The (Un)Changing Language and Sentiment Associated with the Moral Panic Button (MPB) in the Wake of the Russian–Ukrainian War: The Hungarian Case

-

Author(s):Varga, TamásRakovics, ZsófiaSik, EndrePublished in:Central and Eastern European Migration Review, Vol. , No. online first, 2025, pp. 1-20DOI: 10.54667/ceemr.2025.25Received:

28 June 2024

Accepted:28 April 2025

Published:31 October 2025

Views: 63

In Hungary, several studies have analysed how migration was framed following the events of 2015. In this paper, given the distinct characteristics of the Ukrainian refugee crisis, we investigate whether the Moral Panic Button (MPB) altered its language when referring to individuals arriving from Ukraine, compared to those from elsewhere. Content-wise, we raised 2 questions: Is it true that, after the outbreak of the war, in the framing of pro-government media, the refugee label once again became the majority term instead of the unofficial migrant, in contrast to the non-MPB-operated non-government media? Is it true that this shift was somewhat limited due to the continued presence in Hungary of migration waves, primarily originating from the Middle East and Africa? To address the research questions, we utilised 2 special datasets comprising articles and Facebook posts both before and after 24 February 2022. On the one hand, we analysed the occurrence of the terms ‘migrant’ and ‘refugee’ separately for articles and Facebook posts, distinguishing between non-governmental and pro-governmental outlets. Additionally, through sentiment analysis, we sought to investigate the attitudes and emotional responses associated with key terms related to the war. Our results imply that the pro-government media in Hungary adapted its labelling and emotional framing of displaced persons significantly around the outbreak of the Russian–Ukrainian war. Whereas this shift reflected a rapid and strategic language change in the short term, especially in contrast to non-government media, the long-term trend shows a gradual return to the earlier pattern.

Introduction

The Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 significantly influenced the political stance and rhetoric of the Hungarian government. On the one hand, the government welcomed displaced individuals, although the existing legislation was a major obstacle since it forbade almost any form of entry to Hungary as an asylum-seeker (Gerő, Pokornyi, Sik and Surányi 2023). Moreover, the Hungarian government had no clear approach to the war. Although most EU sanctions were accepted by the government, a communication campaign against the same measures was launched simultaneously (Annex: picture 13, in: Sik and Krekó 2025) and the statements of leading politicians and Fidesz propagandists blamed the West for the outbreak of the war. According to a contemporary media research study, this pattern had already been observable (Göncz, Lengyel and Ilonszki 2024). Thus, 2 opposing discourses were present: the first which leaned towards integration and was based on European values prevalent in non-governmental media and another government discourse emphasising national sovereignty, Christian-based cultural identity and the importance of the nation and family, in which the European Union was more or less rejected.

In this context, a recent study on media framing indicates that Hungarian media content during the period was largely shaped by government-driven narratives (Bocskor 2024). Pro-government outlets transmitted these unaltered, often through editorials or loyal experts echoing official rhetoric. Dominant themes included EU ineffectiveness, sanctions-related economic hardship, migration and sovereignty concerns and civilisational divides between East and West. The ‘Eastern opening’ policy also remained present despite the war. Non-governmental media mostly reacted to these narratives without articulating autonomous alternatives.

In this study, we first introduce the intertwined theories (the informational autocracy and the Moral Panic Button) which are the core of our treatise and give a brief overview of the framing basis of the forthcoming analysis. Second, using a special dataset that focuses on articles published before and after 24 February 2022, we identified the reactions in the pro- and non-government media regarding the war, with a special focus on labelling. We assumed that the Fidesz-operated MPB had to change its language regarding those coming from Ukraine compared to those from elsewhere, since the Ukrainian refugee crisis is unsuitable for fear-mongering. Factors contributing to this divergence include the pre-existing patterns of Ukrainian labour migration to Hungary and the cultural similarities between the 2 populations, such as shared characteristics in terms of skin colour and religion (Gerő et al. 2023: 8). Finally, we used a different dataset to analyse the (un)changing trends of the sentiments in the online media both before and after 24 February 2022. In the context of sentiment analysis, our research question focused on whether or not the war altered attitudes towards displaced individuals. We examined the issue within the entire media coverage, as well as within the pro- and non-government media, paying attention to the operation of the MPB in the case of the latter.

Informational autocracy (IA), the Moral Panic Button (MPB) and the framing basis of propaganda

According to the original concept (Guriev and Treisman 2020), informational autocracies are lookalike democracies in which professionally and continuously manipulated public opinion is a relevant element of the fear- or crisis-mongering power game. The Hungarian model of information autocracy, while emphasising governmental competence, extensively and intensively employs various ideological narratives at both domestic and international levels (Enyedi 2023; Krekó and Enyedi 2018). These narratives are strategically utilised to generate and sustain moral panics, thereby reinforcing the regime’s legitimacy.

The concept of moral panic traces its origins to Stanley Cohen (1972). Endre Sik and Márton Gerő summarised the essence of the moral panic as follows:

…during a moral panic, an event with some kind of kernel of reality is distorted and magnified by the media in such a way that the original, usually one-time event is exaggerated, treated as a general trend, and presented to the majority society in such a way that they feel that it threatens the existence of their world (Sik and Gerő 2022: 66).

The media’s simplistic, often tabloid-style explanations play a pivotal role in identifying threats and target groups, as well as in narrowing the scope of problems and potential solutions. Such reductive portrayals not only amplify the perceived magnitude of the threat but also heighten public expectations of immediate and forceful responses from authorities (Bernáth and Messing 2015: 8).

Moral panic can be initiated through 2 primary mechanisms: bottom-up or top-down processes (Lázár and Sik 2019: 15). In the bottom-up scenario, the panic originates from the grassroots level, often sparked by rumours or gossip, which then escalates local concerns into broader societal anxieties. Conversely, a top-down, elite-engineered moral panic is orchestrated by influential figures or groups within the elite, who may exploit such panics for ideological purposes or to further their material interests. In this regard, the Moral Panic Button can be seen as a special version of Cohen’s top-to-bottom, elite-engineered moral panic – or as a professional propaganda technology operated by the actual government (Sik 2016).

The MPB fuels panic using a complex and sophisticated propaganda machine which simulates seemingly life-or-death threats to the nation (i.e. continuously recreating crises by fear-mongering). It also identifies the wrongdoer(s), who can be blamed. To achieve these goals, the MPB develops a specific language to reinforce the narratives favoured by the government and intensify social polarisation. Since Sik and Krekó (2025) summarise the history and operation of the MPB in Hungary through a selection of examples, in this subsection, we focus only on its language and, especially, its technique of labelling. This analysis will shed light on how the MPB’s language functions to categorise and frame issues in ways that reinforce the government’s narrative.

To understand the labelling technology used by MPB, first, we must become familiar with the concept of framing, which is not only ‘fragmented’ but has never been unified from the outset, as Robert M. Entman (1993) asserts.

Entman himself endeavoured to offer a comprehensive definition of ‘framing’ that would reconcile the various interpretations of the term across different disciplines within the context of communication. According to him, ‘Frames highlight some bits of information about an item that is the subject of a communication, thereby elevating them in salience. The word salience itself needs to be defined: It means making a piece of information more noticeable, meaningful, or memorable to audiences’ (Entman 1993: 52). Overall, it seems to have emerged independently in at least 2 distinct fields, developed by separate researchers. For example, in sociology and related disciplines, the concept of frames traces its origins to Goffman’s (1974) seminal work Frame Analysis. In the field of artificial intelligence, the term ‘frame’ was introduced by mathematician and computer scientist Minsky (1974), who used it to describe a data structure representing a stereotyped situation. In psychology, Kahneman and Tversky (1984) argue that framing refers to the way in which the presentation of information can significantly influence decision-making. They demonstrated that people’s choices vary depending on whether a situation is framed in terms of potential gains or potential losses.

