Transforming Paths of Integration: Kosovo Albanian Migrants and Their Descendants in Germany and Switzerland

-

Author(s):Dushi, MimozaPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. , No. online first, 2025, pp. 1-22DOI: 10.54667/ceemr.2025.19Received:

28 November 2024

Accepted:29 July 2025

Published:15 September 2025

Views: 115

This paper examines the integration experiences of Kosovo Albanian migrants and their children in Germany and Switzerland, highlighting evolving perspectives across generations. Initially, many first-generation migrants considered their stay to be temporary, thus limiting engagement with integration opportunities. However, economic and political instability in Kosovo spurred family reunifications, reshaping migrants’ attitudes towards settling permanently. Drawing on 53 biographical interviews conducted between 2014 and 2016, this study reveals that first-generation migrants often faced challenges with language acquisition, employment, and social integration, which impacted on their sense of belonging. In contrast, their children, benefiting from educational opportunities and wider social networks, experienced a smoother integration process. Economic stability within families enabled this second generation to become bilingual, succeed academically and secure better employment, leading to a stronger attachment to the host society and labour markets. Despite their integration, these younger migrants retain a strong Kosovo Albanian identity and connection to their heritage, balancing personal independence with cultural belonging.

Introduction

Differences in the birthplace, age and life stage at which individuals and their children arrive in new countries are crucial factors influencing the adaptation of immigrant families to a new culture (Rumbaut 2004). These variations can significantly affect several aspects of their lives, including language and accent, educational achievements, professional qualifications, social networks and social mobility (Portes and Rumbaut 2001; Snel, Engbersen and Leerkes 2006). For instance, children who arrive at a younger age are more likely to acquire the new language quicker, speak it more fluently and adapt more seamlessly into the education system compared to older children or adults (Hakuta, Bialystok and Wiley 2003). Additionally, age and context of arrival can shape perspectives and attitudes towards both the new and the home cultures, influencing the migrants’ ethnic identity and sense of belonging (Erdal and Oeppen 2013; Portes and Rumbaut 2001).

The impact of these factors extends to the maintenance of social networks and the ability to build new ones. Younger arrivals might form friendships and integrate into peer groups more easily, while older individuals might face more significant challenges in expanding their social circles (Ryan, Sales, Tilki and Siara 2008). This, in turn, affects their social mobility and opportunities for advancement in the new country. Furthermore, these differences play a role in determining the likelihood of maintaining connections to their home country over time (Schans 2009), with some individuals fostering strong transnational ties and others gradually losing touch with their place of origin (Vertovec 2004).

To carry out comprehensive research on these dynamics, accurate records of the experiences of first- and second-generation migrants are crucial. This requires a data source that includes detailed information on the respondents’ countries of birth and, if foreign-born, their ages and dates of arrival. For native-born individuals, data on the country of birth of their mothers and fathers are equally important for understanding the intergenerational transmission of cultural traits and integration processes (Rumbaut 2004). Such detailed data allow for a nuanced analysis of the intersection of factors that shape the adaptation experiences of immigrant families in multifaceted ways.

In the case of Kosovo Albanians, migration to Western European countries began as early as the 1960s. Initially, they were low-skilled migrant workers with limited education who often sought temporary work opportunities (Iseni 2013; UNDP 2014) and were mostly men from rural areas. They lived with the hope of soon returning home, therefore they continuously sent remittances back home which were used mostly to support the wellbeing of family members and to invest in houses (Gashi 2021).

During the 1980s, an intensive process of family reunification took place, made possible by transforming temporary status into residency permits for migrant men who had been working in Western European countries for many years (Iseni 2013). Additionally, during this time, thousands registered as asylum-seekers fleeing the dire political and socio-economic situation that prevailed in Kosovo in 1989 (Iseni 2013; UNDP 2014). Skilled and educated young men from both rural and urban areas migrated to Western European countries to find jobs, escape political turmoil and poverty (UNDP 2014) and, by sending remittances, improve the quality of life for family members left behind (Gashi 2021).

This trend of migration continued and intensified during the war years of 1998–1999, when the highest emigration peak, composed of asylum-seekers and refugees, occurred (Schwander 2005; UNDP 2014). From 2000 onwards, the motivation for migration evolved as migrants sought better work opportunities and a Western standard of living (Meyer, Möllers and Buchenrieder 2012). During this period, a dichotomy emerged: well-educated young adults went abroad for education and career development, while unskilled and less-educated individuals continued to migrate (King and Gëdeshi 2024; UNDP 2014). Data from the European Training Foundation (2021) indicate an increasing trend for well-educated young adults, predominantly doctors and nurses, seeking education and career opportunities abroad.

However, it is difficult to gather accurate numbers of Kosovo Albanians residing outside the country – and their demographic and socio-economic characteristics – because the Albanian diaspora is considered new and less institutionalised (Koinova 2011), exacerbated by Kosovo’s changing status. Until Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008, Kosovo Albanians were registered in the receiving countries’ statistics, along with other national and ethnic groups of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY), as Yugoslav citizens. Later, in 2014, the Kosovo Agency of Statistics (KAS) published a report on Kosovar migration based on data collected from counterpart agencies in the respective countries. This report highlighted another challenge in measuring the number of Albanians from Kosovo accurately because detailed immigration statistics in the receiving countries struggle to differentiate between Albanians from different Western Balkan countries –namely individuals from Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia and Montenegro. The KAS still lacks comprehensive statistical data on emigration, resulting in limited information about the Kosovo diaspora: the members’ gender, age and reasons for migration (Gashi 2021). Recent studies estimate that the Kosovo Albanian diaspora numbers range from 885,862 (MIA 2021) to around 1 million, comprising a third to half of the total population born in Kosovo (King and Gëdeshi 2024; UNDP 2014). The majority, accounting for 58.1 per cent, reside in Germany and Switzerland, followed by Italy, Slovenia and Austria with 20 per cent. The United States follows with 4 per cent and the reminder mostly live in Scandinavia and Benelux (KAS 2014; MIA 2019).

While there is extensive literature on the Kosovo diaspora and remittances (Gashi 2021; Hajdari and Krasniqi 2021), research on their integration and generational dynamics remains limited. The migration patterns, directions, forms of migration and establishment of permanent residencies in European countries of the Kosovo Albanian diaspora have been the subjects of extensive study but little attention has been given to their integration strategies. This paper aims to illuminate the integration strategies used by Kosovo Albanian migrants residing in Germany and Switzerland, the migrants’ 2 primary destination countries (KAS 2014; UNDP 2014). In this study, integration strategies are understood as the actions and choices, both deliberate and situational, which migrants and their families employ to navigate social, economic and cultural inclusion in the host society. These include language learning, educational and employment decisions, as well as engagement in social networks. While some strategies are intentionally pursued, others emerge as adaptive responses to structural constraints. Drawing on established frameworks in integration research (Ager and Strang 2008), this paper analyses these key dimensions of integration not merely as outcomes but as strategic practices that reflect migrants’ agency, aspirations and constraints. By treating them as integration strategies, the study captures both the proactive and the reactive forms of migrant adaptation in Germany and Switzerland.

