism (Navas et al. 2005, 2007).

The features of the model discussed above can also be observed in Figure 1, which shows the acculturation process in a simplified but clear way, as captured by the Relative Acculturation Extended Model envisioned by its creators. Such a nuanced approach renders the model valuable for research conducted across disciplines and research paradigms. However, it is worth noting that not all of the aforementioned assumptions are fully integrated into the model in the most optimal manner for qualitative research purposes.

Our choice of the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM) was not incidental. RAEM is one of the most widely used extensions of Berry’s classical acculturation model (see Sam 2024), making it a well-established framework within acculturation studies. While Berry’s model provides a foundational understanding of acculturation strategies, RAEM offers a more nuanced perspective which allows for a more context-sensitive analysis of acculturative processes. This added complexity makes it a strong starting point for adaptation to qualitative research, where a more flexible and dynamic approach to acculturation is needed.

Figure 1. Relative Acculturation Extended Model

Source: Own elaboration based on Navas and Rojas (2010).

Note: The middle column shows the effect of the acculturation process of migrants in various spheres of life. The blue colour represents the extent to which migrants maintain their culture of origin and the orange colour represents the extent to which migrants adopt the culture of the country of emigration in each sphere of life described in the RAEM.

Research using the RAEM

Studies utilising this model with migrant and native people have predominantly employed the RAEM questionnaire (Cuadrado, García-Ael, Molero, Recio and Pérez-Garín 2021; López-Rodríguez et al. 2014; Navas and Rojas 2010; Navas et al. 2004). The survey’s migrant respondents, through a self-reported scale, assess the degree to which they maintain their own culture within each acculturation domain (e.g., political, social welfare, work, economy, social relations, family relations, religion and values) and the extent to which they adopt the culture of the host country. This assessment is typically conducted using a 5-point scale, where 1 signifies ‘none’ and 5 signifies ‘very much’.

Respondents do not provide information pertaining to the specific experiences (behaviours, motivations, attitudes, emotions) constituting acculturation within a particular domain. Instead, they offer a general assessment of their status within those domains. Consequently, migrants may only report actions and beliefs of which they are aware or those which they consciously choose to disclose to the interviewer. Moreover, it is contentious to assume that the acculturation process is entirely transparent to the migrant and that s/he possesses comprehensive self-awareness regarding its course. Setting aside considerations of the self-awareness of desires and motivations, it is important to recognise that individuals may not have a complete understanding of their own behaviour, especially when quantifying it. For instance, migrants may not have full awareness of the structure of their social circles or the proportion of language they use in daily activities. Ultimately, quantitative research utilising both the RAEM and other models like Berry’s orthogonal one (Berry 1990), does not elucidate the specific set of behaviours and experiences which a participant has in mind when assessing each domain.

However, it is noteworthy that the authors of the RAEM (Navas et al. 2004) also employed qualitative methodology during the model testing phase and in a few subsequent research endeavours. The study with survey methodology (Navas et al. 2004) was complemented by focus-group and narrative-biographical interviews, which were subsequently analysed, among other approaches, utilising a theoretical framework grounded in the RAEM.

The utilisation of qualitative methodology in research conducted by Pumares, Navas and Sánchez (2007) facilitated the exploration of topics pertinent to the acculturation process that are prioritised by representatives of diverse social institutions working with immigrants in Almería, as well as their perceptions of the most pressing issues. It also enabled the identification of native expectations regarding strategies put in practice for migrants within specific domains of acculturation. Additionally, the results of qualitative analyses from another project indicate that immigrant families employ a variety of acculturation orientations and that there exist conflicting expectations between the home and social environments regarding the acculturation strategies undertaken by immigrant children (Navas and Rojas 2019).

There are limited studies that scrutinise the RAEM within the realm of qualitative analysis. Barbara Thelamour’s studies (Thelamour 2017; Thelamour and Mwangi 2021) investigating the perceptions and preferences of hosts (Americans of American descent) towards acculturation strategies undertaken by immigrants from Africa (of non-American descent) employed both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Thelamour’s approach allowed participants to articulate their thoughts on the acculturation of African immigrants and to define Black American culture, thereby elucidating differences in acculturation resulting from participants’ conceptualisations of their host culture. It is noteworthy that Thelamour utilised definitions of life domains different from those in the original RAEM, tailored to her research group. Additionally, she highlights the necessity for more-targeted qualitative questions based on the RAEM to validate survey responses. Monika Ben-Mrad (2018) conducted qualitative research, utilising this model, with Turkish residents of Polish descent. The findings of her study reveal that, among the group of Polish expatriates living in Istanbul, respondents frequently discuss strategies associated with assimilating into the new culture in the public domain, while maintaining aspects of their own culture in the private domain. However, the authors of the aforementioned research did not prioritise describing the resultant reflections on the model itself.

Description of the studies from which the model modifications are derived

Our reflections on the Relative Acculturation Extended Model stem from our own research experience in conducting qualitative studies using this framework. In the next section, we provide a succinct overview of the qualitative research strategy employed in each of our studies, along with the methods utilised for data collection and analysis.

