Introduction

This article includes basic analytical considerations which led the author to systematisation of the existing knowledge about migration from Poland in the transition period, in a conceptual form of the incomplete migration. The theory itself has already been presented in earlier author’s works (Okólski 2001a; 2001c). More important, the theory of incomplete migration had earlier become the fundamental conceptual premise of the research programme pursued by the Centre of Migration Research of the University of Warsaw (CMR) that began in the mid-1990s. It was first thoroughly examined and empirically tested in the late 1990s when the CMR experimented with the ethnosurvey approach to migration study (Jaźwińska, Okólski 1996; 2001; Frejka, Okólski, Sword 1998), and later substantially modified and used as a theoretical background in further CMR projects (e.g. Kaczmarczyk 2008; 2011).

The migration phenomena observed during the transition period in Poland have their roots in the rather distant past – the circumstances following the Second World War or even earlier. The same can be said of the primary type of international mobility of Polish citizens at the beginning of the 21st century, a phenomenon I call incomplete migration.1

The concept of incomplete migration is defined more precisely later in this article. As a working definition, it can be considered a form of international labour mobility of a certain category of people who did not join the initial mass outflow from rural to urban areas in the industrialisation period.2 As a result, and because of specific historical and regional circumstances, they were more or less trapped in their original places of residence, despite the structural unemployment which typified local labour markets. The surplus rural and small-town labour force first engaged in mass circular migration to nearby industrial centres. With time, however, many of these people – increasingly followed by others from different social backgrounds – started to earn money from trips abroad. These trips largely supplanted commuting and performed some of the same functions.

To consider ‘industrialisation’ as one of the circumstances leading to incomplete migration is to risk over-generalisation. By industrialisation I mean a fundamental and abrupt change in the economic structure – a transition from a predominantly agricultural economy to one where most of national product is generated by industry. Such a meaning is undoubtedly Eurocentric and somewhat misleading even with reference to Europe, as it overlooks (for example) regional differences between and within national economies. However, it seems applicable to Poland.

Industrialisation in Poland was completed only after the Second World War, under the communist regime. Previously there had existed only isolated localities with an ‘industrial’ economic structure. Creating industrialised areas was – it must be emphasised – a difficult task.3

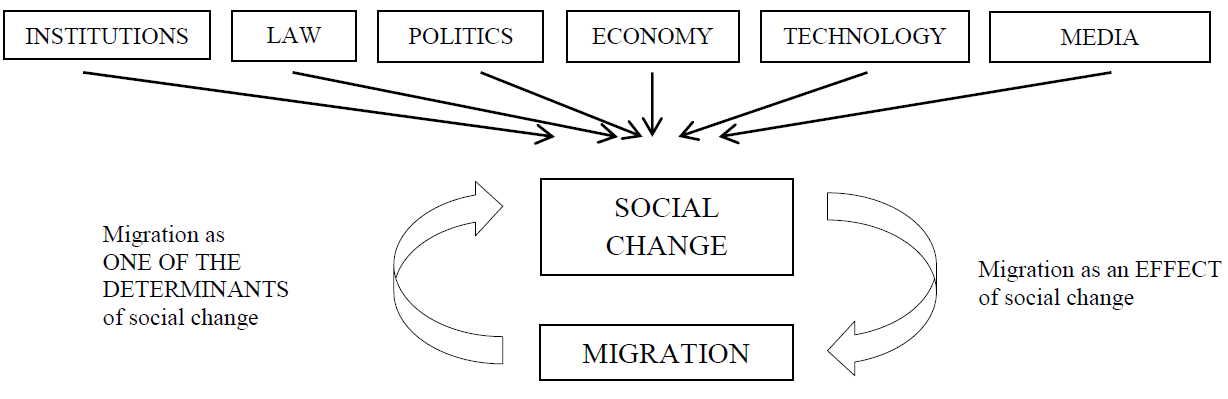

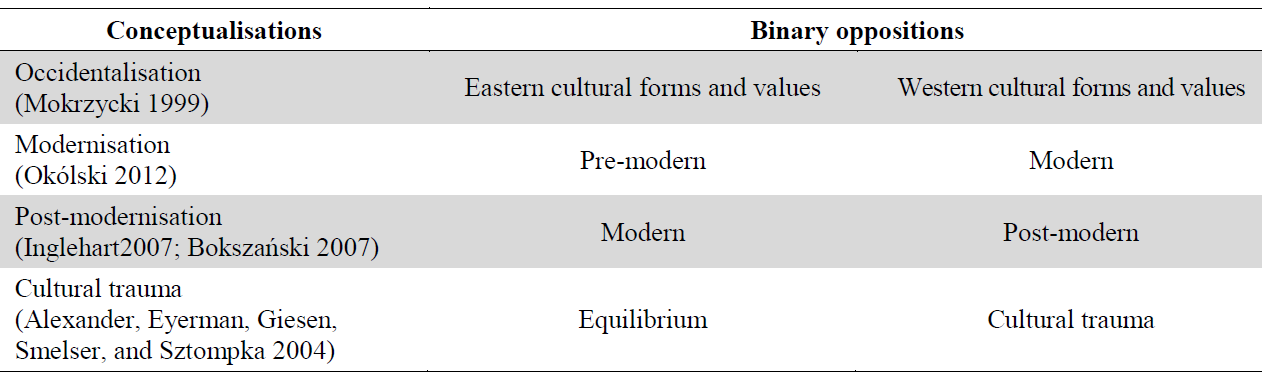

The impact of industrialisation on the mass outflow of people from rural to urban areas had been at the very least significant, if not decisive, in many West European countries. This has led scholars to suggest the existence of a number of universally observable features of spatial mobility. Generally, these have been considered part of the modernisation process (although other terms are sometimes used). Many researchers of human mobility during the period of European industrialisation have assumed the existence of a specific paradigm, according to which traditional society was characterised by very limited mobility, including spatial mobility,4 and it was modernisation which stimulated mobility in all its aspects – social, occupational and spatial.5

Accepting such a point of view is a short step from formulating the general ‘law’ that a highly immobile traditional society inevitably transforms into a highly mobile modern one. This is particularly evident if we take into account the once popular but now somewhat forgotten theory of convergence (Bell; Rostow), or newer ideas of universalisation (Fukuyama) or globalisation (Robertson). The approach has been adopted by many contemporary researchers of social change, including migration scholars.6 What is more, some have asserted that these laws describe permanent and irreversible trends (Goldscheider 1971; Zelinsky 1971), even unidirectional ones (Ipsen 1959; Davis 1974).7 This in turn led one critic of the approach to refer to such laws (not unsympathetically) as ‘beliefs’ (Hochstadt 1999).

This specific modernisation paradigm applied to contemporary population flows has met with growing disapproval among many researchers. Such scholars typically question the universal and generalisable nature of migration trends by supplying examples – from various social and cultural environments, and from different epochs and geographical locations – which suggest that spatial mobility is relatively strongly influenced by specific factors, whose impact is more important than that of universal ones.

Over the last few years, since this controversy has led to a deep rift among migration scholars, it has been difficult not only to find common ground, but even to discuss the arguments on both sides. Therefore, it seems reasonable to engage in a short digression.

On the one hand, contemporary anthropological and historical scholarship allows us to state that migration should be considered to be a normal, structural and ever-present element of societies throughout history (Lucassen, Lucassen 1997). In particular, migration is not a sign of modernity, but an inherent part of social and economic human organisation.8

On the other hand, in the period directly preceding industrialisation, societies of Western Europe were undeniably predominantly agrarian – the majority of their populations lived in rural areas, were employed and made a living in agriculture. By contrast, 100-150 years after industrialisation began, rural populations were a clear minority in every country. This conclusion is not invalidated by the differences persisting between these countries or indeed inside them, even by the continuing existence of agrarian enclaves in some countries. Nor is the conclusion invalidated by the phenomenon of increased urban-rural migration in this period, because such migrants did not usually seek employment in agriculture, and certainly did not make a living out of it. Moreover, they maintained close ties with urban cultural and economic life. This change could not be brought about by a radical decline (to negative value) in natural increase rate of the rural population, or a much lower growth rate than the urban one. On the contrary, it was the result of a massive, frequently abrupt outflow, indeed an ‘exodus’ of the rural population into towns and cities.

This migration was a symptom as well as an effect of modernisation, and at the same time a means of achieving social mobility. It was due to several important factors.

First, migration became possible and widespread because of political and socioeconomic changes brought about by modernisation. Some early regulations (rugi, the historical practice consisting of evicting peasants and taking possession of their farmland, common in Poland in the 19th century; or the process of enclosure) all but forced the population into urban areas.

Second, fundamental changes in the economy, extraordinary technical progress and an increase in labour productivity gradually pushed out the labour force from sectors with fading or insufficient labour demand, i.e. usually away from rural areas and the small towns servicing them, and towards sectors with increased or unsatisfied labour demand, i.e. predominantly big cities. One example of this process is the collapse of small-scale production in rural areas, which was unable to compete with urban factories.

Third, the modern development of the social division of labour called for a quick turnover of a flexible and adaptable labour force from different occupations and with different skills, whose inflows were governed by impulses coming from the labour market, which covered ever-growing areas or indeed became partially internationalised.

Finally, demographic transition not only led to a massive increase in population, but also contributed to significant territorial disproportions in population, and resulted in relocation of demographic resources, to places with better livelihood opportunities.