This study therefore examines how Kosovo Albanian migrants and their descendants in Germany and Switzerland navigate the process of integration, with a particular focus on the strategies they employ in relation to language, education, employment and social networks. Specifically, the research explores how integration strategies reflect individual agency versus passive adaptation and how they evolve across generations. Agency is understood here as the capacity of migrants to make purposeful, strategic decisions in response to structural constraints, while adaptation refers to more-reactive or situational adjustments (De Haas 2021). It introduces a comparative lens among first-generation migrants (those who migrated as adults), 1.5-generation migrants (those who were born in Kosovo but migrated with their parents before adolescence, typically before the age of 12) and second-generation migrants (those born in the host country to migrant parents) (Dolberg and Amit 2023; Rumbaut 2004). The paper investigates the hypothesis that integration strategies vary not only between generations but also within them, especially within the first generation, reflecting differences in the life stage, historical migration wave and intention to settle. By highlighting the contrast between first-generation migrants’ limited integration efforts and the more proactive engagement of 1.5- and second-generation migrants, the paper seeks to uncover the intergenerational dynamics that shape integration trajectories and identity negotiation. These domains were selected not only because they represent core dimensions of integration in the existing literature but also because they consistently emerged as central themes in the migrants’ life narratives, making them particularly well-suited for analysis through biographical interviews. A notable finding of this study is the internal variation within the first generation itself, with later arrivals, particularly those who migrated after 1989, demonstrating more proactive and long-term integration strategies than earlier Gastarbeiter cohorts. This challenges dominant assumptions in the migration literature that often treat the first generation as a homogeneous group oriented primarily toward temporary settlement and limited engagement.

Concepts of immigration and generation

Integration into host societies is a multifaceted and dynamic process that involves both structural conditions and individual agency. In this study, we use the term integration strategies to refer to the practices, decisions and adaptive responses which migrants use to navigate key areas of settlement, such as language learning, education, employment and social relationships. These strategies may be proactive (e.g., enrolling in language classes or pursuing credential recognition) or reactive (e.g., relying on co-ethnic networks due to systemic barriers). Building on Ager and Strang’s framework (2008) and integrating recent studies (Astolfo and Allsopp 2023; Giles, Västhagen, Enebrink, Ghaderi, Oppedal and Khan 2025), this study analyses how migrants engage with these domains through both agency and adaptation. While generations are often used as broad analytical categories, this study also highlights important variations within generational cohorts, particularly within the first generation, based on the timing of migration, the political context and the life stage at arrival. These differences significantly shape the strategies which migrants adopt and challenge assumptions of uniform integration patterns within generational labels. Within this framework, we apply a generational perspective to examine differences in integration strategies. People who have moved from their native regions to other countries as adults are referred to as the first generation (G1). These individuals, having spent their formative years and young adulthood in their country of origin, bring with them strong social networks and ties to their homeland (Rumbaut 2004). They can be less attached to the new country of residence and more prone to eventually returning to their country of origin compared to the second generation (G2) of migrants (Bonifazi and Paparusso 2019).

The 1.5 generation (G1.5) is a unique category encompassing individuals who were born in their country of origin but migrated with their parents before reaching the age of 12 (Dolberg and Amit 2023). According to Rumbaut (2004), these children reached elementary-school age in their native country but emigrated before reaching adolescence and lower-secondary schooling. Their emigration is thus not only a measure of their exposure to a new, often Western, life but also an indicator of the different life stages and socio-developmental contexts they experienced. G1.5 individuals develop bilingual abilities and socio-cultural hybridity. As a result, they have significant experiences in both their country of origin and their new country, although their ties to the former may be fewer and less close compared to those of G1s (Amit 2018).

In contrast, the second generation (G2) consists of individuals who were born in the country to which their parents migrated (King and Christou 2010). They have grown up in the home environments which previous generations created abroad, integrated into European social networks and typically have not resided in their parents’ country of origin. Consequently, they are likely to have fewer close ties to their ancestral homeland than G1.5 or G1 individuals, often integrating into local education and labour markets while balancing dual identities (Klok, Van Tilburg, Fokkema and Suanet 2020).

The third generation (G3) is composed of individuals who were born in the residence country to parents who were also born there (Alba, Logan, Lutz and Stults 2002). Given that G3 individuals and their parents have not lived in their ancestral country, their connection to the origin country is primary symbolic rather than based on direct experiences. As Levitt and Jaworsky (2007) note, G3 can hardly be called ‘migrants’ because their social connections with the origin country are much weaker compared to those of their parents or grandparents.

This conceptual structure enables the analysis of how integration strategies are shaped by migrants’ age at migration, life stage and generational position, providing a more dynamic and nuanced understanding of migrant adaptation process. Each generation’s specific experiences and connections to both the country of origin and the host society influence the strategies which they adopt for integration.

In particular, first-generation (G1) individuals, having migrated as adults, maintain strong social networks and many close ties to their homeland. Generation 1.5 individuals, who arrived during childhood, navigate experiences from both their country of origin and their new country but typically maintain fewer ties to their native land compared to G1s. Second-generation (G2) individuals, born in the host country, are shaped by environments created by earlier generations and are more embedded within European social networks, with even weaker links to the ancestral homeland (Klok et al. 2020). Finally, third-generation (G3) individuals, born to parents also born in the host country, are often fully integrated into the society of their birth, maintaining primarily symbolic connections to their ancestral origins (Levitt and Jaworsky 2007). Despite the extensive literature on migration patterns and remittance behaviour among the Kosovo Albanian diaspora (Gashi 2021; King and Gëdeshi 2024), there is limited research examining how their integration strategies evolve across generations, particularly through the lens of individual agency and structural negotiation. This study addresses that gap by focusing on strategic adaptation processes among first-, 1.5- and second-generation Kosovo Albanian migrants in Germany and Switzerland.

Factors affecting immigrants’ integration into host societies

Immigrant integration into host societies is shaped by interacting factors that present both challenges and opportunities for strategic engagement. According to Papademetriou et al. (2009) and recent studies (Astolfo and Allsopp 2023), 4 primary factors significantly affect integration: language proficiency, educational attainment, credential recognition and access to social networks. Each of these factors present unique challenges that can hinder immigrants’ ability to fully participate in their new society. However, migrants often respond strategically to these challenges.

Language barriers are often the most immediate and visible challenge faced by immigrants (Gales 2009; McKeary and Newbold 2010). Migrants may respond proactively by enrolling in formal language classes or, more passively, by learning the language informally at work or through social interaction. Proficiency in the host country’s language is crucial for accessing services, employment and education (Chiswick and Miller 2009). Differences in educational attainment influence integration outcomes significantly. Migrants with lower levels of education may face difficulties entering skilled labour markets, yet many engage in strategies like pursuing vocational training or attending night school to improve their qualifications (Dustman and Glitz 2011). Furthermore, even highly educated immigrants often face difficulties in gaining recognition for their foreign credentials (Bauder 2003), which can limit their employment opportunities and professional growth.

The issue of credential recognition remains a major barrier, particularly for highly educated migrants. Immigrants who were professionals in their origin countries may struggle to obtain the necessary accreditation to continue their careers in the host country (Li 2001). This can lead to underemployment and frustration (Guo 2009), as their skills and experience remain under-utilised. They often respond by either pursuing new certifications, adapting to different professions or mobilising ethnic entrepreneurial networks (Bauder 2003; Guo 2009). Social networks provide immigrants with crucial resources such as job leads, housing and community support (Hagan 1998). However, building these networks takes time and effort and immigrants may initially have limited connections in their new country. First-generation migrants initially rely heavily on co-ethnic networks; however, later generations often strategically expand these networks to include locals, colleagues and educational peers (Ryan et al. 2008).

