The Social Integration of Vietnamese Migrants in Bratislava: (In)Visible Actors in Their Local Community

-

Author(s):Hlinčíková, MiroslavaPublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2015, pp. 41-52Views: 18777

The paper examines the integration of Vietnamese migrants through the particular experience of migrants from Vietnam living in Bratislava. From a theoretical perspective, the paper draws upon the research of social anthropologists Nina Glick Schiller and Ayse Çağlar. From a research perspective, it is based on ethnographic interviews and participant observation in a particular neighbourhood in Bratislava where migrants from Vietnam are concentrated. I consider the social relations between migrants and non-migrants; children as cultural mediators; and how the public space of this multicultural neighbourhood is seen by different actors. The research data reveal that there are different forms of integration and a variety of social structures among migrants from Vietnam in Bratislava. Although the Vietnamese are widely accepted by other residents of Bratislava, their everyday interactions occur only within designated symbolic spaces – they are accepted if they are not too visible, speak Slovak and make no collective demands on the community.

Slovakia and migration – postsocialist ties

The countries of post-communist Central Europe are experiencing increasing cultural (and ethnic) diversity. Slovakia is a country with a significant share of indigenous minorities.1 Following accession to the European Union in 2004 the situation changed and the numbers migrating for personal or economic reasons started to grow fast.2 The total number of foreigners3 in Slovakia rose from 22 100 in 2004 to 76 000 by the end of 2014.4 However, foreigners continue to represent only a small share of Slovakia’s total population, so the current share of migrants in local populations remains limited.

Slovakia’s declared integration and migration policies focus on integration and administration at the local level.5 However, these have not, as yet, been translated into any concrete integration schemes, with individual local councils often failing to realise that the migrant population in their territory is on the increase. The growing number of migrants presents various challenges for their integration at local level. Legally, foreigners with a permanent right to stay are regarded as citizens in a given municipality,6 which entitles them to a range of services. Without a long-term integration strategy and specific mechanisms for integration, migrants can be increasingly disadvantaged over time. Either they become permanently excluded through segregation and marginalisation, or they are fully assimilated into the local culture.

It is social integration that preserves space for diversity for both migrants and the majority society (which is also not homogeneous) (Rákoczyová, Pořizková 2009). The key argument in support of further increasing local powers is that, though migration and integration policies are defined at the national level, the integration process itself occurs locally (OECD 2006; Chert, McNeil 2012; Ramalingam 2013). The social integration of an individual thus occurs as part of daily life, in a specific place or neighbourhood. Thus not only is the social dimension of integration vital, but local conditions and institutions also prove decisive in shaping the integration process.

Social integration largely takes place at the micro level: it involves ties and relationships formed by people in their daily lives. The present study focuses on the local level of integration and the perception of solidarity among people in the Bratislava neighbourhood where the qualitative research was conducted. Dimitrovka is a post-industrial residential area within the city of Bratislava. It was originally built for workers employed in a chemical plant located there. A high proportion of the Vietnamese population live in the area, making it a symbolic centre for Vietnamese people living in Bratislava.

The study7 draws on the deconstructivist approach to analysis of national and ethnic groups, which looks at integration as a society-wide process. The qualitative research made use of in-depth ethnographic interviews and participant observation in the selected location, conducted in several stages between 2010 and 2013, mostly in the autumn of 2013. These methods contributed to understanding the respondents’ way of life as they themselves saw it. The research sample consisted of twenty respondents: four representatives of the municipality (local authorities, primary schools, cultural institutions) and sixteen residents, eight of whom were of migrant background.8

Theoretical and methodological approach

Although the principal focus is the Vietnamese people in Bratislava, the research aimed to avoid using the ethnic group and ethnic community as the unit of analysis or the sole object of study. Social anthropologists Nina Glick Schiller and Ayse Çağlar, arguing against viewing migrants through an ethnic lens, point out that this approach prioritises one form of identification and subjectivity as the basis for social interaction and the source of social capital over other forms (Glick Schiller, Çağlar 2007: 16–17). In other words, research on migration and the integration of migrants often emphasises their ethnic origin, while their other social identities remain in the background. Ethnicity, race and nation are ways of perception, interpretation and representation of the social world. They are not real things in the world, but perspective of the world (Brubaker 2004: 17). In pursuit of this argument, the present study assumes a critical attitude towards ethnic groups, and is not limited to exploring the Vietnamese ethnic group as a unit of analysis or a research object. It focuses on individuals – residents in one particular neighbourhood – their social ties, relations, social networks and the social fields formed by these networks. It explores various pathways of incorporation, rather than concentrating solely on ethnic pathways. The study focuses on processes and social relations, and its orientation encourages the exploration of multilevel ties within and across the boundaries of nation-states and facilitates the discussion of simultaneity – incorporation both within a nation-state and transnationally (Glick Schiller, Çağlar, Guldbrandsen 2006: 614).

