Why Exit? Exploring the Motivations of Displaced Ukrainians Leaving Norway

-

Author(s):Aasland, AadneDeineko, OleksandraPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. , No. online first, 2025, pp. 1-20DOI: 10.54667/ceemr.2025.11Received:

1 October 2024

Accepted:24 June 2025

Published:16 July 2025

Views: 5467

What prompts people to leave a welfare state and return to a home country in war? This paper examines why Ukrainians who fled to Norway due to the war voluntarily returned home or moved elsewhere. Using an exploratory research design, the study investigates how characteristics of Norwegian society, emotional ties and networks influence these decisions. The article applies a framework of individual, structural and policy-related factors to show how conditions in both the home and the host country interact. Theories on transnationalism and belonging highlight how returnees and onward movers maintain their connections to Norway. The findings reveal that social obligations, such as caring for relatives and children’s well-being, often outweigh security concerns. Among structural factors, a ‘paradox of leaving’ emerges, where aspects of the welfare state, such as Norway’s healthcare system, can motivate departure due to cultural differences in medical treatment. Limited job opportunities also drive exit, compounded by public discourse reinforcing ‘limiting beliefs’ about employment prospects. Finally, the study highlights how many displaced Ukrainians adopt a transnational approach, maintaining multiple attachments that include Norway.

Introduction

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, many Ukrainian citizens sought protection in other European countries. Unlike economic migrants, most Ukrainians did not plan to migrate but were forced to flee due to the war. This has implications for both their integration and their return aspirations. At the start of 2025, Norway had granted collective protection – the status given to protection-seekers after the full-scale invasion – to more than 88,000 Ukrainians.1 This is substantially more than the other Scandinavian countries.

According to IOM (2025), over 1 million Ukrainians have returned from abroad since the full-scale invasion. Although most of them have returned from neighbouring countries, many have also returned from states with a high level of welfare, such as Germany. At the time of writing (January 2025), of those registered for collective protection in Norway, about 79,000 still had valid collective protection, suggesting that the remainder (just over 9,000 people) were likely to have left the country.2 This article seeks to explore these people’s motivation for leaving Norway after a relatively short time. Norway ranks high on international indices of welfare and happiness (Helliwell, Layard, Sachs, De Neve, Aknin and Wang 2024; UNDP 2024) and, according to most migration theories, Norway is a country which people are more likely to move to rather than from, due in part to its low unemployment rate, high incomes, stable political situation and generous welfare state. Norway also stands out favourably in terms of the support provided to displaced Ukrainians compared to many other countries (Hernes, Danielson, Tvedt et al. 2023a). Unlike other groups of migrants, displaced Ukrainians are returning to an ongoing active war. Additionally, they are in the initial phase of their stay in Norway, receiving generous support from the state and various integration opportunities. The issue as such is what causes people who have embarked on the longer journey to Norway, rather than to a neighbouring country, to make the seemingly unlikely decision to leave after a relatively short stay.

This study contributes to the migration scholarship by exploring the motivations of such ‘unlikely leavers’, potentially revealing aspects of European host societies that may be less apparent among those who remain over time. By examining the experiences of early leavers, this study sheds light on potential mismatches between expectations and realities in host societies, offering insights into factors that shape refugee mobility beyond traditional push and pull dynamics.

The article addresses two main research questions:

- What factors contributed to the decision to leave Norway? To what extent were characteristics of Norwegian society a major reason for leaving?

- Have displaced Ukrainians who have left Norway developed emotional or network ties to the country that they also retained after returning or moving onwards?

Conceptual framework

Reasons for refugee return and onward migration

While different groups of migrants may share similar aspirations to migrate or return (Carling, Bolognani, Erdal, Ezzati, Oeppen, Paasche, Pettersen and Sagmo 2015; de Haas 2011), refugees are likely to have distinct rationales for their decisions to return or move onwards to other counties (Hernes, Aasland, Deineko and Handå Myhre 2025). Koser and Kuschminder (2015) separate the determinants of refugees’ return migration into 3 broad categories: structural (conditions in both the host and the home country), individual (including individual attributes such as age and gender and social relations such as family and networks) and policy interventions.

In an analysis of over 150 countries from 1991–2018, Zakirova and Buzurukov (2021) found that the strongest predictors of refugee return migration are political factors in the home country, including a reduction in human-rights violations and the end of genocides/politicides and wars, together with peace agreements. Economic incentives were found to be a relatively weak motive for refugees’ return, while relative structural conditions in home and host countries were important. Access to education, which combines economic and social aspects, was also an influential factor.

A growing body of qualitative research has highlighted the significance of contextual factors in shaping return intentions and actual return decisions among migrants (Al Husein and Wagner 2023; Kunuroglu, van de Vijver and Yagmur 2016; Tezcan 2019). Studying Ukrainian refugees in Norway who left the country after a relatively short time is particularly relevant for the study of voluntary return as it can provide nuances to established theories on refugee return migration. According to existing models, political stability and the cessation of conflict are among the strongest predictors of return. However, in our case, Ukrainians are returning voluntarily despite an ongoing war, making it reasonable to explore other factors driving their decisions that outweigh security concerns.

We apply Koser and Kuschminder’s (2015) framework by examining how structural, individual and policy-related factors in both home and host countries interact in this unique case. The study provides an opportunity to explore the role of host-country conditions, such as Norway’s temporary protection policies, labour-market access and social integration, in shaping return decisions. Furthermore, Zakirova and Buzurukov’s (2021) finding that economic incentives are weak predictors of return migration raises important questions about whether Ukrainian returnees and onward movers are more motivated by social and psychological factors than by economic opportunities.

A useful lens through which to understand the motivations behind return migration, particularly among refugees, offers Albert Hirschman’s (1970) framework on exit, voice and loyalty. While much research focuses on exit (migration) and voice (political expression), loyalty – defined as a commitment to a collective even under adverse conditions – may also help to explain return decisions. Loyalty in this context can manifest as a sense of duty or moral responsibility to the home country. These motivations may not be easily captured by standard economic or security-based models of migration decision-making but are highly relevant in the case of war-related displacement.

Belonging and transnational ties after leaving Norway

Our second research question asks whether displaced Ukrainians have formed persisting emotional or network ties to Norway during their stay in the country. We investigate whether ties to Norway and Norwegians endure beyond departure, even among those who leave relatively quickly, as is the case with the participants in our study. To examine the presence and nature of such ties, we employ theories of transnationalism and belonging.