Rather than seeing these factors purely as barriers, this study conceptualises them as fields of strategic action, where migrants negotiate, resist or adapt in context-dependent ways shaped by their generation, life stage and socio-economic background. They have differing views on whether first-generation immigrants can quickly make significant gains in wages and employment rates and whether they can catch up with their native counterparts over their lifetimes. Some analysts argue that, with time and support, immigrants can make substantial progress in the labour market (Aydemir and Skuterud 2005; Dustmann and Fabbri 2003), while others believe that the process is slower and more challenging, with persistent gaps in employment and income levels (Chiswick and Miller 2009). The situation often differs for G2s, who typically have higher levels of education and language proficiency compared to their parents (Portes and Rumbaut 2001). Growing up in the host country, second-generation immigrants tend to be better integrated into the labour market, often achieving employment rates and income levels closer to those of the native population (Algan, Dustmann, Glitz and Manning 2010). However, they may still face unique challenges related to identity and discrimination, which have possible effects on their long-term economic outcomes. Studies have shown that the second generation often plays a crucial role in bridging cultural and social gaps, leveraging their bicultural experience to navigate and succeed in both their home- and host-country environments (Aydemir and Sweetman 2007).

Education and income levels significantly influence the ease with which immigrants overcome these barriers. Individuals with higher levels of education tend to have better language skills and professional qualifications and stronger social networks, which facilitate their integration (Dustmann and van Soest 2002). They are more likely to work in their chosen professions, engage in professional development activities and become accepted into social circles of higher socio-economic status (Bourdieu 1986). Additionally, higher income levels enable immigrants to participate in cultural activities and integrate more fully into the social and cultural life of their new residence (Li 2008).

By analysing how Kosovo Albanian migrants engage proactively or reactively with language acquisition, education, employment and social networks, the paper contributes to an emerging literature on migrant agency and strategic integration (Astolfo and Allsopp 2023; Keles 2022). Understanding these patterns of agency is not only academically significant but also has practical implications for policy and community initiatives. Recognising the strategies which migrants employ highlights the crucial role that policymakers and communities can play in supporting integration processes. By creating targeted programmes for language education, credential recognition and social engagement, host societies can help to remove structural barriers and enable migrants to more fully realise their integration potential. In so doing, immigrants are better positioned to contribute meaningfully to the economic and social fabric of their new countries.

Research design and methods

Research design

This study adopts a qualitative research design, utilising biographical interviews to explore the integration strategies of Kosovo Albanian migrants across different generations in Germany and Switzerland. Biographical interviewing was chosen because it provides a rich, nuanced understanding of personal trajectories, identity negotiations and strategic responses to structural constraints, aspects that are particularly important for examining processes of migrant integration over the life course (Apitzsch and Inowlocki 2000; Rosenthal 2018).

Although the data were collected between 2014 and 2016, the findings remain highly relevant. Migration and integration processes, especially among the first and 1.5 generations, are cumulative and long-term in nature. Patterns in language acquisition, labour-market participation and identity formation observed in earlier stages continue to influence the experiences of the second generation today. Additionally, the study sheds light on the strategic adaptation practices that remain central to current debates on migrant agency and intergenerational integration.

The researcher’s positionality is also important to acknowledge. As a member of the Kosovo Albanian community, the researcher shared linguistic, cultural and social ties with many of the participants. This insider position facilitated trust and openness during the interviews but also required a critical, reflexive approach in order to minimise bias in interpreting the narratives.

Data collection

The analysis is based on 53 biographical interviews conducted with G1, G1.5 and G2 Kosovo Albanian migrants residing in Germany and Switzerland. Participants were selected through a combination of purposive and snowball sampling. Initial participants were recruited based on variation in gender, age, migration trajectory and socio-economic background and were then asked to refer others with diverse experiences.

Biographical interviewing was selected over other qualitative methods (such as focus groups or structured interviews) because it encourages participants to narrate their life histories in a relatively open, participant-driven manner. This approach is particularly suited to capturing how individuals experience and respond to integration challenges over time (Rosenthal 2018).

Interviews followed a semi-structured format. Participants were guided by a flexible interview guide which covered key themes, such as migration history, language acquisition, education, employment and social networks but which allowed space for elaboration and personal storytelling. Interviews were conducted in the Albanian language to ensure that participants could articulate their thoughts clearly and express their feeling comfortably; they ranged from 1 to 3 hours in length.

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and handled with strict attention to confidentiality. Participants gave explicit consent for their first names to be used in the study but requested that their surnames and any other sensitive information remain confidential. No pseudonyms were assigned; instead, participants’ real first names appear in the text, while any potentially identifying information they wished to keep private was excluded. The researcher ensured that all confidentiality agreements regarding sensitive information were respected throughout transcription, analysis and reporting.

Data analysis

Data analysis followed a thematic approach, combining inductive coding with sensitising concepts from migration theory (Charmaz 2014). Transcripts were imported into MAXQDA software initially in version 14 and then continued in version 24, to facilitate systematic coding and analysis. Initial codes were generated based on recurring patterns in participants’ narratives, followed by the development of broader themes related to integration strategies, generational differences and agency versus adaptation.

The coding process was iterative. Initial descriptive codes (e.g., ‘language learning efforts’, ‘credential recognition challenges’, ‘social network expansion’) were gradually refined into higher-order thematic categories (e.g., ‘proactive integration strategies’ vs ‘passive adaptations’). Throughout the analysis, attention was given to variations across generations and gender, as well as the socio-political context shaping integration opportunities.

Data limitations

While the study includes fewer participants from the 1.5 and second generations compared to the first generation, this imbalance reflects the recruitment dynamics and demographic availability at the time of fieldwork (2014–2016), when first-generation adult migrants were more accessible for in-depth biographical interviews. The original research design prioritised the life histories of labour migrants and generational distinctions were not the initial analytical focus. These distinctions became analytically productive only during the coding and interpretive phases, as participants’ narratives revealed contrasting integration strategies shaped by age at migration and life stage.

Given this inductive approach, the study does not aim for statistical generalisability. Rather, it explores thematic and strategic patterns within and across generational categories. While the number of G1.5 and G2 participants is limited, their narratives offer analytically valuable insights into evolving integration strategies and generational shifts. These findings should be viewed as exploratory and illustrative, highlighting patterns that merit further investigation with larger and more balanced samples.