The term ‘framing’ is employed across numerous disciplines. The essential point is that ‘while the focus on – and the exact definition of – what a frame is does differ across disciplines, the fundamental characteristic of a frame as a means of structuring and organising the world around us via stable cognitive representations can be regarded as a common feature’ (Benczes and Benczes 2018: 432). Our research adopts a sociological approach to the concept of framing. The theory of framing suggests that media content is shaped by the influence of political and business elites, who control its production, whereas ordinary individuals, lacking resources, power and communication expertise, interact with it primarily as consumers. This dynamic allows elites to shape media narratives, ensuring that messages – particularly news – are presented within interpretive frames. These frames selectively emphasise certain elements of events while marginalising others, thus distorting the original context (Bajomi-Lázár 2017: 69).

This mechanism is closely linked to the media critique developed by Chomsky and Herman (2016[1988]). In their approach, framing refers to the process by which journalists, influenced by power dynamics, employ a unified framework in news communication. This involves not only the strategic positioning of news content but also the construction of a subjective interpretive framework – a distinct discursive alternative – which, over time, becomes integrated into the value systems of media consumers. This mechanism indirectly shapes consumers’ narratives about the world (Boldog 2016: 196). Government forces that influence the media play a pivotal role in shaping public opinion. This influence is amplified by the concentration of media ownership and journalists’ frequent reliance on official sources.

In the present case, the first, though (since propaganda may intentionally conceal its underlying message) often unrecognisable component of every framing effort in the media relates to terms – such as ‘immigrant’, ‘migrant’ and ‘refugee’ – which articles use to label people crossing the border (Benczes and Ságvári 2022: 415; Sik and Simonovits 2019: 22). The chosen label(s) align(s) closely with the context of their use, the environment in which they appear and the characteristics or actions associated with the group they describe.

A substantial body of literature examines media framing associated with migration, encompassing label selection and in-depth contextual analysis, with examples drawn from various countries. Numerous studies on the general framing of immigration have identified similar patterns in news coverage across different countries and media systems. Regardless of the language or country being examined, the metaphors display little variation and seem to draw from a set of metaphorical frames, such as crime or welfare chauvinism (Cisneros 2008). Harris and Gruenewald (2020) analysed the largest national newspapers in the USA from 1990 to 2013. In their study, they employed time-series trend analyses to investigate the prevalence of the various media frames used to explain the immigration–crime relationship. Their analysis revealed that immigration–crime news narratives predominantly portray immigrants as particularly prone to criminal behaviour or as contributing to rising crime rates. Over time, such framing has grown more prevalent, with increasing mischaracterisations of undocumented immigration as inherently criminal.

Bos, Lecheler, Mewafi and Vliegenthart (2016) examined the framing of immigration in the Netherlands, aiming to test Entman’s theory regarding how the variability in issue or event presentation affects opinions, attitudes and behaviours. Their study focused on 3 frames: emancipatory, multicultural and victimisation.. The findings revealed that the emancipatory frames of the stories influence attitudes toward immigrants and intercultural behavioural intentions: the multicultural frame fosters positive effects, while the victimisation frame generates negative effects, irrespective of the story’s valence. Similar trends were observed in Belgium. Van Gorp (2005) analysed 8 Belgian newspapers from 2000 to 2003 and found that people affected by displacement were depicted either as ‘victims’ or as ‘intruders’. The victim frame portrayed these groups as poor, helpless individuals who were unable to change their circumstances and were often seen as inferior and incapable. In contrast, the intruder frame depicted them as dangerous and posing a cultural and economic threat. Other studies have generally found a more negative framing of immigration, with news coverage primarily emphasising security (e.g. Islam as a threat) and economic consequences, while discussions of cultural impacts were less prevalent (Caviedes 2015; Fengler, Bastian, Brinkmann, Zappe, Tatah, Andindilile, Assefa, Chibita, Mbaine and Obonyo 2020).

The case of Hungary, where migration is frequently associated with terrorism or crime, is often used to incite fear, aligning with international trends (CRB 2018: 43). This approach is characterised by its deterministic and direct nature. In Hungarian online media, the link between ‘migrants and crime’ or ‘migrants and terror’ is rarely presented through explicit causal claims (e.g., ‘migrants cause an increase in crime’). Instead, propagandists rely on weaker logical associations, such as implying stigma through statements like: ‘If the person is a migrant, then he is a criminal/dirty/infected’ (CRB 2018: 44). Emphasising themes of terror and violence inherently heightens fear, fosters uncertainty and undermines citizens’ trust in the modern state. From a propaganda perspective, such as that of the MPB, this approach reinforces a securitisation narrative, often culminating in the assertion that only the ruling government can safeguard the populace. Another comprehensive analysis was undertaken in the context of Hungary to examine the metaphorical framing of the label ‘migrant’ in the same year (Tóth, Csatár and Majoros 2018). The finding was that the most prominent metaphors conceptualising the migration crisis in the Hungarian online press were rooted in the following source domains: flood, war, object, press/burden, animal and building.

In the research mentioned above, which specifically addresses immigration, previous content analyses have either typically employed a broad category of actors, consolidating immigrants, refugees and asylum-seekers under a single label (Van Gorp 2015) or have focused on a singular label (CRB 2018; Tóth et al. 2018). These broad categories offer limited insight into the distinctions between the various actors featured in immigration-related news because each label evokes distinct associations, rooted in the varying (often metaphorical) conceptualisations conveyed by the terms.

The terms ‘asylum-seeker’ and ‘refugee’ are official and legal terms that refer to specific categories of people. At the international level, ‘refugee’ status is defined by the 1951 Geneva Convention, which describes a refugee as an individual who, ‘owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country’ or to return to it, while the term ‘immigrant’ applies to a person who ‘establishes his or her usual residence in the territory of a Member State for a period that is or is expected to be of at least 12 months, having previously been usually resident in another Member State or a third country’ (Torkington and Ribeiro 2019: 26). According to the principle of non-refoulement, refugees cannot be deported to countries where their lives would be at risk. In contrast, asylum-seekers do not automatically enjoy this international protection; they seek recognition as refugees in order to apply for asylum (Verleyen and Beckers 2023: 730).

Research that distinguishes between migrants and refugees has defined and differentiated these groups based on factors such as agency, economic costs, length of stay and type of threat. In Canada, Lawlor and Tolley (2017) found that migrants and refugees were framed differently in the media. Their study revealed a more negative tone in the news coverage of refugees compared to migrants, with migrants being assessed more in terms of their economic contributions.

In Hungary, the term ‘migrant” is a relatively recent addition to public discourse, emerging prominently in the aftermath of 2015. Unlike the labels ‘immigrant’ and ‘refugee’, it lacks official recognition and formal definition (Benczes and Ságvári 2022: 415). From the perspective of the MPB, the most significant distinction lies in the emotional stakes: while the term ‘refugee’ elicits solidarity, compassion and a willingness to assist, the term ‘migrant’, being a foreign word for Hungarians, fails to evoke any sense of community compassion or solidarity. If we focus solely on the prevalence of the labelling (Sik and Simonovits 2019: 23), we can conclude that, in 2015, the term ‘refugee” experienced its first notable decline in usage, coinciding with a sharp rise in the prevalence of the terms ‘immigration’ and ‘immigrant’. A second decline in the use of ‘refugee’ occurred in July 2015, alongside a decrease in the use of the term ‘migration’. By 2016 and 2017, the terms ‘immigration’, ‘immigrant’ and ‘migration’ began to supplant ‘refugee’, while the term ‘migrant’ saw a significant increase in usage. By the end of the period, various forms of ‘migration’ had largely replaced ‘refugee’.