Transnationalism theory emphasises the presence of social networks that extend beyond national boundaries (Vertovec 2009). It highlights the concept of multiple belongings, suggesting that individuals may feel connected to more than one place or community (Cheran 2006). Although previous studies often use this framework to reflect on the practices of labour migrants or diaspora members, Al-Ali, Black and Koser (2001) conclude that refugees are engaged in a wide range of transnational activities, inviting them to be included within the framework of transnationalism. Refugees often maintain strong ties with their country of origin even while residing in a host country – but connections to the host country can also develop among those returning or moving onwards. Like other migrants, refugees may experience complex feelings of attachment to their home country, their host country and sometimes even third countries. Such nuanced senses of belonging could not only impact on decisions regarding return or onward movement but could also potentially influence ongoing affiliation with a previous host society. Some departing individuals may even consider returning to their previous host society, in our case Norway, at a later stage.

Transnational activities are often categorised as economic (especially remittances), socio-cultural (keeping in touch with relatives abroad and visits) and political activities (political-party membership, voting, lobbying and civic activities). However, there are fewer studies on the emotional aspects of transnational lives (Kemppainen, Kemppainen, Saukkonen and Kuusio 2022). Some studies have approached transnational belonging from the perspective of emotional attachment and imaginative practices (Klok, van Tilburg, Suanet, Fokkema and Huisman 2017). Imaginative transnational belonging can include nostalgia and longing for one’s country of origin, as well as the desire to return. Conversely, we hypothesise that Ukrainian refugees who have returned to Ukraine may experience an imaginative transnational belonging to Norway and seek to identify how they frame this in terms of their future plans.

Studying the transnational activities – or the readiness to realise them – in the case of Ukrainian refugees with collective protection is heuristic from several perspectives. Firstly, it provides an understanding of transnationalism from a short-term perspective, as previous research on transnational networks has tended to focus on migrants who have long-standing ties with the host country (Nuga 2024). Secondly, we interview people who have returned to their home state or moved onwards, while most previous research has focused on people still living in a host country. Thirdly, a newly conducted study on Ukrainian refugee experiences in Germany highlights that, due to the multiple uncertainties determined by the temporality of collective protection for Ukrainian refugees in Europe, transnational ties have become a type of coping strategy through which to overcome the unknown future (Lapshyna 2025). This brings new practical meaning to the transnationalism framework in light of the ‘temporary turn’ in contemporary integration policies (Sandberg, Schultz and Syppli Kohl 2025). Finally, we examine networking with Norway through a future-oriented lens, considering whether these attachments, sense of belonging, identity and social capital could be converted into future plans for continued contacts – for example, via labour migration.

Do transnational activities ensure a sense of belonging and emotional attachment to both home and host countries? How does the decision to return influence them? For refugees and displaced people, multiple attachments often hold heightened significance as they navigate the intricate intersections of their past, present and future lives. Yet transnational ties to a previous host society may also persist without much sense of emotional attachment (Youkhana 2015; Yuval-Davis 2011).

Refugees and displaced people may grapple with questions of belonging as they navigate between their country of origin, their current host country and third countries. Antonsich (2010: 644) posits that belonging should be analysed ‘both as a personal, intimate, feeling of being “at home” in a place (place-belongingness) and as a discursive resource that constructs, claims, justifies, or resists forms of socio-spatial inclusion/exclusion (politics of belonging)’. Home-studies literature offers various perspectives on refugees’ feelings of being ‘at home’ in a place. Dossa and Golubovic (2019) argue that displacement complicates the comprehension of what it means to be at home. Recent studies on the concept of home, such as that by Boccagni (2022: 585), reframe it as a matter of ‘homing’, evolving from viewing ‘home as a place’, through ‘home in the making’, to a novel understanding of ‘home as becoming’, thus reconsidering home as a social process rather than a place or state.

Although European countries vary in how they receive displaced Ukrainians, in most cases Ukrainian refugees do not stay in refugee camps for years; registration and settlement occur more quickly (Hernes et al. 2023a), thus helping them to avoid the ‘campisation’ often experienced by other refugee groups who are granted individual asylum. This generally improves their chances of successful home-making practices, fostering a stronger sense of belonging to the host state. On the other hand, collective protection introduces a sense of temporariness, which can hinder the establishment of a sense of home in the host country due to the looming thought of being sent home. Integration challenges experienced by Ukrainian refugees in European countries should also be mentioned as one of the barriers that hinders home-making and belonging in the host countries (Deineko and Aasland 2024; Kosyakova, Gatskova, Koch, Adunts, Braunfels, Goßner, Konle-Seidl, Schwanhäuser and Vandenhirtz 2024). The perspective of transnationalism allows us to examine Ukrainian refugee homing beyond the ‘here and there’ dichotomy (as described by Taylor 2013), suggesting a framework of multiple belongings (Deineko and Aasland 2024).

Remaining family members in Norway, friendships established while residing in the country and economic and professional ties serve as examples of potential links that do not necessarily involve sentiments of belonging. We explore whether and how displaced Ukrainians who have left Norway have developed an emotional attachment and sense of belonging to the country from which they departed, together with their potential involvement in transnational activities involving Norway that do not necessarily include any strong emotional ties to the country.

Data and methods

The article builds on 8 qualitative semi-structured interviews conducted in the winter of 2024 with Ukrainians who fled to Norway after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 but who later voluntarily left the country. We recruited the interviewees via online surveys that were conducted among Ukrainian refugees in Norway in 2022 and 2023, in which respondents were asked if they were willing to leave their email addresses so that they could be contacted for follow-up interviews (for the methodology of the surveys in Norway, see Hernes, Aasland, Deineko, Myhre, Liodden, Myrvold, Leirvik and Danielsen 2023b).

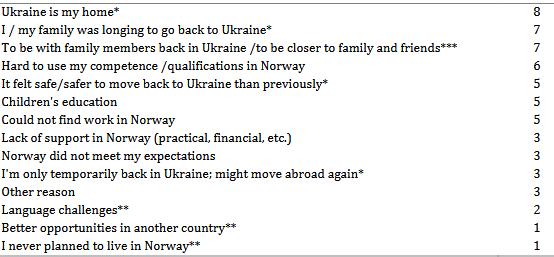

When the 2023 survey was conducted, some of those who had shared their email address in the 2022 survey had already moved back to Ukraine or on to another country, providing an opportunity to ask them about their reasons for leaving in a separate section of the survey. A total of 21 respondents who had already left Norway responded. This sample is too small to make firm conclusions about reasons for leaving but it can be illustrative of important trends, as also demonstrated by IOM (2025) statistics (see Table 1 for an overview).