Characteristics of participants

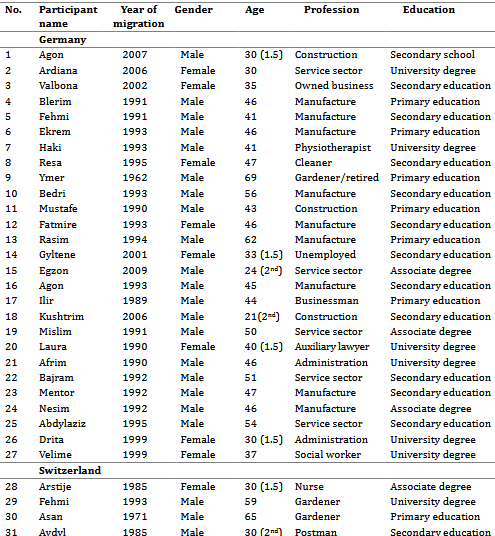

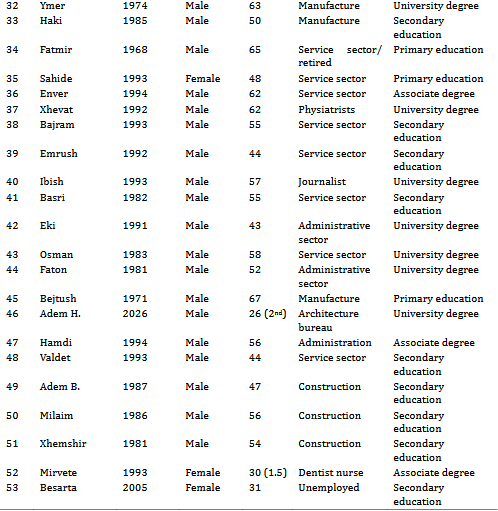

The analysis of this study relies on interviews with 53 participants: 43 interviewees were first-generation migrants, 6 were G1.5s and 4 were G2s. The migrants encompassed those with work visas, tourist visas, family reunification visas, those who entered illegally and those who sought political asylum upon reaching their destination. However, by the time of the research, all participants had regularised their status. 15.1 per cent had completed primary education, 45.3 per cent secondary education, 13.2 per cent had earned an associate’s degree and 26.4 per cent held a university diploma. In terms of employment, 35.8 per cent worked in the service and administration sectors, 22.6 per cent in manufacturing, 11.3 per cent in construction, 5.7 per cent in gardening, 3.8 per cent had their own businesses, 15.1 per cent worked in other professions and 5.7 per cent were unemployed at the time of the interview or were retired. The large majority of interviewees were men (79.2 per cent), primarily serving as initiators of labour migration across all emigration waves from Kosovo, while women (20.8 per cent) predominantly migrated for family reunification (see Table 1).

Table 1. Migrant’s profile

Results

This section explores the diverse possibilities and practices applied by Kosovo Albanian migrants in Western European countries, particularly Germany and Switzerland. It examines how integration is perceived and pursued across different generations of migrants, especially G1s, G1.5s and G2s, in relation to language, education, employment and social networks. By analysing these dimensions, the section highlights both continuous and generational shifts in integration strategies.

First generation: temporary migrants and limited integration

The data show that Kosovo Albanians initially migrated to European countries, especially Germany and Switzerland, as temporary workers under the Gastarbeiter programme (Goldon, Cameron and Balarajan 2011). Because these migrants travelled in organised groups, foreign-language proficiency was not required for entry into the labour force. Travel arrangements were facilitated, and interpreters were provided (Rass 2023). Within the workplace, teams were often organised by nationality; communication was thus feasible as long as one of the group members spoke the host country’s language or a widely understood intermediary language (Caro, Berntsen, Lillie and Wagner 2015). Asan (65, manufacturing, Switzerland) recalled his early experience: ‘We didn’t know the language, therefore there were some interpreters. At that time, the interpreters were only for Serbo-Croatian or Slovenian languages’.

In addition, no formal education was required. The programme aimed to fill labour shortages in sectors such as agriculture, construction and manufacturing, which demanded physical labour rather than academic credentials (Martiniello 2008). As a result, most migrants were men from rural areas with limited schooling. Ymer (69, retired, Germany) shared that: ‘They needed workers and we were all young and ready to work. Our labour power was important and our level of schooling didn’t matter. I only have primary-school education’.

While both language acquisition and employment are considered to be core domains of integration (Brown and Bean 2006), for many early migrants these were not pursued as pathways to long-term settlement but, rather, as means to support temporary labour migration. First-generation migrants often viewed their residence in Western Europe as short-term, hoping to return home once political or economic conditions in Kosovo improved. Fatmir (65, retired, Switzerland) reflected on this mindset:

The worst thing of my generation was that we have refused integration here, always hoping we would return soon. We believed something would happen in Kosovo and that we would go back. Therefore, we refused many possibilities regarding labour-market integration. I had a chance to work as a journalist but I refused to integrate. I couldn’t believe that would get old here.

This quote captures the regret that many first-generation migrants now express over missed opportunities. Their initial goal was to support families in Kosovo through remittances and to eventually return. However, over time, return plans were postponed indefinitely. Ymer (69, gardener, Germany) did not anticipate spending his entire life abroad. He declined a higher-paying manufacturing job, fearing it would restrict his ability to visit his family. It was not until he approached retirement that he fully acknowledged that he would remain in Germany. In his interview, he stated:

I forgot to mention that, once, I had the chance to switch from gardening to a job in a Mercedes car factory. However, I refused, even though the salary was much higher and there were many other benefits. The problem was that they offered vacations only once a year and I needed to visit my family in Kosovo more often.

The temporary structure of the Gastarbeiter programme was designed to address labour shortages by recruiting workers from countries like Turkey, Yugoslavia and Kosovo (Schmid 1983). These programmes did not prioritise integration, nor require language skills or educational qualifications. However, this structure inadvertently hindered deeper social and economic inclusion. The temporary mindset among first-generation migrants often resulted in minimal investment in language learning, education and career advancement. Over time, many expressed regret at not having made fuller use of the opportunities available to them, highlighting the long-term costs of an initial orientation toward short-term goals. These findings show that the logic of temporary migration significantly limited first-generation migrants’ strategic engagement with integration opportunities. Rather than investing in long-term settlement, such as language acquisition, formal education or upward mobility, many pursued survival-oriented strategies focused on remittances and eventual return. This short-term orientation shaped their low engagement with host-country institutions and contributed to patterns of partial or delayed integration. Such experiences echo earlier research that has described Gastarbeiter trajectories as structurally constrained and shaped by circular-migration expectations (Schmid 1983).

Language barriers and co-ethnic social networks

Due to the limited need for language skills at the time of their migration, deeper integration into the host society was delayed for many first-generation Kosovo Albanian migrants. As temporary workers, they often lacked access to structured integration programmes that could have supported their acquisition of the host country’s language and culture. Consequently, many who continue to reside in Germany or Switzerland today still report only basic language proficiency. Ymer (69, retired, Germany) explained: ‘To be honest, I never learned German well. Even now, I am unable to speak fluently. I understand everything but my speaking and reading skills are not satisfactory. I make mistakes’.

This limited language ability significantly reduced opportunities to communicate with locals and form meaningful relationships. Initially – and often exclusively – first-generation migrants developed connections through work colleagues. Friendships with locals were rare and generally remained superficial. Bejtush (67, manufacturing, Switzerland) reflected: ‘I still greet them when we meet on the street but I could never really become close friends’.

As a result, social networks were primarily developed with co-ethnics within workplaces and residential areas, reinforcing a strong orientation towards the home country (Caro et al. 2015). These migrants relied heavily on their ethnic community for emotional support, practical advice and mutual assistance. They shared experiences, maintained cultural traditions and helped each other to navigate unfamiliar systems. Within these networks, many found a sense of familiarity and cultural continuity in an otherwise foreign context. Ymer (63, manufacturing, Switzerland) noted how these networks grew and became further embedded over time: ‘I spend the weekends with Albanians. We are many relatives here. Also, over time our circle has increased through the marriages of our children’.