Study 1. Conducted with children and their parents of Polish origin residing in Spain (principal investigator: Paulina Szydłowska-Klakla)

The study employed a qualitative research approach utilising a field research strategy, which encompassed observations and multiple case studies (Yin 2018). Each case study focused on a parent-child pair of Polish origin residing in Spain, with a total of 21 cases examined. Data collection involved semi-structured interviews conducted separately with both the children and their parents. For the children, additional visual methods such as pictures and drawings were utilised. The collected data underwent analysis using the template analysis method (King 2012; Langdridge 2007). Template analysis, rooted in interpretative-phenomenological analysis, is a method commonly employed in qualitative psychological research to explore experiences (Smith 2017), with a stronger emphasis on referencing existing theoretical knowledge (Brooks, McCluskey, Turley and King 2015). Both the interview guides and the analysis template were constructed based on the RAEM framework. The coding process was conducted in MAXQDA using an initial template based on the RAEM, which included a predefined set of codes. As the analysis progressed, new codes emerged reflecting participants’ life experiences and were organised into broader categories such as ‘grief’, ‘discrimination’ or ‘ethnic identity’. This dual approach enabled the identification of behaviours and experiences linked to acculturation orientations. At the same time, it allowed for the discovery of new codes related to key life circumstances related to acculturation. These emerging themes, tied to participants’ developmental contexts and goals, provided a deeper understanding of the acculturation process beyond the original framework of the model. Reflecting on the research process, the main researcher recognised the value of her fluency in Spanish and her 16-month stay in Spain. These factors were crucial for data interpretation and interviews, as many children preferred speaking Spanish over Polish and the parents Polish over Spanish.

Study 2. Focusing on legal and institutional factors in the acculturation process of Slavic migrants in Poland (principal investigator: Jan Bazyli Klakla)

The second empirical research study, serving as the foundation for this work, involved conducting 5 expert interviews with migration professionals and 15 biographical-narrative interviews with migrants from European Slavic countries who arrived in Poland between 1989 and 2010. In the analysis, the Template Analysis method (King 2012; Langdridge 2007), biographical analysis (Schütze 2012) and the formal-dogmatic method were employed. Like Study 1, the interview guides and initial analysis templates were structured based on the RAEM framework. The data collected during the empirical research were organised according to identified themes such as citizenship, the labour market, street-level bureaucracy, education, discrimination, healthcare and Polish ancestry (for the full study, see Klakla 2024).

The reflection on the model and the process of developing its modifications followed a similar trajectory in both studies. The original version of the RAEM served as a starting point, guiding the research design, the development of research tools and the initial stages of analysis. However, as the qualitative analysis deepened, certain aspects of the model appeared less compatible with the nuanced nature of qualitative inquiry. This led to proposals for modifications aimed at increasing the model’s flexibility and applicability. In Study 2, the revised model was then tested against the collected data, allowing for further refinement. Through this iterative process, we arrived at the version of the RAEM presented in this article. Both research projects were conducted in parallel at the same university, with continuous exchange and consultation between the authors. Experts from the Centre for Migration Studies in Almería were consulted during that process, ensuring a rigorous and reflective approach to model development.

Ethical considerations

Both studies complied with ethical guidelines for psychological research (American Psychological Association 2017). Participants were informed about the study’s purpose, data anonymisation and their right to withdraw at any time. Adult participants provided written or verbal informed consent for their own participation and, in Study 1, for their child’s involvement, including the recording and transcription of interviews. Additionally, in Study 1, children gave verbal consent, while adolescents over 16 signed written consent forms.

Results – proposed modifications

As a result of the aforementioned studies, two sets of recommendations for potential modifications of the RAEM for qualitative research have emerged: recommendations on model content and recommendations on model structure. Model-content modifications pertain to the definition of culture used in the model and the influence of life circumstances and psychosocial context on the acculturation process. Model-structure modifications involve model assumptions and its construction. These proposals are grounded in the conclusions drawn from the data analysis process in both research projects. Therefore, they should be viewed as sources of inspiration rather than rigid modifications, as the contextual conditions and life circumstances may vary between different study groups. In this text, we present proposals concerning elements of the model structure, which stem from significant aspects related to the participants’ experiences of acculturation. We substantiate our proposals with examples of statements made by the respondents.

It is important to note that applying the model to research involving different migrant groups or in diverse cultural contexts may yield new insights and perspectives.

Overlap of domains

The first proposed change pertains to challenging the assumption that the domains of psychosocial functioning of migrants, as defined by the model’s creators, are non-overlapping. While this assumption proves useful in survey techniques where each domain is allocated a specific set of questions in the questionnaire, it presents a limitation when analysing qualitative data. In qualitative analysis, this division appears artificial and purely analytical, obscuring rather than elucidating the acculturation process. Our qualitative research, encompassing both Study 1 and Study 2, revealed that the phenomenon of intersection among 2 or more domains is prevalent.