The EXIT-Norway project is particularly interested in understanding what characteristics of Norwegian society lead immigrants to leave the country.3 With the substantial influx of Ukrainian refugees to Norway, we recognised that exploring the interplay of motivations for leaving among a recently arrived group whose home country remains at war could provide valuable insights into why forced migrants choose to leave a host society renowned for its highly developed welfare system and generous reception environment for refugees.

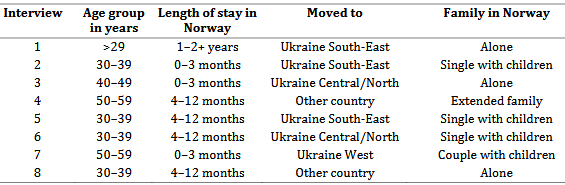

A request was sent by email to respondents who stated in the survey that they had left Norway. Online interviews on Zoom were arranged with 8 such respondents. Six of them had left for Ukraine and 2 had moved on to other Western countries. The interviews lasted around 40–60 minutes and were conducted in Ukrainian and transcribed using Autotext (Whisper), with immediate checks for quality. They were then anonymised4 and coded in Nvivo.

Table 1. Main reasons indicated for leaving Norway (N=21)

Notes: *Option only for those who had returned to Ukraine;

** Option only for those who had moved to another country;

*** Wording of question adjusted to context but merged.

With its small number of interviewees, we acknowledge important limitations to our study. We do not assert that our qualitative findings achieve saturation in terms of elucidating all the reasons behind people’s decisions to return to a war-torn Ukraine or choose alternative destinations. It should also be noted that all our interviewees were women. Thus, our findings cannot be used to make firm generalisations about why people return or move onwards.5 However, while our survey responses (Table 1) only provide a broad overview and illustration of displaced Ukrainians’ motivations for leaving Norway, we contend that our semi-structured interviews with a subset of these respondents add relevant nuance by yielding a deeper understanding of personal experiences and perceptions. The findings therefore contribute valuable insights into the intricate interplay of factors that ultimately shape emigration outcomes. Key characteristics of the interviewees are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Key characteristics of interviewees

The Norwegian reception of displaced Ukrainians

Norway is not part of the EU nor bound by the EU’s Temporary Protection Directive. Nevertheless, after Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the country introduced legislation that mirrored the directive in most respects. Persons granted collective protection in Norway received a residence permit for 1 year, with the possibility of extending it for up to 3 years. Although there are many similarities between European countries receiving displaced Ukrainians, there are significant differences in the rights, services, benefits and integration measures they provide (Hernes et al. 2023a). Norway has provided displaced Ukrainians with similar rights to those of other protection-holders, including financial assistance and integration measures. Individuals with temporary protection can work, reunite with family and have access to kindergarten, education and healthcare services. People under the age of 55 have a right – but not an obligation – to attend the Norwegian Introduction Programme, which includes language training, work experience and informational elements. Participants receive generous benefits while attending.

Research has shown that, overall, Ukrainians have been very satisfied with their reception in Norway (Hernes et al. 2023b). However, concerns have been noted regarding services and assistance in job-seeking (Hernes et al. 2023b: 63–64). The Norwegian authorities have increasingly stressed that displaced Ukrainians should enter the labour market faster, as participation rates are currently lower than in neighbouring countries. They further emphasise that the stay is intended to be temporary, with the goal of return when conditions in Ukraine improve. After our interviews were conducted, the authorities also introduced certain restrictions to reduce the number of new arrivals (Aasland 2024).

Results

Family and children as a main exit factor

Research has shown that migration decisions are usually made by the entire household and take the interests of all family members into consideration (Massey, Arango, Hugo, Kouaouci, Pellegrino and Taylor 1993). In most contexts, if the family does not migrate as a unit, it is usually the male representative who migrates first. In a Ukraine at war, the situation has been the opposite. Due to restrictions on male migration, refugees from Ukraine, especially after the full-scale Russian invasion, were predominantly women. As a general rule, men aged 18–60 are not allowed to leave the country under martial law (Deineko and Hernes 2024).

Several of our interviewees mentioned family concerns as their reason for leaving Norway, in particular the presence of close family members who had remained in Ukraine. These family members could be husbands: ‘Well, the main reason why we left Norway was (…) that my husband stayed in Ukraine’ (Interview 6) but they could also be adult sons who were unable to leave the country. Some interviewees also mentioned elderly parents who needed care as a contributing factor in their decision to return. Such reflections on returning included both emotional and practical aspects of the family living separately. In a few cases, relatives remaining in Ukraine could exert indirect or direct pressure on the displaced people to return. For example, one interviewee’s elderly mother, who was in poor health, urged her daughter to come home, a request that had been difficult to ignore. Several interviewees explicitly stated that they would probably have stayed in Norway if the whole family had been able to be together.

While research on displaced Ukrainians in Norway has shown that most children adapt well into Norwegian society and rapidly integrate into Norwegian schools (Hernes et al. 2023b), this is not the case with all Ukrainian children. Among our interviewees, there were several accounts of children finding it difficult to make Norwegian friends, leaving them feeling isolated, being bullied and even unwilling to attend Norwegian school:

So, they [her previous friends] started to leave her and she stayed alone during school breaks and went home alone. Somehow the boys from the parallel class also began to get annoyed with her. She wears glasses and they took her glasses case and began to throw it around. She was very upset and said, well, she wouldn’t go to school any more (Interview 5).

According to the mother, the consideration for this child was the main reason for returning to Ukraine. Parents sometimes needed to make difficult choices for their children about returning to a much-less-secure environment in Ukraine, with occasional Russian attacks but in a setting where they believed their children would be more likely to thrive:

So, I came back to Ukraine, saw how strong she [her daughter] was here, well, there was shelling, when we were there for New Year (...) but the air defence still works, well, I just looked at it this way. (...) I understand she’s a child and she doesn’t make decisions but, for her psychological state, she needed it [to go back to Ukraine] (Interview 6).

Several returnees and onward movers interviewed still had family members staying in Norway. For some, this meant that they were eager to visit Norway again so that they could be together.

Work prospects as a structural reason for returning

The interviewees mentioned various work-related challenges as factors contributing to their decision to move, with some highlighting them as their main reason for departure. Work was an important push factor for leaving, as several interviewees saw no prospects of finding relevant work in Norway.