These findings suggest that co-ethnic networks were not merely fallback options but strategic responses to exclusion and marginality. They provided psychological security and community continuity in the absence of structural support for integration. At the same time, heavy reliance on co-ethnic ties limited broader social integration and reinforced patterns of social segmentation. Without host-language fluency or engagement with formal institutions, many first-generation migrants remained at the periphery of host societies.

This section highlights the fact that early first-generation migrants were shaped by a circular migration logic that discouraged investment in long-term integration. Their decisions were pragmatic and survival-oriented, focused on remittances and short-term employment. Their adaptation strategies, such as reliance on co-ethnic networks, were reactive rather than proactive, reflecting both institutional neglect and the migrants’ own expectations of return. The experiences described here align with the literature on structurally constrained migration (Schmid 1983) and demonstrate how short-term intentions can become long-term exclusion. This stands in contrast to later waves of migrants, whose strategies would evolve toward long-term settlement, as the next section of the paper explores.

Transition to later migrants: The integration of Kosovo Albanian migrants post-1989 – a shift in strategies

Language acquisition efforts and employment adaptation

While the earlier wave of G1 Kosovo Albanain migrants often adopted passive, survival-focused approaches to integration, the cohort who migrated in the late 1980s and early 1990s demonstrated a markedly different pattern. Although still classified as first generation, these later migrants employed more proactive strategies, particularly in language learning, continued education and employment adaptation, indicating a broader shift from temporary survival toward long-term settlement.

Following the abolition of Kosovo’s autonomy in 1989, Kosovo Albanian workers were systematically dismissed from public service and socially owned enterprises (UNDP 2014). These political and economic upheavals reshaped the migrant profile. Skilled and educated young men, from both rural and urban backgrounds, migrated to Western European countries to escape conscription into the Yugoslav army and to secure employment (Iseni 2013; King and Gëdeshi 2024; UNDP 2014).

Unlike earlier temporary labour migrants, these individuals approached migration with long-term goals. They actively pursued host-country language learning as a gateway to social and economic integration, recognising it as an investment in future integration. As Afrim (46, post-office consultant, Germany) recalled:

I enrolled in the Goethe Institute in Munich, which was very expensive at the time but was known for its high standards in teaching the German language. I studied there for about 9 months and learned literary German, not just the colloquial language one picks up on the street.

Despite their credentials, many faced significant challenges upon arrival. Their qualifications were often not recognised, leading to underemployment and professional frustration. However, rather than remaining stagnant, many responded by pursuing retraining or additional education to improve their employment status and better integrate into the host society. Xhevat (62, psychiatrist, Switzerland), formerly a doctor and university lecturer in Kosovo, described his adaptation process:

I pursued further education in psychology, specialising in psychological trauma and psychotherapy for couples and families. My workplace funded this training, which lasted three and a half years.

Others, confronted with systematic barriers to credential recognition, took alternative routes to economic stability. Enver (62, service sector, Switzerland) reflected: ‘I had my degree in physics and worked as a teacher at a secondary school but they did not recognise it. I had to start all over. Now I am working in a post office’.

These narratives reflect how post-1989 migrants responded strategically to structural constraints. Rather than accepting marginalisation, they invested in host-country credentials, retraining or shifting career paths entirely. This marks a departure from the circular migration logic in earlier cohorts and demonstrates a turn towards long-term settlement and deeper institutional engagement.

Although these migrants maintained strong co-ethnic ties, their reliance on social networks was not limited to emotional support. These networks served as vital practical resources, facilitating access to housing and employment opportunities and to navigating bureaucratic systems. While the shared cultural background provided familiarity and security, these networks also became functional tools for managing daily life in a new country.

Initially, many in this cohort still viewed their stay as temporary. However, over time, driven by changing life circumstances, economic opportunity and political instability in Kosovo, a gradual transition towards permanent settlement occurred. This adaptive strategy reflects a broader shift in integration logic. Earlier migrants followed short-term, return-oriented strategies; later first-generation migrants embraced more goal-oriented, agency-driven approaches. Through investment in language, education and credential recognition, they sought upward mobility and belonging in the host society. These patterns reinforce the paper’s theoretical claim: that integration is not merely shaped by state policy or institutional access but also by migrants’ ability to act strategically within, and despite, constraints.

Family reunification, shifting aspirations and investment in children’s education

Following the events of 1989, many Kosovo Albanian families initiated family reunification processes, joining relatives already settled in Western Europe. In contrast to earlier migrants, who generally considered their stay to be temporary, post-1989 migrants increasingly envisioned permanent futures in the host country. Political instability at home, labour demand abroad and changes in immigration policy facilitated legal regularisation and reunification (Castles 2006; Iseni 2013). This shift represented not just a legal adjustment but also a transformation in migration logic, from short-term survival to long-term, future-oriented planning. Fehmi (59, gardener, Switzerland) captured this shift clearly: ‘We realised that Kosovo would not be the same again. It was clear that we had to build our life here’.

As families reunited and settled, their integration efforts centred increasingly on supporting their children’s adaptation. Parents viewed their children not simply as dependents but as central to the family’s collective success in the host society. Many enrolled them early in school, prioritised host-country language acquisition and encouraged friendships with local peers as part of a deliberate effort to secure their children’s future. Astrije (30, nurse, Switzerland), a 1.5-generation migrant, recalled:

Dad worked hard with us. He pushed us to learn the language by buying different dictionaries, sending us to buy something on our own to learn orientation and inviting Swiss neighbours’ children to play in our garden to make friends.

These efforts reflect a form of collective agency, where families engaged in strategic, multigenerational integration planning. Parents understood that success in the host country depended on their children’s ability to thrive socially and educationally, an understanding that informed their everyday actions and priorities. Children who arrived at a young age typically adapted quickly, especially through school systems. Drita (30, lawyer assistant, Germany) shared: ‘They immediately sent us to kindergarten. I learned German with my peers’.

Importantly, integration did not come at the cost of cultural identity. Many families simultaneously invested in cultural and linguistic preservation. Supported by Kosovo’s diaspora strategy (Gashi 2021), Albanian language schools became important institutions for maintaining national identity. These schools taught not only the language but also history, geography and cultural practices. Egzon (24, city bus driver, Germany), who migrated as a child, explained:

My father sent us to the Albanian language school twice a week. There, we didn’t just learn the language but also geography, history, culture, traditional Albanian dance, and many other things. Today, I feel proud when I visit Kosovo and understand everything there. I speak Albanian perfectly.

These practices show how integration and cultural retention were not opposing forces but, rather, dual goals pursued simultaneously through conscious planning. Parents actively positioned their children to succeed within the host society while maintaining a strong sense of ethnic identity, thus reshaping traditional models of integration that assume a trade-off between adaptation and cultural continuity.

For many parents, especially those employed in low-skilled or precarious jobs, education became the principal channel for securing long-term integration. They often expressed a deep sense of purpose and pride in seeing their children access opportunities which they themselves could not. Sahide (48, sales clerk, Switzerland) emphasised this generational strategy: ‘I may work a simple job but my children are studying. That’s our future’.