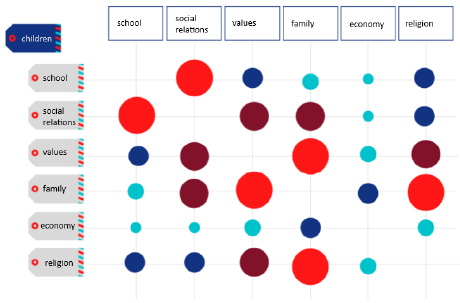

Figure 2. Visualisation of a section of the code tree on acculturation domains according to the RAEM in a group of children

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The utilisation of multiple case-study or biographical-narrative research strategies, coupled with the consideration of context, enabled us to discern individual acculturation experiences showcasing a multitude of strategies in both the real and ideal planes, sometimes within a single domain and even for a single person. During the qualitative data analysis, we observed that life domains overlap, as illustrated in Figure 2 – which presents a visualisation of the relationships between codes in the code tree within Study 1. The diagram depicts categories resulting from the RAEM in the context of children’s functioning. It illustrates how frequently given statements were coded with more than one category of code (the size of the circle indicates the frequency of coding with the same categories for a given statement). Many experiences are associated with more than one domain; for instance, attending a semi-private Catholic school can be interpreted within the domains of both school and religion. Similarly, buying Polish products in a Polish grocery store may be interpreted within the domains of family or economics. Among children, the most common overlap occurs between school and social relations, followed by family and religion or family and values. Examples of these overlaps are described below the diagram. Both the size (from smallest to largest) and the colour (from blue to red) correspond to the number of text segments coded with both a code from the category represented in the rows and a code from the category represented in the columns.

The first example (school and social relations) appears quite natural, given that the peer environment is significantly influenced by both Polish1 and Spanish schools. Below is an illustration exemplifying how a Spanish-born child upholds Polish culture and shares it with her peers. This may suggest institutional support from the school, which aids the child in preserving her parents’ cultural heritage.

Yes, I really enjoy speaking Polish and I do so regularly. I’ve been teaching my friends for 5 years now. I’ve taught them Polish songs. My friends Maria and Alba are going to Poland soon and we plan to spend time there together (Linda, 12 years old, Study 1).

This statement illustrates the adoption of an integration orientation within both the school and the social-relations domains. Despite not attending a Polish school, Linda effectively preserves her parental cultural heritage. A developmental theory reflecting a similar assumption regarding overlapping life domains is Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory, which posits the coexistence of multiple systems at different levels. Birman and Simon (2014) underscore that delineating life domains in acculturation analysis enables contextual consideration, aiding in understanding why individuals adopt varied strategies across different life domains. However, assuming acculturation occurs across microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem, individuals do not acculturate solely within isolated domains.2 Instead, life domains intermingle and mutually influence each other, contributing to the complexity of experiences between domains as well as within domains themselves (including the public and private aspects of experience, as discussed in the following section). The statement below also exemplifies this complexity, encompassing themes related to the economic domain, family relations and employment.

I finished school and started looking for a job. However, the wages for a medical caregiver are low, the workload is heavy and my husband disagreed. He said, ‘No, you won’t do it’ and that was the end of it. So, I did some occasional cleaning work until 2015 (Olena, Study 2).

Instances of overlap between domains can also highlight significant emergent elements of the acculturation process. For example, discrimination often occurs in both the school/labour and social-relations domains, while illness may affect the family and social-security domains. Additionally, power distance can be observed across family, social relations and school domains, while aspects like food and leisure activities are relevant to economics, family, religion and social relations. These intersections suggest that at the nexus of domains lie categories of experience directly reflective of the subjects’ lived realities.

Public and private aspects of acculturation experiences inside RAEM domains

The authors of the RAEM originally classified the domains as peripheral and central or, alternatively, as public and private. In this discussion, we utilise the latter distinction because, from our perspective, it more accurately captures the features of these domains and carries fewer ethnocentric connotations, as highlighted in acculturation research by scholars such as Rudmin, Wang and de Castro (2016), among others. The terms ‘public’ and ‘private’ better convey the essence of these domains, avoiding implications of inferiority or hierarchy inherent in the terms ‘central’ and ‘peripheral’.

The public domains encompass politics, social well-being, labour and economics, while the private domains comprise social relations, family relations, religion and values. As previously mentioned, when outlining the model, this division is grounded in the distinct trajectories of acculturation observed in the public and private domains (Arends-Tóth and van de Vijver 2004; Birman and Simon 2014; Rojas et al. 2014).

The theoretical underpinning of this division is not fully disclosed by the RAEM creators. We believe that it can be elucidated by drawing from sociology, specifically the conceptualisation of public and private domains articulated by scholars such as Sheller and Urry (2003). According to this perspective, private areas are those that the bourgeoisie sought to shield from state interference (Habermas 1989), thereby affording a certain degree of freedom of choice. For instance, while individuals generally lack the autonomy to dictate whether their workplace should employ migrants due to anti-discrimination laws, they retain the freedom to choose their social interactions outside of work (Haugen and Kunst 2017). A similar dynamic applies from the perspective of minority groups. For migrants, particularly those arriving, with their families, in a new country, cultural preservation typically occurs within the confines of the family home, constituting a private sphere. In contrast, the acquisition and learning of culture are predominantly driven by necessity within the public domain (Boski 2008).

Drawing from this theoretical framework and considering the insights gleaned from our qualitative research conducted with the RAEM, it becomes evident that the individual domains of psychosocial functioning among migrants do not exclusively possess a public or private character. Instead, each domain encompasses both public and private aspects, albeit in varying proportions.

In the realm of social relations, for instance, we encounter both work colleagues and close friends. Similarly, the economic domain encompasses not only household expenses and home-cooked meals but also expenditure related to public activities such as cinemas, swimming pools and concerts. Even in religion, typically perceived as a deeply private domain, there exist certain public manifestations, such as attending a church or mosque, participating in religious lessons at school or wearing religious symbols in public. Hence, we advocate for a more flexible approach in qualitative research, suggesting the analysis of each domain in terms of its public and private facets rather than rigidly classifying them as inherently public or private.