Also of importance for the phenomenon is the already-mentioned settlement structure at the onset of the modernisation period, which was characterised by an overwhelming majority of rural population in the overall population. This is why an initially large, although not predominant, part of the population growth due to demographic transition was concentrated in rural areas. And even though – as a consequence of outflows to urban areas – the proportion of rural population in the overall population gradually decreased, the absolute surplus of rural over urban frequently increased, despite the fact that usually the symptoms of demographic transition manifest first in urban contexts and are more intensive there.

The exodus of the rural population due to modernisation in western European societies was aptly described by the hypothesis of the mobility transition (Zelinsky 1971). Initially, the outflow from rural to urban areas, which, according to the hypothesis, is one of the five types of spatial mobility (some authors claim that the list is incomplete),9 was steadily increasing and, with the development of migrant networks and ensuing chain migration, assumed a mass scale. At certain point, however, the momentum of the outflow was reached and the stock of potential migrants started to shrink. The number of new migrants gradually decreased, and when it became close to zero, the level of saturation was reached.10 Major determinants of that process were the ‘pull’ forces of industrialisation,11 on the one hand, and the push forces related to large demographic resources of rural areas and growing labour productivity in agriculture, on the other.

As has already been suggested, in Poland, the nature of the changes in the post-war economic structure seems to invite comparisons with the West European model of industrialisation. Given that at the onset of those changes, around two-thirds of Poles lived in rural areas and found employment in agriculture, it seems reasonable to assume that the population outflow could have been similar to the one in Western Europe. Because of that, we can assume that we are justified in applying the model of mobility transition, particularly the part that describes migration from rural to urban areas, to interpret the phenomenon in Poland. This approach will be adopted in the following analysis.

‘Socialist industrialisation’ and migration from rural to urban areas

The aim of post-war industrialisation in Poland, until recently often labelled ‘socialist’, was to make up relatively quickly for Poland’s having fallen behind. Hence the rapid industrial growth and high levels of capital accumulation. This strategy was initially realised through investment in branches such as mining, steel production, metallurgy, machine-building and transport. The scale and concentration of the investments were usually large, and moreover localised in a few industrial centres and urban areas.

At the time, labour demand in cities was growing, and by far exceeded supply. At first, many migrants who settled in industrial centres came from other urban areas, often destroyed during the war or annexed by the USSR, or from overpopulated small towns.12 The sizeable, though relatively decreasing, mobility of the urban population during the period of socialist industrialisation is evidenced by the fact that only in the first half of the 1950s did more people move between different urban areas than from countryside to city. Over time, the flow from rural areas to industrial centres gained in significance.

At that time, rural areas suffered from a surplus of workforce usually rather low skilled, and this was precisely that kind of labour which was in high demand in cities. This imbalance on the labour market proved to be an extremely influential factor in the increased mobility of human resources, and contributed to the mass outflow of people from rural to urban areas, which accelerated urbanisation in Poland.

Immediately after the Second World War, attempts to stimulate orderly and comprehensive urbanisation translated into official plans to create industrial centres and recruit the labour force from other regions, as well as to build housing estates and service infrastructure. However, the plans were nowhere brought to completion and were never widespread. Despite the lack of consistency in this area, from the mid-1940s and for two decades afterwards, the population flow into urban areas was exceptionally dynamic.

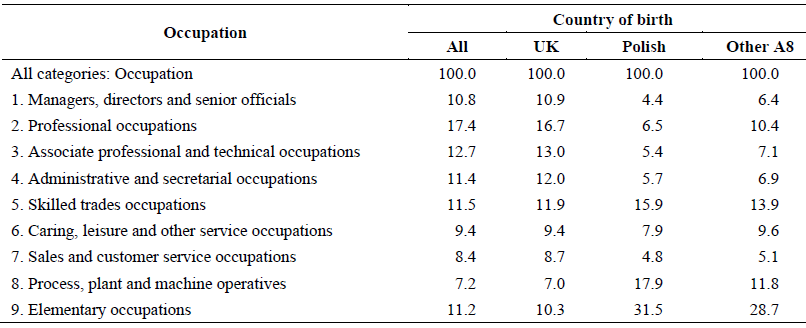

During the period of socialist industrialisation, several million people moved from rural to urban areas; in the years 1951-1970, their gross number was over 6 000 000 and the net number, over 2 000 000. In a relatively short time, the share of rural population decreased dramatically, from ca 66 per cent in 1946 to ca 48 per cent in 1970. It would seem that Poland, like Western Europe before, experienced the modernization-related migration cycle described in the hypothesis of the mobility transition.

It is important to note, however, that with the exception of the initial period of industrialisation, i.e. until ca 1960, the inflow of labour force from rural areas did not keep pace with the increase in their employment in urban areas. For example, in the 1950s, the increase in rural population of working age was greater than the increase in employment outside agriculture (on average, by 37 000 a year), whereas in the 1960s it was smaller (by 16 000 a year, on average). On the other hand, in the 1950s, the labour force who settled in urban areas (including the newly arrived migrants) occupied up to 70 per cent of the newly created jobs outside agriculture, whereas in the 1960s the share was only 58 per cent (Fallenbuchl 1977).

Territorial mobility of young workers (i.e. the economically active population between 30 and 39 years of age) was usually rather limited. In 1972, 41 per cent of them had not moved since their 15th birthday. Low mobility was particularly visible among the inhabitants of big cities (with the population exceeding 200 000), where the proportion reached 76 per cent, while among inhabitants of villages and small towns (up to 5 000 inhabitants), those who did not move were relatively few in number (33 per cent). If we compare the first 20-25 years after the Second World War with the following 15-20, we can see that the young and naturally relatively mobile labour force became significantly less prone to migrate. If we define as mobile the people who have independently changed their place of residence at least once after their 15th birthday, then we can conclude that, in 1972, 59 per cent of Polish workers (i.e. economically active people) aged 30-39 were mobile, whereas in 1987 their share decreased to 44 per cent.13 The main factor responsible for the decrease was the declining mobility of the rural population. Survey evidence indicates that in 1972 the rural population participated in 73 per cent of all internal migration, whereas in 1987, the figure was only 68 per cent. What is more, in 1972, 22.5 per cent of the surveyed population who had lived in rural areas at the age of 15 resided in urban areas; by 1987, the share had decreased to 15.5 per cent (Węgleński 1992).14 Therefore, the decrease in migration, which had never been exceptionally large to begin with and was accompanied by numerous cases of return migration, was caused mainly by the diminishing outflow from rural to urban areas.

Under-urbanisation – its causes and effects

It turns out that ‘mobility transition’ in Poland, at least as far as the above-mentioned population movements are concerned, was very different in character from the one observed in the western part of the continent and described in Zelinsky’s hypothesis. Socialist industrialisation may have triggered mass inflows of labour force into the growing industrial centres, but, unlike the Western precedent, it did not lead to a mass movement of surplus labour force from villages and small towns to urban areas. One of the main reasons for this difference was that pressure (not to mention, coercion) to migrate was not exerted upon the ‘free’ labour force in this part of Europe (Turski 1965). This effect of industrialisation is common to all countries of Central and Eastern Europe and results in a level of urbanisation which is significantly lower here than in Western Europe, if we take into account the similar level of industrialisation in both regions (Ofer 1977).

In the literature, under-urbanisation15 is perceived as an inevitable, though largely unintended, effect of the rapid expansion of industrial production in a centralised totalitarian state (Konrad, Szelenyi 1974). At its source are the socialist central planners’ attempts at ‘economising on urbanisation’ (Ofer 1977). Such attempts resulted from two phenomena: the relative economic backwardness at the onset of socialist industrialisation; and the doctrinarian and ideology-biased approach towards the strategy of economic growth (Dziewoński Gawryszewski, Iwanicka-Lyrowa, Jelonek, Jerczyński, Węcławowicz 1977; Regulski 1980; Kukliński 1983).16

The backwardness was evident e.g. in the fact that the economy was dominated by a great number of small, barely commodified peasant farms, and in the large surplus of labour concentrated in small towns and rural areas. Unlike in big cities, where employment opportunities were great, the development strategy used in rural areas consisted in attempts to keep most of the surplus labour force in agriculture. In towns, the adopted strategy required considerable capital expenditures in relation to labour resources (Ofer 1977). What is more, the urban infrastructure, under-financed, meagre, and ravaged by war-time destruction, made it impossible to suddenly accommodate large numbers of new inhabitants.

However, the socialist doctrine of economic development implied a competition with, and a quick victory over, the capitalist economy. This was only possible in the context of rapid and wide-ranging growth. In a situation of a self-imposed isolation from the world and relative autarky, the only source of growth could be internal accumulation, i.e. the country’s own extremely meagre capital.17

Among the many dilemmas faced by socialist planners, a fundamental one concerned the allocation of the available funds: in industrial investments, i.e. directly into industrialisation, or into reconstruction and development of the urban infrastructure and services, i.e. urbanisation. On the one hand, doctrinal reasons suggested that the main aim of investments should be to boost production, and on the other, historical reasons, i.e. a strongly ‘agrarian’ economic structure, made it possible to keep a large part of the surplus small-town and rural labour force in its traditional place of residence. The temptation was, as it soon turned out, too great to resist (Turski 1965; Konrad, Szelenyi 1974; Węgleński 1992).