‘Migrant’ versus ‘refugee’: The ‘(un)changing’ pattern of labelling

This study examines the frequency of labels and, rather than focusing on the specific context, seeks to analyse framing in terms of emotional content, attitude and approach through the use of sentiment analysis.

To analyse the labelling trend of online media, we created a database containing articles and posts, both downloaded with the help of a social listening tool operated by SentiOne. The keywords used to identify which content to download were: ‘immigrant’, ‘migrant’, ‘refugee’, ‘asylum-seeker’ and ‘settlement permit’. The dataset included 169,516 articles and 69,755 posts from 1 January 2022 to 18 October 2023.1

The preliminary selection of the media outlets was based on ‘visibility’ (i.e., traffic rank of the site compared to all other sites): we selected those websites that ranked higher than the 1,000th place (the source was similarweb.com). The second selection criterion was a minimum number of articles: 300 in the case of non-government and 500 in the case of pro-government media.2 The advantage of this double selection process is that it produces a selection of migration-related articles with the largest potential readership. Concerning Facebook posts, we applied a similar method to that used for online media. In the examination of the most-visited Facebook pages, we defined a minimum number of followers (N=10,000).3

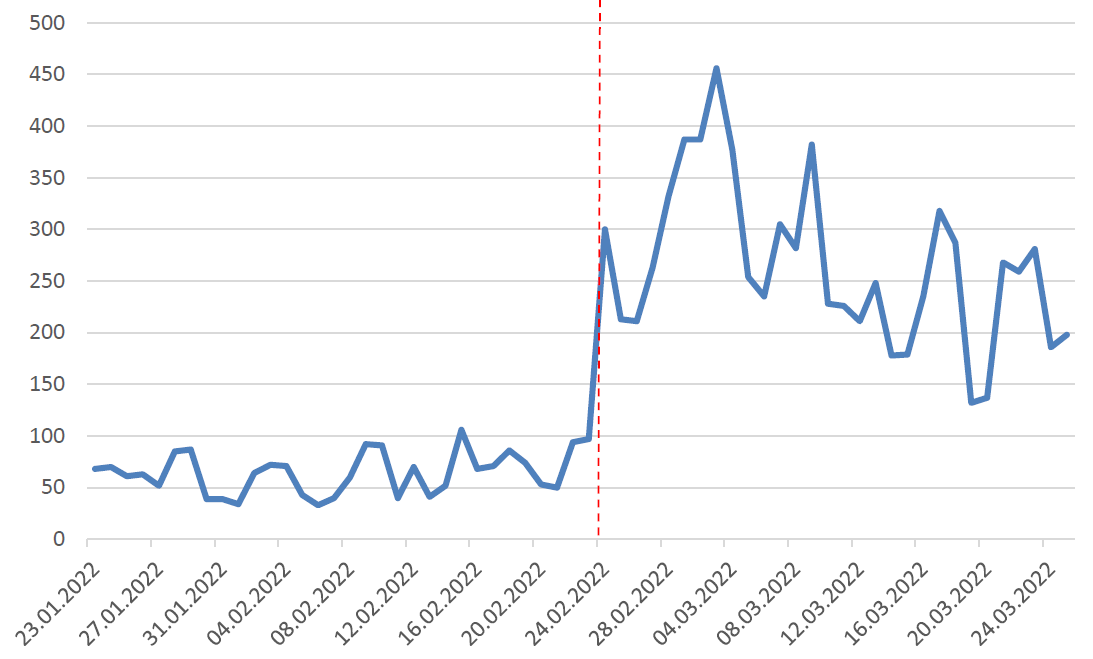

As Figure 1 shows, the war significantly increased the aggregated number of migration-related articles and posts – i.e. the latter became a ‘hot topic’ and not only temporarily.

Figure 1. The total number of the articles/posts between 23 January and 25 March 2022*

Source: Own calculation. * The vertical dashed line marks the outbreak of the war (24 February 2022).

To answer the 2 questions raised at the beginning, we first had to identify ‘MPB language’ and then operationalise it in our corpus. Accepting Rakovics and Boda’s (2025) and Surányi and Bognár’s (2025) argumentation in this special section, we used the concept of labelling as the identification of MPB-sensitive language. While the ‘menekült’ (refugee) is an official (and legal) term used to refer to specific categories of people, the word ‘migráns’ (migrant) is a newcomer in the Hungarian public discourse, with strong and negative emotional associations.

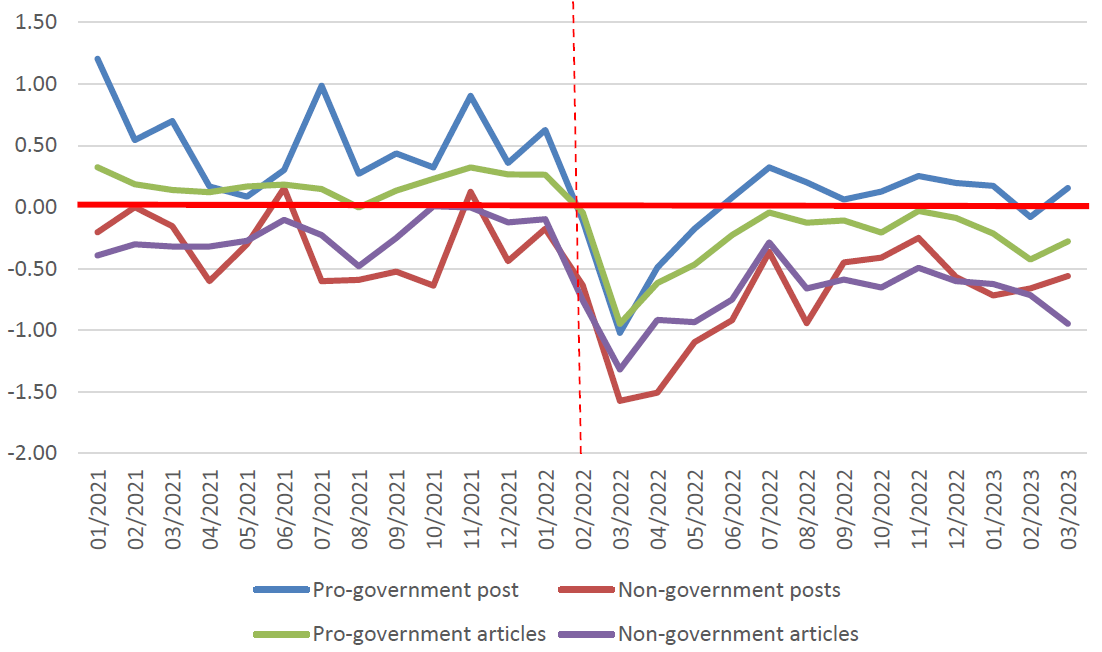

Next, we created an index that shows the proportion of uses of the term ‘migrant’, which was compared to that for the term ‘refugee’ (Figures 2 and 3). Since there were large outliers in the data, to make the figures readable we used the logarithm (10th) of the original data. If the ratio is above ‘0’, on the given day, the term ‘migrant’ was more frequently used than ‘refugee’ and, when the value is below ‘0’, the term ‘refugee’ is used more frequently. Regarding the articles (Figure 2), we found that (1) in the pre-war period, MPB-dominated pro-government media used the term ‘migrant’ more often than ‘refugee’ and (2) this was not the case with the non-government media. After the war broke out (3) the use of the term ‘migrant’ in both segments declined significantly but (4) especially in the pro-government media. Similar trends can be observed in the case of Facebook posts (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Ratio of ‘migrant’ to ‘refugee’ labels in pro- and non-government articles between 23 January and 25 March 2022*

Source: Own calculation. * The red line indicates the baseline value (when the number of the 2 labels is the same). The vertical dashed line marks the outbreak of the war (24 February 2022).