Respondents are viewed as active agents whose behaviour, interpretations and constructions are structured and constrained (Brettel, Hollifield 2000: 4). The research presented here involved observation of how they take decisions and view their social ties. By their own definition, migrants represent neither a social group in the strict sense of the term, nor a subgroup. The Slovak migration expert Boris Divinský suggests that the division of migrants into groups depends on a number of different criteria, including their motives for mobility, legal status of their stay, type of residence permit, direction of their movement, length of stay, and country of origin (Divinský, Bargerová 2008). These categories are inevitably imprecise, and the relevance of such definitional confusion is questionable. Social scientists tend to accept the concepts of group and locality as unproblematic and natural (Brubaker 2002), often going so far as to use the terminology and the implicit cultural presuppositions that form the basis of the policy of individual nation states, including immigration policy. Perhaps the general consensus is that ‘a group’ is a culturally constructed social representation, and it is important to distinguish between groups and categories, and how people and organisations do things with categories (Brubaker, 2004: 13). Even more importantly, migrants do not usually give themselves legal or political labels (Tužinská 2009). Nevertheless, these labels are widely used in texts on migration. Understandably, like anybody else, migrants perceive themselves primarily as members of their own social networks.

Migration from Vietnam

To provide a context for the situation of the Vietnamese in Slovakia I will briefly review Slovakia’s history as a migration destination, and the history of Vietnamese migration to Slovakia. During the communist era labour migration in Slovakia (Czechoslovakia) was regulated by a network of intergovernmental agreements and business contracts. Vietnamese people began arriving in Czechoslovakia from the 1950s onwards on the basis of an agreement on mutual economic support and ‘socialist cooperation’ between Czechoslovakia and Vietnam (Williams, Baláž 2005). Under the agreement, Czechoslovakia trained Vietnamese students and workers in mechanical engineering and manufacturing industry. Immigration peaked in the 1980s when 30 000 Vietnamese workers were resident in the Czech Socialist Republic and 6 500 – in the Slovak Socialist Republic.9

The year 1989 marked a turning point in Vietnamese migration to Czechoslovakia, when the originally state-organised migration began to be replaced by spontaneous economic migration. Migration from Vietnam continued through relatively well-established social networks or ‘migratory chains.’ Once the Vietnamese moved to Slovakia, individuals usually preserved and maintained their transnational networks and links to Vietnam which played an important role in encouraging further migration based on the existing social networks.

At the beginning of the 1990s Czechoslovakia renounced the agreements with Vietnam. After the fall of the communist regime and the consequent de-industrialisation of Slovakia, the Vietnamese were among the first to lose their jobs in state-owned companies, and alternative employment possibilities were limited. At the same time it was very difficult to obtain work permits, so they were faced with attempts to repatriate them. Many left Slovakia either to move further west or to return to Vietnam.

The year 1989 saw the beginning of the restoration of a capitalist economy. In the 1990s a number of Vietnamese started to run retail businesses as it was one of the few ways they could remain legally in Slovakia. Trading licences enabled them to obtain temporary residence permits for the purpose of conducting business. They were also eager to grasp new opportunities to succeed in a new field of endeavour. After the fall of communism, there was a general lack of business experience and access to suppliers and wholesale networks among the population as a whole, yet migrants managed to respond to local opportunities, competing successfully with the native population. Both the majority population and the Vietnamese were subject to the same starting conditions, but knowledge, education and economic status differed between individuals. It is the first generation of migrants that tends to be especially strongly motivated to achieve economic success, which explains the higher share of entrepreneurs among them. The transnational networks of migrants still present in the country were helpful in the launch of businesses. The type of business that would prove successful was determined by the economic situation of the local population (Glick Schiller et al. 2006: 617). The consumer behaviour of Slovak citizens was influenced by their limited access to goods (Lutherová 2013: 49–50).