A few were discouraged from the start by perceiving – or being told – that it was hard to find a decent job in Norway without speaking Norwegian or English. Such information was given by the interviewee’s contact person in the municipality or by the local social-welfare/employment agency Nav. One interviewee said: ‘We were told that it was impossible if you did not know English or Norwegian’ (Interview 8). She had done some online remote work with clients in Ukraine instead. The Introduction Programme offered to Ukrainian refugees, which aimed to qualify them for jobs in the Norwegian labour market, was not seen as attractive by all interviewees, since it would take time to qualify for a proper job:

Somehow it was said that you have to go on this [Introduction] programme to study. It was a year. I said: ‘I’m sorry, but I cannot go to school for a year, I’m already of such an age’. I asked: ‘Can I work somewhere and study [in parallel]?’ Well, no, there, well, somehow it was said that I couldn’t. I then said: ‘I don’t have time (...) to spend a whole year at school’ (Interview 3).

Competition with native Norwegians or immigrants from EU countries for the same jobs was also mentioned as an obstacle:

[I] applied for a job at a kindergarten. But then, when I had a meeting with the director of the kindergarten, she told me that it all depends on whether there will be any more Norwegian applicants for this position. Because first they will consider them, then those people who have a European citizenship, the EU and then us. So, that was the problem. So, again, I was simply not invited to the internship (Interview 1).

For those being settled in a rural area, a lack of relevant workplaces could be a major challenge. One interviewee who found a part-time job in a fish factory was dismissed due to layoffs and could not find other work in the municipality. She believed that if she had continued to work there, she would have stayed in Norway, as she still had family there:

In November [2022] I was dismissed, well, since they laid off many workers, those who were temporary workers and that includes me. They just told me one day that ‘That’s it, we don’t need your services’. But if I’d kept this work at the factory, maybe I would have stayed and worked at the factory and we would have all been together as a family. Because now I miss it [Norway] a lot (Interview 4).

Others were concerned about finding a job where they could use their previous education or qualifications in Norway. The uncertainty about staying in Norway when their temporary protection expired made some question the utility of investing in a new career path. Changing a profession can be challenging for someone with long work experience. One interviewee, who reflected on her future options during a brief trip to Ukraine, decided to return:

And when I looked at all this, I realised that now I either need to go to Norway for a new profession or to be dependent on money from the state – which I didn’t want at all – or I go back home to Ukraine (Interview 1).

The refusal to live on social benefits was shared by others:

And from September [2022] onwards, let’s say, I didn’t have the conscience to take these social payments, these 600 kroner they paid us. I understood that I want more and I can work – but there’s simply nowhere to work (Interview 4).

Strict labour-hiring legislation in Norway was also mentioned as an obstacle:

I even wanted to pick strawberries, there, along the road (...) Well, he didn’t hire us. We went, asked, he said, ‘No, for legal reasons you cannot work here’. The country is quite legal, so... (Interview 3).

For others, work obligations and opportunities in Ukraine were major reasons for returning. With only temporary protection in Norway, Ukrainian refugees must also consider the possibility of returning in the future, making job prospects in their home country a relevant concern. A dilemma may arise if, for example, a previous employer requires an emigrant’s immediate return to retain a position in Ukraine, as was the case for one interviewee who had worked at a children’s centre but left soon after the full-scale invasion:

First, they closed down the centre. But our director reopened it, it started running but then I left for Norway. She wrote to me all summer [2022] saying that I should return, because there was lots of work, many children were returning; she said I had to work, that I should return. And so, probably, she also played a role in my decision to leave [Norway] (Interview 5).

Having job prospects in Ukraine or a third country was a decisive factor for several interviewees, as one who had returned to Ukraine explained:

There was still a problem with work. Because I was sent to work practice without any problems but, when there was a question about permanent work, unfortunately, I was refused. And the only thing my curator6 could offer me was to go to university, to change my profession. [...] I continued to work online, working with Ukraine. I knew that I had a job to go back to. I didn’t have such a dead-end situation (...). I knew that I could find a job but, in Norway, with my background, it was difficult in this regard (Interview 1).

The Norwegian health system as a reason for leaving the country

The Norwegian health system is characterised by universal coverage, providing comprehensive healthcare services to all residents, including displaced people from Ukraine who have the same rights to healthcare services as Norwegian citizens. However, healthcare is an area where displaced people from Ukraine have had mixed experiences in Norway. A ‘culture clash’ has been observed between the Norwegian and Ukrainian cultures, for example regarding the threshold to see a doctor or a specialist and access to or use of medication (Hernes et al. 2023b).

Negative experiences with the Norwegian healthcare system was a recurring theme when interviewees were asked about their experiences in Norway and their reasons for moving. One of the interviewees put it like this: ‘In Norway you need to take maximum care of yourself. If you’re Ukrainian, you need to take a hospital with you’ (Interview 6). Many saw the system involving a mandatory consultation with a general practitioner (fastlege) before referral to a specialist as a serious obstacle to obtaining necessary medical treatment. The role of the healthcare system in the decision to return to Ukraine is illustrated by the following statement:

One reason was my health, because I started having back problems – it was very difficult for me to walk. I went to my general practitioner in Norway. (...) As he explained to me, I didn’t have any serious symptoms. (...) Unfortunately, he couldn’t refer me to a specialist and when I came back [to Ukraine], it turned out that I had a hernia in my back. (...) So my healthcare experience wasn’t good. (...) I got used to, for example, my doctor in Ukraine always being in touch with me, I could call him if something happened. (...) This is also one of the reasons why I moved [from Norway] (Interview 1).

For others, healthcare was not given as a main reason for leaving but something that would have been difficult to adapt to had they stayed on:

Yes, thank God we didn’t get sick but my children hit my finger with a stone when the kids were playing – and very hard – so that my finger got injured. (...) It should have been thoroughly disinfected or even an X-ray taken, in my view. But when we arrived at the hospital, they just looked, they didn’t even disinfect it, they just glued it with some cream and that’s it. It was really weird. And it’s also good that we’re back home, because it was quite scary for us (Interview 2).

One of the interviewees who had moved on to the US praised the health insurance that she had access to there; she compared the US favourably to Norway:

Another question is about the availability of healthcare. When we arrived [in the US], the first thing we received was health insurance, which the state gave us for free. In Norway, well, let’s say, this wasn’t possible. I lived [in Norway] for almost a year. I got sick once, a severe fungal infection developed and it was very problematic. That is, you first had to go to the general practitioner and, as for specialists, I won’t even talk about it [...]. So in this regard, America is much better (Interview 4).