‘Economising on urbanisation’, or rather on keeping it in check, was therefore the result of a rational choice made by the authoritarian state, unhindered by the complexities of democratic mechanisms. The state, in its attempts to maximise the rate of industrial investment, perceived urbanisation-related social costs as a burden and strove to minimise them. The main victim of this choice was housing development.

However, the planners, in their illusion of rational reasoning, were unable to control or indeed predict one of the objectively immanent characteristics of a centrally planned economy – ‘the soft budget constraint’ (Kornai 1986). This was responsible e.g. for the fact that in the so-called production sphere of the economy (industry in particular), labour demand was practically unsaturated. State enterprises were known for maintaining a level of employment which greatly exceeded the production needs at any given time (Rutkowski 1990).18 As a result, the forces which pushed people out of small towns and rural areas to work in industrial centres were in a way artificially created. Such a mechanism, however, did not operate in the non-production sphere, e.g. municipal or household services sectors. One may therefore conclude that the actual insufficiency of the urban infrastructure was the result not only of a conscious and rational under-urbanisation strategy, but also of excessive employment in industry.

The huge labour force demand in big cities, given their insufficient infrastructure, and lack of housing in particular, made it necessary to import employees who accepted that they could not settle in close proximity to their workplace or, in some cases, were not inclined to move at all. There were three principal forms of this arrangement: a) regular employment coupled with daily commuting, b) regular employment coupled with temporary stays in makeshift conditions (living in lodgings or sharing a room in a workers’ hostel, etc.) close to the workplace, with weekly visits to the family, and c) irregular employment (e.g. seasonal or exclusively out of season), coupled with weekly commuting and living in makeshift conditions close to the work-place during the week (or with some other form of commuting or living arrangements).19

Commuting was the most popular choice. It seems that the planners who decided to save on urbanisation were aware of the solution’s serious social costs. However, it appears that investments in transport infrastructure were considered overall to be cheaper than investments in urban infrastructure (Dąbrowski, Żekoński 1957). What is more, the former seemed less technically and organisationally complex, and took less time to build. It was therefore decided that the state was going to invest in roads and railways leading to big industrial centres. What is more, many factories in these centres were supplied with their own means of transportation for the use of their employees. Commuting was free or heavily subsidised (Turski 1965).

This macro-economic argument – which supports the idea of employing non-local or temporary workers in industrial centres rather than having them settle in urban areas – is not the only one. Others are more micro-economic in nature, and have a common denominator – the minimal wage required to support the employee and the members of his or her household (Herer 1962).

There are three factors which best explain the low living costs of worker families and which are the most relevant to the strategy under discussion (Chołaj 1961; Dziewicka 1961; Sokołowski 1960). First, workers who commute or who have a temporary place of residence pay relatively little for lodgings. Second, their other basic expenses (food in particular) are also significantly lower than for other employees. Third, non-local workers tend to accept harsher living conditions more easily: a general characteristic of people who are socially or geographically mobile. All this is conducive to keeping wages at a relatively low level,20 but it also helps limit labour costs on a macro-economic scale and to reduce aggregate demand, and therefore (in the conditions of chronic shortages of many products on the market), to decrease the pressure on consumer goods supply. What is more, it is a typical example of the logic of socialist industrialisation.21

The above-described, gradually intensified strategy resulted in diminishing migration from rural to urban areas and an increase in the number of commuters and people who chose other, non-residential forms of mobility, and, therefore, a gradual change in the balance between the scale of migration to big cities and of short-term moves, especially circularity (Fuchs, Demko 1978).

What would make so many people who were economically redundant in their place of residence accept the offer of a life which was permanently divided geographically, and usually marked by temporariness? After all, in many cases, by doing this, they also gave up any opportunity of substantially improving their quality of life. To use a category developed in one well-known migration theory: risk diversification as a household strategy seems to have been a strong motivating factor for commuters and casual workers.

Small town and, particularly, rural residents employed in big cities came from households whose members usually had other and frequently diversified means of support, often largely uninfluenced by state planning and regulations. For these employees, their earnings in industry were like social benefits, a valuable addition to the money earned in their own workshop, shop, garden, and above all, their family farm. In particular, self-provisioning in agricultural produce meant that workers were not at the mercy of changes in supply and prices on the market. Occasionally they took advantage of such changes to sell their produce on the black market, including in the city.

In industrial centres, non-local employees from farming families valued their ability to make free choices on the labour market, especially the ease with which they could give up their urban job when there was a lot of work on the farm, and then find employment again. It must have also been important for them that they could slack at their factory job without fear of sanctions (Turski 1961).22

In light of these arguments we can assume that the factors which impeded migration from rural areas and villages to urban areas23 became stronger with time,24 and the reasons to find employment outside one’s permanent place of residence and living environment became more firmly grounded. This had a strong impact on actual spatial mobility.

We should also be aware that in Poland, the change in balance between the volume of migration to cities and the scale of circularity, posited by the hypothesis of the mobility transition, took place in different circumstances and had different causes than the similar phenomenon observed earlier in West European countries. In Western Europe, the shift to large-scale circulation only happened when agriculture became a marginal sector of the economic structure and when most of the population previously employed in agriculture had moved from rural to urban areas. People who circulated between urban and rural areas were usually those who, in search of more favourable living conditions, had earlier chosen to move from densely populated and polluted industrial centres to the environs of urban areas, but nevertheless continued to work in the city and maintained their urban cultural identity (Fuchs, Demko 1978; Wiles 1974).

In Poland, however, the abrupt increase in circularity between rural and urban areas was observed in a situation when more than half of the population still lived in the former. The process concerned mostly workers who were redundant in their places of residence, usually members of peasant households. Therefore, whereas in the West circularity appeared after the mass outflow of redundant rural population to urban areas had dwindled away and, to a certain extent, when migration stopped being a viable source of labour, in Poland the two processes coexisted and, what is more, circularity largely replaced migration.

The peak and decline of commuting

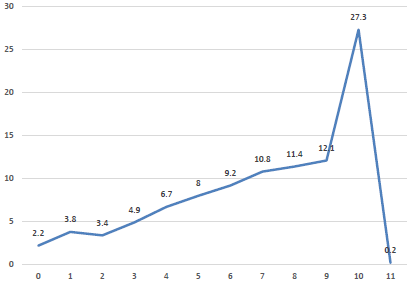

At a cautious estimate, by the beginning of the 1950s ca 500 000 people commuted to work, and the number kept rising until the beginning of the 1970s. The dynamics of the phenomenon is evidenced by the number of monthly train tickets, which rose from 93 000 to 501 000 in the years 1947-1956 (Turski 1965). Later, commuters were counted directly. In the years 1964-1973, their number rose from 1 500 000 to 2 800 000, which reflected an increase from 20 to 27 per cent in the number of commuters among all non-agricultural workers (Fallenbuchl 1977).25 In some voivodeships, already by the 1960s their number amounted to 35-40 per cent (Dobrowolska 1970). In order to fully convey the scale of, so to speak, unfulfilled migration from rural to urban areas, we would have to include all the members of the commuters’ families, the people staying in workers’ hostels or lodgings, and those occasionally employed in big cities, of whom at least some had rural origins. In the 1950s, the number of people living in workers’ hostels was estimated at around 1 500 000 (Dyoniziak, Mikułowski-Pomorski, Pucek 1978).

Some estimates show clearly that a large majority of commuters came from rural areas, from 70 to 80 per cent depending on the region (Dobrowolska 1970). A particular sub-group of the commuters were people with two occupations, colloquially referred to as peasant-workers (chłoporobotnicy in Polish), i.e. part-time farmers, part-time factory workers. They were regularly employed outside agriculture, usually in big industrial centres. However, they lived in rural areas, on their own family farms, where they helped around as well – after their regular hours in the city, on their free days, and during holidays or leaves of absence, not always acquired legally. They would often e.g. abandon their factory job during periods of intensive field work, malinger or supply fake doctors’ notes.

An unprecedented increase in the number of these peasant-workers, from 500 000 to 1 400 000, was observed between 1950 and 1970. Their overall share in the workforce also increased, from 4.5 per cent in 1950 to 6.7 per cent in 1970 (Fallenbuchl 1977).

The first peasant-workers (80 per cent in 1950) overwhelmingly came from households with small farms (up to 2 ha), but later they were increasingly joined by those who owned more land (Bajan et al. 1974).26 This was undoubtedly largely because from the 1950s a significant proportion of surplus farm workers from small farms were already commuting to work outside agriculture.27

Commuting, usually from rural to urban areas, was a mass phenomenon for a relatively long period of over 20 years. It made many farm workers and their household members28 very fluid and flexible in their choice of jobs, and the trait was then passed on from generation to generation (Czyżyk 1987).

As a result, by the early 1970s, two phenomena related to under-urbanisation had become well established and more or less permanent: the prevention of huge masses of the redundant rural (and small-town) population who regularly earned money in cities from moving there, and circulation as practically the only means (form of mobility) leading to the gainful employment of that population.29 This had a number of important consequences which were probably not factored into the costs of the industrialising strategy.

Many of those consequences can be summarised as follows: a whole category of people, torn between living and working in the village or small town, and living and working in the city, were permanently marginalised, both economically and socially. It has been already noted that such people were usually inclined to accept low pay and poor working conditions. What is more, we can assume that they had fewer opportunities than other workers to participate in the management and supervising of teams or organisational units. It was probably also true of careers in local politics, in state administration or in trade unions, all very important at the time. They also did not participate in vocational training and were not promoted as often as their co-workers living in cities. It must surely have made them feel deprived and alienated (Turski 1961).