The highest concentration of migrants in Slovakia can be found in Bratislava because the city offers the widest range of jobs. Although there are no exclusively ethnic districts in Bratislava, there are certain areas where the Vietnamese tend to settle. In 2013, there were 2 069 Vietnamese nationals in Slovakia whose status was ‘foreigner,’ either permanently or temporarily residents.10 Of these, 27 per cent (566) live in Bratislava, the majority of them (469) in the Third District (Nové Mesto, Rača, Vajnory).11 Bratislava also boasts the biggest open-air market in the country, Miletička, and other smaller markets, such as Jedlíková, or bigger wholesale stores at Stará Vajnorská Street. Most of the active civic associations for Vietnamese people in Slovakia are headquartered in Bratislava, including the Vietnamese Community in Slovakia,12 the Slovak-Vietnamese Chamber of Commerce13 and the Union of Vietnamese Women in Slovakia. Since July 2011, the Vietnamese Embassy has also been located in Bratislava.

Dimitrovka – the chimney neighourhood

The city part of Bratislava – Bratislava-Nové Mesto is among the most ethnically diverse areas in Slovakia. According to data supplied by the Border and Aliens Police, people from 96 different countries lived in the district in 2012. The total number of foreigners was 2 837 (469 of whom were Vietnamese), which is 7.73 per cent of the total population. The data do not include the naturalised migrant population, that is, individuals who have obtained citizenship. The lack of statistical data on (second-generation) naturalised migrants makes it difficult to estimate their proportion within the overall population both at local level and nationwide. However, it is likely that the migrant population in the Dimitrovka area is even higher.

This study focuses on Dimitrovka because of its ethnically diverse population. Dimitrovka is an area in Bratislava-Nové Mesto. Its inhabitants are referred to as Novomešťania (Newtowners) or Dimitrovčania (inhabitants of the Dimitrovka neighbourhood). It was originally built for workers in the Dynamit Nobel Chemical Plant, later renamed the Yuri Dimitrov Chemical Plant (and renamed Istrochem in 1991). During the communist era heavy industry was strongly supported and systematically buttressed by the state (Lutherová 2013: 9), and the construction of housing in Dimitrovka for workers and staff at the chemical plant is a result of this policy. Dimitrovka used to be on the edge of the city, though this is no longer the case due to urban expansion.

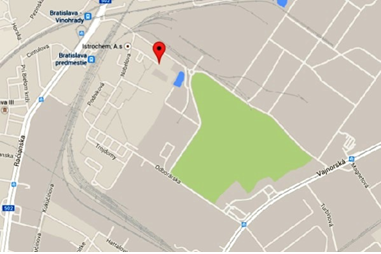

The residents of Dimitrovka used to refer to the neighbourhood as a ‘village’ or ‘community’ where everyone knew everyone else. Even today Dimitrovka is somewhat separated from the rest of the district, located between two major arterial roads leading to exit routes from the city. On one side a railway line divides it from the Vinohrady quarter and a street (Odborárska) and the former plant are boundaries on the other. It is the physical distances that make Dimitrovka appear to be a specific delineated area within Bratislava-Nové Mesto (see Illustration 1).

Illustration 1. Map of Dimitrovka

Source: Google Maps.

In the 1980s the Vietnamese started arriving in Dimitrovka as workers in the plant. The infrastructure built for the plant workers included a swimming pool, a park, shops, services and a school. Vietnamese people shared the neighbourhood with other workers housed in a dormitory near the plant. Dimitrovka can thus be termed a ‘working-class city district.’ After production ceased in the 1990s, most Vietnamese returned to their home country or migrated further west. Some decided to settle in Bratislava, and a number of them remained in the dormitory. Today about 150 people live here – new migrants and former factory employees. A few years ago the dormitory building was first rented and later purchased by a Vietnamese businessman (Gašparovská 2006: 15). It was refurbished as a residential and non-residential complex and now represents the centre of social and business life for the Vietnamese in Bratislava. A number of businessmen from Vietnam have their warehouses here. Some residents are employed elsewhere; others tend to be small traders who have their own retail businesses, such as small clothing shops, fruit and vegetable stores, nail studios and restaurants/bistros in Bratislava. This group were professionals or students in Slovakia before 1989, whose relatives joined them later through social networks. As a result, some multi-member families live in the former dormitory complex. Their reasons for staying there vary. A number of families and individuals prefer the idea of ‘shared’ housing to owning their own accommodation. Some individuals and later their families have been living here since their arrival in Slovakia ten or more years ago. One such resident is Kim: We knew the Vietnamese live here; that it is the accommodation and the owner would give us good deal for the rent… We live here as tenants…

The area surrounding the former dormitory contains a Vietnamese restaurant, grocery store, karaoke bar, hair salon, telephone booth, travel agency, storage depot, clothing shop and nail studio. The building’s owner also provides a satellite connection, giving access to a number of Vietnamese television channels.