This framing of education as a long-term integration investment is key. It reveals how migrant families acted as collective agents, adapting not just in response to immediate challenges but also with an eye towards future stability and mobility. Education served as the site where long-term aspirations could be realised, even if parents had to sacrifice their own career ambitions. Fatmir (65, retired, Switzerland) reflected on his children’s achievements: ‘Children are integrated. My older son is a manager in an organisation and the younger one is an artist. He has his own art gallery’.

Likewise, Xhevat (62, psychiatrist, Switzerland) noted: ‘My son, who came here at 6 years old, benefited the most. Now he is 24 and studying biochemistry at one of the most challenging faculties here, which is considered even harder than medicine’.

These narratives reveal that migrant integration is rarely an individual or linear process. Rather, it is a dynamic, intergenerationally negotiated pathway in which families make intentional investments – educational, social and cultural – to secure a sense of belonging and stability over time. These lived experiences challenge narrow, institutional definitions of integration and support the paper’s theoretical argument: that integration must be understood as a dynamic, generational process shaped not just by structural conditions but also by long-term aspirations negotiated across generations.

Perspectives of 1.5 and second-generation migrants: Evolving integration strategies

Language fluency and cultural hybridisation

The integration experiences of 1.5 and second-generation Kosovo Albanian migrants illustrate how early exposure to the host society fosters new forms of belonging, mobility and identity formation. While both groups benefit from educational access and linguistic fluency, their trajectories reflect distinct patterns shaped by age at migration, structural inclusion and evolving perceptions of self. Both groups demonstrated high levels of fluency in the host-country language, though the pathways differed. Mirvete (30, dental nurse, Switzerland, G1.5) recalled: ‘I had to learn German very quickly because I was thrown into school without much help’.

For G1.5 migrants, language acquisition was often an urgent, high-stakes process shaped by sudden immersion in unfamiliar school environments without preparatory support. In contrast, second-generation migrants typically acquired the host-country language from early childhood, through home, schooling and peer interaction, resulting in more-fluid, intuitive bilingualism. Egzon (24, service sector, Germany, G2) noted: ‘German is my first language. I only speak Albanian at home with my parents and siblings’.

These differing experiences signal a generational shift: G1.5 migrants actively negotiated bilingualism and cultural boundaries, balancing dual identities through effort and adaptation. Second-generation youth, by contrast, experienced bilingualism as normalised and cultural hybridity as seamlessly integrated into their lives. For them, navigating between their Albanian heritage and their host-society belonging felt less stressfull and more like a natural feature of daily life.

Yet, even when linguistic and institutional integration was strong, emotional and cultural identity often remained complex. Laura (40, legal custodian, Germany, G1.5) shared her experience of applying for German citizenship:

When I applied for a German passport, I had to convince them that I was integrated. It was hard for me, born as an Albanian. I emphasised that I am Albanian and belong to the Schwaben neighbourhood where I was born. I told them that, no matter what, I belong to Germany but never feel German.

Such narratives underscore the nuanced and sometimes conflicted nature of identity for 1.5-generation migrants, deeply embedded in the host society, yet not always fully embraced by it. They often feel socially and professionally integrated but cultural acceptance and emotional belonging remain conditional and context-specific. Astrije (30, nurse, Switzerland, G1.5) similarly reflected:

I have spent my whole life here, so I can’t feel only Albanian. When Swiss people ask about nationality, they ask which language you think in. I still think in Albanian. Therefore, they always tell me I am Albanian, not yet Swiss. Also, when we apply for a passport, they ask which language do you think and dream in. For me, it’s still Albanian.

These reflections reveal that integration is not simply a matter of formal participation or linguistic fluency but also involves a deeply personal negotiation of identity. Even among second-generation migrants, emotional and cultural ties to Kosovo remain strong. Drita (30, lawyer assistant, Germany, G2) summed it up: ‘We still go to Kosovo for vacations. However, here in Germany, we have our schools, jobs, friends and family. Home is where the family is’.

These narratives suggest that identity among 1.5 and second-generation Kosovo Albanian migrants is best understood as relational, negotiated and hybrid. While structural inclusion facilitates external integration, internal belonging remains shaped by memory, affective ties and how migrants are perceived and accepted by the host society. These findings support theoretical models that conceptualise integration as a strategic, generational and multidimensional process, where agency is exercised not only in navigating institutions but also in constructing and maintaining dual identities. Rather than signaling incomplete integration, this hybridity reveals adaptive resilience and flexible identity work that allows migrants to belong in multiple cultural worlds simultaneously.

Educational trajectories and employment aspirations

Education emerged as a central pillar of strategic integration for both 1.5 and second-generation Kosovo Albanian migrants. However, their educational experiences were shaped by differing entry points into the host society, varying degrees of familiarity with institutional systems and diverse forms of familial and social support. G1.5 migrants often described their initial difficulties in adjusting to unfamiliar educational systems, dealing with language barriers and adapting to new classroom expectations. Despite these challenges, many emphasised how parental encouragement and personal determination motivated their persistence. Agon (30, construction, Germany, G1.5) recalled: ‘I remember feeling so lost at first. But my parents insisted: “This is your chance”’.

For many G1.5 migrants, education was seen as an opportunity to regain or even exceed the professional and social standing lost due to displacement. Academic achievement became a form of strategic adaptation, to enable migrants not only to integrate into host societies but also to reposition themselves socio-economically. Second-generation migrants, by contrast, experienced smoother transitions into the educational system. Having been raised within the host-country school system, they viewed academic progress as a normative expectation. Adem (26, architecture bureau, Switzerland, G2) explained: ‘Everyone in my class aimed for university. It was normal’.

These intergenerational dynamics shaped not only how migrants approached schooling but also how they envisioned their professional lives. For both generations, education was not just a requirement but a strategic foundation for social mobility, allowing them to pursue careers in different fields. This proactive engagement reflects a long-term orientation toward integration, moving beyond survival and towards contribution and recognition within the host society.

This section has illustrated how education and employment aspirations intersect as core pillars of strategic integration. G1.5 migrants relied on adaptive resilience and family support to navigate unfamiliar terrain, while second-generation youth benefited from earlier access and normalised expectations. In both cases, education was leveraged not simply as an individual asset but as a generational investment, a bridge toward full societal participation and long-term stability.

These findings reinforce the theoretical framing of integration as shaped by agency, aspiration and structural navigation, rather than passive assimilation. Both generations approached education as a conscious strategy to overcome structural constraints, reposition themselves within the host society and fulfill family-based integration goals.

Conclusion

This paper advances our understanding of the various strategies used by Kosovo Albanian migrants and their descendants in Germany and Switzerland to navigate integration across generations and migration waves. This study was motivated by the limited scholarly attention paid to the integration strategies, rather than remittance behaviour, of the Kosovo Albanian diaspora, especially as they evolve across generations. Drawing on 53 biographical interviews, it investigates how migrants engage with core integration domains, language, education, employment and social networks, not merely as passive participants shaped by policy environments but as strategic actors who adapt, resist and negotiate their inclusion within host societies. The study treats integration as a generationally differentiated and multidimensional process, framed within Ager and Strang’s (2008) conceptual model of integration and grounded in theories of individual agency and life-course migration (Portes and Rumbaut 2001; Rumbaut 2004).