Figure 3. Ratio of ‘migrant’ to ‘refugee’ labels in pro- and non-government posts between 23 January and 25 March 2022*

Source: Own calculation. * The red line indicates the baseline value (when the number of the 2 labels is the same). The vertical dashed line marks the outbreak of the war (24 February 2022).

Figure 2 shows that, in the pro-government media, this process started approximately 3–4 days before 24 February 2022 when the Minister of National Defence was already talking about sending soldiers to the border, since ‘the soldiers must prepare for the arrival of those who have fled their homes at the borders, as well as for humanitarian tasks’.4

Extending our analysis to 26 months5 (a year before and after 24 February 2022), we calculated the ratio of the use of the terms ‘migrant’/‘refugee’ for each month (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Ratio of ‘migrant’ to ‘refugee’ labels in pro- and non-government articles and posts between January 2021 and March 2023*

Source: Own calculation. * The red line indicates the baseline value (when the number of the 2 labels is the same). The vertical dashed line marks the month of the outbreak of the war (February 2022).

Figure 4 shows that, before the outbreak of the war, the frequency of use of the term ‘migrant’ was much higher than that of ‘refugee’. This was especially the case in some periods in the pro-government media. For example, in the summer of 2021, the MPB was pressed (Annex: picture XI, in: Sik and Krekó 2025) in the form of a national consultation entitled ‘Life after the epidemic’, which again used the issue of migration, closely linked with György Soros (see Sik and Krekó 2025, the emoji in Picture 1). Three out of the 14 questions in this push poll were related to the dangers of migration (with Soros claimed to be in the background6). The small increase in the index in June and September 2021 (i.e., at the beginning and the end – with a victory campaign – of the pressing of the MPB) may be related to that national consultation.

The turning point of the index is not February and March 2022, when the frequency of use of the term ‘refugee’ reached its peak. From this point on, the word ‘refugee’ was used more frequently in the pro-government media for a year but, for a short time (March–December 2022), there was a new increase in the use of the ‘migrant’ label. This might lead to the conclusion that the MPB was still ready to use the ‘undeserving refugee’ narrative whenever needed to strengthen informational autocracy.

During the post-war period (March 2022–March 2023), the pro-government media is often characterised by articles that make almost no attempt to hide the differences inherent in labelling, i.e. talking about ‘real refugees’ as opposed to undeserving ones. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, on the official website of the Hungarian government, announced that ‘a clear distinction must be made between refugees and illegal migrants’7 and the Prime Minister made it clear in one of his regular Friday radio interviews that: ‘There are countries affected by the influx of refugees from Ukraine, such as Poland. There are also those who are affected by the influx of migrants from the south, such as Croatia, Slovenia, or Romania. However, only Hungary and, to some extent, Romania are states that are affected by both’.8

In the non-government media, over a short time period (October 2021–November 2022), the number of articles using the label ‘migrant’ was less than the number of articles that used ‘refugee’ but, like the pro-government media, there was some revival of the use of the word ‘migrant’ between March and July 2022.

Different trends can be observed on Facebook (see Figure 4): in particular, the almost complete dominance of the word ‘migrant’ on pro-government sites until February 2022. From January 2021 to February 2022, when the war broke out, there were 3 periods when significantly more posts were created that used the term ‘migrant’. This tendency deviates from the patterns observed in the media, where it can be asserted that analogous outlier periods are absent. Another notable difference is that, after the initial decline in February 2022, it seems that the dominance of the use of the label ‘migrant’ returned on Facebook and, as of July and November 2022, there were twice as many posts that used it. This trend contradicts our assumption: after the initial drop, the MPB returned to its original labelling technique on Facebook.

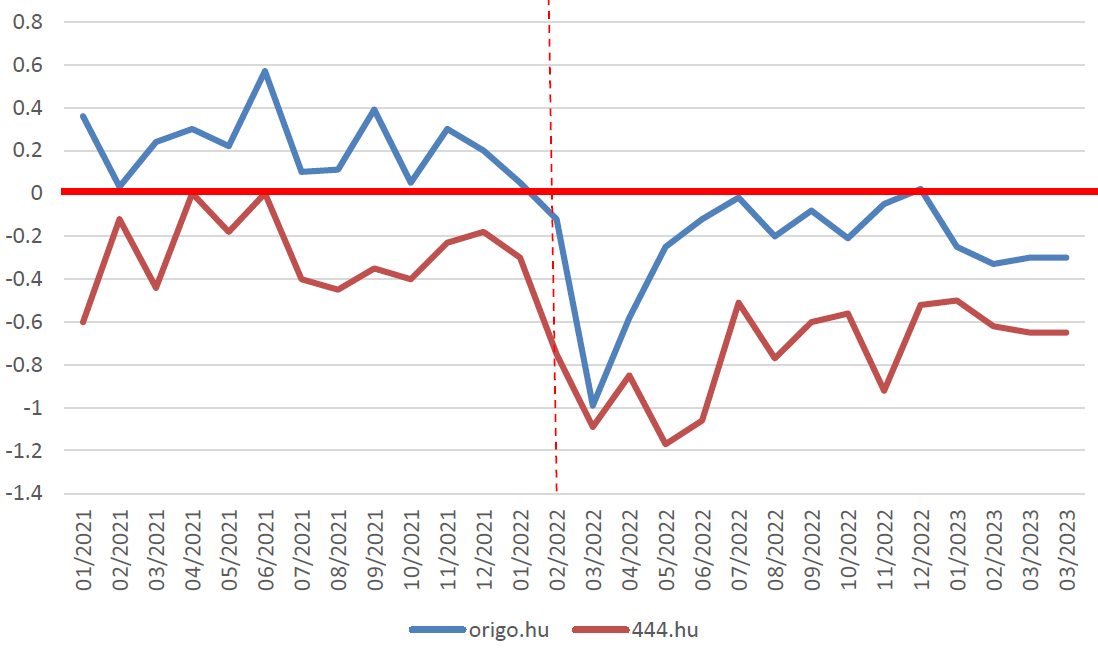

Focusing on the most ‘radical’ actors in the non-government (444.hu) and the pro-government media segments (origo.hu), a Hungarian research firm compared the labelling techniques of the two segments.9

Figure 5. Ratio of ‘migrant’ to ‘refugee’ labels in 444.hu (non-government) and origo.hu (pro-government) media sources between January 2021 and March 2023*

Source: Own calculation. * The red line indicates the baseline value (when the number of the 2 labels is the same). The vertical dashed line marks the month of the outbreak of the war (February 2022).