The reasons for this state of affairs, both ‘technical’ and cultural, were obvious. Commuters were usually rooted in a different cultural environment, sometimes considered anachronistic in their workplace, and their behaviour and attitudes were typical of this environment. They were frequently stressed by the lack of stability in their private lives; they had much less free time, further reduced by their long journeys between home and workplace; and, finally, in case of many the hard physical labour on their farms contributed to their state of constant tiredness.30

Since they usually came from environments with limited access to secondary and higher education, their level of education was often low, and their vocational qualifications were frequently minimal when they first took up employment in the city. All these factors resulted in the very low value of the commuters’ labour, doomed them to the ranks of the lowest-skilled manual workers, and impeded promotion and social mobility (Konrad, Szelenyi 1974).

On the other hand, with time, inhabitants of rural areas employed in big industrial centres learned to deal with the unfavourable conditions and to adapt (Czyżyk 1987). For example, they could permit themselves to make less effort, be less productive, less disciplined, and less loyal towards their employer than other employees. Many of them became used to their freedom on the labour market and were satisfied with frequent job changes interrupted by periods of voluntary unemployment or freelancing. This was only possible because of the huge labour demand in big cities which well exceeded the supply (Beskid 1989). What is more, until the 1990s, a low-skilled worker could ‘wait out’ unfavourable conditions in the labour market on his or her family farm (Socha, Sztanderska 2000).

Finally, as already suggested, the choice made by the people who did not manage to migrate to their primary place of employment reflected the combined strategies of their own households. Their goal – as is typical of periods of social transition, including mobility between a relatively traditional and a relatively modern environment – was to split risk and role attribution, and to diversify sources of income between household members, which often allowed them to cope better with harsh living conditions typical of an inefficient totalitarian state. Moreover, a strong identification and real bonds with their households, often made up of several generations or even several families, gave commuters and other unfulfilled migrants moral, psychological and material support (Turski 1961).

To sum up, the post-war period saw the emergence of a relatively numerous segment of society which had one permanent characteristic – the ability to live away from the workplace (or to travel a long distance to work), and to stay relatively isolated from the more socially and economically developed and more culturally attractive big-city environment. In addition, fundamental socio-political and economic mechanisms led to the perpetuation of the phenomenon until the beginning of the 1970s.

The initial development strategy imposed in Poland and other countries by the former USSR was later unintentionally modified in many respects (due to the weakness of the authorities as well as their pragmatic approach). The most important of these modifications, and key to the present analysis, was the partial abandonment of plans to socialise or nationalise all property. It contributed to the preservation of the semi-traditional peasant sector in agriculture and, as a consequence of industrial growth, to the emergence of peasant-workers on the labour market.

However, this was not the only significant modification. Already from the mid-1960s onwards, it became clear that further investment expansion favouring production over consumption would cause rising tension. One of the sources of such tension was huge and rising energy consumption and the rate of consumption of raw and other materials in the national economy. Within the geopolitical constraints of the time, the tension could only be relieved by further investments, leading to even more intensive acquisition of raw materials and energy generation, which not only resulted in an extremely wasteful economy but also created a vicious circle (Kondratowicz, Okólski 1993). In this situation, the informal economy flourished as a buffer of the formal economy, reducing individual imbalances and neutralising workers’ frustrations.

The worker protests of December 1970 made possible a change of the state (communist) leadership and an ensuing radical overhaul of the economic strategy. It marked the beginning of restructuring and reconstruction in industry. New technologies were introduced, and more was invested in the production of consumer goods, including those requiring a high degree of processing. The main investments were often in modernisation, e.g. the purchase of new equipment or assembly lines. Less was spent on building new plants, unlike in the previous period. This led to a reduction in the overall demand for labour,31 while an increase in wages led to higher labour costs. A major cause of this change was Poland’s greater openness to the West. At the same time, parallel but informal social structures and institutions flourished. The new situation was best described by Bartłomiej Kamiński, who coined the term ‘withdrawal syndrome’ to describe the weakened state’s failure to fulfil its constitutional obligations and its surrender of important prerogatives. At the same time, increasingly empowered citizens cut ties with ‘official’ institutions and established new organisations, informal structures and forms of participation (Kamiński 1991).

Soon after the onset of the changes in industrial structure and the related investment strategy, the demand for low-skilled labour began to dwindle. The first victims were those with weak links to their workplace, seasonal workers and employees with poor discipline records. Peasant-workers were a group hit particularly hard by the changes.

In addition, the authorities’ decision to open up to the West, coupled with attempts to attract direct foreign investments and with running up a huge foreign debt, came at an unfortunate historical moment. In 1973, the economy of that whole part of the world entered a recession period and underwent restructuring. The Polish economy could not remain unaffected. The economic situation worsened first in 1976, then again in 1978, this time very dramatically and, one could say, definitively. As a result, despite the initial economic upturn, the 1970s were a period of diminishing demand for unskilled labour, especially construction workers or those who were a surplus or reserve labour force in nationalised enterprises. Many enterprises reduced recruitment and transport services or even gave them up entirely.

Commuting became visibly less popular,32 especially among peasant-workers.33 Probably from 1 000 000 to 1 500 000 people were at a risk of losing their job in cities, and many of them did indeed become unemployed. Many found themselves in a kind of limbo, not only because their migration to urban areas had not been fulfilled, but also because its completion was unlikely in the foreseeable future, and it was impossible for them to go back to productive work in agriculture or on the rural labour market in general.34 What is more, the earlier systematic marginalisation of commuters as well as the personal characteristics they had come to adopt were a serious burden. The traits that had allowed them to effectively function on the peripheries of the labour market in a wasteful and ideology-driven centrally planned economy turned out to be useless in the new economic situation.

Opening to the West and territorial mobility of the population

At the beginning of the 1970s, crossing the Polish border was simplified not only for (foreign) capital and goods, but also for people. Generally speaking, it was easier to obtain a passport, because the procedures became more liberal and applicant-friendly35 thanks to several new institutional changes.36 New national agencies were established to organise Polish citizens’ employment abroad. At the same time, bilateral agreements were signed with numerous countries concerning the export of Polish workers, and recruitment of suitable employees was carried out. From 1974, Polish citizens could obtain a passport without any special circumstances, and for travel to other socialist countries they did not need a passport at all, but could use an ID card, which was issued to all citizens (Matthews 1993). This meant that in practice one could travel abroad on one’s own with no additional formalities other than a proof of owning a foreign currency bank account or the required invitation from a foreigner. In 1970, ‘tens of thousands of people’37 who identified as German were allowed to emigrate to the Federal Republic of Germany, followed by 120 000 - 150 000 in 1975 (Łempiński 1987). In the second half of the 1970s, travel agencies specialising in group tours to foreign countries were established. All this added up to the ending of formal travel restrictions for Polish citizens, although for its own reasons the police maintained the right to refuse a passport (and therefore, the right to travel abroad) in certain circumstances (never revealed to the public).

There were also some partially institutionalised factors which helped citizens afford financially to travel abroad despite their low wages, and even to benefit financially from their travels.38 First, rail, aeroplane and ferry tickets for Polish citizens travelling abroad were ‘cheap’, paradoxically so, given their similarity to international fares. This was due to the official exchange rate of the Polish zloty to Western currencies. The latter were extremely underpriced, between 10 and 20 times cheaper (up to over 20 times in some periods) than their actual purchasing power. Second, Poles travelling abroad could buy in the National Bank of Poland a limited amount of very cheap foreign currency, and sometimes also very reasonably priced hotel, petrol and other vouchers.39 Third, the black currency market was tolerated by the authorities (to say the least!), which made it easy to buy and sell foreign currencies.40 Fourth, there were some newly-established national chains of shops where Poles could sell goods brought from abroad.41 Some of them had branches even in small towns whose population often travelled abroad. On the other hand, goods (including those made for export in Poland) unavailable in other retail shops were sold in specially designated chains of shops (Baltona, Pewex) for the foreign currencies transferred to Poland or personally brought home by Polish tourists. In time, they became a factor pushing people to seek employment abroad, since shopping in Baltona or Pewex became a sign of social status and prestige.42

The common denominator of all those solutions which pushed Poles to seek sources of income abroad was the malfunctioning of the authoritarian and centrally planned economy, with its chronic inability to satisfy the population’s needs, its shortages and the low purchasing power of the zloty in relation to Western currencies. This malfunctioning made it very profitable to travel abroad,43 and the profit was always calculated in relation to the black market price of the US dollar.

The emergence of this set of circumstances or institutions could be perceived as the ultimate proof of the planners’ weakness, their inability to solve many of people’s minor but nonetheless annoying problems. However, it could also be taken as evidence of their pragmatism.44

All these circumstances undoubtedly encouraged Poles to travel abroad, all the more so because they had long experienced acute isolation and now felt the need, hitherto artificially suppressed, to explore and ‘see the world’.

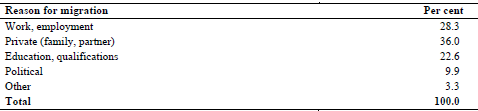

Therefore, it is not surprising that the 1970s were a time of increased international mobility, although, paradoxically, official emigration data of the time indicated a decrease in the number of foreign journeys. In addition to numerous tourists visiting family and friends or sight-seeing in organised groups, several tens of thousands of people found employment abroad, and a similar number emigrated to the Federal Republic of Germany owing to a special family reunification programme. Equally numerous were those who failed to return to Poland before the expiry date on their passport, which made them ‘illegal emigrants’ in official jargon. Based on many personal accounts of participants in such mobility, we can conclude that tourist trips – the most common form of international mobility at the time – gradually transformed into business trips, or a mixture of business and tourism. On the other hand, the migration flow seemed largely to make use of connections and follow older routes which had been very popular before the Second World War and in the immediate post-war period.