One of the few interviewees who expressed satisfaction with the healthcare system in Norway underlined the differences between the cultures in the 2 countries in terms of when a visit to the doctor is deemed necessary:

Well, I had a very pleasant impression of the medical system, because I didn’t wait in a queue anywhere; maybe there was no such crowd of people, influx, everything was very clear. I’ll tell you honestly, I don’t go to doctors, I’m like Norwegians, (...), I treat myself with water. I like that country [Norway] in this respect, I could very well live there, I don’t need to take an X-ray straight away (Interview 3).

Altruistic reasons and expressions of loyalty

Some interviewees cited societal benefits as a significant or contributing factor in their decision to return to Ukraine. This included, as mentioned, a desire not to burden Norwegian society and taxpayers. Our focus here, however, is on their wish to contribute to Ukrainian society. Two main arguments emerged from our interview data.

The first argument is the recognition that people from territories occupied by Russia or areas close to the frontline are in more-urgent need of protection than those in less-affected areas, such as the western part of the country. At the beginning of the war, the situation was unpredictable and many feared a total Russian occupation of Ukraine. Now, some perceive the situation as somewhat stable, recognising that certain areas of Ukraine are under less immediate threat. This implies that, while no part of Ukraine is completely safe, some areas are safer than others. As such, some felt that it was now safer to return and did not want to exploit the asylum system by taking up resources that could be used for people from Eastern Ukraine whom they felt were in greater need:

There’s no safe place in Ukraine now. And we had bombings literally 200 metres from our house. But our situation is not as catastrophic as in Eastern Ukraine. My daughter and I decided that we wouldn’t take a place from people from the East and that we would bring more benefit to Ukraine. That’s our story (Interview 7).

The second argument is the belief that, despite the potential for a better economic situation and greater security in Norway, the most important task is to support and rebuild a war-torn Ukrainian society:

In Norway, I would just sit there, receive something. Maybe if I’d stayed, I would have had more and better food, maybe something else would have been better than now. Yes, there wouldn’t be alarms several times a day. But what good am I in Norway? None. And here I feel like I bring a lot of benefit. (…) If we all move and everyone just sits and waits for someone to do everything, I don’t think that’s the right approach. I feel like I’m on the right path, doing a lot of useful things for my country. It’s my contribution to victory (Interview 7).

Thus, some people’s decision to return to Ukraine is driven by a sense of duty to their country and a desire to make a meaningful contribution to its recovery and future.

Attachments to Ukraine and Norway: Leaving Norway, keeping transnational connections

From the survey (Table 1), we saw that attachment to Ukraine could be a main reason for return. This was also highlighted by our interviewees, who explained that Ukraine – or their home town – was their home and that their life in Ukraine had been good:

Before the full-scale invasion – and even after – I didn’t want to leave. I always wanted to live in Ukraine (...) I always had a feeling that [home town] was my home and I didn’t want to move at all. I could go anywhere with my language skills (...). I lived in [other] countries a bit but Ukraine was still my home and I wanted to build my life there (Interview 1).

Interviewees also expressed a strong emotional attachment to Ukraine and their place of living when the full-scale invasion took place, consistently considering it their true home despite safety considerations and the amenities available in Norway. This includes the two interviewees who moved onwards from Norway to other countries but still hoped to go ‘home’ to Ukraine in the future, despite the practical hurdles.

While emotional attachments to Ukraine were strong among all 8 interviewees, responses were mixed when asked whether they had built an attachment to Norway or Norwegians. Though Norwegians were commonly referred to as friendly, helpful and welcoming, only a few interviewees had developed deep friendships with Norwegians during their stay. Language challenges might have been a reason for this. Our interviewees appreciated what they described as a Norwegian welcoming attitude towards displaced Ukrainians. One interviewee shed tears while explaining how complete strangers had approached her and her children with material and emotional support, while another described how her landlord had filled up her family’s fridge and provided them transport on different occasions. However, a few interviewees had negative experiences with Norwegians and Norwegian culture. This involved a feeling of being culturally disconnected, finding Norwegians colder and less open to deep friendships. Differences in cultural codes were also mentioned – for example, when to invite friends home – making it difficult for some to connect with Norwegians.

While the displaced Ukrainians in our study had all left Norway and had varied experiences with Norwegians and Norwegian culture, it was striking to find that most maintained some connection with the country. Some even expressed an intention to return, particularly those who reunited with family members, such as husbands or sons, back in Ukraine. They might consider returning once the war ends, or if the restriction preventing Ukrainian men aged 18–60 from leaving the country is lifted.

Although some interviewees explicitly stated that they did not wish to remain in Norway as refugees dependent on the welfare system, they were open to returning as labour migrants. Their motivations varied: some felt that Norway offered a more-secure future than war-torn Ukraine, while others felt a sense of gratitude toward a country that helped them in a time of need: ‘I simply want to thank them for everything they did for us. I would gladly work there [to] show my appreciation’ (Interview 3).

Norwegian nature was mentioned as an important asset and was even highlighted as the factor they liked or missed the most about Norway and a main reason why they felt ‘at home’ in the country: ‘I felt at home there. Especially the nature. Everything is nice there. And I have a love for nature’ (Interview 2). Comfort was found in natural landscapes in Norway reminiscent of those in their home district or parts of Ukraine with which they were familiar. Interviewees described how the Norwegian nature, mountains and sea helped them to relax and heal their worries about the war.

While only a few interviewees were seriously considering a permanent return to Norway, most emphasised other ways of maintaining contact with the country, often through digital means:

I still keep in touch with Norway, with my friends who were there. I talk about how much I miss Norway, its vastness, its nature, its quiet, measured life. It was close to me because that’s how I lived at home. It was comfortable for me (Interview 4).

Language played a role in Ukrainian refugees’ decisions as well. One interviewee stood out as she continued studying Norwegian even after returning to Ukraine, hoping that her improved language skills would boost her chances of later finding work in Norway that aligned with her previous education and qualifications.

Even a short stay in Norway could leave an imprint and some of the interviewees noted that they had started to behave in a more ‘Norwegian way’ after returning to Ukraine, as shown in the following statement:

They’re very friendly; we’re always a bit more serious people. It was unusual at first but I got used to it. When I came home to Ukraine, I also smiled at people and the security guards in the store looked at me with suspicion as if something was wrong. Secondly, what I like about Norwegians, if you have a day off, you have a day off. (...) I’m trying to do that now. A slightly slower pace of life. You could call it that. And we [Ukrainians] always (...) hurry somewhere. We need everything fast, fast, fast (Interview 1).