Comparing the results in Figure 5 to those in Figure 4, we can see that, in the pro-government radical media, the term ‘migrant’ dominated well before the outbreak of the war and the frequency of using this term started to decrease earlier (November 2021). Consistent with the trends associated with all pro-government articles, use of the term ‘migrant’ gradually started to rise again after the low point in March. Concerning the non-governmental radical media source, the term ‘refugee’ was used more frequently than in all non-governmental articles, even in the initial period.

(Un)changing sentiments?

Sentiment analysis, also known as opinion mining, is a subfield of natural language processing (NLP) that focuses on identifying and categorising opinions expressed in textual data. It emerged as a crucial tool in NLP, driven by the exponential growth of user-generated content on digital platforms (Pang and Lee 2008). It involves the systematic extraction and analysis of subjective information from texts, such as opinions, attitudes and emotions (Mohammad 2016). Sentiment analysis is a valuable tool in several domains, including business, public policy and the social sciences. It allows businesses to monitor customer sentiment, thereby facilitating improvements in product development and customer service (He, Wu, Yan, Akula and Shen 2015) and is employed by policy-makers to gauge public reaction to policies and legislation. In the social sciences, sentiment analysis is used to gain insights into public opinion on various social issues, elections and events, etc. (Mohammad 2016).

Of the 3 main approaches10 used in sentiment analysis, we opted for a lexicon-based approach that is easily interpretable and can be adjusted with domain-specific information. Lexicon-based techniques rely on pre-defined dictionaries of words annotated with sentiment scores (Taboada, Brooke, Tofiloski, Voll and Stede 2011). These approaches build on counting the occurrences of words with positive and negative sentiment in a text to determine their overall score.

For the sentiment analysis used in this research, we used the 2 corpora that were created to analyse the labelling: a ‘refugee corpus’ and a ‘migrant corpus’. In preparation for the sentiment analysis, we applied syntactic analysis11 to understand the role of each word within each sentence. We calculated the absolute and sentiment score for each sentence using the Hungarian sentiment corpus (HuSent),12 which is the sum of the sentiment values for the words in the targeted sentence. With the help of this method, we investigated the character of the discourse and how it changed over time, both in general and for selected sentences, focusing only on those containing the 2 keywords ‘migrant’ and ‘refugee’.

The text preprocessing steps were identical for both the ‘refugee corpus’ and the ‘migrant corpus’.13 As a first step, we retained only those sentences from within the specified time interval (from 1 February to 20 March 2022, encompassing 24 days before and after 24 February 2022). Subsequently, we applied a filter to ensure that the content in our corpora pertained solely to the Russian–Ukrainian war. To achieve this, we used the following keywords: ‘war’, ‘Zelensky, ‘Ukraine’, ‘Ukrainian’, ‘Ukrainians’, ‘Putin’ and ‘Russia’, ‘Russian’ and ‘Russians’. In the third step, we eliminated duplicate sentences with repeated identifiers. Finally, we selected sources used in the first part of the paper and categorised them as pro-government and non-government. After these steps, the ‘refugee database’ contained 3,021 sentences and the ‘migrant database’ contained 115 sentences.14

Besides the above-described methodology, we complemented the quantitative approach with qualitative methods. We studied the speeches sentence by sentence, focusing on the context of predefined keywords and noted all substantively relevant aspects in a bid to obtain a deeper understanding of the observed empirical patterns. We also used excerpts from the text to highlight the discursive strategies. We collected some relevant examples, showcasing the usage and interpretation of the sentiment scores, specifically in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Russian–Ukrainian war.

Examples like ‘[s]he is very concerned about the fate of refugees’ and ‘the refugees are in a very bad state’ were associated with negative sentiment scores (-3.6, respectively). Examining positive sentiment scores also contributed to the analysis: an example sentence with high positive sentiment (4) is as follows: ‘They had not yet fled the war but came to Mosonmagyaróvár in the hope of a better life’.

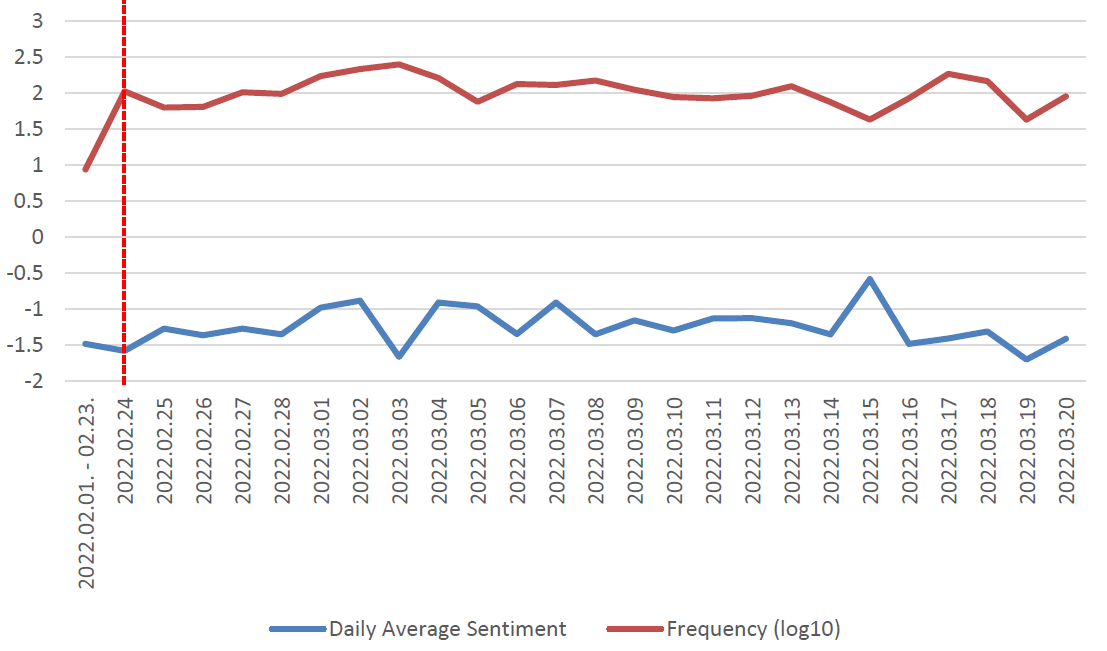

Figure 6 shows the general trend in sentiment and the frequencies of online media.15 After 24 February 2022, the frequency of war-related sentences multiplied immediately: on 23 February, there were only 11 sentences, whereas, by 24 February, the number had already increased to 106 sentences. Later, the average daily number of sentences stabilised – exhibiting minor fluctuation and maintaining this level until the end of the examined period.16

Figure 6. Daily average sentiment and frequency of sentences before and after 24 February (total corpus Nsentences=3021)*

Source: Own calculation. * The vertical dashed line marks the outbreak of the war (24 February 2022).

The sentiment scores before 24 February 2022 were often characterised by negative content, frequently featuring the word ‘war’; for example, ‘In the event of a war in Ukraine, hundreds of thousands of refugees would arrive – warned Orbán, who believes that this should be avoided but, if a war breaks out in Ukraine, Hungary has an “action plan” for this case as well’.17 February 24 did not bring as much change in the emotional charge as it did in the number of sentences. From that point onwards, the daily average sentiment stabilises around a consistent value. Like the daily average article count, several noticeable spikes are evident on our timeline.