At the time, most people travelling abroad came from Warsaw and other big cities. They were the nation’s elite, the rich, the more educated, those who had travelled and seen the world, and who were therefore more willing to take the risk of travelling to unknown parts. In cities it was also easier to get the information necessary to fulfil all the formal requirements and, importantly, to use personal contacts to help obtain a passport.45 However, from the very beginning, in the 1970s, big-city travellers were joined by provincial pioneers (Frejka, Okólski, Sword 1998).

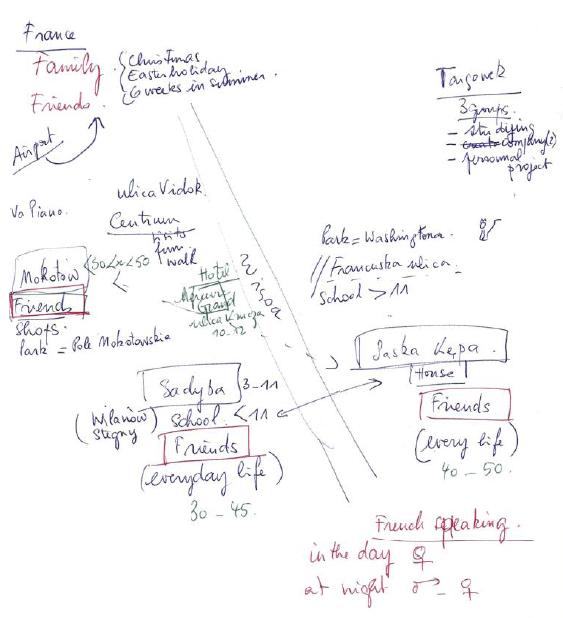

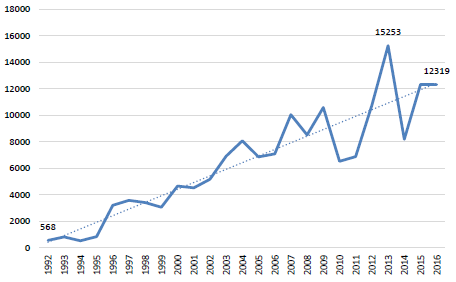

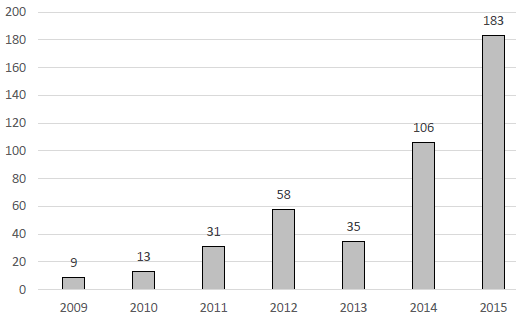

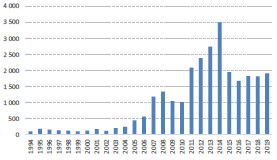

Research conducted at the Centre of Migration Research of the University of Warsaw shows that the mid-1970s were the watershed in foreign travel. Before then, migration from such well-researched peripheral regions as Podhale, Podlasie and Silesia (and even, to a certain extent, Warsaw) were sporadic and demonstrated no clear tendencies. After 1975, migration steadily increased (Jaźwińska, Łukowski, Okólski 1997).

Nevertheless, the volume of international migration rose sharply only in the years 1980 and 1981, mostly due to the suddenly much tenser political situation in Poland. The state administration made the procedure of obtaining a passport much simpler, and some Western countries dropped their visa requirements for Polish citizens. A range of countries introduced special protective clauses that ensured basic assistance and the right to a relatively long stay for Poles. With unprecedented speed and often bypassing official procedures, the Federal Republic of Germany welcomed tens of thousands of Polish tourists who declared German nationality.46

After the introduction of martial law in Poland in 1981, foreign countries granted asylum and refugee status or long-term transit permits to many Polish citizens who found themselves on their territory at the time. However, the event resulted in more restrictions regarding travel aboard.

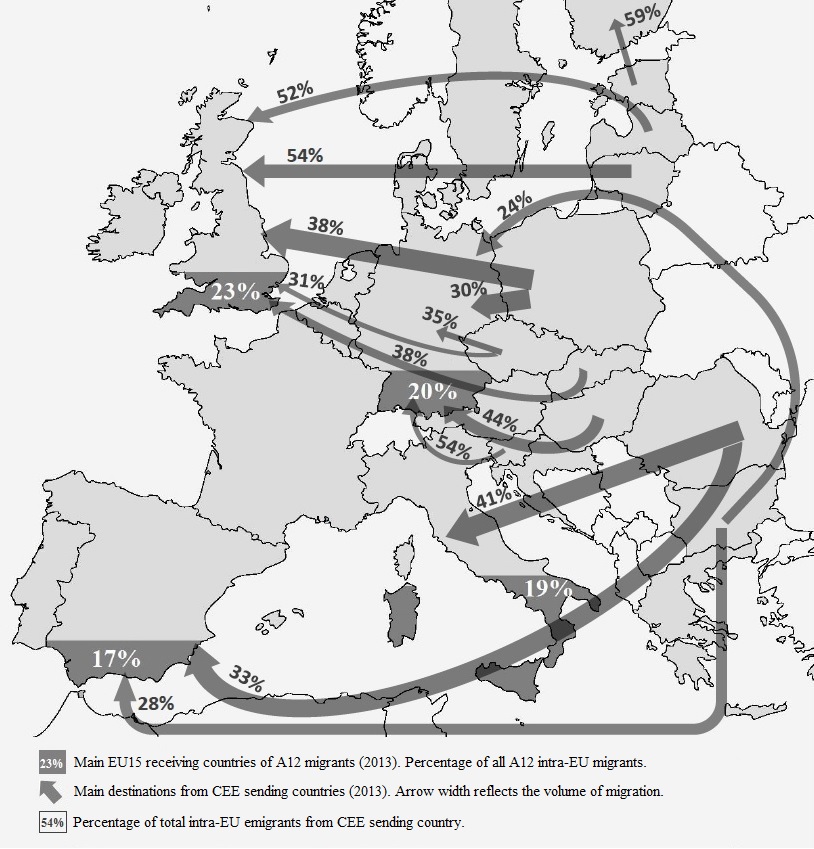

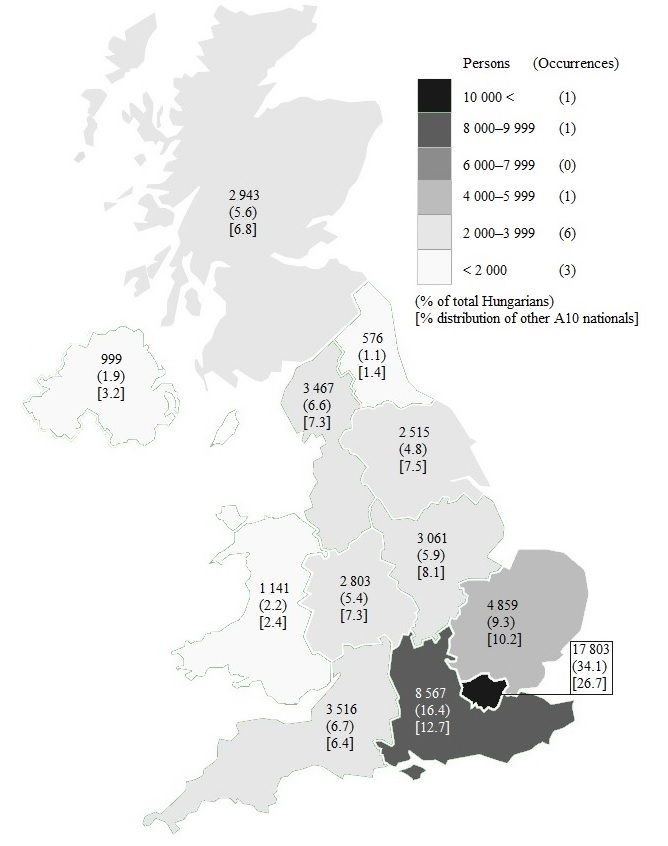

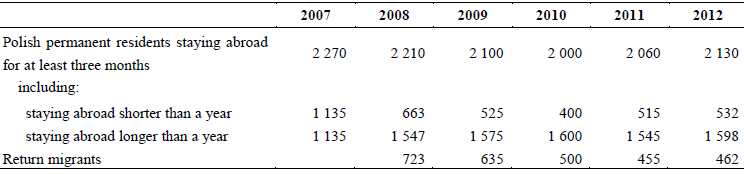

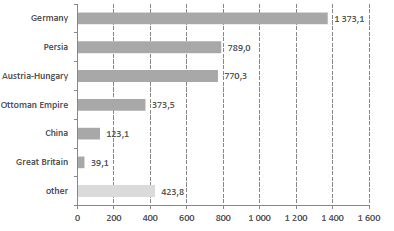

Not for long. By 1983 international mobility had begun to increase again, to reach its peak in 1989. As a result, in the years 1980-1989, Poles travelled abroad in unprecedented numbers, much more often than in any other period since the Second World War or possibly even ever during Poland’s peace-time history47 (Okólski 1994). Over one million people undertook long-term migration. Most of them settled abroad, particularly in Germany. In addition not quite a million emigrated for a period of a few months. Most of these migrations were ‘illegal’. The number of ‘legal’ migrant workers sent abroad by their Polish state enterprises increased as well. Towards the end of the period, there were almost 150 000 such workers. Finally, several hundred thousand people – if not more – undertook several million short trading trips abroad.