Some of the Vietnamese families have bought or rented properties in the nearby block of flats. Some of the residents expressed their anxiety about the density of the Vietnamese community living in the neighbourhood. Ondrej, who has been living and working in Dimitrovka for five years, expressed his distrust in connection to the Vietnamese living in the area: It seems that maybe in future – in ten or fifteen years – Dimitrovka will be Vietnamese neighbourhood.

In the next section, therefore, I take a closer look at residents’ perception of the diversity in their locality.

The limits of integration

The social setting has a powerful effect on the ways in which an apparent minority and its individual members see themselves and identify with the country of settlement. In other words, there are no ethnic minorities without an ethnic majority (Fenton 2003: 165). The pattern of public and political discourse about ‘integration’ is based on the presumption that as long as migrants try hard enough, are kind and speak Slovak, do not draw attention to their problems, do not abuse the social security system and work hard, they deserve to be accepted in ‘our’ society. This neo-assimilationist discourse in Slovak (and/or European) society is based on a strong territorial and national identity that is in stark contrast with the fluid, pluralistic and transnational society of the twenty-first century (Roca iCapara 2011). Integration is the responsibility not just of migrants, but of society as a whole. The state and institutions in the country of settlement, as well as public attitudes towards migrants, play an important role. Previous research into attitudes to migration has offered a somewhat negative picture of Slovakia as a country of restrictive, non-inclusive policies, with a hostile and even xenophobic view of migrants, and a society too conservative and intolerant of otherness. A study entitled Public Attitudes to Migrants and International Migration in SR carried out in 2009 by the International Organisation for Migration suggests that a significant proportion of Slovakia’s population is not prepared to welcome foreigners and has a problem accepting otherness and perceiving diversity in Slovakia as a natural phenomenon (Vašečka 2009: 33). Attitudes to migrants and to diversity in general are influenced by public discourse, and by the contributions of individual groups to community life and their visibility in the public space. Despite the relatively high number of migrants in the neighbourhood, ethnic and linguistic diversity are not seen as something common or ‘normal.’ The population in the neighbourhood, though used to the greater number of Vietnamese people in Bratislava-Nové Mesto, maintains a largely cautious and reserved attitude towards them.

Even though the presence of national minorities makes Slovakia ethnically quite diverse, the population has not, as yet, had enough experience of cultural or ethnic diversity. Although the free movement of people outside the territory of Slovakia began after the political changes of 1989, it was not until Slovakia’s entry to the European Union in 2004 that it got underway in earnest. The ability to perceive other languages and people from other cultures as part of daily life is only now beginning to emerge in Slovakia. As my research shows, people accept foreign languages when it comes to making declarations, and yet within a specific context they consider them to be strange and outside the framework of public space.

The Vietnamese I interviewed often used the phrase ‘if we behave properly’ to illustrate the sometimes deliberate fulfilment of the majority society’s expectations and/or the type of conduct in public contexts that others expect and consider appropriate. Chung, the young Vietnamese woman explained to me:

Under normal circumstances, if I was home in Vietnam, I would allow myself to get upset, to say what I think, but I realise that they look at me with different eyes, so I try to control myself, simply to express myself neutrally. I thus got into a state that I no longer appear as a person, but people notice very much that I am a foreigner, that my features are Vietnamese, that – she is – the Vietnamese are like that.

Hanh has been living in Dimitrovka since 1990s. She described her feeling to Vietnam where she feels at home in a known environment: if people treat us normally, politely. I miss home, Vietnam a lot, the friendly relations, the sense of belonging. Ngon links home to language and tolerance, an understanding of everyday context and non-verbal communication:

When I am in Vietnam, I am in my home environment, I hear the sounds, I know what people say, and I understand a hundred percent… I thus feel more secure in that social context. Here in Slovakia I still feel a bit out of place, I cannot join the society fully… I sometimes feel like someone on the margins, by not hearing my mother tongue in the social context, on the street, I do not know who thinks what…

In this context the respondents referred to Vietnam as something familiar, known not only linguistically but also in terms of cultural and human context. Even though they consider Bratislava to be their second home, they reflect on their inferior position in a society that does not deem them equal citizens.

Diversified city

Integration is manifest in the nature, quality and quantity of social contacts with members of the majority society. These may vary from very close, informal and intimate relationships (strong ties) to formal and institutionalised ties (membership of voluntary groups, clubs, faith communities, etc.) (Rákoczyová, Pořízková 2009: 32).