During interviews with respondents, it became evident that numerous private elements emerged in statements traditionally classified as pertaining to public domains, based on previous studies employing the model. Conversely, elements associated with public aspects of life surfaced within private domains, particularly in the realm of religion and social relations. This observation prompted us to contemplate the notion that experiences of both a public (peripheral) and a private (central) nature can manifest within any domain.

In this context, Dragan (Study 2) elucidates the significance of performing certain religious practices in public for the preservation of Serbian identity among migrants:

Specific aspects of identity and unique Serbian cultural threads are intricately linked to religion. Without these elements, Serbian culture would lack its distinctive essence. Take, for instance, the patron saint holiday. If this tradition were absent, Serbians would not truly embody their identity. Even Serbians who converted to other religions, such as Islam, continued to observe the patron saint’s feast, despite no longer identifying as Christians. Hence, from this perspective, it’s nearly impossible to dissociate oneself from religion.

The dynamics of change in these two aspects of the domain of religion – public/peripheral and private/central – can vary significantly. Someone may preserve culinary customs at home while also enjoying meals at local restaurants with friends; they may form close friendships primarily within their own cultural or religious group but also establish relationships, including romantic ones, with members of the host society. Similarly, individuals might choose to avoid displaying their religious identity in public spaces while actively practicing their faith in private settings, such as at home.

At the same time, while religious identity is often associated with the private sphere, it can also be manifest in public aspects of life. Participation in religious ceremonies, attending services at places of worship or engaging in religious community events can serve as public expressions of one’s faith. In this way, the boundaries between private and public expressions of religion are fluid, shaped by personal choices, social norms and contextual factors.

The following experience serves as another illustration of a similar scenario, showcasing the adoption of separation strategies in the domain of social relations. This behaviour may stem from Zosia’s recent arrival in Spain and her ongoing acclimatisation to new cultural norms. Zosia’s encounter with the unfamiliar practice of hugging strangers, particularly among adults, underscores her discomfort with the perceived invasion of personal space – a manifestation of separation that pertains to the private aspect within the implicitly public domain of social relations:

In Spain, even if you don’t know the person, they just hug you. Maybe children hug but adults, for instance, one kisses on the cheek and the other... but honestly, I don’t know, it’s a little strange... But I suppose you get used to it, so it’s considered completely normal (Zosia, 12 years old, Study 1).

The domains originally delineated in the RAEM as private (social relations, family relations, values and religion) also encompass public aspects, wherein experiences indicative of an assimilation strategy transpire. Private experiences within these domains pertain to rules, values, and home life, while public aspects encompass leisure activities, social interactions in public spaces, and participation in public religious events. The mother of 13-year-old Adam (Study 1) sheds light on this topic:

My husband sleeps a lot. We’ve already adapted to the Spanish system here so, after lunch, it’s ‘siesta’ time. We often tune in to the Polonia channel; for instance, we watch ‘Father Matthew’ on Tuesdays. [Interviewer: So, you already have such rituals.] Yes, indeed. We, as a family, enjoy it. For example, we watch ‘Father Matthew’ while having our meal.

The initial segment of the quote illustrates experiences indicative of an assimilation strategy within the family domain, particularly in the context of leisure activities. The reference to a ‘siesta’ denotes an after-lunch nap, commonly associated with Spanish culture. Here, the family adopts elements of Spanish culture related to leisure and communication, as they converse in Spanish at home. Simultaneously, Polish traditions remain strongly upheld in aspects such as communal meals, holiday celebrations and religious observances, indicating a strategy of separation and the inherently more private nature of these facets of life. Taken together, it suggests that this family is pursuing an integration strategy within the private realm of family life.

This modification provides a deeper understanding of acculturation by highlighting that each domain of life encompasses both a public/peripheral aspect – where assimilation and integration experiences predominantly occur – and a private/central aspect, where separation and preservation experiences tend to prevail. Recognising this complexity serves as a guideline for future research, as it challenges the simplistic classification of domains as purely private or public (Arends-Tóth and van de Vijver 2004; Navas et al. 2005; Phalet and Swyngedouw 2003). This nuanced understanding acknowledges the dynamic interplay between assimilation, separation, integration and marginalisation orientations across various aspects of migrants’ lives, fostering a more comprehensive analysis of the acculturation process.

Values as a transversal domain

The inclusion of ‘values’ as one of the domains of the psychosocial functioning of migrants needs an in-depth consideration. However, characterising this domain as proposed by the creators of the RAEM (i.e., placing it on a par with other domains such as work or family), is valid only if we assume its ontological equivalence with these other domains. Values can be treated as a separate domain only if we adopt the theory of objective values, which posits that certain objects possess intrinsic value (e.g., Platonic ideas such as goodness or beauty), while others do not. In this framework, it becomes possible to construct a closed catalogue of values applicable to every migrant and member of the host society, allowing the domain of values to function within the model alongside other domains, encompassing a distinct yet interconnected fragment of social life.