The increase in migration from Poland, especially long-term migration and migration for settlement, proved to be a transient phenomenon caused by the exceptional political circumstances. There is however plenty of evidence that the increase in short-term travel (or, as it was officially called, non-migration travel) was a long-term trend. Short trips abroad, which even in the late 1970s had still been hybrid in character48 evolved in time into two distinct types: tourist trips and circular labour migration.

Isolated studies of international mobility conducted in the late 1980s suggest that many households engaging in this circular migration already had migration experience and that the money earned abroad was an important part of their budgets. Those whose permanent residence was in Poland usually sold goods they had brought back with them from abroad; those who spent long periods abroad were usually employed there (Gumuła, Sowa 1990; Misiak 1988).

Many factors suggest that the increase in international mobility constituted another watershed in Poland’s modernisation story. At the beginning of the 1960s, migration from rural areas and small towns to cities, as a mass phenomenon, was finally replaced by circular movements from rural areas and small towns to cities and back; from the late 1970s onwards, the latter were in turn increasingly supplanted by growing international circularity.49 Therefore, when employment opportunities in Polish industrial centres diminished, many workers from peripheral areas might have decided to seek employment abroad or, more commonly, make some money from travelling abroad, usually without spending long time away from home.

Such a hypothesis seems justified for three reasons. First, in the migration flow from Poland which began in the 1970s, the balance between the inhabitants of highly urbanised and industrialised areas and those of peripheral regions gradually changed, as did the proportion of highly- to low-skilled workers and educated to less well-educated. Initially, migrants from cities and highly industrialised areas clearly prevailed (in absolute as well as relative terms), but their numbers gradually diminished. By the 1990s, the largest group, though not an absolute majority, came from rural regions, while unskilled migrants outnumbered skilled migrants (with at least secondary education).50

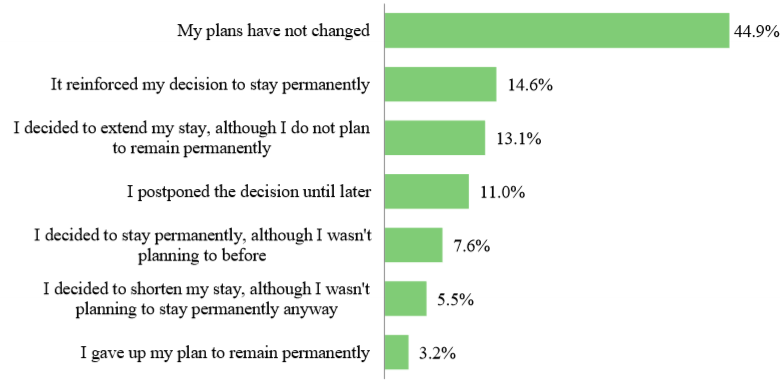

Second, the balance between those who left ‘for good’ (or at least ‘for a long time’) and those who chose a short or very short stay abroad was also reversed. At the same time, fewer people migrated as whole families (households) and more went abroad on their own, leaving their family members (or at least some of them) in Poland. In 1980-1989, at a time of mass movement abroad due to specific political circumstances, emigrants prevailed, especially those who emigrated with their whole family, even if its members did not all leave at the same time.51 This type of migration dwindled sharply in the years 1990-1993, and after 1994 it was truly insignificant in scale, comparable to the levels of the restrictive 1960s. International circularity, on the other hand, which had been already commonplace in the 1980s, intensified after 1990 and exceeded emigration for settlement by far. Unlike emigrants, short-term migrants usually travelled alone (Okólski 1994).

Third, international circular migration abroad and the migrants themselves had much in common with earlier internal temporary movements or commuting to industrial centres, and internal migrants.52

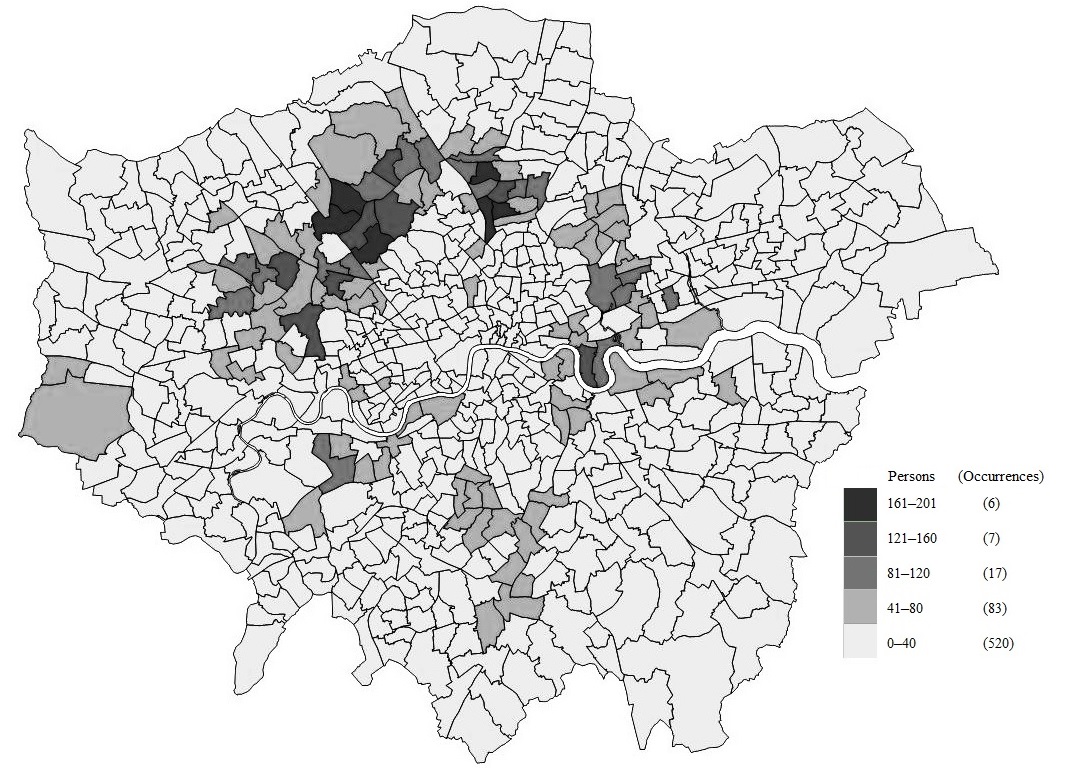

The volume of 1990s international circular labour mobility was very great. One factor contributing to its intensification at the time was the abolition of tourist visa regimes for Polish citizens in Western Europe.53 If we subtract the number of those who engaged in daily trans-border mobility, surveys conducted among travellers crossing the state border allow us to estimate the average annual size of the movements at around three million people (Institute of Tourism 1996). Furthermore, data gathered by the Centre of Migration Research in selected Polish peripheral regions suggest that approximately one in two households had some experience with migration during the period. Of these, around one-third profited from migration financially (Giza 1998).

The emergence of circular international labour migration as the most numerically significant form of mobility among Poles is undoubtedly a conspicuous demographic and sociological phenomenon. It is evidently the result of a complex set of circumstances which shaped migration in the post-war period, and in particular of the international mobility initiated in the 1970s. It is also important to note that circularity is a form of chain migration, and is fed by other international migration flows.

As stated above, the first travels abroad in search of household financial gain took place in the 1970s. The first to notice the financial potential of even a short-term trip abroad were the inhabitants of big cities, who could leave the country easily or who went abroad in connection with their jobs – state officials, scholarship holders, researchers, artists, sportspeople, employees of national commercial associations, etc. Specialists and blue-collar workers sent abroad to render ‘export services’ (especially in construction) were also able to find additional earnings. Soon, their experiences were common knowledge and people travelling with tourist groups followed in their footsteps.

The short trips, with their specialised character and their purely financial purpose, were only possible in the context of mass (and poorly regulated) trans-border movements which emerged in 1980. Afterwards, Poles travelled regularly and with increasing frequency to countries that were easily accessible to them. The basic, if not only goal of such trips, was commercial. Thus, a separate category of petty traders emerged, engaging in pendular migration. By trial and error, they found the most profitable geographical destinations, learned how to reduce transport and board and lodging costs, to overcome administrative and legal obstacles, etc. The petty traders’ methods evolved quickly: as their sales increased, they started specialising and cooperating, and instituted a division of labour; moreover, they created informal but permanent locations for their businesses, sometimes known abroad as ‘Polish markets’ (Misiak 1988; Morokvasic 1992).

At the same time, there were other categories of Polish migrant who went abroad in the 1980s. The most important of them were those who emigrated to West Germany and obtained the status of ‘expelled co-ethnic’ (Aussiedler), or those of German origin (or related to a citizen of the Federal Republic of Germany) who lived in Poland but acquired citizenship or a work permit in Germany. They created a natural migrant network which became an important channel for circular petty traders coming from Poland to access the German informal labour market (Literscy 1991; Misiak 1995).