The neighbourhood under study is highly diversified, not just in terms of ethnicity but also in age and social status. Both older settlers and new young families live there. It is the older population in particular who have appropriated the area and identify more closely with it. New arrivals come to live here because of the lower property prices and the quieter family-friendly environment. It is members of the older generation who describe the area through stories connected with the plant and the times when the residential area was a busy workplace. They invoke a remembered affective geography which grounds strong and sometimes exclusionary forms of place-based belonging (Gidley 2013: 364). During one of the interviews Ondrej remembered how he settled in Dimitrovka and was recognised as a stranger in the area:

This, the street is actually a small village where everyone knows everyone, we all know each other. When I first came here, they looked at me wondering who I was, what I was. Over the years the relationship is the one when we know every dog and every cat here…

The Vietnamese in Bratislava represent a relatively coherent group with strongly bonded social capital that guarantees them support and assistance. Relationships with the majority population, and the consequent acquisition of bridging social capital, develop in quite an individual way. Again, it is the attitude both of the majority population and of society as a whole towards migrants that plays a decisive role here. If attitudes are negative over a long period of time, it may lead to migrants isolating themselves within ethnically defined social networks. The Vietnamese I spoke with had developed ties at different levels. Most relationships and communication had come about through their children: at the playground, at school, in interest groups or during cultural activities for children. Relations between Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese inhabitants of the neighbourhood lead to a distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them.’ One respondent’s statement showed that the way people think about Vietnamese children is to contrast them to the ‘white’ children who are in the ‘normal’ category. The use of the term ‘normal’ demonstrates what the residents perceive as the norm (white children) and deviation from the norm (Vietnamese children). Such thinking also reflects that to some degree, acceptance or non-acceptance of the Vietnamese as ‘normal’ and ‘ours,’ as members of the wider group of residents in the neighbourhood, is being negotiated. Zuzana:

I like these kids, for instance. They’re no… well, but there are no doubt some outcasts, but we have plenty of such white kids here in the living quarters, the normal ones, well, normal – white, who are worse than the Vietnamese. The way they are make me prefer a Vietnamese, if I were to babysit a boy. I think they are polite, tidy, though there are no doubt exceptions among them as well – just like everywhere else.

The Vietnamese who live in this area generally show a preference for their close relatives and friends. Whilst at the public level we can observe and perceive the neighbourhood as multicultural, multiculturalism is commonly linked to private segregation. This, in turn, sustains the anonymity of lives behind the closed doors (Gidley 2013). Even though Vietnamese people have been resident in the neighbourhood for a number of years, the local population still does not consider them to be original settlers, to be ‘ours.’ Whilst the majority watch the Vietnamese from a distance, taking note of their activities (business or cultural) in the area, contact goes no further than this. Their coexistence can be characterised thus: ‘they know of each other, but do not know each other.’ Nevertheless, the migrants can also be seen to be maintaining a certain distance, particularly the Vietnamese who create quite a compact and cohesive community in the area. The residential block which is the centre of community life is surrounded by a fence. The fenced area contains a children’s playground and an outdoor seating area, creating something of a physical entry barrier for other residents.

Stronger ties between migrants and other residents are largely prevented by the enduring language barrier. The relationships between majority population and migrants are (at least among adults) thus kept within certain limits in the neighbourhood, with mutual tolerance, but an absence of closer ties. As Ngon illustrates on his experience: When I wanted to express something, my lack of fluency in Slovak made the communication a problem.

One specific type of relationship between the residents and the Vietnamese is looking after small children. Nannies known as ‘grannies’ or ‘aunties’ look after children up to the age of three who are too young for kindergarten. Sometimes nannies also take older children to school. The nannies are either Slovak women (particularly pensioners) or mothers on maternity leave. This enables others, largely Vietnamese women, to return to work very soon after childbirth, supplementing their maternity and child benefit income. Nannies usually obtain work by

The residents of Dimitrovka know each other by sight. These acquaintances sometimes develop into further contact and communication. Families living in adjacent flats, for example, may overcome the limitations of anonymity by improving their relationship. Ondrej differentiates between his neighbours and other Vietnamese residents:

For instance, there is a Vietnamese man who lives on our staircase. He gave me the keys of his flat for a month as he went to Vietnam with his wife and children… But the other Vietnamese… we just say hi to each other and leave it at that.

Another type of relationship between the Vietnamese and other residents is the provision of services. Residents and people who work in the area eat at a restaurant in the residential area or shop at the Asian grocery store (part of the restaurant) which offers mainly Vietnamese products. There is no sign outside the restaurant to identify it, so people have heard about it largely through their own social networks.