In quantitative research conducted based on the RAEM, all the distinguished domains are treated as separate entities with equal status, each having a specific set of questions in the questionnaire. However, we argue that the inclusion of values within this model can be theoretically justified only if an objective theory of values is adopted. Conversely, qualitative research conducted using the model suggests that a different approach may be more appropriate. To elucidate this point, we will draw upon Krzysztof Pałecki’s (2013) concept of values and Shalom Schwartz’s (2012) definition of values, although our considerations can be applied to most theories of values that do not assume their objective nature. Let us endeavour to comprehend the nature of values and discern what sets them apart from elements found within other domains of migrants’ psychosocial functioning, such as family dynamics or economic activities.

Values, as delineated by Pałecki, are essentially effects, objects and/or states of affairs desired by individuals. In Pałecki’s framework (2013), a value exists strictly when there is a perceptual relation between a particular subject and any object perceived by them, characterised by at least a minimal and tangible emotional response, known as ‘aplusia’. Aplusia denotes a specific positive feeling encompassing attraction to, desire for, spontaneous acceptance of or satisfaction with the existence of a perceived object – or joy derived from its perception. Positioned within the discourse on the existence of values independent of human cognition, this concept aligns with moderate non-cognitivism. It disavows the existence of objective values, as these latter are always contingent upon someone’s desires. However, it acknowledges the empirical demonstration that an object or state of affairs holds value within a specific social group. When a value is universally felt or endorsed by a significant portion of a given collective, it is qualified as a social value.

Operating under this assumption, values can manifest in various domains of social life, without necessarily constituting a distinct, stand-alone area. For instance, migrants may perceive a positive relationship with their boss at work as a value, which would fall within the professional/work domain. Additionally, they may value honesty in interpersonal interactions, pertaining to the social relations domain – or democracy, associated with the political domain. Furthermore, certain consumer goods or money itself may also be perceived as values within the economic domain.

Moreover, values encompass both an ideal plane and a real plane. The ideal plane refers to the deeply internalised, lived values that genuinely guide an individual’s attitudes and behaviours. In contrast, the real plane pertains to the explicit statements which people make about values, which may not always align with their actual lived experiences. This distinction allows for the recognition of a potential gap between declared values – which might be shaped by social expectations, norms or aspirational self-perception – and real values, which are authentically reflected in one’s actions and decisions. Understanding this discrepancy is crucial for analysing value systems, as individuals may consciously or unconsciously express adherence to certain values which, in practice, do not fully shape their lived reality.

Hence, we advocate for treating values as cross-cutting and intersectional levels of analysis, rather than as a distinct domain of migrants’ psychosocial functioning. An empirical illustration of this nature of values is evident in Natallia’s statement, where participating in elections and fulfilling her ‘civic duty’ is regarded as a value. This activity can be situated within the domain of politics.

I care very much, that even when I didn’t want to and I was saying that maybe I won’t go, my friends said: ‘How can you, after all, they gave you this citizenship for something’. So my friends from Belarus themselves, who also already have citizenship, were saying: ‘How can you say that, you should go and take a selfie, show that you were there and voted’ (Natallia, Study 2).

To support this modification of the model from a psychological standpoint, Schwartz’s definition of values can be utilised as an alternative to Pałecki’s concept (Schwartz 2012). According to Schwartz, values are cognitive representations or beliefs of motivational, desirable, supra-situational goals. These goals are significant as they drive our behaviour (what we do), justify our past actions (why we did them), guide our attention (what we notice) and serve as standards for evaluating people and events (who and what we like or dislike) (Schwartz 2006). Schwartz underscores the motivational aspect of values, emphasising that values themselves are defined by desirable goals that prompt action. Additionally, the transcendent nature of certain situations is pivotal in this characterisation of values.

Like Pałecki’s perspective, Schwartz acknowledges that values can be subjective rather than objective. They represent desirable states of affairs for individuals, defined by them and subject to variation depending on the situation and developmental stage. In the case of children, values are largely influenced by those transmitted through the socialisation process by parents and the surrounding environment.

Using Schwartz’s theory of values as an extension of the RAEM, as well as broader research on the acculturation process, it can be argued that behaviour motivated by values and characterised by an emotional connection to the object, can manifest itself in both the private and public aspects of any domain. In the RAEM questionnaire for young people, values are defined as ‘friendship, companionship, respect for the elderly, equality between men and women, the role of religion in your life, etc.’. Once again, this observation highlights that all these elements are integral parts of other domains of acculturation. For instance, friendship and companionship are evident in the domains of family relations, social relations and school. Similarly, the role of religion in life is visible in the domains of economics, family relations and social relations. Respect for the elderly and equality between men and women can be observed in the domains of social relations, family and school. For example, Miłka’s statement illustrates how values such as respect for the elderly are manifested in social interactions within various domains:

You can see very much that they (Spanish adolescents) laugh at others or if some old lady says ‘Good morning’ they look at her badly. I want to say something but I tell her ‘Good morning’ and that’s it (Miłka, 14 years old, Study 1)

Therefore, these arguments also support a potential shift in the understanding of the domain of values in the study of the acculturation process using the RAEM, suggesting that it should be viewed as a transversal domain. This means that values are related to the motivation to take specific actions in the other domains of life proposed by the RAEM. Importantly, values should be interpreted from the bottom up, emerging from the data collected in a given study group.