A similar role was played by clusters of emigrants, usually part of the ‘Solidarność exodus’, who, for political reasons, had been granted temporary (usually long-term) refuge in foreign countries (Cieślińska 1997; Romaniszyn 1994; Erdmans 1998; Morawska 1999; Kurcz, Podkański 1991). They were to be found in Austria, Greece, Germany and Italy, as well as, to a lesser extent, France, Spain, the UK and Scandinavian coun tries (and even Canada and the USA). Many of the emigrants (in some cases even a great majority of them) waited there in the hope of being allowed to move to non-European immigration countries (e.g. Australia, Canada, South Africa, the USA). Before the definite move overseas, they took many jobs (sometimes legally) in the transit countries, and often found their small niches on the local labour markets. At the same time, they quickly created social centres in the receiving countries: ‘Polish’ parishes, schools, newspapers, and various services (legal, medical, etc.), and rudimentary cultural organisations. This was one of the significant factors attracting pendular traders from Poland and facilitating their temporary adaptation abroad, including finding employment. With time, the social institutions created by political refugees were completely taken over (and modified accordingly)54 by economic migrants.55

‘Polish’ niches on the informal labour market were also created in countries that did not experience a significant inflow of Polish migrants at the time. This was largely a matter of chance, though also the result of the demand for the type of job Polish pendular migrants were willing to undertake. One can thus explain the regular and relatively heavy migration flow from north-eastern Poland to Brussels or smaller flows to other countries (e.g. Iceland).

As a result, in the 1990s, petty trade related to international circular mobility, although substantially changed in character, still remained the main occupation of people from the border regions (especially the western and south-western part of Poland). The petty cross-border traders were called mrówki (Polish for ‘ants’) because of their multiple one-day-long trips to neighbouring countries with relatively small quantities of goods, no more than could be legally transported.56 The great majority of labour migrants from other regions went to work abroad. Former shuttle traders often engaged in circular labour migration or became illegal migrants (Morokvasic, de Tinguy 1993).

The unfulfilled exodus from rural to urban areas vs incomplete migration

At the present point, I would suggest that the circular movement of individual household members in search of work abroad, despite its internal diversification, can be distinguished as a specific category of international mobility and termed incomplete migration.57

One could argue that incomplete migration does not differ at all from international circularity or pendular movements, as this type of mobility is typically defined. Indeed, if we take into account the fact that definitions of circular migration primarily emphasise ‘territorial separation of obligations, activities and goods’ of circular migrants, who ‘commonly lack any declared intention of a permanent change of [their usual] residence’ (Chapman, Prothero 1985b: 1), it is easy to note its clear similarity to the international mobility of Poles (described in the previous section), but also to the earlier internal pendular movements between rural and urban areas. One significant difference, however, is that the above definition implicitly assumes58 circularity to be internal, and treats all cross-border population flows of the same character as exceptional and specific.59

What is more, it seems clear that such movements are not only typical for Poland and other Central and Eastern European countries. Moch (1997) lists many cases of international circularity of a similar nature in Western Europe at the turn of the 20th century. Inhabitants of overpopulated rural areas in less industrialised countries migrated in search of work to countries where the process of industrialisation was relatively more advanced, usually in order to find employment in construction (e.g. of roads, railways or factories). Additionally, in their two monographs, Chapman and Prothero (Chapman, Prothero 1985a; Prothero, Chapman 1985) present many contemporary examples of such migration flows in non-industrialised countries (Melanesia, Polynesia, parts of Africa and Latin America).

The trait which distinguishes incomplete migration, or the contemporary international circularity in Poland (and in other Central and Eastern European countries) is the social and economic situation of the people who participate in it, especially their exclusion, their mass and involuntary marooning at the margins of the modernisation process that the rest of their society is undergoing.

The above discussion is based on the premise that people who left Poland for a short time to earn money in the 1980s and 1990s, and those who circulated between rural and industrial areas in the 1950s, had many related or even identical characteristics. It also implies that international circularity replaced commuting as the catalyst in the process of absorption of large surpluses of labour force at the peripheries of the Polish economy. This argument, along with its tentative justification, has already been raised in the previous sections of the article.

It is well known that, in the last quarter of the 20th century, the population outflow from small towns and villages to big cities was smaller (considerably so) even than right after 1960, when it all but stopped. Therefore, the ‘migration surplus’ may have been almost impossible to eliminate. What could peasant-workers (and people in similar situations) do in the 1970s and later, when jobs that suited their situation and skills became less common? Obviously, some of them kept their jobs in the city, and some even settled there. Others, however, stayed partly idle, probably somewhat increasing their household-based self-employment.

For many reasons, the mass character of international shuttle trading after 1980 attracted such people to join in. However, they only did it because they had plenty of free time, were used to travelling and its related hardships, and not fussy about the type and conditions of the jobs they took. Study conducted by the Centre of Migration Research shows that members of these communities and households travelled abroad as petty traders or in search of temporary work as early as the 1970s (Frejka, Okólski, Sword 1998). At first, consistently with the household strategy of diversifying income, they explored the possibilities of new ways of making money. The demonstration effect, access to information and interpersonal contacts laid the foundations for future migration on a larger scale. And indeed, over the next years and decades, such migration became very popular in communities of former peasant-workers or other people in a similar situation.

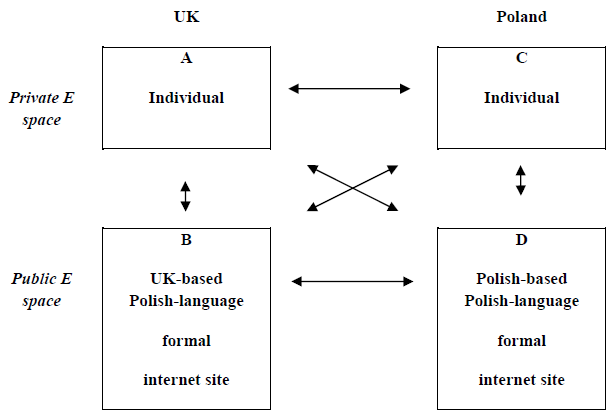

Inquiry by the Centre of Migration Research of the University of Warsaw into the phenomenon of international pendular migration by inhabitants of peripheral regions or other economically and socially marginalised Poles allow me to suggest the following description of incomplete migration.

Because of its formal status, incomplete migration is a separate and specific type of international mobility. The migrants go abroad for a short time, usually from several weeks to several months, and as a rule their stays and employment remain undocumented, as does any other economic activity they undertake. From this point of view, it is an illegal form of international circular migration. On the other hand, in some socioeconomic spaces that can broadly be described as ‘peripheral’, incomplete migration involves a large number of households, and can therefore be considered a mass phenomenon. Finally, the most important fact is that participants in this type of circularity share a number of specific traits which seem to be the result of social and economic change in the post-war Poland. The traits can be characterised as follows.

First, generally speaking, the social status of this category of migrants in Poland is rather flexible and fluid. They do not belong to any of the main strata of the emerging society; their occupational status is relatively very low; and they often do not have stable employment, are unemployed or indeed economically inactive. However, given the limited use they can make of their vocational qualifications, the value of their free time (as well as of their labour) is relatively low, which is typical in these situations. For these reasons, they are willing to travel abroad at any time it is needed or indeed possible, and to stay there for as long as they have a job or as long as their residence permit is valid. They have modest expectations concerning the conditions of employment abroad, their job and type of work, and wages, not even expecting to receive social benefits.

Second, their situation in the foreign country is rather insecure. They have no choice but to accept relatively unattractive job offers in the inferior sector of the labour market. What is more, they are employed informally, and therefore have no access to social services and – to a large extent – no legal protection in the broad sense. They often fall prey to dishonest agencies, employers and the police, and fall victim to extortion.

Third, incomplete migrants tend to fulfil the strategies of their households rather than their own individual ones. Polish households, frequently encompassing several families or generations, give moral support and financial help to the migrant, and remain the point of reference of all his or her actions and vital decisions. From the point of view of the household’s strategy, migration of one of its members is a shared investment and an enterprise similar to a joint venture whose aim is to diversify modes of income generation and to minimise risks in an unstable environment or in a situation where the social standing of the household itself is changing. This favours pendular movements between Poland and the destination country over settlement in the latter.

Fourth, the migrants exploit the fact that consumer goods in their home country are heavily subsidised by the state which gives money earned in foreign countries (after conversion to the Polish currency according to black market rate) enormously high purchasing power. It seems that sustainability of incomplete migration largely stems from the economic calculus adhered to by the migrants and based on the above-described principle.

Finally, typical of these migrants is the temporariness (usually intentional or at least conscious) of their situation and a disjointed, amorphous living pattern, in which their place of employment is situated mainly (or even completely) abroad, and their family life is centred almost exclusively in Poland (sometimes with a surrogate ‘second life’ in the foreign country), with migrants often residing in both localities. The pattern also implies a lack or a drastic atrophy of social ties and participation in public life in both places. All this contributes to the migrants’ social marginalisation in both countries and makes it permanent.

The structural characteristics of incomplete migration of Poles show its striking resemblance to the internal circularity which emerged as a result of socialist industrialisation and the related under-urbanisation. The latter, together with the transformation of internal circularity into international circularity, which we have described above, confirms the claim that incomplete migration is the result of the incomplete migration from small towns and villages to big cities.