(In)visibility: city and migrants

The cultural diversity of Dimitrovka is not apparent to anyone passing through the area. The same applies to the presence of migrants in other aspects of the public space, for instance architecture or public symbols of religion, such as a Buddhist Temple.

Despite the relatively high number of migrant residents, the authorities – as represented by district councillors – do not reflect or respect the diversity of the local population, nor do they address local integration strategies. These elected representatives do not see the migrants as active agents; planning, whether symbolic, political, social or economic, does not take account of diversity. The Bratislava-Nové Mesto local council has announced plans to support different categories of residents through various events and activities, such as the construction of centres for the elderly, support for young families, rebuilding or refurbishing primary schools, kindergartens and children’s playgrounds. At the same time it actively involves residents in the running of their city part through open discussion forums and voluntary activities. In this respect strong civic activism is the source of numerous initiatives addressed to the city council.

The identity of the Newtowners (Novomešťania) is also preserved through the local magazine The New Town Voice. Residents’ Magazine of the district of Bratislava-Nové Mesto [Hlas Nového Mesta. Časopis obyvateľov mestskej časti Bratislava-Nové Mesto]. This provides information on local activities and representatives, and on the history of the district and cultural events. Its contribution to the discourse, however, addresses local migrants only marginally. The Vietnamese, quite a large group within the local area, are altogether unrepresented in this local periodical. There is thus no symbolic representation of diversity and migrants in the public space. Representation of Vietnamese people in local media (for instance in photographs of city life) would contribute to recognition of their presence and of themselves as members of the local community.

The policy and planning documents of the local authorities should define the inclusive nature of the city for all residents. A number of municipalities define migrants and minorities through their otherness and differences¸ instead of highlighting their basic needs and their status of belonging to the municipality as equal residents. In this way they exclude migrants from the jigsaw of ‘common residents’ (Ferenčuhová 2006: 150). Whatever applies at national level is reflected at local level. The cultivation of identity is also part of the institutional strategy of an integrated society, as it raises awareness among different groups that they belong to a given community, and also helps them identify emotionally with that community (Szaló 2003: 38).

In this respect the Vietnamese have not, as yet, attempted to participate in the administration of public affairs. Their civic groups (such as the Vietnamese Community of Slovakia and the Union of Vietnamese Women) organise festivals throughout the year in the local cultural centre (New Year, Children’s Day, Women’s Day, etc.). However, these events are not open to the general public, but only to the Vietnamese community. The city does not arrange any multicultural activities that would represent the local migrants. The few public events have included a performance by a Vietnamese puppet theatre in 2012 on Lake Kuchajda and sports activities, such as ‘a football match against racism.’

Civil society is only just emerging in Slovakia. The post-1989 transformation and the subsequent social changes have affected people of all social levels to varying degrees, and everyone has had to adapt to new conditions. They have also affected Vietnamese migrants who arrived in Slovakia under communism and experienced the transition from a totalitarian regime to democracy. Activism and the desire to participate in the running of society are only just beginning to develop, as active, engaged citizens become aware of the need to get involved in civil society. The Vietnamese are no different in this respect. Most of those who live in Bratislava-Nové Mesto do not participate in public affairs and are not active at local level, although leaders of civic groups are involved in a limited range of activities. Not only do the Vietnamese not feel they belong among the local residents, but because they often do not know their rights and entitlements, they do not approach the local authority for help. The authorities thus gain the impression that the migrants do not need anything and so local policies do not need to be altered. The roots of the problem lie in the limited awareness and the lack of public information accessible to all local residents including migrants.

One of the few activities organised by the representatives of the Vietnamese community in Bratislava-Nové Mesto was a Vietnamese language course at the local primary school. It received broad media coverage and was presented by the media as an example of cooperation between the local council and the Vietnamese in Bratislava. In addition to its practical aspect, a course such as this offers important added value as a symbol of integration that recognises, supports and seeks to maintain equally valuable but different cultural identities. Yet in Slovakia the opposite tendency is more frequently observed: migrants are expected to give up most of their cultural distinctiveness and accept Slovak identity, much as though multiple identities were not allowed. For instance, when migrants dressed in Slovakian folk costumes sing Slovakian folk songs, they are very well received. This could also be seen as a manifestation of loyalty to the host country. The cultural identity of migrants, particularly that of the Vietnamese community, is essentially seen as inherently their own; they ought to subscribe to and present it. Yet not every migrant experiences cultural identity in this way, and they do not all wish to manifest it externally, outside their community. Local schools try to actively engage the Vietnamese community in cultural activities, but are often rebuffed:

I told them recently: I do more for you than you do yourselves. Why don’t you want? Last year we celebrated the 120th anniversary of our school. I had to press them so much! So they did one number which entailed so much work for me to even bring them in (representative of the local council).