Figure 3 is the diagram of the Relative Acculturation Extended Model after the modification incorporating values as a transversal domain. The change in the position of the values domain is visible in the diagram. In the original model (see Figure 1), it is placed below the other 7 domains whereas, in the modified version, it intersects all of them.

Figure 3. Relative Acculturation Extended Model after modification

Source: Own elaboration and Navas and Rojas (2010).

Indeed, our reflections can be extended to other domains, albeit under specific circumstances. For instance, religion may also serve as a transversal and intersectional level of analysis in certain communities where it deeply influences nearly every domain of social life. This is particularly evident in traditional Muslim communities or those associated with Buddhist monasticism. In such cases, the relationship between religion and other areas of migrants’ psychosocial functioning may mirror what we described regarding values.

Similarly, the domain of family can also play a transversal role during research with parents. This is because values associated with child-rearing significantly influence behaviours across various domains of life. Additionally, life circumstances such as illness can prioritise certain domains, such as social well-being and family, in the acculturation process. Therefore, considering these domains from a transversal perspective can provide valuable insights into the complex dynamics of the acculturation process among migrants.

Conclusions

Our variation of the Relative Acculturation Extended Model offers a more nuanced perspective on the acculturation of migrants through 3 key modifications. Firstly, it underscores the interconnectedness and interplay between psychosocial domains, recognising that they are not isolated but, rather, influence one another. This holistic approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of acculturation. Secondly, it introduces the concept that each psychosocial domain contains both public and private aspects, rather than being strictly labelled as private or public. This recognition allows for an appreciation of how the acculturation process may unfold differently in the private and public aspects of migrants’ lives within each domain. Lastly, our perspective emphasises the relational nature of values, positioning them as a transversal element present in every psychosocial domain. Rather than treating values as objective and separate, this approach acknowledges their role in shaping behaviours and experiences across various aspects of life. Moreover, in our study, as noted by other researchers (Liebkind et al. 2018; Phinney and Alipuria 1990; Phinney et al. 2001), identity development plays a crucial role in the acculturation process, closely linked to the values related, for example, with religion or the social relations which an individual adopts. Thus, distinguishing values as a transversal sphere within the model may be beneficial for future research in this field. Together, these modifications enhance the suitability of the RAEM for qualitative research, enabling a more in-depth exploration of the complexities of the acculturation experience among migrants.

The original Relative Acculturation Extended Model laid a robust groundwork for qualitative research by offering a holistic perspective on the acculturation process within the expansive framework of migrants’ lives. Its systemic approach enabled researchers to explore the intricate interconnections and interdependencies among different facets of migrants’ psychosocial functioning, thereby facilitating a more nuanced understanding of their experiences compared to less complex models like Berry’s two-dimensional framework (see Berry 1980; Berry and Sam 1997; Berry, Kim, Minde and Mok 1987).

Moreover, the adaptable nature of the RAEM model, conducive to adaptations and refinements, enhances its value for qualitative investigations. Through the introduction of modifications, such as those we have proposed, the model becomes even more accommodating to the unique intricacies of acculturation experiences among diverse migrant groups. Essentially, these adjustments amplify the model’s efficacy within the domain of qualitative research.

The proposed adaptations of and modifications to the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM) introduced in this article open new pathways for research and theoretical exploration, as well as for its application in capturing the complexity of the acculturation process across different populations (adults, adolescents, children). Acculturation is a deeply individualised process, shaped by a dynamic interplay of multiple factors within specific social contexts. Any attempt to model it must therefore balance the need for conceptual clarity with the inherent fluidity of lived experiences.

The way in which we configure an acculturation model is not just a technical choice; it reflects a broader understanding of how individuals engage with society and navigate cultural change. While the RAEM offers a structured framework, we acknowledge that certain research paradigms – especially those rooted in highly emergent, bottom-up methodologies – may still find its categories too rigid. However, rather than serving as a strict classificatory tool, the model can function as a reference point or heuristic device for scholars employing inductive approaches, such as grounded theory. At the same time, our modification of the RAEM is particularly well-suited for qualitative studies that incorporate some level of predefined categorisation, offering, for example, a template for template analysis, an initial guide for developing codebooks or a comparative lens for cross-case analysis. As more qualitative research is conducted using this model, we anticipate that further refinements and adjustments will enhance its flexibility, making it increasingly responsive to diverse methodological traditions.

Notes

- Most children and adolescents who took part in Study 1 attend Polish Saturday Schools in which they study the Polish language and Polish History and Culture.

- The microsystem, the closest layer to the child, encompasses direct interactions such as family or pre-school, impacting on behaviours like reliance, autonomy, cooperation and rivalry. The mesosystem, the second level, acknowledges that these microsystems are not isolated but interconnected, affecting one another. Acting as a bridge between these structures, mesosystem facilitates their influence. The exosystem, the third level, involves social contexts indirectly impacting on the child, though they are not directly involved, influencing their development. Lastly, the macrosystem, the outermost layer, comprises the intricate customs, values and laws significant within the child’s culture (Bronfenbrenner 1979; Gardiner and Kosmitzki 2018).

Funding

This work was supported by the Polish National Science Center [2018/29/N/HS5/00696 to J.B.K.].

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID IDs

Jan Bazyli Klakla  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1141-452

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1141-452

Paulina Szydłowska-Klakla  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2196-9940

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2196-9940

Marisol Navas  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4026-8322

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4026-8322

References

American Psychological Association (2017). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (Including 2010 and 2016 Amendments). https://www.apa.org/ethics/code (accessed 1 April 2025).