Final remarks: the future of incomplete migration

To sum up, incomplete migration, whose emergence and evolution have a particularly complex background,60 became in the 1990s the dominant feature of the geographical mobility of the Polish population, replacing the earlier population flow to big cities and the subsequent pendular movements between peripheral localities and regional centres, or the temporary flow into such centres. The phenomenon can be defined as a trans-national circularity of people, on the one hand seeking employment and on the other enacting a household risk minimisation strategy. They move between the social peripheries of Poland and those of other, relatively more developed and richer countries. Incomplete migration is undertaken by people who are usually incapable of settling in modern economic centres of Poland (or who live at their margins) or of occupying a regular job in the mainstream economy; but also of those who know how to benefit from every occasion to make money in destination countries, even when they have to resign themselves to the situation of temporariness, undocumented status (illegality) and heightened risk. It is therefore a phenomenon which leads to increased social and economic marginalisation of the migrants in both places, in Poland and in the destination country.

Additionally, this migration is a type of spatial mobility inherited from the era of socialist under-urbanisation. It draws its strength from the conditions which are typical for a society in transition; from a deep and diverse socioeconomic imbalance within the source country and between the home country and the richer foreign destinations; from the imperfect legal regulations or inefficient application of the law in the destination country; and from the relatively unstable and amorphous social structures of the origin country.

Incomplete migration consists to a large extent in transformation of a part of local pendular movements into international circularity, and in directing the mobility away from regional centres and the national capital in the origin country towards foreign cities, and to their social and labour market peripheries in particular. The situation is apparently paradoxical, but this paradox is largely an illusion. In reality, since barriers to international spatial mobility have been largely removed, incomplete migration is oriented towards more familiar social environments with the relevant social capital and institutions, which are often more easily found in foreign rather than in Polish big cities.

On the other hand, to individual migrants this type of migration may be viewed as a survival strategy after their initial livelihoods have been become unsustainable, as a transition from passivity to an active role on the labour market. With time, the poorly skilled labour force from the Polish peripheries, initially in high demand in the nearby industrial centres, developed entrepreneurial spirit and undertook more costly and risky activities away from the home region. The change seems to have had little to do with accessing a more sophisticated quality of life. In both situations the migrating worker, instead of adapting to the cultural environment of the metropolis which employ him or her, often remains in relative isolation, bringing with him or her elements of his or her peripheral community or enhancing the provincial quality of the enclaves he or she joins in the metropolis.

Seen from a broader perspective, incomplete migration is the obvious result of the dramatic disturbances of the transition of spatial mobility, and in particular of the outflow of the surplus potential of internal circularity abroad (instead of migrating internally). Therefore, it is no coincidence that rapidly diminishing internal mobility was replaced by equally rapidly increasing international mobility. Ultimately, incomplete migration can be seen as a logical consequence of the ‘failure’ or ‘separateness’ of the process of transition of spatial mobility in relation to internal migration, especially the outflow from rural to urban areas.

Indeed, it might be argued that in the long run, many incomplete migrants will not be able to meet the challenges of the increasingly modern society and that they will not be sufficiently protected by the welfare state in their home country. On the one hand, this is the result of e.g. their low level of education and vocational qualifications; their easy-going attitudes (or indeed their lack of labour discipline); their inability to react adequately to the signals of the labour market; and, in many cases, of a protective niche created by the family home and sometimes the family business (farm, craft, trade), as well as by the support of their very strong and extended family ties. On the other hand, those people will find it ever more difficult to meet the requirements of the socioeconomic environment of the transforming origin country.

Despite all these factors and despite the implication that incomplete migration is a relatively stable, structurally based phenomenon, it can be predicted that, given the accelerating transformation of Poland into a modern market economy, it will become obsolete in a not remote future.

Notes

1 Even though the analysis in the present article concerns the situation in Poland, the observations are equally applicable to other Central and Eastern European countries. The phenomena discussed here have been analysed in a region-wide context in my earlier work (Okólski 2001c), which presents a range of evidence to argue that the phenomena are more universal than indicated in this paper.

2 According to this approach, such people should be perceived as elements of a dynamic, self-reproducing community, and therefore as a well-defined conceptual category rather than a group of individuals existing in a specific time and place.

3 However, the process was radical, far-reaching and violent in tempo. It seemed to copy the English path of development described by Karl Marx, but without ‘private capital’ and ‘exploitation’. It was also semi-autarkic, completed in international isolation. At the same time, largely because of the circumstances described above, it did not take into account the paths taken by capitalist latecomers and ignored the emergence, after the 1870s, of a structurally different type of ‘ultra-modern’ economy (at least in the economic area towards which Poland was gravitating). This required different industrial foundations (Barraclough 1967).

4 Even such influential scholars as Laslett (1965).

5 See e.g. Lampard (1969); Brown, Neuberger (1977); Węgleński (1992).

6 A long list of authors sharing this opinion can be found in Hochstadt (1999).

7 Particularly in the case of rural-urban migration.

8 See e.g. an overview of the phenomena in Moch (1997); Brown, Wardwell (1980); Champion (1989); Boyle, Halfacree (1998). A full account of the most recent research on spatial mobility in traditional or ‘pre-industrial’ societies can be found in Lucassen and Lucassen (1997). See also: Chapman, Prothero (1985a) and Prothero, Chapman (1985).

9 The list comprises three types of migration (including international migration) and two types of circulation. The types can be identified with phases of the modernisation process, are mutually complementary and, to a certain extent, interchangeable (particularly in the case of the relationship between migration and circulation). The hypothesis also states that, at the onset of modernisation, circularity was replaced by ‘unfulfilled mobility’, i.e. one which did not take place because of progress in the domain of telecommunications and transport. See: Zelinsky (1971).

10 In a way, the saturation level represents the sum of people who had migrated from rural to urban areas during the exodus.

11 The statement implies that the strength of the pull force is unlimited, which is unrealistic, though justified in the context of the ‘over-urbanisation’ thesis, rather popular at the time the described model was created.

12 However, migrants from rural areas played a significant role in re-populating many urban areas which had been de-populated towards the end of the war. For example, by the end of the 1940s they made up around 40 per cent of the inhabitants in Wrocław, 30 per cent in Łódź, and 25 per cent in Warsaw (Dyoniziak, Mikułowski-Pomorski, Pucek 1978).

13 What is more, among the mobile, the share of migrants who had only moved once increased significantly, from 43 to 70 per cent.

14 The data in this paragraph (concerning young economically active people) are taken from a survey conducted among a representative sample of the Polish population, and therefore are probably more accurate in depicting tendencies of population mobility than the data on internal migration (of the whole population) supplied by the Polish Central Statistical Office (CSO), as the former reflect actual mobility, while the latter only record residence registrations, which do not always reflect the actual scale of migration.

15 The phenomenon was probably discovered in 1967 by Stefan Golachowski, who called it semi-urbanisation. The term ‘under-urbanisation’ was suggested in 1971 by Ivan Szelenyi. See Szelenyi 1988.

16 For historical sources of the phenomenon, see Turski 1965.

17 What is more, it was believed that the best way to achieve a permanently high level of growth was to focus most investments in heavy industry, which offered opportunities for further investment expansion. Investments in the production of goods satisfying the basic needs of the population were perceived rather simplistically as a waste of the dynamic potential of the economy. The planners intended to change gradually the proportion of investments in heavy and light industry, but this was difficult to achieve in practice (partly because of a gradual militarisation of their economy and its high and growing energy consumption). This intention, like many others, was never fulfilled. The economic history of the People’s Republic of Poland (communist Poland) proves that changes to the initial strategy of economic development, whose cornerstone was socialist industrialisation, were largely the result of social pressure, rather than intentional adjustment of fundamental principles.

18 In the economic literature, the phenomenon is called, rather picturesquely, labour hoarding.

19 In many Western countries, at the peak of the industrialisation process, there were also many industrial workers employed away from their place of residence. However, they were usually seasonal workers, relatively redundant in their native rural areas, and they did not commute daily, but rather lodged in makeshift conditions close to their workplace (e.g. Hochstadt 1999). Such a transitional status of rural migrants in search of employment in cities was ephemeral in comparison with the mass phenomenon.

20 To prove that the non-local labour force was relatively cheap, we do not even have to demonstrate that in reality the wages of non-local workers were lower than those of local employees, though, given e.g. the jobs, the level of education and qualifications of the former, such a situation was relatively frequent. Even if the planners (in the role of collective employer) had kept the average pay at the same level in both groups, it would have satisfied only the basic needs of the non-local workers, and would not have been sufficient for those living locally. To balance this disproportion, indirect subsidies were offered e.g. to help rent and maintain a flat, buy food, pay energy bills, etc., which was more useful to locals. A similar picture emerges from the results of empirical studies (Nasiłowski 1958).

21 The relatively lower aggregate demand of households makes it easier to choose the rate of accumulation and the structure of investments, which in turn results in a more dynamic investment process and helps accomplish projects which drive production forward.

22 Some also point out the following advantages of living outside industrial centres and working in them: healthier natural environment, safety, bigger houses, closer family ties, especially in families with small children, generally healthier living conditions, etc. (George 1968; Wiles 1974). Personally, I am not convinced of the significance of these advantages.

23 Of course, what I mean is the circumstances following the post-war mass displacements of the population and the settlement of the abandoned cities.

24 To make them more efficient (although also for other reasons), in the first half of the 1950s, newcomers were not allowed to settle in some cities.