The school representatives negotiate about the fact of cultural diversity within the school life without any previous experience. They are not sure how to deal with such a diverse community and do not have any methodologies and guidelines developed for multicultural school environment.

Conclusion

The study presented here aimed to analyse the social integration of migrants in cities, particularly as regards the social and cultural diversity of a district in Bratislava. The Vietnamese people living there are relatively well received by the population at local level. Yet they only operate within a symbolic space that has been assigned to them for informal day-to-day interactions: they are accepted if they speak Slovak and make no collective demands. In telling the story of their lives on the estate, many residents show an understanding of place and invoke a remembered affective geography which grounds strong and sometimes exclusionary forms of place-based belonging.

I approached migrants as residents of the city and actors within and across space rather than as an aggregated Vietnamese ‘community.’ I focused on local-level dynamics and processes of belonging – the very local level is important for understanding questions of belonging and expressions of diversity.

The areas examined did not reveal links between residents and migrants, who tend to live separate lives next door to each other, even though they take notice of and respect each other up to a point. Yet neither crosses the notional limits. This is because migrants are not perceived as part of the wider local community; they are not deemed to be ‘ours.’ On the migrants’ part, their non-acceptance is manifested, for instance, in their limited (and/or non-existent) civic and political participation. The research has shown that hitherto migrants have accepted this situation. Nevertheless, until they feel part of the wider political community, they cannot significantly contribute to its development (and not merely in economic terms). Despite their respect for the established ‘rules,’ migrants often develop a sense that the majority society does not accept them completely. Yet mutual acceptance by both parties is an important prerequisite for integration.

City-level policies do not yet include an inclusive city strategy, or policies seeking to better meet the needs of migrant residents and their engagement with wider society. The future image of the neighbourhood and the place of migrants within it will depend on the authorities’ responses to the challenges of diversity.

Notes

1 According to the National Census minorities such as Hungarians, Czechs, Roma and Ruthenians account for about 19.3 per cent of total population in Slovakia, e.g. (Základné údaje zo Sčítania obyvateľov, domov a bytov 2011 (2012).

2 For more on migration and integration in Slovakia after EU accession in 2004, see Bargerová Gallová Kriglerová, Gažovičová, Kadlečíková (2012); Gažovičová (2011); Divinský (2009).

3 ‘Foreigners’ is a legal term that includes immigrants with permanent, temporary or tolerated legal stay in the Slovak Republic. This number does not include migrants with Slovak citizenship.

4 In 2014, there were 76 715 foreigners with residence permits in Slovakia – of these 29 171 were from third countries and 47 544 were EU citizens. Source: Statistical Overview of Legal and Irregular Migration in the Slovak Republic in 2014. Police Corps Presidium, Bureau of Border and Aliens Police.

5 The main documentary sources on national migration (and integration) policy are: Migration Policy of the Slovak Republic with a Perspective until 2020, Integration Policy of the Slovak Republic, (prior to it Concept of Foreigner Integration in the Slovak Republic).

6 Foreigners with the status of permanent stay in the Slovak Republic have active and passive voting rights, but only in relation to the local municipalities and regional districts. According to the law foreigners in Slovakia cannot vote and cannot be elected to the national parliament.

7 The text is one of the outcomes of the research project Family Histories. Intergenerational Transfer of Representation of Political and Social Changes, Projekt VEGA 2/0086/14, Institute of Ethnology, Slovak Academy of Sciences. The research was also partly conducted with my colleagues Elena Gallová Kriglerová, Alena Chudžíková and Martina Sukulová as part of the research project Migrants in Cities: Present and (In)Visible, European Fund for Integration of Third Country Nationals, Institute for Public Affairs, CVEK, 2014. For more see the published book: Hlinčíková, Chudžíková, Kriglerová, Sekulová (2014).

8 All the names of informants mentioned in the text are fictitious – the real names of my informants are not used in the paper.

9 Online on: http://migraceonline.cz/e-knihovna/?x=2274071#_ftn1.

10 Source: Statistical Overview of Legal and Irregular Migration in the Slovak Republic. 1st half of 2013. Police Corps Presidium, Bureau of Border and Aliens Police.