This shows that they had learned and incorporated some Norwegian ‘cultural codes’ in the course of their short stay in Norway, providing additional grounds for maintaining a sense of belonging and transnational ties with the country.

Discussion

Structural, individual and policy factors as reasons for return

To answer our first research question, we return to Koser and Kuschminder’s (2015) typology. Our findings suggest that combinations of structural, individual and policy factors in both home and host countries are important for refugees’ decisions to leave after a relatively short time. While this is likely to be the case with most refugee departures, we would argue that both the temporality of Ukrainian refugees’ protection and particular factors in the Norwegian context add nuances to the literature on refugees’ rationale for leaving a highly developed welfare society such as that of Norway. In this article, we have particularly focused on how conditions in the host country contributed to the decision to leave.

Although our sample is too small to make generalisations, the lack of prospects of long-term employment appears to play a crucial role among the structural factors. With limited command of the local language, it was difficult for our interviewees to find a job where they could utilise their previous qualifications. It is also striking how several of the interviewees gave up looking for work after receiving discouraging information about job prospects from their contact persons in the municipalities or from other public services. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the Norwegian system of dispersing displaced Ukrainians to districts with limited or one-sided labour markets may reduce work opportunities for well-qualified individuals. For persons with better job prospects in Ukraine – or in other countries – leaving Norway was therefore considered a better choice.

Surprisingly, the Norwegian welfare state was rarely considered as a reason for remaining in the country. The healthcare system in particular was more often considered a reason for leaving than for staying, explained by its perceived low quality and untimely access to services. Furthermore, several interviewees expressed a desire to avoid long-term dependence on welfare and would only stay in Norway as contributors and taxpayers. Some even considered returning to Norway if they could join the labour force, viewing this as a way of showing gratitude for the country’s support during their time of need.

It is notable that structural factors in the host country which, according to the literature, are often associated with refugee return, were not given by our interviewees as reasons for leaving Norway. They were generally satisfied with the economic support and other public welfare services offered, including housing provided by the municipalities in which they were settled. They were also largely satisfied with the Norwegian reception system for refugees and with the rules and regulations regarding protection (interviews were conducted before restrictions had been introduced). None of the interviewees talked about general anti-refugee sentiments or discrimination. With only one exception, they did not perceive any hostility from the host population that made them feel unwelcome – quite the opposite. Nevertheless, language barriers were raised not only as a concern when it comes to finding a job but also as an obstacle to closer social integration with Norwegians.

Family considerations were found to be of great importance, with keeping the family together often outweighing both security and welfare concerns associated with leaving Norway. Homesickness was also a common sentiment that played an important role in the interviewees’ decision to leave. Furthermore, they emphasised that the decision was made collectively as a family, taking into account the interests of all family members, both in Norway and Ukraine, which prompts us to suggest that familial factors should be added to the individual factors in Koser and Kuschminder’s (2015) typology. For some interviewees, their children’s struggles with social and school integration in Norway were significant reasons for returning to Ukraine. Opinions on Norwegian schools were mixed, particularly regarding the level of freedom given to children. While this freedom was seen as beneficial for children’s well-being, it was also perceived as a potential obstacle to learning. Additionally, it is noteworthy that interviewees expressed altruistic and patriotic motivations, believing that their return would both create space for more vulnerable refugees and allow them to contribute to the rebuilding of a war-torn Ukraine.

The final component in Koser and Kuschminder’s (2015) typology is policy interventions. The most obvious policy restrictions for return are restrictive immigration and asylum policy and various forms of legal uncertainty. Such factors also played a role for our interviewees’ decision to leave Norway, although more indirectly than directly. Our interviewees left long before the temporary protection status had expired and they remained free to either stay or leave. The minimal financial support from the Norwegian state that refugees receive if they decide to return was barely mentioned by our interviewees unless prompted, so it appears to have played a very minor role in return decisions. The Ukrainian authorities had not established a programme for returnees but the knowledge that staying in Norway would necessarily mean investment in language, work and social integration, without necessarily leading to a long-term solution, makes the uncertain legal status a highly relevant aspect of decisions to leave. While legal uncertainty may not have been the primary trigger for return, it shaped the broader context in which decisions were made, reinforcing other factors that ultimately led to departure.

It should also be noted that the recent measures introduced by Norway to restrict Ukrainian refugees’ access to temporary protection could contribute to the impression that Norway may eventually implement policies aimed at forcing Ukrainian refugees to leave. Further research is needed to determine whether such policy changes are prompting Ukrainian refugees currently in Norway to reconsider their future plans.

Leaving Norway – keeping connections?

To answer the second research question on whether displaced Ukrainians who have left Norway developed emotional or network ties to the host country, we return to the prism of transnationalism and belonging.

Our study highlights that those who returned to Ukraine had strong emotional attachments to the country, while their experiences with Norwegians and Norwegian culture varied. It is worth mentioning that most have maintained some connection with Norway and its people – and even experience nostalgia. Most of our interviewees continued to maintain regular contact with displaced Ukrainians they had met in Norway, whether in reception centres or municipalities. Some also stay in touch with Norwegians, often landlords or welfare workers, such as refugee-service contacts or school-teachers. While few reported forming lasting friendships with Norwegians, suggesting that such relationships were less common, we assume that these experiences are an important factor in establishing further transnational activities. Since Ukrainian refugees in Norway spent minimal time in reception centres and were able to live privately with family or friends, they were settled relatively quickly (Hernes et al. 2023b). This allowed them to enhance social ties at the local level from the onset. Their integration began earlier and engaged previously less ‘visible’ actors who play a significant role in refugee integration during the initial period in Norway, such as private hosts, diaspora members and NGOs. These new structural conditions have created pathways to transnational connections and attachments for those who decided to return.

The results of our study are difficult to compare with previous research in this field (Al-Ali et al. 2001; Kemppainen et al. 2022; Klok et al. 2017), as we interviewed individuals who were in the host state for a short time and had already returned to Ukraine. However, we identified features of imaginative transnational belonging through informants’ reflections on Norwegian nature, nostalgia for Norway and a desire to return in the future as tourists or labour migrants. Some interviewees had even learned and incorporated Norwegian ‘cultural codes’ into their habits and behaviour patterns, providing additional grounds for maintaining a sense of belonging and transnational ties with the country.

Ranging from family relationships to friendships and potential employment opportunities, often rooted in a deep appreciation for the country, our findings on the continuation of links to Norway reveal both the prevalence and the diversity of these connections. Personal circumstances, such as family situations and individual experiences in Norway, significantly influenced the sense of belonging and the likelihood of maintaining ties to the country. This underscores the need to consider individual and family dynamics when discussing transnationalism and belonging.