By applying a comparative lens across generational positions, early first-generation migrants, post-1989 later first-generation migrants and the 1.5 and second generations, this study fills a key gap in the literature. Existing research has largely centred on the Kosovo Albanian diaspora’s roles in remittance economies and migration patterns, while overlooking their integration strategies within host societies. This paper extends that conversation by analysing how these strategies differ not only across generations but also within generational cohorts, based on historical and socio-political contexts.

The findings reveal that early first-generation migrants, particularly those recruited through the Gastarbeiter programme, often engaged in passive or survival-based strategies. Integration was limited by their perception of temporary stay, minimal language acquisition and reliance on co-ethnic social networks. While not necessarily a rejection of integration, these migrants’ choices were shaped by limited structural support and expectations of return, resulting in under-utilised opportunities for long-term mobility. Their experiences align with classical models of circular migration and demonstrate how temporary migration frameworks shape long-term marginality.

In contrast, later first-generation migrants who arrived after 1989 exhibited notably different, more proactive strategies. In response to systemic displacement and political repression, these migrants pursued host-country language learning, professional retraining and family reunification, with a clear orientation toward settlement and stability. Their actions reveal strategic engagement with integration infrastructures and mark a shift from short-term survival to long-term inclusion. A notable and somewhat unexpected contribution of this study is the identification of variation not only across generations but also within generational cohorts, particularly within the first generation itself. Later arrivals, although technically part of the same generational category, demonstrated distinctly different integration logics than earlier Gastarbeiter cohorts. This finding challenges dominant assumptions in the migration literature that treat the first generation as a homogeneous group oriented primarily toward temporary settlement and limited engagement. Recognising such intra-generational distinctions is vital for developing a more nuanced, historically sensitive understanding of integration.

Among 1.5 and second-generation migrants, the process of integration was often facilitated by early or native-born exposure to host-country institutions, particularly the education system. While G1.5 migrants spoke of initial struggles and the need to rapidly adapt, they emphasised educational perseverance and resilience. Second-generation migrants, on the other hand, experienced smoother transitions, viewing educational success and professional ambitions as normalised expectations. Across both groups, language fluency and bicultural identity emerged as defining features. These migrants described navigating dual affiliations with confidence, yet also expressed ambivalence about full belonging, a reminder that emotional and symbolic integration may not always align with institutional inclusion.

What ties these generational experiences together is the presence of both proactive and reactive strategies. Migrants did not uniformly accept structural barriers; rather, they navigated them with varying degrees of foresight, agency and adaptation. Proactive strategies, such as investing in education, acquiring host-country credentials or fostering bilingualism, were particularly evident among later first- and second-generation migrants. In contrast, more-reactive strategies, like relying on co-ethnic networks or informal language learning, dominated earlier migration waves. Yet even these reactive adaptations reflected pragmatic responses to constrained opportunity structures.

By highlighting these strategic distinctions, the paper reinforces its theoretical contribution: integration is best understood not as a static condition or uniform path but as a context-dependent, generationally negotiated and strategic process. Migrants are not merely shaped by the societies into which they enter; they also shape their own futures through deliberate decisions made across life stages and within families.

This study thus offers a more dynamic and differentiated perspective on integration, with practical implications for both research and policy. It underscores the need for host-country institutions to recognise the diversity of migrant strategies and the long-term, intergenerational investments which many families make in securing inclusion. Future research would benefit from a further disaggregating of first-generation experiences and from examining how socio-political turning points, such as post-1989 migration, reshape migrant expectations and behaviour.

In conclusion, the integration of Kosovo Albanian migrants in Western Europe cannot be captured through singular models or outcomes. Rather, it reflects a spectrum of lived experiences, each informed by history, structure and personal strategy. Attending to these differences deepens our understanding of integration as a negotiated process that unfolds not only across borders but across generations.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to extend sincere thanks to all the study participants for their time and valuable insights. I would also like to express my gratitude to my colleagues from the ICM-RRPP research project, Erka Caro and Armela Xhaho, for their invaluable support in conducting this research.

Funding

This paper is supported by Regional Research Promotion Programme (RRPP) through ICM-RRPP research project (nr. AL-225). The RRPP is coordinated and operated by the Interfaculty Institute for Central and Eastern Europe (IICEE) at the University of Fribourg (Switzerland). The programme is fully funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), Federal Department of Foreign Affairs.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID ID

Mimoza Dushi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1853-6829

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1853-6829

Data availability statement

The qualitative data obtained from this research is not accessible to third parties.

References

Ager A., Strang A. (2008). Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Refugee Studies 21(2): 166–191.

Alba R., Logan J., Lutz A., Stults B. (2002). Only English by the Third Generation? Loss and Preservation of the Mother Tongue among the Grandchildren of Contemporary Immigrants. Demography 39(3): 467–484.

Algan Y., Dustmann C., Glitz A., Manning A. (2010). The Economic Situation of First- and Second‐Generation Immigrants in France, Germany and the United Kingdom. The Economic Journal 120(542): F4–F30.

Amit K. (2018). Identity, Belonging and Intentions to Leave of First- and 1.5-Generation FSU Immigrants in Israel. Social Indicators Research 139(3): 1219–1235.

Apitzsch U., Inowlocki L. (2000). Biographical Analysis: A ‘German’ School? In: P. Chamberlayne, J. Bonart, T. Wengraf (eds) The Turn to Biographical Methods in Social Science, pp. 53–70. London: Routledge.

Astolfo G., Allsopp H. (2023). The Coloniality of Migration and Integration: Continuing the Discussion. Comparative Migration Studies 11, 19.

Aydemir A., Skuterud M. (2005). Explaining the Deteriorating Entry Earnings of Canada’s Immigrant Cohorts, 1966–2000. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique 38(2): 641–672.

Aydemir A., Sweetman A. (2007). First- and Second-Generation Immigrant Educational Attainment and Labor Market Outcomes: A Comparison of the United States and Canada. Research in Labor Economics 27: 215–252.

Bauder H. (2003). Brain Abuse, or the Devaluation of Immigrant Labour in Canada. Antipode 35(4): 699–717.

Bonifazi C., Paparusso A. (2019). Remain or Return Home: The Migration Intentions of First‐Generation Migrants in Italy. Population, Space and Place 25(2): e2174.

Bourdieu P. (1986). The Forms of Capital, in: J.G. Richardson (ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, pp. 241–258. New York: Greenwood Press.

Brown S.K., Bean F.D. (2006). Assimilation Models, Old and New: Explaining a Long-Term Process. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/assimilation-models-old-and-new-... (accessed 29 July 2025).

Caro E., Berntsen L., Lillie N., Wagner I. (2015). Posted Migration and Segregation in the European Construction Sector. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41(10): 1600–1620.

Castles S. (2006). Guestworkers in Europe: A Resurrection? International Migration Review 40(4): 741–766.

Charmaz K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory. London: Sage.

Chiswick B.R., Miller P.W. (2009). The International Transferability of Immigrants’ Human Capital Skills. Economics of Education Review 28(2): 162–169.

De Haas H. (2021). A Theory of Migration: The Aspirations–Capabilities Framework. Comparative Migration Studies 9, 8.

Dolberg P., Amit K. (2023). On a Fast-Track to Adulthood: Social Integration and Identity Formation Experiences of Young Adults of 1.5-Generation Immigrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49(1): 252–271.