As mentioned earlier, we examined the sentiment scores of sentences containing the word ‘refugee’ in conjunction with certain war-related terms. To do this, we defined 3 categories based on specific expressions: the first category included sentences containing the word ‘war’ as the key element of the ‘story’ while the second and third types were sentences with words referring to the main ‘actors’ (‘Zelensky’, ‘Ukraine’, ‘Ukrainian’ and their variants or the words ‘Putin’ and ‘Russia’, ‘Russian’ and their variants). We calculated the average sentiment of these terms before and after 24 February 2022 (see Table 1).18

Table 1. Average sentiment scores before and after 24 February 2022*

Source: Own calculation. * Independent samples T-tests, p<0,05. For the values in italics, due to the difference in standard deviation, we used Welch’s t-test.

All the differences between the two periods were found to be statistically significant. It can be concluded that, in the sentences that use the word ‘war’, the term ‘refugee’ was associated with the most negative tone both before and after the outbreak of the war. As for the 2 ‘actors’, the trend with sentiment change was the opposite and, in the post-escalation period, the attitude towards ‘refugee’ in the Ukrainian context was more positive than in the Russian context.

Based on Figure 7, it is apparent that the sentences containing the 3 terms show a diverse range of sentiments and oscillate a great deal.19

Figure 7. Daily evolution of sentiment scores in connection with individual concepts (War, Nsentences=747, Ukraine/Zelensky, Nsentences=2,801, Russia/Putin, Nsentences=964) before and after 24 February 2022*

Source: Own calculation. * The vertical dashed line marks the outbreak of the war (24 February 2022).

Sentences written in connection with Russia/Putin a week after the outbreak of the war, for example, tend to be more negative even than sentences containing the word ‘war’. It is noteworthy that the mention of Ukrainian/Zelensky is associated with the highest positive emotional charge during the period when the term Russia/Putin is at its lowest point.

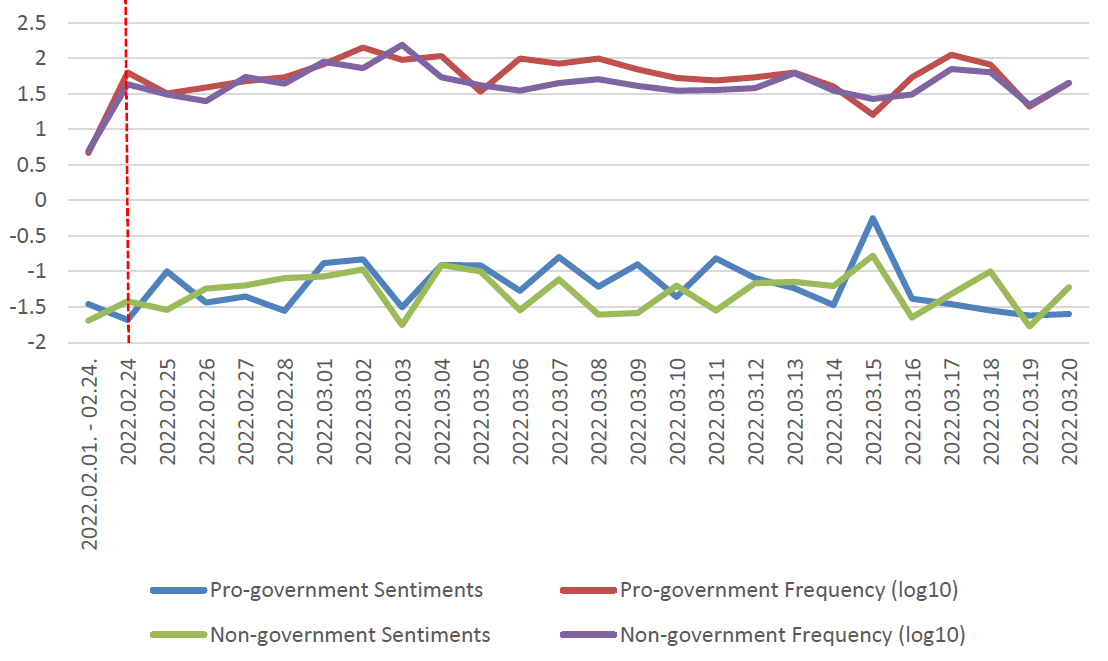

In Figure 8, we investigate the potential influence of MPB on the emotional tone of articles. The technique involved comparing the trend in the sentiment and frequency of sentences containing the term ‘refugee’ in the MPB-dominated pro-government and the less affected non-government media segments.

Figure 8. The daily average sentiment and the frequency of sentences before and after 24 February 2022 in the total pro- government corpus (Nsentences=1701) and total non-government corpus (Nsentences=1320)*

Source: Own calculation. * The vertical dashed line marks the outbreak of the war (24 February 2022).

The figure indicates that, even prior to the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the term ‘refugee’ had negative connotations within the context of the war on both sides.20 During this period, most articles focused on the influx of refugees and explored the possibility of accepting them. For example, on 21 February, there were relatively more sentences associated with distinctly negative content. At that time, Orbán met with Slovenian Prime Minister Viktor Janša in Lendava, where the following sentence was uttered and subsequently quoted by numerous sources: ‘In the 1990s, during the Yugoslav war, tens of thousands of refugees came to Hungary but, in terms of population, Ukraine is much larger than the former Yugoslavia. Therefore, if there is a problem there, the resulting refugee pressure on Hungary will have a much greater security and economic weight’.21

After Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, for a brief period the pro-government media adopted a more positive tone when writing about refugees but this trend quickly reversed. Another turning point was 5 March, when pro-government media adopted a positive stance towards refugees in their reporting for approximately a week. During this period, numerous articles featured sentences expressing refugees’ gratitude towards Hungarians, discussed donations intended for refugees or highlighted the exemplary nature of humanitarian aid efforts. The peak in positive values from the pro-government side on 15 March is attributable to several sentences discussing donations and the provision of solidarity train tickets for refugees occurring simultaneously. This form of government propaganda combines the narratives of sovereignty and solidarity. From this perspective, the Hungarian government emerges as the protagonist, facilitating assistance to Ukrainians and coordinating support, while portraying the war as an evil force that victimises Ukrainians. The government narrative emphasises that, although it cannot end the war, it provides oversight and control (rather than following prescriptions from international actors), thereby enabling Hungarians to assist those arriving from a neighbouring country.

Summary and conclusion

This study has analysed whether there was a change in the technique of labelling displaced persons arriving in Hungary around the start of the Russian–Ukrainian war. At the beginning of the study, we raised 2 questions regarding MPB-related language. The first question was more about the short-term connection between the MPB and the wave of war refugees – namely, that the pro-government media, which strongly operates the MPB, changed more in terms of ‘migrant’/‘refugee’ labelling than the non-government media.

We examined the frequency of use of the terms ‘migrant’ and ‘refugee’ separately for online media sites and Facebook posts and separately for non-government and pro-government sites. In the case of the online media, it was evident from the ratio of use of the ‘migrant’ label compared to ‘refugee’ that the MPB had to change its language towards uprooted individuals from Ukraine. Analysis of the trends on a daily basis showed how suddenly the MPB was able to react and change its labelling method.

It is also clearly visible that, before the war, the presence of the concept of ‘migrant’ was much stronger in the pro-government media and the downward trend mentioned earlier also started from a higher level. The decline reached a low approximately 2 weeks after 24 February. In sum, it can be stated that, following 17 February, when the term ‘migrant’ became more common on both sides, this change was much greater in the pro-government media.

Our second question was related to the long-term operation of the MPB. After analysing the period 1 year after the outbreak of the war, it can be stated that the use of the term ‘migrant’ in the pro-government media gradually came back into use, although its previous clear predominance was not achieved again. In addition to the wave of displaced individuals from the Russian–Ukrainian war, the MPB had to take into account other forms of migration that are not connected to it. Overall, it can be concluded that the MPB was able to change its language very quickly at the outbreak of the war but this change can only be said to be temporary in the long term.