Conclusions: Future prospects of exit among displaced Ukrainians in Norway

Although relatively few displaced Ukrainians have so far decided to leave Norway after being granted collective protection, it is expected that many more will eventually return, both voluntarily and, possibly, involuntarily in the future. People’s motivation to leave Norway at the initial stage of integration offers valuable insights and feedback regarding both integration policies and key factors that determine the desire to leave a highly developed welfare society and return to a country still at war – or to make a future in a different country.

Our article has shown the significance of an interplay of individual, structural and policy-related factors in explaining displaced Ukrainians’ desire to return to Ukraine. Perceived social obligations to take care of relatives, family members left in Ukraine and the social well-being of children appear to play a decisive role. These factors even outweighed the security concerns and numerous risks to life during wartime, as interviewees also moved back to areas of Ukraine frequently targeted by shelling. Although in many contexts, as shown by Zakirova and Buzurukov (2021), political factors in the home country – especially the cessation of war and security issues – are the most important reasons why refugees return, they were not significant among our interviewees. It is reasonable to assume that this is in part because all of our interviewees were women who are still traditionally ‘care persons’ in their families and are not subject to military service.

We see that family situation and loyalty play more significant roles in this regard. Our study highlights that some people’s decision to return to Ukraine is driven by a sense of duty to their country and a desire to make a meaningful contribution to its recovery and future. These motives align closely with Hirschman’s (1970) loyalty concept – a willingness to remain committed to a group or nation despite hardships. In this context, loyalty implies choosing to return rather than pursuing a permanent exit. In our data, this form of loyalty is expressed both as an altruistic concern for others in greater need and as a personal commitment to rebuilding Ukrainian society.

Unlike other refugees, who are often unable to return to their homeland due to political persecution, displaced Ukrainians maintain close connections with their networks in Ukraine and have the possibility of returning to Ukraine with no political restrictions. As such, their belonging to Ukrainian society is more sustained over time. Paradoxically, for some of the displaced people, political motives regarding the war situation were a main reason for returning to Ukraine rather than for staying in Norway. Despite the potential for a better economic situation and greater security in Norway, the desire to support and rebuild a war-torn Ukrainian society and to allocate ‘refugee benefits’ to those in greater need (such as Ukrainians from the eastern regions or the front lines) influence their decision to go back.

Our study proposes a ‘paradox of leaving’ that characterises the return and onward migration of Ukrainians from Norway and which should be studied also in the context of emigration from other welfare states. Although the Norwegian healthcare system, with its universal coverage and comprehensive services, could logically be seen as an asset for staying, cultural patterns and familiar approaches to medical treatment from Ukraine in fact contributed to several of our interviewees’ decisions to leave. This demonstrates that there are no universally defined and stable factors influencing a decision to stay or leave; rather, subjective perceptions and previous social experiences play a crucial role. Although this paper does not provide a detailed conceptualisation of the ‘paradox of leaving’, we emphasise that this phenomenon can enhance our understanding of the mismatch between expectations and realities in host welfare societies. It offers insight into factors that influence refugee mobility beyond the traditional push and pull dynamics.

Additionally, the study has shown that certain stereotypes and ‘limiting beliefs’ prevalent in public discourse and refugee perceptions can significantly hinder integration efforts. In our study, a common belief that ‘it is impossible to find a job in Norway’ exemplifies this. Stories from our interviewees indicate that this belief was often accepted as a given, discouraging them from even attempting to find employment and thus impeding their social agency and pressing their return to their home country.

From an individual perspective, our study reveals that the traditional dilemma of whether ‘to stay or to go’ can be far more complex within each family than it would at first appear. One child may thrive in Norway, for example, while another may suffer and desperately wish to return to Ukraine. This highlights the variety and heterogeneity of integration outcomes, particularly concerning children, which complicates each unique case, destiny and life.

Although we should be careful when generalising based on a small number of interviews, an important finding is that Ukrainian refugees who decide to return home or move onwards to another country tend to adopt a transnational approach and maintain multiple attachments even when their stay in the host country has been somewhat brief. Although our study did not focus deeply on unpacking place belongingness (the feeling of being at home for refugees), it provided evidence of ‘creating home’ in Norway through social surroundings and ties, even in a short-term perspective. We also noted emotional attachments and feelings relating to Norway, Norwegian society and Norwegians in the interviewees’ narratives, associated primarily with gratitude towards locals’ support and care, which could potentially enhance transnational ties and maintain a sense of belonging at the individual level in the long term. Meanwhile, Norwegian ‘politics of belonging’ (Antonsich 2010) remain quite controversial, offering displaced Ukrainians opportunities for short-term inclusion into Norwegian society (via the introduction programme and work opportunities) while simultaneously signalling the expectation of return to Ukraine when conditions so permit.

The temporary nature of collective protection and Norwegian policy documents, such as the white paper on the Nansen support programme (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2024), speeches by Norwegian decision-makers and restrictions on collective protection regulations, indicate that many Ukrainian refugees in Norway may eventually be obliged to return to Ukraine (Aasland 2024). However, our study suggests that this decision may not permanently end their potential continued link to Norway. The social capital gained in Norway, along with the knowledge of Norwegian society and language skills acquired by displaced Ukrainians, could facilitate future labour migration. Ukraine’s potential EU integration further enhances the likelihood of such a scenario.

The results of our study provide valuable insights into the ‘temporary turn’ in contemporary migration and integration policies, where temporary schemes and mechanisms are becoming the new norm. Networking with Norway through a future-oriented lens, considering the social attachments and social capital that Ukrainian refugees established during their short stay, introduces new dimensions to prognoses on future mobility.

Notes

- Statistics from UDI (the Norwegian Migration Directorate), https://www.udi.no/en/statistics-and-analysis/ukraina/ (accessed 3 February 2025).

- Updated figures can be found on the UDI’s webpage: https://www.udi.no/en/statistics-and-analysis/ukraina/ (accessed 3 February 2025).

- Project webpage, https://uni.oslomet.no/exitnorway/ (accessed 3 February 2025).

- Ethical approval of the study with an assessment of processing of personal data was obtained from Sikt (Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research), reference no. 261875.

- In a different project (Hernes et al. 2023b), the authors interviewed 47 Ukrainian refugees remaining in Norway. Many of the trends identified among the 8 interviewees in this article are also reflected in these interviews, particularly regarding opinions on the Norwegian healthcare system, labour market and family considerations, thus reinforcing the broader applicability of the study’s findings.