11 Statistics of the Bureau of Border and Aliens Police.

12 http://www.congdongvietnam.eu/index-sk.php?part=tinnhanh&article=90.

References

Bargerová Z., Gallová Kriglerová E., Gažovičová T., Kadlečíková J. (2012). Integrácia migrantov na lokálnej úrovni 2. Bratislava: Centrum pre výskum etnicity a kultúry.

Brettel C., Hollifield J. F. (eds) (2000). Migration Theory: Talking Across Disciplines. New York, London: Routledge.

Brubaker R. (2002). Ethnicity without Groups. Archives Européennes de Sociologie 43(2): 163–189.

Brubaker R. (2004). Ethnicity without Groups. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: Harvard University Press.

Chert M., McNeil C. (2012). Rethinking Integration. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Divinský B. (2009). Migračné trendy v Slovenskej republike po vstupe krajiny do EÚ (2004–2008). Bratislava: International Organisation for Migration.

Divinský B., Bargerová Z. (2008). Integrácia migrantov v Slovenskej republike. Výzvy a odporúčania pre tvorcov politík. Bratislava: IOM.

Fenton S. (2003). Ethnicity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Ferenčuhová S. (2006). ‘Spolu a spokojne.’ Obrazy integrovanej spoločnosti v mestskom plánovaní. Sociální studia 2: 133–152.

Gašparovská H. (2006). Slovenskí Vietnamci, in: K. Šoltésová (ed.), Kultúra ako emócia. Multikultúrna zbierka esejí nielen o „nás“, pp. 15–24. Bratislava: Nadácia Milana Šimečku.

Gažovičová T. (2011). Vzdelávanie detí cudzincov na Slovensku. Príklady dobre praxe. Bratislava: Centrum pre výskum etnicity a kultúry a Nadácia Milana Šimečku.

Gidley B. (2013). Landscapes of Belonging, Portraits of Life: Researching Everyday Multiculture in an Inner City Estate. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 4(29): 361–376.

Glick Schiller N., Çağlar, A. (2007). Migrant Incorporation and City Scale:Towards a Theory of Locality in Migration Studies. Willy Brandt Series of Working Papers in International Migration and Ethnic Relations 2/07.

Glick Schiller N., Cağlar A., Guldbrandsen T. C. (2006). Beyond the Ethnic Lens: Locality, Globality, and Born-Again Incorporation. American Ethnologist 4(33): 612–633.

Hlinčíková M., Chudžíková A., Gallová Kriglerová E., Sekulová M. (2014). Migranti v meste: prítomní a (ne)viditeľní. Bratislava: Inštitút pre verejné otázky, CVEK.

Lutherová G. S. (2013). Premena mikro- a makrosvetov v období postsocializmu, in: A. Bitušíková, D. Luther (eds), Kultúrna a sociálna diverzita na Slovensku IV. Spoločenská zmena a adaptácia, Banská Bystrica: Ústav vedy a výskumu Univerzity Mateja Bela.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2006). From Immigration to Integration. Local Solutions to a Global Challenge. OECD. Online: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/publications/2006/green_2006_from_... (accessed: 23 March 2015).

Rákoczyová M., Pořízková H. (2009). Sociální integrace přistěhovalců – teoretická východiska výzkumu, in: M. Rákoczyová, R. Trbola (eds), Sociální integrace přistěhovalců v České republice, pp. 23–34. Praha: Slon.

Ramalingam V. (2013). Integration: What Works? Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

Roca iCapara N. (2011). Young Adults of Latin American Origin in London and Oxford: Identities, Discrimination and Social Inclusion. Working Paper No. 93. Oxford: University of Oxford, COMPAS.

Szaló C. (2003). Sociální inkluze a předpoklad kulturní zakotvenosti politické identity občanství. Sociální studia 9: 35–50.

Tužinská H. (2009). Limity integrácie migrantov na Slovensku, in: Bitušíková A., Luther D. (eds), Kultúrna a sociálna diverzita na Slovensku II. Cudzinci medzi nami, pp. 44–63. Banská Bystrica: Ústav vedy a výskumu Univerzity Mateja Bela.

Vašečka M. (2009). Postoje verejnosti k cudzincom a zahraničnej migrácii v Slovenskej republike. Bratislava: International Organisation for Migration.

Wiliams A. M., Baláž V. (2005). Vietnamese Community in Slovakia. Sociológia 37 (3): 249–274.

Základné údaje zo Sčítania obyvateľov, domov a bytov 2011. Obyvateľstvo podľa národnosti. Bratislava: Štatistický úrad SR 2012.