In analysing the sentiment scores, we aimed to examine attitudes towards people fleeing the war in the Hungarian media in the context of the Russian–Ukrainian war. Our main question was whether 24 February 2022 brought about any changes in emotional content and interest. We investigated this question using a unified corpus as well as pro-government and non-government corpora separately.

Based on our analysis of media coverage across all outlets, it can be concluded that content related to the term ‘refugee’ became more negative after 24 February 2022 and the volume of content related to this term increased, particularly immediately after the outbreak of the war. However, it was also demonstrated that the emotional content of sentences about ‘refugees’ varied depending on the war-related actor with which they were associated. Our analysis revealed that, in the context of Russia, mentions of the term ‘refugee’ tended to have a more negative tone after the outbreak of the war than mentions in the context of Ukraine.

Regarding pro-government and non-government media outlets, it was observed that the negative emotional charge towards ‘refugee’ decreased in the former after 24 February 2022. Upon analysing the sentence content, we found that this shift largely originated from their emphasis on expected solidarity, the necessity of assistance and expressions of gratitude from refugees towards Hungary.

Notes

- Regarding the pre-processing of the 2 corpora (Németh, Katona and Kmetty 2020), we identified and standardised the relevant words (tokenisation) and removed the meaningless words (stop word removal). All the steps involved in the data preprocessing were performed in R. During tokenisation, the text to be analysed is broken down into units, so that the tokens represent individual words or phrases. During stemming, the word-splicing algorithm simply cuts off all suffixes and adjectives. Instead of stemming, we can also use dictionary formatting (lemmatisation). The difference between the 2 procedures lies in the fact that, during stemming, we only remove the endings of the words identified as suffixes to reduce the different forms of the same word to a common stem while, in the case of lemmatisation, we immediately get back the meaningful, dictionary form. The choice between the 2 methods is founded on the researcher’s decision based on the research question (Grimmer and Stewart 2013). For the research described in this paper, we relied on lemmatisation.

- After the removal of the multiple publications, the thresholds are proportional to the size of the 2 corpora. Regarding the categorisation of the media outlets (pro- or non-government), we relied on ownership and/or their relation to a MPB-related organisation. We used the 2 sources the most often cited in the Hungarian literature for their identification: https://21kutatokozpont.hu/mediairanytu.html and https://www.valaszonline.hu/2021/01/04/a-ner-mar-a-sajto-50-szazalekat-k....

- The number of followers based on Facebook data, January 2024.

- https://24.hu/belfold/2022/02/22/honvedseg-benko-tibor-ukrajna-oroszorszag/

- For the 24-month analysis, we relied on a 20 per cent sample from another database (articles (N=74,470) and posts (N= 26,379), published between 11 February 2019 and 11 February 2022). All pre-processing and selection processes were the same as in the newer corpus.

- The questions were:

- György Soros will attack Hungary again after the epidemic, because the Hungarians are against illegal migration. Some people think that the pressure exerted by the Soros organisations should be resisted, while others think that Hungary should give way in the migration debate. What is your opinion?

- According to Brussels bureaucrats and György Soros’ organisations, the importation of ‘immigrants’ should be accelerated in the years after the epidemic. ‘Migrants’ arriving by sea must be distributed among European countries. The Hungarian government does not support any mandatory distribution. According to the government’s position, even after the epidemic, ‘migrants’ can only be accepted on a voluntary basis and it is not possible to distribute them among the countries of the union in a mandatory manner. What is your opinion?

- Some people think that an epidemiological ‘migrant’ STOP is needed in the 2 years after the epidemic. The borders must be completely closed to ‘migrants’ because they can bring new virus mutations into Hungary. According to Brussels bureaucrats, ‘migrants’ arriving during the epidemic should not be refused admission. What is your opinion?

- Világos különbséget kell tenni a menekültek és az illegális migránsok között (kormany.hu).

- Orbán Viktor: Eljött a pillanat egy új határvadászrendszer megszervezésére (hirado.hu).

- https://21kutatokozpont.hu/mediairanytu.html.

- There are at least 3 different approaches to sentiment analysis: 1) lexicon-based, 2) machine learning-based and 3) hybrid approaches.

- For the syntactic analysis, we applied universal dependency parsing, using the udpipe package in R and the udpipe_load_model function to open the file created specifically for Hungarian; ‘hungarian-szeged-ud-2.5-191206.udpipe’.

- Further information on the Hungarian sentiment corpus (HuSent) can be found here: https://rgai.inf.u-szeged.hu/node/363. According to its description, HuSent ‘is a deeply annotated Hungarian sentiment corpus. It is composed of Hungarian opinion texts written about different types of products, published on the homepage [http://divany.hu/]. The corpus is made up of 154 opinion texts and comprises (…) approximately 17,000 sentences and 251,000 tokens’. The corpus HuSent was created by Precognox Ltd and HUN-REN—SZTE Research Group on Artificial Intelligence (RGAI).

- Except that, in the case of the ‘migrant’ corpus, we had to deselect sentences containing misleading migration-related content such as ‘The primary interest of the Visegrád Group (V4) is to curtail migration’ or ‘The support and even encouragement of illegal migration is directly associated with the proliferation of anti-Semitism’.

- Due to the low number of cases in the ‘migrant’ corpus, the detailed comparative analysis of sentiment in sentences containing the terms ‘refugee’ or ‘migrant’ was not feasible. We had to restrict ourselves to comparing the aggregated results only. Contrary to our expectation, (1) in the pre- and post-war periods, the average sentiment of sentences containing the term ‘refugee’ was more negative than that of those using the term ‘migrant’ and (2) both ‘improved’ in the aftermath of the war – the average sentiment score during the pre-war period was -1.48 (‘refugee’) and -1.05 (‘migrant’) while, in the period following the outbreak of the war, it was -1.24 (‘refugee’) and -0.75 (‘migrant’).

- Due to the low number of cases, sentiment scores and sentences were aggregated before 24 February 2022; however, there were days when discussions about refugees increased significantly, such as between 8 and 11 February, when Polish authorities warned of an impending wave of ‘refugees’.

- Due to the low number of cases before 24 February 2022, the sentiment scores were aggregated in all figures and, to enhance readability, the frequency of sentences was logarithmised (using logarithm base 10).

- https://hvg.hu/itthon/20220212_Orban_evertekelo_osszefoglalo.

- We examined the change in the average frequency of sentences as well and, unsurprisingly, found a significant increase in the number of sentences in both periods.

- The daily minimum number of sentences was 3 for the concept of War, 36 for the concepts Ukraine/Zelensky and 12 for the concepts Russia/Putin.

- Due to the smaller size of the 2 corpora, we computed averages for both sentiment scores and sentence frequencies for the period preceding 24 February 2022.

- https://kormany.hu/hirek/a-magyar-es-a-szloven-gazdasag-megerosodve-keru....

Funding

This research was funded by the project ‘BRIDGES: Assessing the Production and Impact of Migration Narratives’ (Grant Agreement No. 101004564): https://www.bridges-migration.eu/.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID IDs

Tamás Varga  https://orcid.org/0009-0002-6264-8585

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-6264-8585

Zsófia Rakovics  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9903-9348

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9903-9348

Endre Sik  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4166-1852

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4166-1852

References

Bajomi-Lázár P. (2017). Manipulál-E a Media? Médiakutató 13(4): 60–80.