Arends-Tóth J., van de Vijver F.J.R. (2004). Multiculturalism and Acculturation: Views of Dutch and Turkish-Dutch. European Journal of Social Psychology 33(2): 249–266.

Ben-Mrad M. (2018). Polonia w Kraju Półksiężyca: Porównanie Procesu Akulturacji w Różnych Pokoleniach Migracji, in: A. Anczyk (ed.) Psychologia Kultury – Kultura Psychologii. Księga Jubileuszowa Profesor Haliny Grzymała‐Moszczyńskiej, pp. 129–138. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Sacrum.

Berry J.W. (1980). Acculturation as Varieties of Adaptation, in: A.M. Padilla (ed.) Acculturation: Theory, Models and Some New Findings, pp. 9–25. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Berry J.W. (1990). Psychology of Acculturation, in: J.J. Berman (ed.) Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1989: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, pp. 201–234. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Berry J.W. (1997). Immigration, Acculturation and Adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review 46(1): 5–34.

Berry J.W. (2023). Living Together in Culturally Diverse Societies. Canadian Psychology/ Psychologie Canadienne 64(3): 167–177.

Berry J.W., Kim U., Minde T., Mok D. (1987). Comparative Studies of Acculturative Stress. International Migration Review 21(3): 491–511.

Berry J.W., Sabatier C. (2010). Acculturation, discrimination, and adaptation among second generation immigrant youth in Montreal and Paris. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 34: 191–207.

Berry J.W., Sam, D.L. (1997). Acculturation and Adaptation. Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology 3(2): 291–326.

Birman D., Simon C.D. (2014). Acculturation Research: Challenges, Complexities, and Possibilities, in: F.T.L. Leong, L. Comas-Díaz, G.C. Nagayama Hall, V.C. McLoyd, J.E. Trimble (eds) APA Handbook of Multicultural Psychology. Theory and Research, pp. 207–230. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Boski P. (2008). Five Meanings of Integration in Acculturation Research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 32(2): 142–153.

Bourhis R.Y., Moïse L.C., Perreault S., Senécal S. (1997). Towards an Interactive Acculturation Model: A Social Psychological Approach. International Journal of Psychology 32(6): 369–386.

Bronfenbrenner U. (ed.) (1979). Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brooks J., McCluskey S., Turley E., King N. (2015). The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research. Qualitative Research in Psychology 12(2): 202–222.

Brown R., Zagefka H. (2011). The Dynamics of Acculturation: An Intergroup Perspective, in: J.M. Olson, M.P. Zanna (eds) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, pp. 129–184. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Cuadrado I., García-Ael C., Molero F., Recio P., Pérez-Garín D. (2021). Acculturation Process in Romanian Immigrants in Spain: The Role of Social Support and Perceived Discrimination. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues 40(3): 1466–1475.

Fleischmann F., Verkuyten M. (2016). Dual Identity Among Immigrants: Comparing Different Conceptualizations, Their Measurements and Implications. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 22(2): 151–165.

Gardiner H., Kosmitzki C. (2018). Lives Across Cultures: Cross-Cultural Human Development. NY: Pearson.

Gordon M.M. (1964). Assimilation in American Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Graves T.D. (1967). Psychological Acculturation in a Tri-Ethnic Community. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 23(4): 337–350.

Habermas J. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Haugen I., Kunst J.R. (2017). A Two-Way Process? A Qualitative and Quantitative Investigation of Majority Members’ Acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 60(1): 67–82.

King N. (2012). Doing Template Analysis, in: G. Symon, C. Cassel (eds) Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges, pp. 426–450. Los Angeles, Washington DC, Toronto: Sage.

Klakla J.B. (2024). Law and Acculturation. Conceptualisation and Empirical Case Study: Slavic Migrants in Poland. London: Palgrave Macmillan Cham.

Langdridge D. (2007). Phenomenological Psychology: Theory, Research and Method. Glasgow: Pearson Education.

Liebkind K., Mähönen T.A., Varjonen S., Jasinskaja-Lahti I. (2018). Acculturation and Identity, in: D.L. Sam, J.W. Berry (eds) The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology, pp. 30–49. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

López-Rodríguez L., Bottura B., Navas M., Mancini T. (2014). Acculturation Strategies and Attitudes in Immigrant and Host Adolescents. The RAEM in Different National Contexts. Psicologia Sociale 9(2): 135–157.

Maehler D.B., Daikeler J., Ramos H., Husson C., Nguyen T.A. (2021). The Cultural Identity of First-Generation Immigrant Children and Youth: Insights from a Meta-Analysis. Self and Identity 20(6): 715–740.

Mancini T., Bottura B. (2014). Acculturation Processes and Intercultural Relations in Peripheral and Central Domains among Native Italian and Migrant Adolescents. An Application of the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM). International Journal of Intercultural Relations 40: 49–63.

McAuliffe M., Triandafyllidou A. (eds) (2021). World Migration Report 2022. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Navas M., García M.C., Rojas A.J., Pumares P., Cuadrado I. (2006). Prejuicioy Actitudes de Aculturación: La Perspectiva de Autóctonos e Inmigrantes. Psicothema 18(2): 187–193.