Dustmann C., Fabbri F. (2003). Language Proficiency and Labour Market Performance of Immigrants in the UK. The Economic Journal 113(489): 695–717.

Dustmann C., Glitz A. (2011). Migration and Education, in: E. Hanushek, S. Machin, L. Woessmann (eds) Handbook of the Economics of Education, pp. 327–439. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Dustmann C., van Soest A. (2002). Language and the Earnings of Immigrants. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55(3): 473–492.

Erdal M.B., Oeppen C. (2013). Migrant Balancing Acts: Understanding the Interactions between Integration and Transnationalism. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39(6): 867–884.

European Training Foundation (2021). Kosovo: Education, Training and Employment Developments. Turin: ETF.

Gales T. (2009). The Language Barrier between Immigration and Citizenship in the United States, in: G. Extra, M. Spotti, P. Van Avermaet (eds) Language Testing, Migration and Citizenship: Cross-National Perspectives on Integration Regimes, pp. 191–210. New York: Continuum.

Gashi A. (2021). How Migration, Human Capital and the Labour Market Interact in Kosovo. https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-07/migration_kosovo.pdf (accessed 29 July 2025).

Giles C.J., Västhagen M., Enebrink P., Ghaderi A., Oppedal B., Khan S. (2025). ‘Aiming for Integration’ – Acculturation Strategies among Refugee Youth in Sweden: A Qualitative Study Using a Resilience Framework. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 35: e70066.

Goldon I., Cameron G., Balarajan M. (2011). Exceptional People. How Migration Shaped Our World and Will Define Our Future. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Guo S. (2009). Difference, Deficiency, and Devaluation: Tracing the Roots of Non-Recognition of Foreign Credentials for Immigrant Professionals in Canada. Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education 22(1): 37–52.

Hagan J.M. (1998). Social Networks, Gender, and Immigrant Incorporation: Resources and Constraints. American Sociological Review 63(1): 55–67.

Hajdari L., Krasniqi J. (2021). The Economic Dimension of Migration: Kosovo from 2015 to 2020. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8(1): 1–8.

Hakuta K., Bialystok E., Wiley E. (2003). Critical Evidence: A Test of the Critical-Period Hypothesis for Second-Language Acquisition. Psychological Science 14(1): 31–38.

Iseni B. (2013). Albanian-Speaking Transnational Populations in Switzerland: Continuities and Shifts. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 13(2): 227–243.

KAS, Kosovo Agency of Statistics (2014). Kosovan Migration. Prishtina: Kosovo Agency of Statistics, Prishtina. https://ask.rks-gov.net/media/1380/kosovan-migration-2014.pdf (accessed 22 March 2023).

Keles J.Y. (2022). Return Mobilities of Highly Skilled Young People to a Post-Conflict Region: The Case of Kurdish-British to Kurdistan–Iraq. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48(3): 790–810.

King R., Christou A. (2010). Diaspora, Migration and Transnationalism: Insights from the Study of Second-Generation ‘Returnees’, in: R. Bauböck, T. Faist (eds) Diaspora and Transnationalism: Concepts, Theories and Methods, pp. 167–183. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

King R., Gëdeshi I. (2024). The Albanian Scientific Diaspora from Kosovo: Prospects for Cooperation and Return. Brighton: University of Sussex, Sussex Centre for Migration Research.

Klok J., Van Tilburg T., Fokkema T., Suanet B. (2020). Comparing Generations of Migrants’ Transnational Behaviour: The Role of the Transnational Convoy and Integration. Comparative Migration Studies 8, 46.

Koinova M. (2011). Diasporas and Secessionist Conflicts: The Mobilization of the Armenian, Albanian and Chechen Diasporas. Ethnic and Racial Studies 34(2): 333–356.

Levitt P., Jaworsky B.N. (2007). Transnational Migration Studies: Past Developments and Future Trends. Annual Review of Sociology 33: 129–156.

Li P.S. (2001). The Market Worth of Immigrants’ Educational Credentials. Canadian Public Policy/Analyse de Politiques 27(1): 23–38.

Li P.S. (2008). The Role of Foreign Credentials and Ethnic Ties in Immigrants’ Economic Performance. Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers canadiens de sociologie 33(2): 291–310.

Martiniello M. (2008). The New Migratory Europe: Towards a Proactive Immigration Policy? In: C.A. Pearsons, T.M. Smeeding (eds) Immigration and the Transformation of Europe, pp. 298–326. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McKeary M., Newbold B. (2010). Barriers to Care: The Challenges for Canadian Refugees and Their Health Care Providers. Journal of Refugee Studies 23(4): 523–545.

Meyer W., Möllers J., Buchenrieder G. (2012). Who Remits More? Who Remits Less? Evidence from Kosovar Migrants in Germany and Their Households of Origin. Oxford Development Studies 40(4): 443–466.

MIA, Ministry of Internal Affairs (2019). Profili i lehtë i migrimit 2018. https://mpb.rks-gov.net/Uploads/Documents/Pdf/AL/36/PROFILI%20I%20LEHTE%... (accessed 30 July 2025)

MIA, Ministry of Internal Affairs (2021). Profili i lehtë i migrimit 2020. https://mpb.rks-gov.net/Uploads/Documents/Pdf/AL/371/Profili per cent20i per cent20Lehte per cent20i per cent20Migrimit per cent202020.pdf (accessed 30 July 2025)

Papademetriou D.G., Somerville W., Sumption M. (2009). The Social Mobility of Immigrants and Their Children. Washington: Migration Policy Institute.

Portes A., Rumbaut R.G. (2001). Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Rass C. (2023). ‘Gastarbeiter’ – ‘Guest Worker’. Translating a Keyword in Migration Politics. Osnabrück: Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies (IMIS), University of Osnabrück, IMIS Working Paper 17.

Rosenthal G. (2018). Interpretive Social Research: An Introduction. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen.

Rumbaut R.G. (2004). Ages, Life Stages, and Generational Cohorts: Decomposing the Immigrant First and Second Generations in the United States. International Migration Review 38(3): 1160–1205.

Ryan L., Sales R., Tilki M., Siara B. (2008). Social Networks, Social Support and Social Capital: The Experiences of Recent Polish Migrants in London. Sociology 42(4): 672–690.

Schans D. (2009). Transnational Family Ties of Immigrants in the Netherlands. Ethnic and Racial Studies 32(7): 1164–1182.

Schmid C. (1983). Gastarbeiter in West Germany and Switzerland: An Assessment of Host Society–Immigrant Relations. Population Research and Policy Review 2: 233–252.

Schwander S.S. (2005). Albanian Migration and Diasporas: Old and New Perspectives, in: IOM (ed.) Workshop on the Strategy for Migration, pp. 105–122. https://albania.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1401/files/documents/44.%252... (accessed 29 July 2025).

Snel E., Engbersen G., Leerkes A. (2006). Transnational Involvement and Social Integration. Global Networks 6(3): 285–308.

UNDP (2014). Kosovo Human Development Report 2014. Migration as Force for Development. Kosovo: UNDP. https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/khdr2014english.pdf (accessed 30 October 2024).

Vertovec S. (2004). Migrant Transnationalism and Modes of Transformation. International Migration Review 38(3): 970–1001.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.