Benczes I., Benczes R. (2018). From Financial Support Package via Rescue Aid to Bailout: Framing the Management of the Greek Sovereign Debt Crisis. Society and Economy 40(3): 431–445.

Benczes R., Ságvári B. (2022). Migrants Are Not Welcome. Metaphorical Framing of Fled People in Hungarian Online Media, 2015–2018. Journal of Language and Politics 21(3): 413–434.

Bernáth G., Messing V. (2015). Bedarálva. A Menekültekkel Kapcsolatos Kormányzati Kampány és a Tőle Független Megszólalás Terepei. Médiakutató 16(4): 7–17.

Bocskor Á. (2024). European Union, Geopolitics and the War in Ukraine: An Analysis of Geopolitical Discourses in Hungarian Media in 2021–2022. Corvinus Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 15(3): 133–152.

Boldog D. (2016). Konszenzusgyártás az Amerikai Liberális Demokráciában. Edward S. Herman és Noam Chomsky Az Egyetértés-Gépezet. A Tömegmédia Politikai Gazdaságtana Című Könyvéről. Médiakutató 16(3–4): 195–199.

Bos L., Lecheler S., Mewafi M., Vliegenthart R. (2016). It’s the Frame That Matters: Immigrant Integration and Media Framing Effects in the Netherlands. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 55: 97–108.

Caviedes A. (2015). An Emerging ‘European’ News Portrayal of Immigration? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41(6): 897–917.

Chomsky N., Herman E.S. (2016[1988]). Az Egyetértés-Gépezet. A Tömegmédia Politikai Gazdaságtana. Budapest: L’Harmattan.

Cisneros D.J. (2008). Contaminated Communities: The Metaphor of ‘Immigrant as Pollutant’ in Media Representations of Immigration. Rhetoric and Public Affairs 11(4): 569–602.

Cohen S. (1972). Folk Devils and Moral Panics. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

CRB (2018). Orosz Állami Befolyás a Magyar Online Hírportálokra 2010–2017. Budapest: Corruption Research Center.

Entman R.M. (1993). Framing: Toward the Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication 43(4): 51–58.

Enyedi Z. (2023). Illiberal Conservatism, Civilizationalist Ethnocentrism and Paternalist Populism in Orban’s Hungary. Budapest: Central European University, CEU DI Working Papers 3.

Fengler S., Bastian M., Brinkmann J., Zappe A.C., Tatah V., Andindilile M., Assefa E., Chibita M., Mbaine A., Obonyo L. (2020). Covering Migration – In Africa and Europe: Results from a Comparative Analysis of 11 Countries. Journalism Practice 16(4): 140–160.

Gerő M., Pokornyi Z., Sik E., Surányi R. (2023). The Impact of Narratives on Policy-Making at the National Level. The Case of Hungary. BRIDGES Working Papers 22. https://www.bridges-migration.eu/publications/the-impact-of-narratives-o... (accessed 4 September 2025).

Goffman E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

Göncz B., Lengyel G., Ilonszki G. (2024). Identity, Pragmatism and the Future of Europe. An Exploration in Hungarian Media Discourses. Corvinus Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 15(3): 51–73.

Grimmer J., Stewart B.M. (2013). Text as Data: The Promise and Pitfalls of Automatic Content Analysis Methods for Political Texts. Political Analysis 21(3): 267–297.

Guriev S., Treisman D. (2020). A Theory of Informational Autocracy. Journal of Public Economics 186: 104–158.

Harris C.T., Gruenewald J. (2020). News Media Trends in the Framing of Immigration and Crime, 1990–2013. Social Problems 67(3): 452–470.

He W., Wu H., Yan G., Akula V., Shen J. (2015). A Novel Social Media Competitive Analytics Framework with Sentiment Benchmarks. Information and Management 52(7): 801–812.

Kahneman D., Tversky A. (1984). Choices, Values, and Frames. American Psychologist 39(4): 341–450.

Krekó P., Enyedi Z. (2018). Orbán’s Laboratory of Illiberalism. Journal of Democracy 29(3): 39–51.

Lawlor A., Tolley E. (2017). Deciding Who’s Legitimate: News Media Framing of Immigrants and Refugees. International Journal of Communication 11: 967–991.

Lázár D., Sik E. (2019). A Morális Pánikgomb 2.0. Mozgó Világ 11: 15–32.

Minsky M. (1974). A Framework for Representing Knowledge. MIT-AI Laboratory Memo. https://sites.cc.gatech.edu/classes/AY2013/cs7601_spring/papers/Minsky+1... (accessed 30 April 2025).

Mohammad S.M. (2016). Sentiment Analysis: Detecting Valence, Emotions and Other Effectual States from Text, in: H.L. Meiselman (ed.) Emotion Measurement, pp. 201–237. Sawston, Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing.

Németh R., Katona E., Kmetty Z. (2020). Az automatizált szövegelemzés perspektívája a társadalomtudományokban. Szociológiai Szemle 30(1): 44–62.

Pang B., Lee L. (2008). Opinion Mining and Sentiment Analysis. Foundations and Trends in Information Retrieval 2(1–2): 1–135.

Rakovics Z., Boda Z. (2025). Shaping Migration Discourse: A Text Analysis of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Speeches. Central and Eastern European Migration Review.

Sik E. (2016). Egy Hungarikum: A Morálispánik-Gomb. Mozgó Világ 10: 67–80.

Sik E., Gerő M. (2022). ‘Már Nyomni Sem Kell’ – a Morális Pánikgomb és a 2022. évi Választás, in: B. Böcskei, A. Szabó (eds) Az Állandóság Változása. Parlamenti Választás, pp. 65–86. Budapest: MTA Társadalomtudományi Kutatóközpont Politikatudományi Intézet.

Sik E., Krekó P. (2025). Hungary as an Ideological Informational Autocracy (IA) and the Moral Panic Button (MPB) as its Basic Institution. Central and Eastern European Migration Review.

Sik E., Simonovits B. (2019). The First Results of the Content Analysis of the Media in the Course of Migration Crisis in Hungary. Ceaseval Working Paper. http://www.tarki.hu/index.php/eng/ceaseval-working-paper-first-results-c... (accessed 14 February 2024).

Surányi R., Bognár E. (2025). Un)Deserving Refugees: The Migration Discourse in Hungary, 2015 and 2022. Central and Eastern European Migration Review.

Taboada M., Brooke J., Tofiloski M., Voll K., Stede M. (2011). Lexicon-Based Methods for Sentiment Analysis. Computational Linguistics 37(2): 267–307.

Torkington K., Ribeiro F.P. (2019). What Are These People: Migrants, Immigrants, Refugees? Migration-Related Terminology and Representations in Portuguese Digital Press Headlines. Discourse, Context and Media 27: 22–31.

Tóth M., Csatár P., Majoros K. (2018). Metaphoric Representations of the Migration Crisis in Hungarian Online Newspapers: A First Approximation. https://www.metaphorik.de/sites/www.metaphorik.de/files/journal-pdf/28_2... (accessed 2 May 2025).

Van Gorp B. (2005). Where is the Frame? Victims and Intruders in the Belgian Press Coverage of the Asylum Issue. European Journal of Communication 20(4): 484–507.

Verleyen E., Beckers K. (2023). European Refugee Crisis or European Migration Crisis? How Words Matter in the News Framing (2015–2020) of Asylum Seekers, Refugees and Migrants. Journalism and Media 4(3):727–742.

Copyright information

© The Author(s)

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.