Navas M., García M.C., Sánchez J., Rojas A.J., Pumares P., Fernández J.S. (2005). Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM): New Contributions with Regard to the Study of Acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 29(1): 21–37.

Navas M., Pumares P., Sánchez J., García M.C., Rojas A.J., Cuadrado I., Asensio M., Fernández J.S. (2004). Estrategias y Actitudes de Aculturación: la Perspectiva de Los Inmigrantes y de Los Autóctonos en Almería. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía.

Navas, M., Rojas, A.J. (2010). Aplicación del Modelo Ampliado de Aculturación Relativa (MAAR) a Nuevos Colectivos de Inmigrantes en Andalucía: Rumanos y Ecuatorianos. Sevilla: Consejería de Empleo (Junta de Andalucía).

Navas M., Rojas A. (2019). Actitudes Prejuiciosas, Proceso de Aculturación y Adaptación de Adolescentes de Origen Inmigrante y Autóctonos [Unpublished Manuscript].

Navas M., Rojas A.J., García M., Pumares P. (2007). Acculturation Strategies and Attitudes According to the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM): The Perspectives of Natives Versus Immigrants. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 31(1): 67–86.

Pałecki K. (2013). Aksjologia Prawa, in: A. Kociołek-Pęksa, M. Stępień (eds) Leksykon Socjologii Prawa, pp. 1–7. Warsaw: C.H. Beck.

Phalet K., Swyngedouw M. (2003). Measuring Immigrant Integration: The Case of Belgium. Studi Emigrazione 40(152): 773–804.

Phinney J.S. (2003). Ethic Identity and Acculturation, in: K.M. Chun, P. Balls Organista, G. Marín (eds), Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research, pp. 63–81. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Phinney J.S., Alipuria L.L. (1990). Ethnic Identity in College Students from Four Ethnic Groups. Psychological Bulletin 108(3): 499–514.

Phinney J.S., Horenczyk G., Liebkind K., Vedder P. (2001). Ethnic Identity, Immigration and Well-Being: An Interactional Perspective. Journal of Social Issues 57(3): 493–510.

Pumares P., Navas M., Sánchez J. (2007). Los Agentes Sociales Ante la Inmigración en Almería. Almería: Servicio de Publicaciones Universidad de Almería.

Redfield R., Linton R., Herskovits M.J. (1936). Memorandum on the Study of Acculturation. American Anthropologist 38: 149–152.

Rojas A.J., Navas M., Sayans-Jiménez P., Cuadrado I. (2014). Acculturation Preference Profiles of Spaniards and Romanian Immigrants: The Role of Prejudice and Public and Private Acculturation Areas. The Journal of Social Psychology 154(4): 339–351.

Rudmin F.W., Wang B., de Castro J. (2016). Acculturation Research Critiques and Alternative Research Designs, in: S.J. Schwartz, J. Unger (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Acculturation and Health, pp. 75–96. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sam D.L. (2024). 50+ Years of Psychological Acculturation Research: Progress and Challenges. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 103: 102076.

Sam D.L., Berry J.W. (2010). Acculturation: When Individuals and Groups of Different Cultural Backgrounds Meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science 5(4): 472–481.

Sam D.L., Berry J.W. (eds) (2016). The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schütze F. (2012). Analiza Biograficzna Ugruntowana Empirycznie w Autobiograficznym Wywiadzie Narracyjnym, in: K. Kaźmierska (ed.) Metoda Biograficzna w Socjologii, pp. 141–278. Kraków: Nomos.

Schwartz S. (2006). A Theory of Cultural Value Orientations: Explication and Applications. Comparative Sociology 5(2): 137–182.

Schwartz S.H. (2012). An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2(1): 1–20.

Schwartz S.J., Unger J. (eds) (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Acculturation and Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Searle W., Ward C. (1990). The Prediction of Psychological and Sociocultural Adjustment During Cross-Cultural Transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 14(4): 449–464.

Sheller M., Urry J. (2003). Mobile Transformations of Public and Private Life. Theory, Culture & Society 20(3): 107–125.

Smith J.A. (2017). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Getting at Lived Experience. The Journal of Positive Psychology 12(3): 303–304.

Tajfel H., (1984). Grupos Humanos y Categorías Sociales. Barcelona: Herder.

Tajfel H., Turner J.C. (1979). An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict, in: W.G. Austin, S. Worchel (eds) The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, pp. 33–47. Pacific Grove CA: Brooks/Cole.

Thelamour B. (2017). Applying the Relative Acculturation Extended Model to Examine Black Americans’ Perspectives on African Immigrant Acculturation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 48(9): 1457–1471.

Thelamour B., Mwangi C.A. (2021). ‘I Disagreed with a Lot of Values’: Exploring Black Immigrant Agency in Ethnic-Racial Socialization. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 85(2): 26–36.

Ward C., Kennedy A. (1993). Psychological and Sociocultural Adjustment During Cross-Cultural Transitions: A Comparison of Secondary Students Overseas and at Home. International Journal of Psychology 28(2): 129–147.

Yin R.K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. New York: Sage.

Zhang S., Verkuyten M., Weesie J. (2018). Dual Identity and Psychological Adjustment: A Study Among Immigrant-Origin Members. Journal of Research in Personality 74(3): 66–77.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.