- All Ukrainian refugees who are settled in a municipality are provided with a municipal contact person – or a curator – who is there to assist with various integration issues.

Funding

This article has received funding from the Research Council of Norway (projects no. 313823 and 344219).

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID IDs

Aadne Aasland  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6516-9283

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6516-9283

Oleksandra Deineko  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3659-0861

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3659-0861

References

Aasland A. (2024). Why Ukrainian Refugees in Norway Face an Uncertain Future. LSE Blogs, 30 January. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2024/01/30/why-ukrainian-refugees-in-... (accessed 5 February 2024).

Al-Ali N., Black R., Koser K. (2001). Refugees and Transnationalism: The Experience of Bosnians and Eritreans in Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27(4): 615–634.

Al Husein N., Wagner N. (2023). Determinants of Intended Return Migration among Refugees: A Comparison of Syrian Refugees in Germany and Turkey. International Migration Review 57(4): 1771–1805.

Antonsich M. (2010). Searching for Belonging: An Analytical Framework. Geography Compass 4: 644–659.

Boccagni B. (2022). Homing: A Category for Research on Space Appropriation and ‘Home-Oriented’ Mobilities. Mobilities 17(4): 585–601.

Carling J., Bolognani M., Erdal M.B., Ezzati R.T., Oeppen C., Paasche E., Pettersen S.V., Sagmo T.H. (2015). Possibilities and Realities of Return Migration. Oslo: PRIO.

Cheran R. (2006). Multiple Homes and Parallel Civil Societies: Refugee Diasporas and Transnationalism. Refuge 23(1): 4–8.

De Haas H. (2011). The Determinants of International Migration. Oxford: International Migration Institute, IMI Working Papers Series 32.

Deineko O., Aasland A. (2024). ‘Where is Home?’ Perceptions of Home and Future among Ukrainian Refugees in Norway. Refugee Survey Quarterly 43(3): 347–367.

Deineko O., Hernes V. (2024). The New Mobilisation Act: Policies, Target Groups and Consequences for Ukrainians Living Abroad. Oslo: NIBR.

Dossa P., Golubovic J. (2019). Reimagining Home in the Wake of Displacement. Studies in Social Justice 13(1): 171–186.

Helliwell J.F., Layard R., Sachs J.D., De Neve J.E., Aknin L.B., Wang S. (2024). World Happiness Report 2024. Oxford: University of Oxford.

Hernes V., Danielsen Å.Ø., Tvedt K., Staver A.B., Tronstad K., Łukasiewicz K., Pachocka M., Yeliseyeu A., Casu L., Zschomler S., Berg M.L., Engler M., Nowicka M., Koikkalainen S., Ferdoush M.A., Virkkunen J., Kazepov Y., Berthelot B., Franz Y. (2023a). Governance and Policy Changes During Times of High Influxes of Protection Seekers. A Comparative Governance and Policy Analysis in Eight European Countries, 2015–June 2023. Oslo: NIBR.

Hernes V., Aasland A., Deineko O., Myhre M., Liodden T., Myrvold T.M., Leirvik M., Danielsen Å. (2023b). Reception, Settlement and Integration of Ukrainian Refugees in Norway: Experiences and Perceptions of Ukrainian Refugees and Municipal Stakeholders (2022–2023). Oslo: NIBR.

Hernes V., Aasland A., Deineko O., Handå Myhre M. (2025). Where Does the Future Lie? Initial Aspirations for Return Among Newly Arrived Ukrainian Refugees in Norway. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 51(1): 79–100.

Hirschman A.O. (1970). Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Response to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

IOM (2025). Ukraine Returns Report: General Population Survey [Round 19 Report]. Geneva: IOM.

Kemppainen L., Kemppainen T., Saukkonen S., Kuusio H. (2022). Transnational Activities and Identifications: A Population-Based Study on Three Immigrant Groups in Finland. Migration and Development 11(3): 762–782.

Klok J., van Tilburg T.G., Suanet B., Fokkema T., Huisman M. (2017). National and Transnational Belonging among Turkish and Moroccan Older Migrants in the Netherlands: Protective Against Loneliness? European Journal of Ageing 14(4): 341–351.

Koser K., Kuschminder K. (2015). Comparative Research on the Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration of Migrants. Geneva: IOM.

Kosyakova Y., Gatskova K., Koch T., Adunts D., Braunfels J., Goßner L., Konle-Seidl R., Schwanhäuser S., Vandenhirtz M. (2024). Labour Market Integration of Ukrainian Refugees: An International Perspective. Nurenberg: Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB), Research Report, No. 16.

Kunuroglu F., van de Vijver F., Yagmur K. (2016). Return Migration. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 8(2): 1–28.

Lapshyna I. (2025). Forced Migration, Uncertainty and Transnationalism of Ukrainians in Germany. Mobilities: 1–19. DOI: 10.1080/17450101.2024.2445806.

Massey D.S., Arango J., Hugo G., Kouaouci A., Pellegrino A., Taylor J.E. (1993). Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Population and Development Review 19(3): 431–466.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2024). White Paper on the Nansen Programme (in Norwegian only). https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-8-20232024/id3023633/ (accessed 2 September 2024).

Nuga M. (2024). Transnational and Local Connections in the Integration of Ukrainian Refugee Families. HVL Policy Brief: 1(5)-2024.

Sandberg M., Schultz J., Syppli Kohl K. (2025). The Temporary Turn in Asylum: A New Agenda for Researching the Politics of Deterrence in Practice. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 51(8): 1997–2014.

Taylor H. (2013). Refugees, the State and the Concept of Home. Refugee Survey Quarterly 32(2): 130–152.

Tezcan T. (2019). Return Home? Determinants of Return Migration Intention amongst Turkish Immigrants in Germany. Geoforum 98: 189–201.

UNDP (2024). Human Development Report 2023–24. New York: UNDP.

Vertovec S. (2009). Transnationalism. London and New York: Routledge.

Youkhana E. (2015). A Conceptual Shift in Studies of Belonging and the Politics of Belonging. Social Inclusion 3(4): 10–24.

Yuval-Davis N. (2011). The Politics of Belonging: Intersectional Contestations. Los Angeles, Washington DC and Toronto: Sage.

Zakirova K., Buzurukov B. (2021). The Road Back Home Is Never Long: Refugee Return Migration. Journal of Refugee Studies 34(4): 4456–4478.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.